US Election

FBI Director Comey: Straight Shooter or Feckless Careerist? How About Neither

FBI Director Comey's call not to charge Hillary Clinton aimed to avoid political turmoil in a charged climate.

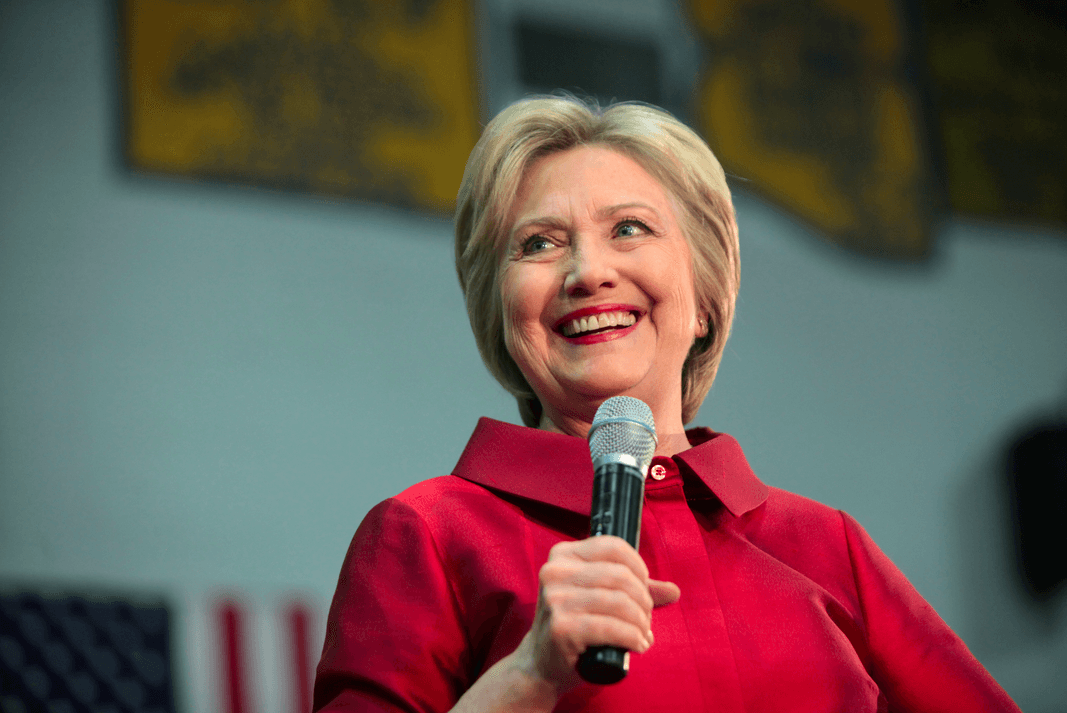

FBI Director James Comey’s recent decision not to recommend criminal charges against presumptive Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton for her mishandling of classified information vital to the US’s national security interests came as a shock to many, especially in light of Comey’s reputation as an honest and principled public servant, as well as his bipartisan palatability. (Comey, a Republican, was appointed to his current position by President Obama back in 2013 because of those qualities—though Kimberly Strassel strongly disagrees with this characterization).

Before stating that he would not recommend to the Department of Justice that charges be brought against Clinton, he laid out, in excruciating, painstaking detail, the extent to which Clinton’s own narrative regarding the alleged email scandal diverged massively from the facts of the case, unearthed by his Bureau’s extensive investigation. And yet, apparently “no reasonable prosecutor” would proceed with the case. Pace Comey, this beggars belief and cries out for explanation.

Some are crying foul, insisting that Comey must have received, if not an outright diktat from his boss, Attorney General Loretta Lynch, then an at least thinly veiled “stand down” message. These critics point to the attorney general’s prima facie suspicious, “coincidental” meeting in Phoenix, Arizona aboard her private plane with former president Bill Clinton shortly before Comey’s announcement as indirect evidence of corruption — an unmistakable shot across the FBI’s bow. Still others insist that Clinton has done no wrong whatsoever — that she was fully vindicated by the outcome of the FBI’s investigation.

Both sides are incorrect. Comey was not coerced, nor is Clinton blameless. Rather, Comey, in his role as FBI Director, recognized that his authority, at least in this election cycle, did not extend to disrupting the political process, irrespective of the relevant statute and rule of law considerations.

The fact of the matter is that, contra Comey, 18 U.S.C. section 793(f) does not require intent to convict, only “gross negligence.” And Comey himself said that Clinton was “extremely careless” regarding her handling of classified emails. To any fair-minded observer, to have exhibited “gross negligence” just is to have been “extremely careless”; so why did Comey let Clinton off?

Charles Krauthammer, in a recent New York Daily News column, argues that Comey did so because he “did not want … to end up as the arbiter of the 2016 presidential election.” This is true to an extent, but there are two additional considerations which Krauthammer does not explore. The first is understanding Comey as a mere cog in a machine much larger than himself, the second, endorsing the notion that he is shrewd enough to recognize the political tumult swirling all around him — both in the US and in Europe — and the potential hazards it represents.

When an individual is elevated to a position of authority within an organization about which they care deeply, over time they begin to think and behave more and more as though their every word and deed will at some point reflect back on their organization. Comey quite obviously desires to maintain the integrity of the Bureau, and he recognized rightly that either decision— recommending that Clinton be indicted or not — would carry with it repercussions. He is “thinking institutionally,” not personally.

At least this way, he does not risk presenting himself to the American people, and later on to the harsh gaze of history, as an unaccountable deus ex machina, swooping in only to swing such a widely-perceived-as-momentous election out of the Democrats’ favor. He ran the calculus and decided that the only way to escape the perception that he and, by extension, his Bureau were nothing more than covert kingmakers was to accept the white hot ire of anti-Clintonites and conservatives everywhere. So he did.

Second, Comey is no fool. He recognizes the populist fervor sweeping across both America and Europe. Brexit was the common folks’ stern rebuke of the consensus view of England’s leadership class: that a globalist, technocratically-oriented consortium of nations is best for all, issues of sovereignty be damned. And countries all over Europe are in thrall to populist parties deeply committed to ethno-nationalism and trade protectionism, positions which represent sharp departures from the post-WWII liberal democratic order, one committed to multiculturalism and free trade. Whether he inserted himself or not, then, Comey was opening himself up to charges of illegitimate meddling.

He was between a rock and a hard place: Either Trump’s supporters would cry Corruption!, or Clinton’s supporters would howl Vast Rightwing Conspiracy! He decided that, all things considered, abstaining from using his authority to obliterate Clinton’s campaign was a safer bet than being viewed as tacitly endorsing the populist tsunami sweeping the West, and its avatar: Donald J. Trump.

Of course, his not doing so both prompted even those largely sympathetic to progressivism to insist that the Clintons play by a different set of rules and bolstered widespread and growing suspicions among the American electorate that the rule of law — the idea that what you do, not who you are, is what matters in the eyes of the legal system — is severely compromised—if not dead.

I am a steadfast and vociferous proponent of the rule of law, because it is only our collective commitment to that principle which allows all people — irrespective of their wealth or fame — to be on equal footing in society. In Comey’s mind, however, enforcing it in this election cycle against Clinton, given the political insanity with which we have been inundated in the past year-and-a-half, would have been to inflict irrevocable damage upon our already fragile and destabilized constitutional order.

For some, the sheer magnitude of chaos cries out to us, requires us, even, to deviate from revered and well-established-as-efficacious principles. I believe that Comey truly believed that this was one of those moments, but I wholeheartedly disagree with his decision because I do not share his view that recommending that Clinton be indicted was to consign our republic to unadulterated pandemonium — that this was a “make or break moment” for us as a nation.

I am immensely frustrated that he allowed even the appearance of impropriety to go unpunished, and undoubtedly our current and would-be leaders most definitely ought be held to higher standards than ordinary Americans, but sometimes, politics trumps principle.