Science / Tech

Is Sex a Dirty Word?

Within the lens of Western culture, it is sex and not money that is the primary root of all evil.

In Birka, Sweden, Viking bones from grave B581 until recently were categorized as “anomalous” where “…the gender of the skeleton appeared at odds with the martial objects buried with it.” (emphasis added).5,12 Contemporaneously, in Lewes, East Sussex, England, the Priory school has ordered girls to don trousers in order to make the school uniform gender neutral. Piers Morgan, prominent UK TV figure, and Priory school sixth form “Old Boy,” has said, “Let boys be boys and girls be girls, and stop confusing them in this ridiculous way.”30 Commenting upon gendered language, Arwa Mahdawi stated, “We are more aware of the problems of gendered language than ever and, as the use of the singular they demonstrates, we are taking steps to fix it. At the same time, however, we seem to be creating a gendering of language as the popularity of words such as mansplain and girlboss demonstrate.”19 The term “gender” is misapplied, gender neutrality questioned, and “gendered language” on the rise.

So what does all of this have to do with sex?

This paper will focus upon the use of the term “gender” itself in the arenas of popular culture and science, as a follow-up to Haig11 and McConkey.18 Beginning with a focus on the conceptual drift in the meaning of the term, and how this reflects social and political influences that obscure biological sex differences and raise the potential for serious unintended consequences. A second concern is peoples’ (including many scientists’) beliefs about the causal factors underlying sexual differences. The transmutation of sexually dimorphic qualities into gender differences has been a sleight of hand that moves the focus to purported social influences on these differences, when in fact, the empirical evidence for these influences is often weak or in conflict with what has been observed.

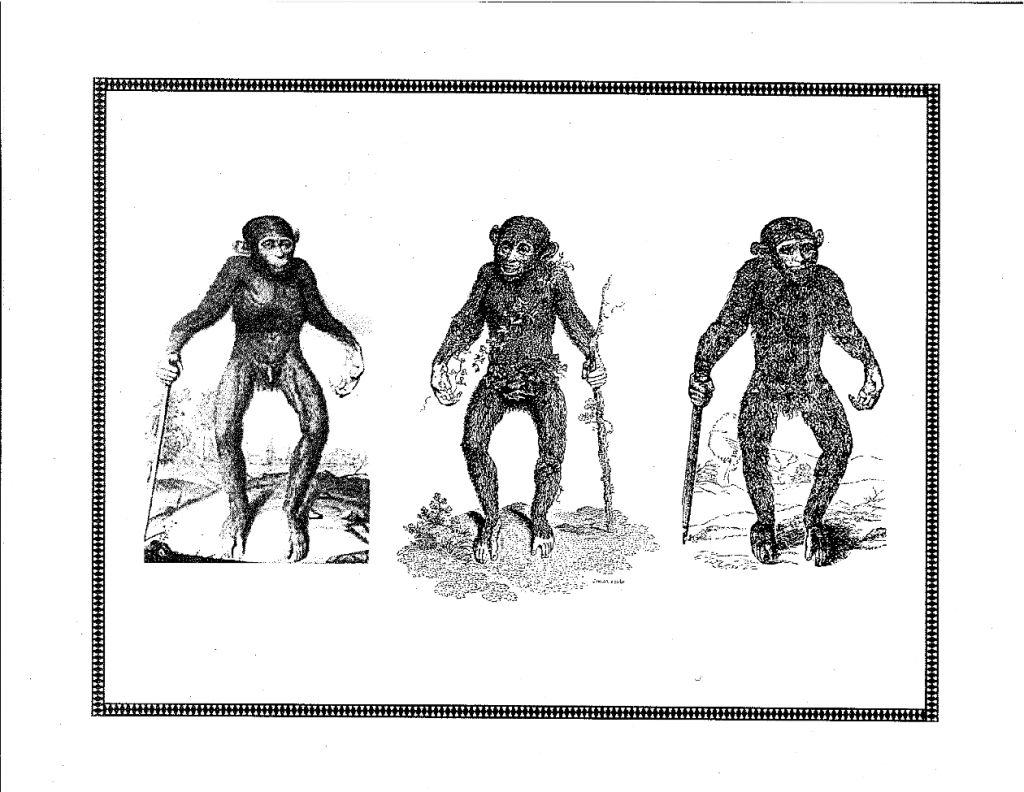

The obscuring of issues related to sex is not new and is perhaps understandable, even if not always desirable. Within the lens of Western culture, it is sex and not money that is the primary root of all evil. It is arguably the primary generator of conflict between and within the sexes, and social mores and legal sanctions (for example laws against polygamy) have emerged to quell these conflicts. These mores and legal sanctions can, however, overshoot their target and do so in ways that impede scientific progress and suppress open discussion of sex and sex differences. As an example, let’s step back a few centuries to 1699 and Edward Tyson’s seminal work in comparative anatomy. His associated book included a figure that accurately represented the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), including the male’s genitalia, shown as the leftmost illustration in Figure 1.28 It is unabashedly clear that the chimpanzee has a well-developed penis and scrotum (good for them!):

One hundred years later, Tyson’s chimpanzee reemerged in George Shaw’s General Zoology, or Systematic History, but now with generous coverage of obscuring ivy (middle illustration in Figure 1).25 Still later, in 1863, Thomas Huxley, at the time one of Charles Darwin’s strongest advocates, published his volume Evidence for Man’s Place in Nature.16 Huxley presents an illustration which he states is reduced from Tyson’s. Although it is a fairly good facsimile, the preeminence of the animal’s genitalia is greatly reduced, if not almost obscured. It would certainly have been possible for Huxley to present Tyson’s original figures with great accuracy and appropriate detail, but he chose not to. It appears that even an individual of Huxley’s prominence was subject to the social pressures of the time. Very simply put, this example illustrates that sex is a potential hot button issue and research on the topic of sex has been subject to social pressures that channel discussion in ways that make it more socially palatable, but at times at the expense of scientific accuracy.

We believe this is continuing to this day, with ‘gender’ becoming the obscuring ivy of ‘sex’, as aptly discussed by David Haig.11 According to the Oxford English Dictionary the term “gender” is from the Anglo-Norman and Middle French, referring to “kind; sort; sex; quality of being male or female; race; people”; and (in grammar) class of nouns and pronouns distinguished by different inflections. Up until the early 1970s, gender was most commonly associated with the field of linguistics, and was routinely applied in works on language analysis. There are languages without grammatical genders; there are others that recognize masculine and feminine, and still others that add categories of common and neuter. There are even a few languages that employ more than three grammatical genders (i.e., Chechen with 6 and Shona with 20 noun classes). In any case, the term gender began to take on wider meaning in the mid-1950’s with John Money’s early work on the psychological and social development of individuals with ambiguous genitalia,20 and later with his and Anke Ehrhardt’s Man & Woman, Boy & Girl: The Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity.21 According to the authors:

[O]ne goal of the book is to organize old and new knowledge into a theoretical formulation of the behavioral dimorphism and differentiation of male and female into a theory not simply of psychosexual development but also of psychosexual human sexual behavior more comprehensively than is done by traditional developmental theories of masculinity and femininity (Money & Ehrhardt, 1972, p. ix).

Money and Ehrhardt began with a presentation of the genetics of human sex determination, with a flowchart that presents appropriate milestones in sexual development. Two terms receive particular attention thereafter. The first, “gender role,” was used by Money and intended to cover “all those things that a person says or does to disclose himself or herself as having the status of a boy or man, girl or woman respectively” (p. 254).20 The second term, “gender identity,” is described as “the sameness, unity, and persistence of one’s individuality as male, female, or ambivalent, in greater or lesser degree, especially as it is experienced in self-awareness and behavior; gender identity is the private experience of gender role, and gender role is the public expression of gender identity” (p. 4).21 Additionally, the authors make reference to sexually dimorphic behaviors and elaborate:

The central nervous system, in so far as prenatal hormonal factors made it sexually dimorphic, passes on its program in the form of behavioral traits which influence other people, and which are traditionally and culturally classified as predominantly boyish or girlish. These traits do not automatically determine the dimorphism of gender identity, but they exert some influence on the ultimate pattern of gender identity, for instance in tomboyish feminine identity in girls, and its opposite in boys. The predominant part of gender-identity differentiation receives its program by way of social transmission from those responsible for the reconfirmation of the sex of assignment in the daily practices of rearing. Once differentiated gender identity receives further confirmation from the hormonal changes of puberty, or lack of confirmation in instances of incongruous identity. (p. 4).21

It is fairly clear that Money and Ehrhardt recognized individuals as having a sex and believed that their biological base, including their gender-identity and social behavior (gender role), is influenced (though not necessarily fully determined) by social experiences; gender is a socially prescribed “role” and is acquired through experience. “Gender” is not present prenatally, and it is therefore not the same as “sex” which can be ascribed to an individual in utero. Money and Ehrhardt combined “gender” with the terms “identity” and “role.” The term “gender” itself did not appear as an individual concept in their glossary, but a Google search reveals its use on some 1,060,000,000 websites, and Haig demonstrates it rise in the social sciences, humanities, and natural sciences since the early 1980s.11 This gender diaspora may in part be due to the now common replacement of “gender” for “sex”,13 but this is not the full story. There is pervasive confusion among the general public, including most journalists, and among many scholars. The common use of the term gender identity and gender role not only deviates from the original definitions it is also based on the incorrect belief that they are as strongly influenced by social experiences as proposed by Money and Ehrhardt.20,21 We’ll have more to say on this later, but let’s first indulge in some of the confusion.

Consider first a December 2012 newspaper article: “Rooneys reveal baby’s gender.” In the body of the article, it was stated “the soccer star and his wife revealed the news after having a scan confirming the sex of the child”10. Perhaps the revelation that the “gender” of a fetus – a substantial drift from Money and Ehrhardt’s initial differentiation of sex and gender – could be determined is not that surprising. The uncritical social acceptance of the impossibility of knowing a fetus’ gender, per Money and Ehrhardt’s original definition, is the basis for the current “gender-reveal” phenomenon. These popular celebrations are elaborately planned and executed, with themes such as: prince or princess; lashes or mustaches; boots or bows; touchdowns or tutus; rifles or ruffles.

The highlight of the soiree is the “moment of reveal” which could include confetti falling from a box; smoke bombs; cake cuttings; helium balloons floating out of a box when opened and so on. This over-the-top and inappropriate gendering of the fetus and in some cases newborns is now being foisted upon other species, albeit we suspect they are rather indifferent to their assigned gender.

In September 2013, the Manchester Guardian reported the following: “U.S. National Zoo’s surviving giant panda cub is a ‘healthy and vibrant’ girl—Pandering to popular request, officials have released gender and health tests results for the zoo’s unnamed panda cub”.14 In the body of the article, it was again reported that “scientists conducted two tests to confirm the gender of the cubs. A DNA test was required to determine the cubs’ sex because bears don’t develop external genitalia until they have aged several months”. So, what was sex, per Money and Ehrhardt, is now gender and what was gender as applied (inaccurately, as we discuss below) to human development is now extended to other species, even those we presume do not have the self-and social-awareness needed to have a personal gender identity. It could be that the use of gender instead of sex in these cases results from reporters’ lack of familiarity with the scientific literature, or scientific illiteracy resulting from the more general obscuring of “sex” by “gender”, as David Haig documented following the rise of feminism. But, the loose use of gender has also made its way into scientific reporting.

One example comes from a 2013 Discover article on prenatal sex ratios, “When do girls rule the womb? Social factors can’t explain shifts in human gender ratios, its [sic] time to ask evolutionary biologists for help”.1 In the body of the article, the following statements are made: 1) “The researchers found no socioeconomic link to fetal gender;” 2) “And the sex ratio decline in the West, where the proportions of boys to girls moves closer to 1-to-1, might be explained by improved life expectancies reducing the gender difference in mortality in some regions”. Even though this is a science-oriented magazine, it is intended for a general readership, and the naivety defense might again be invoked.

In contrast, Nature is a well-respected scientific journal and platform for scientific discussion that should be of interest to the informed public. It carries a reputation that would suggest careful editorial scrutiny; however, in March 2014, an article by Linda Schiebinger focused on a very relevant health issue for the public.23 The bylined article was “Scientific record must take gender into account—from car design to drug discovery, the failure to acknowledge sex differences can be costly and even lethal, argues Londa Schiebinger.” In her important piece, the following is reported: “including gender analysis in research can save us from life-threatening errors…and can lead to new discoveries. Gender analysis has led to better treatments for heart disease in women. Identifying the genetic mechanisms of ovarian determination has enhanced knowledge about testis development” (p. 9).23 It may be that “gender analysis” has come to be the accepted descriptive vocabulary for tests intended to examine whether “sex” is a critical variable in the proposed examinations; if it is, it shouldn’t be. The medical issues discussed in her article are biologically related and not the result of a gender identification or adherence to a gender role.

As just one example of this definition creep into the scientific literature, consider “Forensic Identification of Gender from Fingerprints” published in 2015 in Analytic Chemistry.15 In the abstract, it is asserted: “In our approach, the content present in the sweat left behind—namely the amino acids—can be used to determine physical such as gender of the originator.[sic]” (p. 11531). In two of the four figures in the paper, the captions refer to the two sexes, “male” and “female.” In a third, the sample is all “female” and in the only table, values of amino acids are presented in two columns labeled as “female” and “male.” The discordance between the abstract and the paper is unfortunate, but perhaps acceptable, since fingerprints are not impacted by the potential “gender classification” they might be given.

The final and to us most disturbing example occurred in Child Development, one of the preeminent journals in developmental psychology; ”Gender Development in Transgendered Preschool Children”.8 The opening sentence in the abstract accurately states: “an increasing number of transgender children—those who express a gender identity that is ‘opposite’ their natal sex—are socially transitioning, or presenting as their gender identity in everyday life” (p. 1). Later, however, the abstract closes with “…transgender children were less likely than both control groups to believe that their gender at birth matches their current gender, whereas both transgender children and siblings were less likely than controls to believe that other people’s gender is stable.” It is unlikely that the subjects of the study had a gender at birth, although they may have been assigned a natal sex.

In any event, let’s return to Money and Ehrhardt. When their book was published there was very little in the way of clinical work on intersex. An unfortunate experiment of nature came John Money’s way in David Reimer.6 Reimer was one of a set of twin boys, Bruce and Brian, born to Ron and Janet Reimer. At the time of a neonatal circumcision an accident with the electric cautery left David (the name which was eventually taken on by Bruce) with only remnants of a normal penis. David was taken to Johns Hopkins and entered as a patient in their Psychohormonal Research Unit. He received reconstructive surgery and Money took over case management. As noted earlier, Money believed that individuals were born with the potential to develop as either “male” or “female” depending upon the individual’s anatomy and rearing. Money believed that David, a normal genetic male, who had been reconstructed as a female could successfully transition to a female, if raised accordingly. At the time, Money would not have had the advantage of the now considerable knowledge of the effects of prenatal exposure to hormones on brain and behavior, although there was emerging evidence for these effects in the scientific literature.32 Regardless, Money proceeded to follow-up on David’s progress. According to Colapinto6:

That Money recognized the very special place that Brenda [Bruce’s post sex reassignment moniker] Reimer’s case occupied in his work—and indeed within the entire history of sex research—was clear from the emphasis he gave it in Man & Woman, Boy & Girl. First mentioned in the book’s Introduction, it was then cited at various key points throughout the text; in Chapter 8 on Gender Identity Differentiation, in Chapter 9 on Developmental Differentiation, in Chapter 10 on Pubertal Hormones. It was in Chapter 7, on Gender Dimorphism in Assignment and Rearing, that Money explored the case at greatest length, his account having been assembled from first-hand observations of Brenda during the family’s annual visit to his Psychohormonal Research Unit, and from letters and phone calls with Janet during the year (p. 68).

Money suggested that the negative gender role and gender identity issues that might have been predicted were not evident and that because of gender neutrality at birth it is possible to channel an individual into either of the two gender categories. This all would have become routine intersex case management, according to the “Hopkins protocols,” as the five publications by Hampson and Hampson appearing between 1955 and 1956 in the Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, came to be called,7 had it been the real situation. The snag was that Money was not accurately presenting the post-operative development of David Reimer. The accurate situation was that David rejected his female role identity and actively attempted to assert his masculine identity. As well presented in John Colapinto’s book,6 David experienced great unhappiness and instability; eventually he had a second reconstructive surgery to masculinize his genitals, and at that point moved from the name Brenda to the name David. Although uncommon, there are similar cases whereby the gender identity is consistent with the individuals’ birth sex and not the sex or gender of rearing.2 One example is Reiner’s and Gearhart’s study of biological males (with male-typical prenatal exposure to testosterone) who were raised as girls due to pelvic birth defects.22 Among other things, all of these children reported male-typical play and interests (e.g., wrestling, ice hockey) and none of them reported much engagement in female-typical play (e.g., dolls). Eight of 14 children who were raised as females, eventually changed to a male identify; five retained a female identity and the other refused to discuss it.

We see a similar disconnect between beliefs about gender roles and actual sex-typed behavior with the comparison of children raised in gender-egalitarian households to those raised in traditional households. Children in the former, especially girls, had less sex-typed beliefs about future occupations and preferences than other children, but their actual play and social behavior was no different than that of children raised with more traditional beliefs. So, children’s explicit descriptions of sex roles were influenced to some extent by their parents, but they behaved in sex-typical ways independent of their parents’ parenting style and gender-equality beliefs.31

These studies and the well-known prenatal and post-natal influence of sex hormones on many things (e.g., play behavior and sexual orientation) – in people and other species – now attributed to socially-imposed gender-identity and gender-roles give us reason to pause and to more carefully consider a casual acceptance of the incorrect usage both of the word “sex” and “gender”.3, 29 These words carry specific meanings and their appropriate usages in the scientific and lay literatures will not only add precision to the accumulating research corpus on sex differences, it will also reduce the apparent widespread confusion among the general public. The conflation of sex and gender is sometimes driven by naiveté. At other times, it is driven by self-interested distortions that follow the post-modern edicts of a socially constructed reality and the belief that there are no real differences between people (including the sexes) that aren’t imposed on them and that cannot be corrected by some form of social engineering.13 This is not simply an academic debate, as the obscuring of sex by gender has led to the failure to acknowledge – and sometimes a willful denial – that people’s ‘gender identity’ and ‘gender role’ behavior is not subject to personal disposition or faddish pursuit that in turn creates a real potential for unintended consequences.

This ongoing and wide spread deconstruction of gender is nicely discussed by McConkey,18 and Soderlund and Madison.26 Ironically, one area in which this is being played out is with children with gender dysphoria and when and how they might transition (see also this piece from Jesse Singal). According to Debra W. Soh:27 “Distortion of science hinders progress. When gender feminists start refuting basic biology people stop listening, and the larger point about equality is lost.” And

…ignoring the science around desistance has serious consequences; it seems some transgendered children will needlessly undergo biomedical interventions, such as hormone treatments. Even detransitioning from a purely social transition can be a difficult process for a child. In one 2011 study of 25 gender dysphoric children, 11 desisted. Of the desisters, two had socially transitioned and regretted it. They struggled to return to their birth sex in part because of fear of teasing from their classmates, and they did not dare to make the change until they enrolled in high school.

Soh closes her op-ed as follows:

Both the gender feminists and transgender movements are operating with good intentions—namely, the desire to obtain the dignity women and transgender people rightly deserve. But it’s never a good idea to dismiss scientific nuances in the name of a compelling argument or an honorable cause. We must allow science to speak for itself.

In the context of the social climate, the attendant obscuring of biological influences on sex differences, including gender identity and gender roles, has contributed to a massive increase in referrals to gender identity clinics in England.17

It may well be that there are more gender dysmorphic children than previously thought and more of them coming to these clinics as social mores change, but the actual roots of this increase are unclear at this point2. Of particular concern are the radical steps being put forward in Great Britain, where the current medical and psychological processes are proposed to be streamlined. This time-saving effort would involve: 1) the eliminating of a formal medical diagnosis, and 2) foregoing the present two-year-plus pause period during which the individual lives as their acquired gender identity. It appears the goal is to make it possible for someone to medically “transition” via hormonal treatment, by simply self-identifying as their preferred gender. It seems that identity “gender” trumps biological “sex.”

These are complex, socially critical issues that are not yet fully understood. Conflating sex and gender and putting this conflation into medical practice could result in a spate of disastrous cases.

The uptick in the use of gender in place of sex was pushed by some feminists who argued that gender reflected social influences, following Money, but then taking it one step too far by often concluding that all (or nearly all) psychological and social sex differences were caused by social and experiential factors, not by biology. By this account, what were once considered sex differences are now “more accurately” described as gender differences. This is a step too far because the evidence that the many documented sex differences are actually caused by social factors is much weaker than one might conclude by the widespread use and apparent acceptance of “gender differences”. To be sure, there are social (for example the ratio of marriage age men and women) and cultural (such as socially imposed monogamy) influences on the expression of many sex differences. However, it does not follow that these differences are caused by these social factors, only that the expression of core differences (such as the desire for multiple mates) are modified by contextual factors, as is the case in other animals.

Moreover, many presumed social causes of sex differences may actually reflect emergent dynamics of boys’ and girls’ and men’s and women’s biologically-based behaviors. By analogy, Adam Smith’s invisible hand is not a causal mechanism, but rather a description of the economic dynamics that emerge from the self-interested activity of individuals within free markets. Gender roles are much like the invisible hand. They are descriptions of behavioral and psychological sex differences that emerge when individuals are not ecologically or socially constrained, which is why many sex differences actually become larger in wealthy democratic nations with mores of gender equality.24 For instance, sex differences in early play behavior (e.g., with dolls versus guns) are very large, well-documented, and influenced by prenatal exposure to male hormones. But these differences are thought by many to be caused by socialization and stereotypes, and part of the developmental funnelling of boys and girls into ‘appropriate’ gender roles. The Swedish government in fact determined as much, by fiat it seems, and is now intervening with teachers and children to abolish these stereotyped gender roles and associated sex differences.4

Adults can certainly change the play behavior of children, but not without an explicit and protracted intervention. It’s akin to walking upstream. You can certainly do it with enough effort, but once this effort stops, you flow back downstream. Our point here is that in the absence of sustained intervention, boys and girls will create for themselves social and play scenarios that have a biological basis to them, and the “causal mechanisms” of stereotypes and socialization are largely description of these emergent features of children’s social development.9 We’re not arguing that there are no social influences on these, but that they have been over-estimated and biological influences under-estimated. If we’re correct, the Swedish efforts will eventually come to nothing, other than stressed out teachers and children.

For now, the general public might be better served if scientists and serious scholars pointed out that the conflation of sex and gender is more strongly driven by the social and political mores of the times than by scientific evidence regarding the causes of sex differences. And that such conflation has probably delayed the scientific study of sex differences, not only for behavior but also as related to disease risk and treatment, by decades. The social obscuring of sex differences may meet the personal and political goals of some individuals, but this may come at a cost to many others.

References

1. Abbasi, J. (2013). When do girls rule the womb? Oct. 2013.

2. Bailey, J. M.; Vasey, P. L., Diamond, L. M.; Breedlove, S. M.; Vilain, E. & Epprecht, M. (2016). Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 17, 45-101.

3. Baum, M. & Bakker, J. (2017). Reconsidering prenatal hormonal influence on human sexual orientation: lessons from animal research. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 46, 1601-1605.

4. Bayne, E. (2009). Gender pedagogy in Swedish pre-schools: An overview. Gender Issues, 26, 130-140.

5. Cocozza, P. (2017). Does new DNA evidence prove that there were female Viking warlords? The Manchester Guardian, 12 September 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/science/shortcuts/2017/Sep/12/2017/does-new-dna-evidence-prove-that-there-were-female-Viking-warlords

6. Colapinto, J. 2000. As Nature Made Him—the Boy Who Was Raised As a Girl. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

7. Eder, S. (n.d.) The Birth of Gender: Medicine and the Transformation of Sex in the 1900s. Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. https://www.mping-berlin.mpg.de/en/research/projects/DeptII_Eder_BirthofGender

8. Fast, A. A. & Olson, K. R. (2017). Gender development in transgender preschool children. Child Development 1-18. DOI 10.1111/cdev.12758

9. Geary, D. C. (2010). Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences (second ed). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

10. Gordon, B. (2012). ‘Gender-reveal’ cakes. Sorry but this is one baby celebration too far. Daily Telegraph, May 1, 2012. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/mother-tongue/9236463/Gender-reveal-cakes-sorry-but-this-is-one-baby-celebration-too-far.html

11. Haig, D. (2004). The inexorable rise of gender and the decline of sex: Social change in academic titles, 1945–2001. Archives of sexual behavior, 33(2), 87-96.

12. Hedenstierna-Jonson, C.; Kjellstrom, A.; Zachrissson, T.; Krzewinska, M.; Sobrado, U.; Price, N.; Gunther, T.; Jakobsson, M.; Gotherstrom, A.; Stora, J. (2017). A female Viking warrior confirmed by genomics. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2017 1-8.

13. Hicks, S. R. (2004). Explaining postmodernism: Skepticism and socialism from Rousseau to Foucault. Scholarly Publishing, Inc.

14. Holpuch, A. (2013). US National Zoo’s surviving giant panda cub is a ‘healthy and vibrant’ girl. The guardian.com, Thursday 5 September.

15. Huynh, C.; Brunelle, E.; Halankova, J.; Agudelo, J. & Halamek, J. (2015). Forensic identification of gender from fingerprints, Analytic Chemistry 87: 11531-11536.

16. Huxley, T.H., (1863 Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature, London: Williams and Norgate.

17. Lyons, K. (2016) Gender Identity clinics services under strain as referral rates soar. The Manchester Guardian, July 2016.

18. McConkey, M. (2017). Why we should stop using the term (Gender). May, 2017.

19. Mahdawi, A. (2017). Allow me to womansplain the problem with gendered language. The Manchester Guardian, April 23, 2017.

20. Money, J. (1955). Hermaphroditism, gender and precocity in hyperadrenocorticism: Psychologic findings. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, 96(6), 253-264.

21. Money, J. & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & Woman, Boy & Girl: Differentiation and Dimorphism of Gender Identity from Conception to Maturity. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press.

22. Reiner, W. G., & Gearhart, J. P. (2004). Discordant sexual identity in some genetic males with cloacal exstrophy assigned to female sex at birth. New England Journal of Medicine, 350, 333-341.

23. Schiebinger, L. (2014). Scientific research must take gender into account—from car design to drug discovery, the failure to acknowledge sex differences can be costly and even lethal. Nature, 507:9

24. Schmitt, D.P. (2015). The evolution of culturally-variable sex differences. Men and women are not always different, but when they are…It appears not to result from patriarchy or sex role socialization. In T.K. Shackelford & R.D. Hansen (Eds), The evolution of sexuality (221-256). London: Springer.

25. Shaw, G. (1800). General Zoology, or Systematic History. London: Kearsley.

26. Soderlund, T. & Madison, G. (2017). Objectivity and realms of explanation in academic journal articles concerning sex/gender: a comparison of gender studies and other social sciences. Scientometrics. DOI 10.1007/SH192-017-2407-X

27. Soh, D. W. (2017). Are gender feminists and transgender activists undermining science? LA Times, February 2017.

28. Tyson, Edward (1699). Orang-Outang, sive Homo Sylvestris: or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie Compared with that of a Monkey, an Ape, and a Man. London: Thomas Bennett.

29. Wallen, K. & Hassett, J. M. (2009). Sexual differentiation of behavior of behavior in monkeys: role of prenatal hormones. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 21, 421-426.

30. Watt, H. (2017). Secondary school makes uniform gender neutral. The Manchester Guardian. September 6, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/Sep/06/secondary-school-makes-uniform-gender-neutral

31. Weisner, T. S., & Wilson‐Mitchell, J. E. (1990). Nonconventional family life‐styles and sex typing in six‐year‐Child Development, 61, 1915-1933.

32. Young, W.C.; Goy, Q.W.; & Phoenix C.H. (1964). Hormones and sexual behavior. Science, 143, 212-216.