Israel

How Hamas Exploits the West

Pamela Paresky speaks with Israeli political scientist Dr. Dan Schueftan about Israel’s resilience after October 7th, the moral imperative of defeating Hamas, and the shifting alliances reshaping the Middle East.

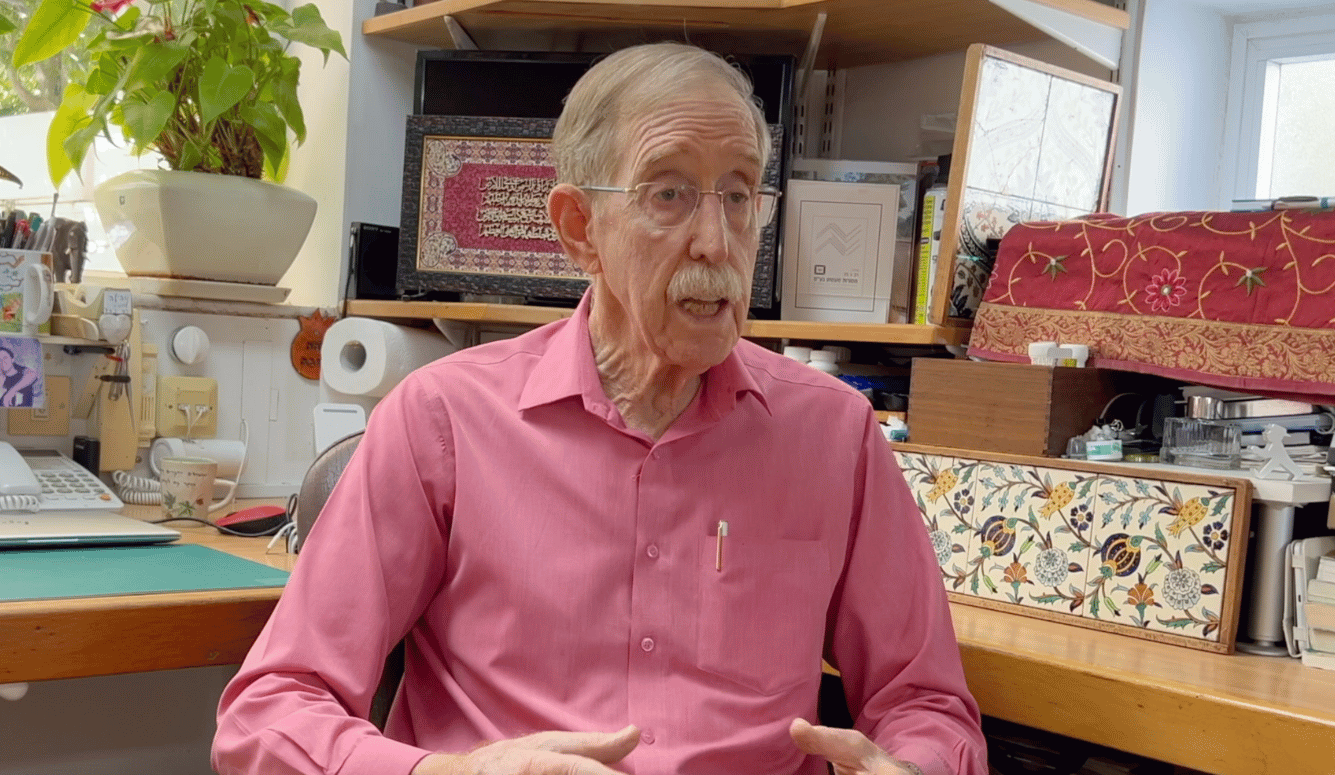

On 2 March, Pamela Paresky spoke with Dr Dan Schueftan, a leading Israeli political scientist and national security expert who has advised multiple Israeli prime ministers.

They discuss Israel’s resilience after October 7, the necessity of defeating Hamas, and the shifting alliances reshaping the Middle East. Schueftan critiques the influence of ideological extremism on Western democracies and urges a return to pragmatic, civic-minded liberalism.

The conversation also touches on leadership, minority rights, immigration in Europe, and the need for meaningful—not symbolic—social progress.

I. Israel is Winning

Pamela Paresky: What’s happened over the last seventeen or eighteen months? Where are we now?

Dan Schueftan: Well, now we know we’ve won the war. I always believed we would, but I didn’t know it would be this decisive. I’m delighted to say we’ve practically won. Yes, there’s still more to come—there will be pain, and Israel will be hurt again. But if you look at the big picture, it's more positive than I expected.

PP: That might surprise people—given the devastation in Gaza, that not all the hostages are back, and Hamas still holds power. How can you say Israel has won?

DS: Because I agree with what my grandmother used to say: it’s better to be rich, healthy, and young than old, sick, and poor. Sure, things aren’t perfect—but the real question is whether, overall, we are winning. If you understand what this war is about, I believe we are winning in a very major way.

Let me explain. This war is about whether civilised people can defend themselves against barbarians—even when those barbarians hide behind their own civilians. And many on the liberal side argue: “If defending ourselves means harming people who aren’t personally guilty, we can’t do it.” That’s exactly what the barbarians are counting on. Their main weapon is our values.

So, we need to demonstrate—and we have demonstrated—that we can defeat barbarism without losing our moral compass. That we can be like Sparta toward our enemies, while remaining like Athens among ourselves and with others who are civil and can be negotiated with.

Now, this has become much harder in the last forty to fifty years, especially since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Why? Because after that collapse, the West assumed liberalism had won, and we could afford to tie not just one, but both hands behind our backs.

Liberals used to believe that you fight with one hand tied so as not to become like your enemy. But progressives went further—they said you shouldn’t be allowed to fight at all, especially if your enemy has darker skin. If your enemy is black or brown, then he must be right, and you must be wrong. It’s one of the most racist attitudes I can imagine: If you’re white, you’re guilty; if you’re not, you’re innocent.

And it excuses barbarism. “Well,” they say, “he suffered from slavery or colonialism, so his behaviour is understandable.” This thinking ignores that it was white people who ended slavery, which had been a global norm. And colonialism? That’s just a new name for something that has defined most of human history: the strong seeking to dominate the weak. What changed was that we decided to stop.

So this distorted, sick, progressive ideology has weakened us and strengthened our enemies.

And then there’s technology. Today, a bunch of primitive tribes in Yemen can launch ballistic missiles. Think about that: thirty or forty years ago, only superpowers had that kind of weapon. Now you can buy off-the-shelf tech, modify a toy, and turn it into a precision-guided munition.

This means we, the stronger side, are denied two critical tools:

- The ability to ignore the enemy—to say, “this is unpleasant, but not an existential threat.”

- The ability to destroy the enemy’s capacity to hit us back. Even if we destroy most of their capabilities, what remains can still strike at our population centres.

And this is only getting worse. With advances in biotechnology, enemies could soon produce dangerous pathogens in their kitchens and wage biological warfare. That means we can’t ignore them. We can’t fully destroy them. So the question becomes: can we fight them successfully?

Hamas believed it could win—not because it was stronger, but because Gaza had become the most fortified place in history. Fortified not just with missiles and tunnels, but with CNN, The New York Times, the BBC, the courts in The Hague, Amnesty International—every institution dominated by the autocratic, dictatorial, or barbarian-majority world.

These institutions undermine democracy while pretending to defend it. When countries like Libya, Syria, North Korea, and Venezuela define “human rights” at the UN, the result is absurd.

So Hamas gained power through media, international courts, and ideological corruption. We, on the other hand, became weaker because progressives prostituted liberalism.

Let me step back and make a broader point: the worst enemy of something good is the pursuit of something perfect in the same direction.

You can’t have democracy or human rights without nationalism. Why? Because solidarity—beyond family or tribe—only works at the national level. People say, “I’ll sacrifice something for someone else, because in the long run it benefits all of us.” Nationalism is necessary.

Who is the enemy of a patriot? A hyper-patriot. A fascist. Just like too much nationalism kills nationalism, too much liberalism kills liberalism.

If, in a war, we say: “Let’s try to reduce civilian casualties, even on the enemy side”—yes, that’s a good liberal instinct. But if we say: “The moment civilians are harmed, we must stop”—then we hand victory to the barbarians. Because they want civilians to be harmed—it’s their shield and their strategy.

If that’s our rule, then Western civilisation is finished.

In Gaza, Israel understood: If we don’t respond forcefully, we’ll spark a regional war. Arab leaders—those who aren’t radicals and are willing to accept Israel—will lose public support. The message will be: “You can rape Jewish women, decapitate civilians, burn babies, and get away with it.”

The only way moderate Arab governments can withstand public pressure is to point to Gaza and say, “Do you want that in Cairo or Amman?” That’s their defence.

So to preserve even relative Middle Eastern stability—which is rare—we had to defeat Hamas decisively. We’re not finished yet. We’re still waiting for more hostages to be released and for Hamas’s military capacity to be fully dismantled. But we have won.

And we’ve won on three levels:

- Regionally

- Internationally

- Domestically (hopefully)

Let me describe each of these.

In the Middle East, our position is stronger than ever. Most Arab states not only accept Israel’s existence—they’ve realised they need Israel. Why? Because their enemies are the same as ours: Iran, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the strategic ignorance of the United States.

The US is much more powerful, but Israel is more dependable. America might elect a president like [Barack] Obama, who sides with enemies over allies. But Israel doesn’t have that luxury. We fight because we have no choice—and we’ve shown we can fight. We can defeat Hamas. And we will.

Hezbollah, once a strategic threat with no clear Israeli response, is now just a serious nuisance. A problem, yes—but before this war, we had no answer to it.

Then, against American advice, Israel dropped 84 tonnes of bombs on Beirut in seconds. That’s how you deal with barbarians. They go after our people—we go after their sanctuaries. They must understand: They can run, but they can't hide—not behind the UN, not behind the BBC, not behind CNN.

We’ve severely damaged Hezbollah. We’ve also shown how vulnerable Iran is. We destroyed key parts of its air defences. When they threw everything they had at us—ballistic missiles, drones, cruise missiles—the result was unpleasant but barely consequential.

Iran is weaker now. Its proxies have been hammered. And Arab states saw that Israel could do this without losing US support.

What Saudi Arabia and the UAE want is this: good relations with Washington, but without having to follow Washington’s strategic advice—because that advice is consistently wrong.

When Biden took office, he removed the Houthis from the terror list, gave them humanitarian aid, and pressured Saudi Arabia and the UAE to ease up. His administration thought, “If an alligator attacks you, give it a banana.”

But what happened? The Houthis attacked US, Israeli, and British ships. They disrupted fifteen percent of global trade in the Red Sea. They starved Egypt of Suez Canal income. Egypt now only survives on tourism (which is low) and the Suez Canal (which is blocked).

So the Saudis and Emiratis want to keep ties with America—but ignore its strategic guidance.

PP: So what is it about Washington’s advice that misses the mark so completely?