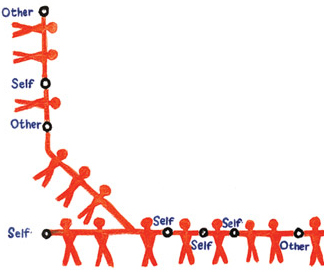

This is a good example of bad public art. It’s not new—it’s from 2011—but the design is still printed onto seats on the Tube in London, and I found myself staring at it the other day with appalled fascination. It’s called Acts of Kindness, by Michael Landy, and the public were meant to go to a website to share stories of people being nice to one another. What’s wrong with that?

Almost everything.

One thing to notice is that the figures are all adult men: they have broad shoulders and narrow hips. Presumably the artist wanted to be inclusive, yet it didn’t occur to him to draw a gender-neutral figure, or a mix of men, women and children.

And what does the image mean?

Self? Other? Who talks that way? No one. The natural word choice would have been me and you—but that would have sounded cute and childlike, and exposed the vapid sentiments for what they are. ‘Be nice.’ It is insincere, trite and patronising.

If I see someone in need on public transport I do my best to help. I do it without thinking—and I wouldn’t write in to a website about it. It’s normal life.

The red line and white circles of the design echo the Tube map. A train just gets you from A to B. It doesn’t love you. It doesn’t care. It isn’t kind. It is a machine. So here, human interaction is explicitly likened to the workings of a machine. We are being instructed to care (as if we don’t) and at the same time told that we are cogs in a machine.

So the chosen visual metaphor stands in direct contradiction to the core message.

The blank faces of the figures further underline the mechanistic imagery. Why not use smiley faces? Again, that would have showed up how empty the whole thing is.

Of course, it’s not difficult to give a simple smiley face real humanity and warmth. A 4yr old can do it. But commissioning a conceptual artist like Michael Landy gives the project the whiff of high seriousness, as if the act of stepping outside of oneself is some great existential drama. For normal people it’s really not that difficult.

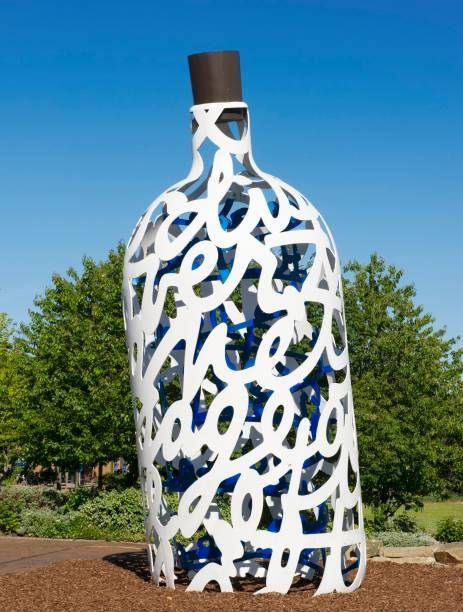

One of the first of the new generation of public art commissions in the UK was in Middlesbrough in the 1990’s. Claes Oldenburg’s ‘Bottle of Notes’ is a giant metal bottle formed from handwriting taken from Captain Cook’s journal. (Captain Cook was a local boy.)

Much of Middlesbrough is bleak, post-industrial wasteland – made worse by the deliberate destruction of so much of the19th Century architecture.

The artwork was meant to cheer people up. But who sends a message in a bottle? Someone marooned, desperate to escape, who has no other options left. Someone living in Middlesbrough.

The traditional features of a monument: symmetry, ornament, order, sobriety, create the sense of a place as a centre, somewhere worth belonging to. It is an invitation to settle, to put down roots, to stay and add your own story to the history of the place.

Old monuments had meanings that are now forgotten. A simple obelisk or standing stone was a representation of the cosmic centre, a marker of soaring aspiration, saying that this particular, specific spot could be the centre of the Universe, the omphalos, the ‘navel of the world’.

Any homemaker attempts to cast the same kind of magic spell – to create a home is to make even the most ordinary house seem like the very centre of the Universe, the very best place on Earth. A somewhere that you wouldn’t willingly swap for another.

The moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt (an atheist) defines the sacred as whatever we hold to be of ‘infinite value’. To make a home is to confer infinite value on a particular, specific spot on the Earth’s surface, to make a sacred space.

The omphalos, the magic centre, was where the gods spoke to humankind, where it was suddenly possible to transcend everyday realities. And every home is the scene of transcendent moments, rites of passage that are of infinite significance and meaning—a first word, a first step, a first kiss. Birth, sex and death.

Visual symbolism, when first developed, wasn’t bland, functional information graphics. Symbolism evolved as our ancestors tried to evoke a sense of the transcendent, to mark things, people, places as special, uniquely valued.

Each art tradition was a visual language of coded, layered meaning.

You can read the elements of Classical decoration as a language intended to conjure both fertility and order at the same place at the same time: Dionysian excess in tension with Apollonian restraint. Swirls and volutes, vine leaves and centaurs, contained within serene geometry.

The Medieval ornament of a cathedral is number magic – the number three is deeply significant in Christianity – but it is left to the viewer whether they see the Trinity in every triangle and trefoil.

The purpose of ornament escapes easy definition precisely because it is a language of layered meanings. You are free to enjoy the surface only, but the surface is only so attractive because of the depth beneath. And even if we don’t speak the language, we still sense the presence of a genuine system of meaning.

The iconoclasm of the 20th century did away with visual symbolism. Adolf Loos said ‘ornament is crime’. Modernism claimed to care only for function, utility—so a house was ‘a machine for living in’.

But pattern-making, symbolism and ornament perform a profound spiritual function.

Monuments have spiritual uses and answer spiritual needs. The only way to make where we live a better place is to tell ourselves that there’s nowhere we’d rather be: that this particular spot really is the very best place on earth.

Captain Cook’s story, Middlesbrough’s story, could be genuinely celebrated—the man and the city played a pivotal role in world history. Captain Cook was a courageous explorer, and a much—loved leader figure, who can’t be blamed for the sins of later colonists. Middlesbrough was one of those boom towns of the 19th century that made the modern world. Sydney Harbour Bridge is made with Middlesbrough steel.

But Claes Oldenburg likes to clown around. He doesn’t do nobility or heroism. He can’t be seen to take anything seriously. The Bottle of Notes is made to look as if it accidentally fell into place, or just washed up there. The asymmetry—the unsettledness—says that this place is no more special than any other, that its value is doubtful. And the loopy writing has been stripped of meaning and rendered illegible—a chaotic scrawl, a mass of scribble.

Plonking a monument to meaninglessness in the middle of a troubled town helps no one—least of all those ordinary people struggling to cultivate a new sense of purpose, struggling to make a better place and better lives for themselves.

More dramatically off-centre is Oldenburg’s ‘Dropped Cone’. Perched precariously on the corner of a building in Cologne it echoes the spires of the nearby Cathedral, mocking the whole idea of centredness.

The Italian thinker Augusto Del Noce said that “Modernism aims at the elimination of transcendence.” A cathedral spire, pointing to the Beyond, says that there are transcendent realities, mysteries we should honour, rather than shrink to fit our limited brains. Eric Voegelin said that we all live caught between the finite and the infinite, between what we can know, and what is forever unknowable—forever out of reach. Pointing toward the unattainable, a spire embodies humility and aspiration at once.

But the Dropped Cone aims to eliminate transcendence. It says that the nearest we’ll ever get to the infinite is a cheap ice cream—and then, like clumsy children, we’ll probably drop it anyway—or throw it away. A dropped ice cream is an image of careless, trashy consumerism, a society where our material needs are sated, glutted, but where spiritual needs are not just denied, but ridiculed.

Of course the two go together—they are two sides of the same coin. To treat the material world as trash, you also have to trash spirituality. But I don’t think it was meant to work out like this. I think people assumed that once our material needs were met, we’d have leisure to make beautiful things not just stupid jokes.

Great cultures of the past were built around grand unifying ideas.

Each culture had its own language of pattern and visual symbolism, its sacred stories, its own way of marking the infinite value of a particular, specific place.

Each culture had its own conception of beauty, and that particular vision of beauty was precisely what defined the culture and brought people together—whether in Ancient Greece, Medieval Europe, or Mughal India.

In the 20th century the old culture of Europe died and nothing coherent has been born to take its place. The iconoclasts did a thorough job. We have no shared, unifying idea of beauty, and public art only highlights that confusion and emptiness.

As a society we agree on the rights of the individual, we agree on the need for tolerance, diversity, equality and freedom, and of course those are important virtues, but they are centrifugal not centripetal. They are virtues of difference and dispersal, not oneness or coherence.

They give us nothing to gather around, no central point of orientation. No way of saying: this is special, this is sacred, this, to us, is of infinite value. If the only remaining sacred principles are the rights of the individual, then society is ever more atomized. Self. Other.