Blog

Escaping Cuba: Quillette Cetera Episode 38

A conversation with the Cuban student, poet and free-speech advocate, Justo Antonio Triana.

Justo Antonio Triana is a Cuban poet, novelist, and free speech advocate. He is studying classical civilisation at Syracuse University and is interning with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE).

In this conversation, Justo reflects on his experience growing up in Cuba under a dictatorship, highlighting the pervasive poverty and lack of freedom. Justo critiques the idealised vision that the Western left hold of Cuba, and expresses his disappointment in escaping oppressive Cuba only to experience cancel culture and self-censorship on American campuses.

This conversation also includes a reading of Justo’s poetry.

You can also read an edited transcript of the conversation below.

Zoe Booth: Could you tell me a little bit about how it was growing up in Cuba and how you came to move to the States?

Justo Antonio Triana: First of all, the Cuban experience is not standard. It depends on what social class you grew up in. In Cuba, the social classes are different than those in a democracy. We have the families of the ruling class at the top. Then we have people who have positions with the government where they can divert funds. Then we have people who receive money from their families outside, and then there’s everyone else. The vast majority of people are poor but those in those first three classes are a little bit better off. My family didn't belong to any of those classes which means that my parents had to work a lot.

ZB: What did your parents do?

JAT: My father was a musician and professor of music history and my mom was a professor of environmental law.

ZB: What was their experience like working in academia?

JAT: I don't think that they had to deal a lot with politics because their fields were not really that political.

However, if you work for the government, which is the vast majority of people, then you have to go to communist parades like May 1st. That's why you see the images of everyone marching because they don’t have the option of not going.

ZB: Did you have to attend those matches as a student?

JAT: Oh yeah. As a student, every day in the morning you start by repeating communist slogans and singing the national anthem.

ZB: How old are you when you start reciting these slogans?

JAT: Since you're like seven, perhaps a little bit younger. As soon as you join school they teach you all this.

I think my generation didn't even take it seriously. I think my parents’ generation was a lot more serious but my generation was like: we're doing this but none of us believe what we're saying. That's a change that was very, very interesting that happened in Cuba after the 90s and the collapse of the Soviet Union. My generation grew up with a lot of American influence and that was not the case with my parents’ generation. They were influenced by the Soviets.

The regime became softer and more flexible still after the 90s. They killed people from time to time like when the person was a very important leader of the opposition and they became too popular, like Oswaldo Paya. He was killed in a ‘car accident’ and now his daughter is a big Cuban activist for freedom.

It was more flexible with my generation but we still had to sign letters condemning the US embargo and supporting Maduro. The teachers basically just came to our classrooms and said: Hey, you have to do this, you have no option, this is my job and I don't even agree with this but I have to do this.

ZB: Growing up, were you aware that you were living under a dictatorship?

JAT: Not really at first. I think that's a process and it depends on what family you grow up in. In my case, I realized it because my father would talk a lot about politics at home. He and my mom would criticize what was going on in the country, the government and the leadership. Then they would tell me “Do not repeat this at school.” That's also something that makes you realize that you live in a dictatorship, the fact that you have you have to be careful as a kid of the things you say at school.

ZB: What's your reference point? What do you have to compare Cuba to?

JAT: When you are growing up in Cuba, you are constantly hearing of people that are leaving the country and then you start thinking like “Why are they leaving?” You also hear that those people are making a lot of money outside the country and that those people are sending money to their families inside the country. Then you say “It's difficult to live, these people are outside the country, in a country where they are not even speaking their first language and they're making more money. Why is this?” At the movies we also see a reality that is not ours.

ZB: How bad is the poverty?

JAT: Only rich people can afford air conditioner. This is when I was growing up. I don't know what the situation is like now. I left the country in 2019. Until that moment, only the rich people could afford an air conditioner. That was a luxury. My parents were university professors but we couldn't afford an air conditioner, a car or even a motorcycle. My parents had to hitchhike to go their jobs every morning. That's a big thing in Cuba. There's not a lot of cars. Cuba has lots of old cars not because people just like antiques. It's because we cannot afford new cars.

ZB: Are new cars even imported into the island?

JAT: There are some new cars that are imported but the government sells them at extremely expensive prices. Their prices are insane. A price of a car that would cost like $5,000 in the US is like $30,000 in Cuba.

ZB: What's the housing situation like? Do people own property?

JAT: Lately yes. There's more buying because a lot of people are leaving the country and they're selling everything.

What people did before and usually do is they just live with their parents forever and we have like three generations of people living in the same house.

Tourists come and they say “Wow look at Cubans they love their families so much.” Except, it's not because we don't want to get independent, it's just because we cannot afford to.

Tourists come and they see the Cuban reality through their own eyes. They say Cubans like to recycle so much and in reality we cannot afford anything therefore we have to recycle everything. They see the kids on the streets playing barefoot and they say what a beautiful childhood those kids have but we're playing on the streets because we don't have anywhere else to play and also because there are no cars in the street because no one can afford a car.

When you look at pictures of Cuba in the 1940s or 1950s it looked like New York. It's vibrant with cars and the streets full of people, but nowadays it looks like Gaza.

ZB: Is it safe?

JAT: No. It is not safe. It is very violent. It's much more violent than in the US. The difference is we don't have guns so people get killed with knives and machetes instead.

It depends where you go during the day. It's mostly safe in most parts of the country but at night it is not safe. It's safe if you're a tourist because the government takes care of you in a certain way. They punish people who do things to tourists harsher than people who do things to other Cubans. I've known cases of people getting killed for a watch or for a bicycle and that's very common and that was not the case before Revolution.

ZB: What about for women? What's it like as a Cuban woman?

JAT: I cannot speak for women from what I've experienced, but there's a lot more violence against women because the Cuban culture has stagnated since the 1960s. There has not been a feminist movement or anything like that and also there has not been a movement against racism in Cuba, there is a lot of racism, and it's simply because according to the regime these issues were solved with the Revolution therefore there's no reason to do anything about them or to discuss them.

I've heard feminist in the US say that the Cuban parliament has more women than the US parliament and Cubans are so progressive. Well, the power they have is not real power. You can have like 100% women in your parliament but at the end what power do they have? They don't have a voice in anything.

ZB: I remember when we first talked, I made a comment about ballet because I didn't know much about Cuba aside from that you produce really good ballet dances and I love ballet. That was probably a naive comment because you explained the reason why you have such good ballet dancers.

JAT: Yeah we have good ballet dancers and we have good sport people.

ZB: Chess right?

JAT: Chess players but also boxers and baseball players. It's because in Cuba if you want to play a sport you have to go to a specialized sports school, the same if you want to play music, you have to go to a special music school. That was my case. I studied violin in a music school but they train these people to be champions. It's good for the regime because it gives Cuba international recognition and it's a way of saying we're a little island but we're so important and the Revolution has done great things for Cuba’s athletes.

ZB: It's like China constantly trying to show off. What's the relationship like between China and Cuba?

JAT: They are allies, political allies, but I think that the Chinese government has realized that there's no money in Cuba at all and there's no real reason to invest there. Venezuela they are more interested in because there's oil there but in Cuba they don't really care. I guess they allow the Cuban government to sustain itself but there is no real exchange in the sense uh that there was an exchange between Cuba and the Soviet Union in the 80s.

ZB: What about with North Korea?

JAT: It's the same thing. North Korea doesn't have money for itself so there's no real trade or anything with North Korea.

I wanted to talk about the myth of Cuban healthcare because that's another important angle. In Cuba, tourists go to hospitals that are not the hospitals that Cubans go to, therefore what they see there is completely different from reality. The Cuban hospitals are in such a situation that that people die from infections that they get at the hospitals. It’s that bad. On top of that there are no ambulances. People get to a hospital in whatever they can. Sometimes even horses. There are pictures of wounded people going to hospitals in horses. It's just crazy. People say that this is because of the embargo but the Cuban regime has very, very new and very sophisticated police cars. So how do you explain that? How do you explain that there's no ambulances but there are a bunch of new police cars?

ZB: What are the police like?

JAT: It depends. There are police that are like the traffic police or whatever and they don't care too much about anything. They're just there. Then there is the political police which is the one who takes care of the dissident and anyone who post their own thing on Facebook.

ZB: Your social media is monitored?

JAT: Oh yeah. There are many, many websites that cannot be accessed in the island so most people use VPNs if they want to see any controversial or problematic content.

ZB: What about access to food, water and electricity?

JAT: Electricity comes and goes throughout the day, especially lately there have been periods where it was better. I think when I was growing up it was better but now they get like eight hours without electricity but they never know when it's coming and when it's going. It's just very unstable.

In terms of food, again when I was growing up it was a little bit better. I was never hungry and I don't think that most of my friends were at any point so that's good. However nowadays I've seen many videos and I've heard many stories of people actually not having enough to eat. Some family members of mine have been there lately and they have told me that the levels of people living on the streets are just more than when we lived there.

ZB: Does everyone have a job?

JAT: No. I don't know what's the unemployment rate but what's also happened is that the government allowed little private enterprises after the 2000s and people slowly have been creating a private sector. Before that everything was state owned and controlled but lately there are small businesses, like restaurants. But People who work there are still not free because if they say something against the regime then it threatens to cancel the license of the restaurant or whatever. They always have this means of controlling people.

Also, the government jobs don't pay well at all. My grandma was a dentist. If she had been born in the US she would be a millionaire by now probably. In Cuba, her salary after retirement was like $10 a month. It's just insane. She was surviving in Cuban with the money that my dad was sending her and it's the same thing with many Cubans. Many Cubans are surviving due to their families who live outside the country and it's a huge extortion. The Cuban government makes it difficult for the families to leave in order to keep getting all of this money from outside.

ZB: How do you leave? What's the process like in packing up your life and leaving?

JAT: It's not like applying for a job and you just go. I had a friend that recently left and she got a scholarship from some international organization and she did all that only to get out of Cuba and once she was outside, she applied for political asylum. Musicians often find contracts and they talk to people outside the country. There are many Cubans in the in the United Arab states because that's another country that doesn't require Visas, therefore many Cubans go there and just to survive they play music or whatever. Some have family outside and they get claimed through family reunification.

ZB: Is it easy for you to go back to Cuba? Are you on some sort of a watch list?

JAT: I cannot go back because I have published many articles talking about how the situation is inside and I went on an interview with Fox. I'm definitely blacklisted so there's no way I can go back there. If I went back, the regime would immediately put me in jail. There's no way for me, but at least my family from time to time goes back.

ZB: When tourists go to Cuba, they see the beautiful beaches and things like that. Do everyday Cubans get access to the beach?

JAT: No. My family lived in Camaguey, it's a province to the East, and we got to go to the beach like once a year and we lived two hours from the beach.

It's a beautiful beach. Cuba is a beautiful country. That's not a lie but Cubans don't get to enjoy it, and I've met so many people in the US saying “Wow I've gone to Varadero, it's the most beautiful country ever” and I'm like “Wow you know I was never able to go to any of those places.”

ZB: How do Cubans feel about tourists?

JAT: I think most Cubans actually like that we have tourists because that's a way of earning some cash or potentially leaving the country. It's unfortunate but many Cubans try to marry anyone who goes to the island just to get out. It's a thing. Overall, it's positive. It's the only chance they have to get some money. That's why taxi drivers are so well paid in some cases.

JAT: Is there sex tourism?

ZB: Definitely. I think Cuba is famous for that unfortunately. I think it’s like Thailand in that there are many people who go there just to have sex and I've heard stories of minors getting into that just for money. It’s disgusting but it's a reality.

That wasn't the case before Castro. There were brothels but whoever was there was a small portion of the society and it was not something normal. Nowadays it's something normal and something that is ingrained in the Cuban culture. If you read any book of modern contemporary Cuban literature, it's full of experiences that have to do with misery, sadness, nostalgia and/or prostitution.

ZB: In Australia Cuba doesn't occupy much of mental bandwidth but it's really sad how it's sort of just forgotten about. We talk so much about Palestine or Ukraine or Taiwan and China, maybe a bit about Africa, but I think people forget what Cubans have been going through for decades.

JAT: I kind of understand why that is. People are just tired of Cuba because it's always the same. The situation has not changed in 60 years, so it's not even an attractive topic anymore. Ukraine and what's happening in Gaza are the new thing.

ZB: The same argument could be made about Israel and Palestine? I mean that's been going on and on and on.

JAT: Yeah. I guess the Cubans are experiencing a slow and painful death. So there is nothing as attractive to show. There are no bombs falling.

ZB: There's no like white oppressor. It's more the government oppressing its own people.

JAT: That's another thing of course. Cuba is seen as this little island fighting against the US imperialism, so no one cares, especially people who have this resentment against the US. They just simply don't care about what's going on in Cuba.

ZB: What about religious freedoms?

JAT: That's another thing that became more flexible after the Soviet Union collapsed. Before that, I remember my mom had to hide in order to practice Catholicism, which is funny because it's the main religion in Cuba. I would say more than 60% of the population is Catholic, but still there was a lot of pressure at the time.

After the 90s it was flexible and I guess the Cuban government has also used religion to manage the situation. They control what the religious people say for the most part. There are a few religious leaders that are more confrontational with the regime but the majority comply.

ZB: Do you have elections?

JAT: We do we have elections but of course they're not democratic at all. What happens is some member of the neighborhood goes and nominates himself or herself but of course they have to have a record of supporting the Revolution. If you don't support the Revolution, you don't get elected. They simply don't let you participate. People from the neighborhood elect one of these people from the district and then the people that get elected in the district get to choose the one in the municipality and everyone that gets elected in the municipality votes for the one in the province and then those from the province vote. It's many, many, many layers and at the end you're not electing anyone. It doesn't even make sense at the end because all of those people belong to the Communist Party. There's no other party. That's a democracy of a communist country.

ZB: As a child, what are you taught about the history of Cuba?

JAT: They call the Republican period of Cuba the neocolonial period. So that's how we learn it. It's like we never were free until Castro came to power. It's like we made all of these wars of independence and then in 1901 or 1902 the Americans came and they controlled the whole island until 1959 when Castro came and liberated us, which is not really the case. Even the previous dictator wasn't an ally of the US.

ZB: The previous dictator, who was that?

JAT: Fulgencio Batista. That's another story. He was also terrible and he was actually the reason why we got Castro later. Batista made a coup and he destroyed the Republic and then as a result Castro started this movement promising free elections, promising what we had had before and at the end he lied and the rest is history. But they frame all of these previous governments that Cuba had as like puppets of the US when it wasn't true. Some of them were but the majority were not.

ZB: What about further back like the Spanish influenza and that colonial period and slavery? How does that fit into the narrative of what's told to you?

JAT: I would say until the 1900s they teach it closer to reality because it doesn't affect them. The history that they completely manufacture is the one from 1900s when Cuba was independent to 1959.

ZB: How would you describe the history of Cuba for someone who doesn't know anything about it?

JAT: It's the history of an ideal of a country that never happens. We're always really close to it, we're always really getting there, and we had bright thinkers and people that envisioned a country that we have never had.

ZB: Tell our listeners a little bit more about your poetry. How long have you been writing poetry?

JAT: I became a poet because I used to go to the house of a poet and political dissident from my hometown and there I learned my passion. I started when I was like 15 or 16 but then I was completely sure that I wanted to be a writer by 17.

ZB: Have you published a book of poetry?

JAT: Yes I published La condena last year actually and this year I'm trying to publish my first novel Migrant's Luck.

ZB: What's that about? I suspect it will lead into what I wanted to talk about next which is your move to America.

JAT: Yeah. The novel is about a Cuban immigrant that is escaping communism and he does this whole trip through Central America which many Cubans have done. I interviewed three or four people in order to get the sense of what actually happened there because that was not my case, thank god, but once the protagonist gets to the US then something happens and the system changes in Cuba. All of this happens in 30 years into the future, 30, 40, or 50, I never say what year. Then he is faced with this situation of he escaped and went through hell to escape communism and now that he’s here the reason he’s left is not there anymore. On top of that there is also love. There's some romantic things there because he had a girlfriend there and now in this new country he starts like suffering because he's not with her anymore and then there's another girl who comes into play but I don't want to tell you the end.

ZB: Sounds good.

JAT: Yeah. It's adventure. I would characterize it as a very philosophical very anthropological, political adventure, because of course I like to philosophize a lot so I go into many different topics.

ZB: I can't wait to read it. You talked to people who came to America by foot or by boat up through Central America, and that wasn't your case. Talk a little bit more about the people you talked to and what they went through.

JAT: What's going on is that most countries in Latin America and in the world don't let Cubans just travel there. They require a Visa but because the Cuban government wants to get the pressure out of its shoulders and they don't want a 2021 protests happening again then they let all of these people out or they negotiate their exit with countries like Venezuela and Nicaragua, which are of course the triangle of evil in the Caribbean. So, these countries don't require Cubans to have a Visa and therefore Cubans when they want to leave the island if they don't want to use a raft, which is extremely dangerous even though thousands have done it before, they sell everything they have and then with that money they pay for a plane ticket to go to Venezuela or Nicaragua. Once they're there, they pay coyotes, which are like guides.

ZB: Smugglers?

JAT: Exactly.

The people who go to Venezuela have it harder. What they have to do is they have to go to the southernmost town of Colombia and from there they go on a trip to Panama but this trip can last anything from four days to two weeks through the jungle and it's really dangerous. The jungle is filled with animals but also humans and the humans are worse than the animals. They're paramilitary groups and all kinds of people who shouldn't be there like drug cartels. We have had many cases of Cubans being raped and killed. Once they reach Panama, they still have to keep paying police officers so that they don't deport them because the whole region is also very corrupt. So, it's a struggle. In Mexico, they have to be careful with the cartels. They have to negotiate how to get from the south to the north without being detained by the police in which case you would have to pay more money and all of this is to get to the US and apply for political Asylum there.

ZB: Can you tell me how you became interested in free speech and your experiences on American campuses?

JAT: When I arrived in the US in 2021, I was in the last year of high school. I started talking to people and realizing that they had no idea of what was going on in Cuba. Many professors were really nice people but they simply were ignorant about what was going on there and they had this idea that everything was fine and that scared me, because in Cuba you're thinking the world knows what these people are doing to us but when you actually go out of the little bubble you realize that now the world doesn't know anything about what's going on there, and the people who are actually telling the truth no one believes them. They don't go on CNN or anything like that.

So, I started trying to talk to them, convincing them of these things and, I think it's because many Americans are so skeptical of their own government, that they trust anything that the enemy of their government says, it's like the enemy of my enemy is my friend, on both sides which is very naïve.

Both sides of the political Spectrum are naive in that sense. Months and years passed and my English got a little bit better and then I started getting more of what was going on in the US because at the beginning I was just concerned about Cuba, but then when you live in a new country you start learning about what's going on here and the problems that this new country has. I realized that there was free speech to talk about everything but in reality like there's a lot of fear. People are afraid of speaking on topics that are controversial. There’s no government telling you what to say however everyone is afraid because of the other people. It's just crazy. Students don't say what they believe because they are going to be shunned, basically like no one wants to be your friend. They call you names just for saying common sense and just expressing yourself. When I got to the university, I realized that there was a whole issue there with free speech, not only because of the students censoring themselves and others but because the professors themselves were not going into certain controversial topics for fear of being denounced by the students.

This problem has many layers and one is that US universities are like big businesses. So, students pay a lot of money to go to these universities, therefore the administrations want to give them the privilege of feeling comfortable when that's not really the purpose of a university. The purpose of a university is seeking truth. As a result, the students have a huge power over the administration and the administration feels that they owe the students for their money and as a result they force the professors to not say any controversial stuff that would harm the feelings of their students and customer.

ZB: The same thing happens in Australia. I think in Europe, where higher education is more affordable, universities are run less like a business and more like how universities used to be run. I lived in Spain for a while and I saw that people got failed all the time at uni in Spain and in Australia you almost never get failed because you've paid so much so you sort of have to pass.

JAT: It's the same in the US. In the 70s, it was really difficult to get an A. Now almost everyone gets an A all the time.

I also studied in Europe and could see that there's a difference in also the amount of freedom. I've experienced this. I've had professors tell me I cannot talk about race I cannot talk about religion, I cannot talk about gender. These are the new taboo topics. They never get into those because they know they can offend someone just by expressing an opinion that is totally valid. They don't even have to be offensive in order to get expelled or to have their contracts suspended.

That's why I'm now working at FIRE, the Foundation for Individuals Rights and Expression, because I felt that this country also has a lot of problems in terms of free speech and I wanted to at least help make it better, raise awareness of what's going on. It's just insane. I've also had two or three professors send me long emails after having a small disagreement in one class and it's because they're afraid and you can feel that when you read the emails. It's like I value your opinion so much and I'm so sorry that maybe you felt a little bit offended with this or whatever. In reality, what they're saying is “Please do not denounce me” with the university inquisition. Do not say that I offended you.

ZB: To finish up, what would you have to say to people in the West who are sympathetic towards socialism?

JAT: I could say so many things, but I would say just talk to people who have who have lived in that system. I'm not talking about Finnish and Danish people because what they have there is not socialism. Just talk to people whose governments you defend. If you defend the Cuban government, talk to Cuban people. If you defend the Venezuelan government, talk to Venezuelan people. Hear what they have to say and maybe you will change your opinion. Just know the governments of these countries have facilitated your access to firsthand experiences by exporting Cubans and Venezuelans because of regimes and the oppression that they exert on us. So, if you have that advantage, take advantage of it.

ZB: Are you optimistic about the future of Cuba?

JAT: Well, if the Roman Empire fell, the Cuban regime has to fall. I don't think there's an evil that can be eternal.

I don't know when the change will happen. I think that it won't last more than 20 years because my generation was really like anti-communist and the children of my generation will be even more anti-communist, so I don't think there's any going back. There will not be a communist revival or anything like that. In Cuba, people are so over it. I have hope. I don't know when it will happen but I have hope.

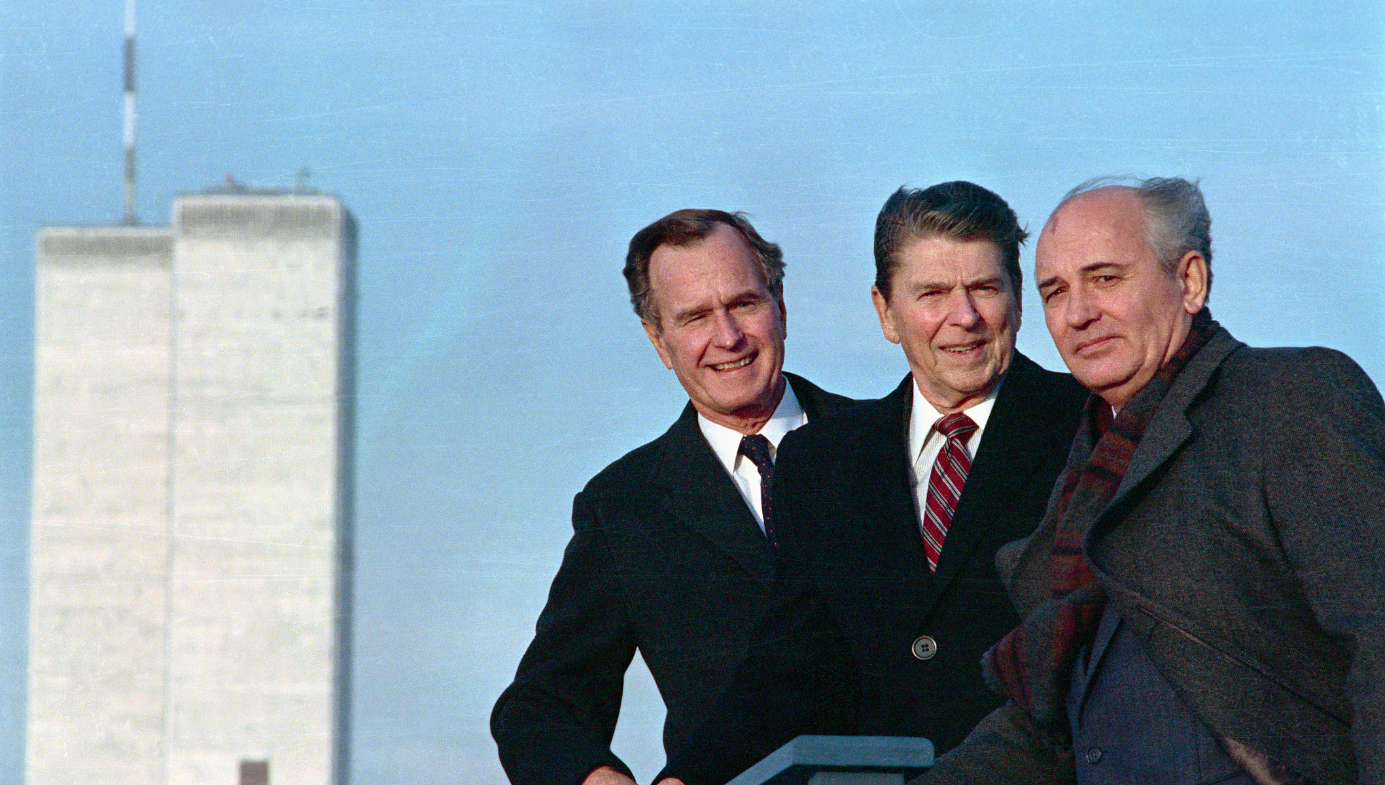

I don't think will happen in a violent way because the government has all the weapons. We don't have a second amendment in Cuba therefore there is no chance that the people can do that by themselves. What I think will happen is that there will be like some Gorbachev. I think that's the only the only way out of it.

JAT: How did you come across Quillette?

ZB: Good question. I guess on Instagram. One day I read something and I liked it. The way it was written and I just started reading the articles because they were so interesting. Quillette doesn't publish just news. It's more in-depth articles in. It's smarter content. So that's why I follow you.

ZB: Did you come across FIRE after us or did you already know about FIRE?

JAT: I also came across FIRE by accident. I was searching something on the internet, I don't remember what, and then the website came, I opened it and I said “Wow, is it real that there's an organization that cares about free speech?” So I followed them and then I think they sent me an email advertising the Summer Conference which I'm now organizing. I came to Philly and I loved it because it was refreshing. So many young people that actually care about free speech and they don't care about what you think but they care about your right to say it and I was like “Wow this is my place,” so then I applied for an internship and I got it.