Security

Inaction is an Active Choice

A large section of the critics of intervention today are making similar assumptions in both the moral and practical assessments of the choices before us.

Everyone’s a critic. When it comes to Cameron’s case for extending airstrikes beyond the nominal border between Iraq and Syria, including the Western plan to defeat Islamic State, it is seemingly very easy to be a critic. When judged against perfection it always is.

In judging the success of previous interventions, critics tend to operate from a counter-factual assumption of suspended animation and zero deaths. For example, every death following the 2003 invasion of Iraq is added to the debit column of intervention yet no predictions of deaths from a maintenance of the status quo are added to the credit column, let alone any kind of assessment of what misery a collapse of Saddam’s regime would have created. You may well believe that after factoring in your understanding of these, the debit column is still by far the larger. This is a perfectly valid view but to fail to factor them in at all is to produce a worthless assessment of the decision. It also forms no basis from which to take pride in an apparent position of moral superiority.

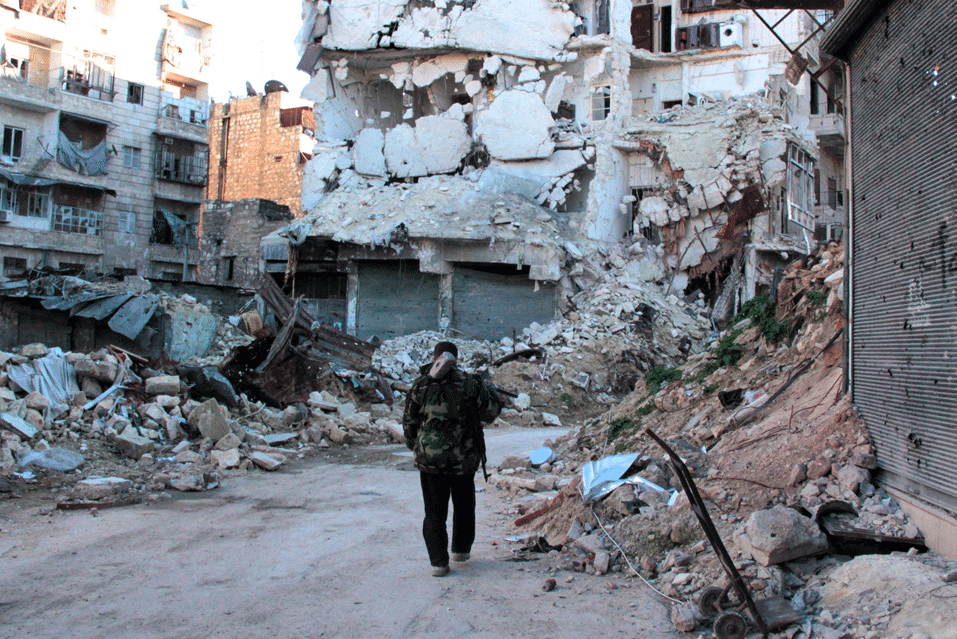

A large section of the critics of intervention today are making similar assumptions in both the moral and practical assessments of the choices before us. We are not in a state of suspended animation and merely mulling a decision to move. Things have been moving constantly and what we have and haven’t done up until now are all active choices. People are dying in bloody batches and will continue to do so, millions are displaced, over 200,000 are dead. We have not reached a fork in the road, we have erected one and every previous day we had a choice to erect it or not.

Apparently, action is far more culpable than inaction, though I am uncertain why this should be so. Being unable to decide what colour to paint your bedroom means you are choosing to keep it the colour it is.

Inaction is an active choice.

Moral philosophers have addressed this subject at length. The reductio ad absurdum of applying moral judgement to inaction is that each moment I spend at leisure makes me morally responsible for all the lives I could have helped using that time elsewhere. Accepting this, I cannot therefore pretend this is simple. However, there are elements in this specific case that affect the moral analysis.

The first is that so many in the anti-intervention camp already hold us (the West) as morally responsible for the situation as it stands. But they are part of the West too and they too are responsible even if they were against the decision. They are part of society, they vote for its leadership and they profit from our mutual cooperation. They cannot therefore have this both ways. If we are at all to blame then the consequences of the decision to make no decision is our responsibility as much as the consequences of making one.

A second is that so many are prefacing their objections to the currently proposed course of action with a statement of agreement with the imperative of action. Take this example from Corbyn’s new group, Momentum:

When diagnosed with cancer, choosing to do nothing is as much a choice, a plan, a decision, an action, as seeking treatment is. The various types of treatment all have different probabilities of success and nobody knows for certain how it will turn out. But one of the available paths, including doing nothing, is always taken.

A surgeon knows that each time he tells his anaesthetist to put somebody under there are varying odds that that patient will end up dying. They might make a mistake, something unforeseen might happen, they might not be able to achieve what they aim to. We accept that this might happen. We try and mitigate the risks by getting the best doctors to make the best calls.

What is the moral assessment to be made about the person who says that because the surgeon is unable to guarantee no risk they say: “Although we agree the patient’s complaint has to be dealt with, and although we have no sensible alternative treatment plan, we are voting for the patient to continue living with their ailment and if the surgeon tries and fails, in any way, we will blame them for the failure”.

Furthermore, claiming that the surgeon gave the patient cancer previously, which is a constant refrain here, surely works against them.

The anti-intervention case is predicated on the notion that those advocating a change in policy bear all the responsibility for what then happens whereas those advocating a maintenance of the status quo bear no responsibility.

The only way this could be taken seriously is if they make the case for what happens without the treatment. If treatment is to make the situation worse then surely this case needs a ‘comprehensive’ explanation as to how the opposite will create a better outcome.

The argument against this seemingly amounts to little more than: because a Westerner didn’t pull the trigger it is in no way their responsibility. This is fallacious, not to mention a complete betrayal of the principles of universal solidarity they tend to dress their opinions in. The fact that they might feel no responsibility for the current state of affairs doesn’t affect human happiness one iota beyond their own sense of immunity from guilt.

Ultimately this is about choosing a path from the various options available and, as it happens, none of them are even close to perfect. People stating opposition to the West’s current plan are not, as they seemingly fashion it, arguing against zero deaths or suspended animation. And while they have advocated an alternative, they are not fleshing it out, they are not making it ‘full and comprehensive’ and they are certainly not putting their names to it. If they did, then those opposing them could make lists of objections and shortfalls and potential negative outcomes just as easily while also exuding the same sense of moral superiority.

Cameron has been perfectly clear that there is uncertainty and risk in his proposal of extending British military activities into Syria. No serious person would have it any other way. There is no perfect solution here and pointing out a shortcoming in his proposal might certainly be useful in indicating something we must attempt to mitigate. This is an essential element to any planning process and must continue as we progress. However, this is different from using that shortcoming to reject the proposal while presenting no alternative. The rejection in preference of nothing is a positive choosing of nothing. Anybody doing this who is then unwilling to claim support of nothing, to spell out the ramifications of nothing, to call their nothing their plan, is simply not being morally serious.