Wokeness

Don’t Use the W-Word

Trumpeting your wokeness—or anti-wokeness—won’t do anything to fix society’s problems.

What does it mean to be “woke”? If you ask talk show host Joe Walsh, a former Republican politician who’s migrated leftward and now regularly denounces the GOP, being woke “just means being empathetic. And tolerant. And willing to listen. And open to learning.” On the other hand, if you ask writer Wesley Yang—a public intellectual whose politics are decidedly “anti-woke”—the word means “active discrimination to obtain equal outcomes across identity groups, dismantling law enforcement while policing speech and thought, and sterilizing gay, autistic, and gender-nonconforming children.”

No, it means active discrimination to obtain equal outcomes across identity groups, dismantling law enforcement while policing speech and thought, and sterilizing gay, autistic, and gender-nonconforming children https://t.co/6iDBXGKT3R

— Wesley Yang (@wesyang) January 19, 2023

If you ask a dozen other people who identify themselves as “woke” or “anti-woke” the same question, you’ll probably get equally polarized answers. Which is to say that the word “woke” has lost all useful meaning when it comes to communication between people on opposite sides of the culture war.

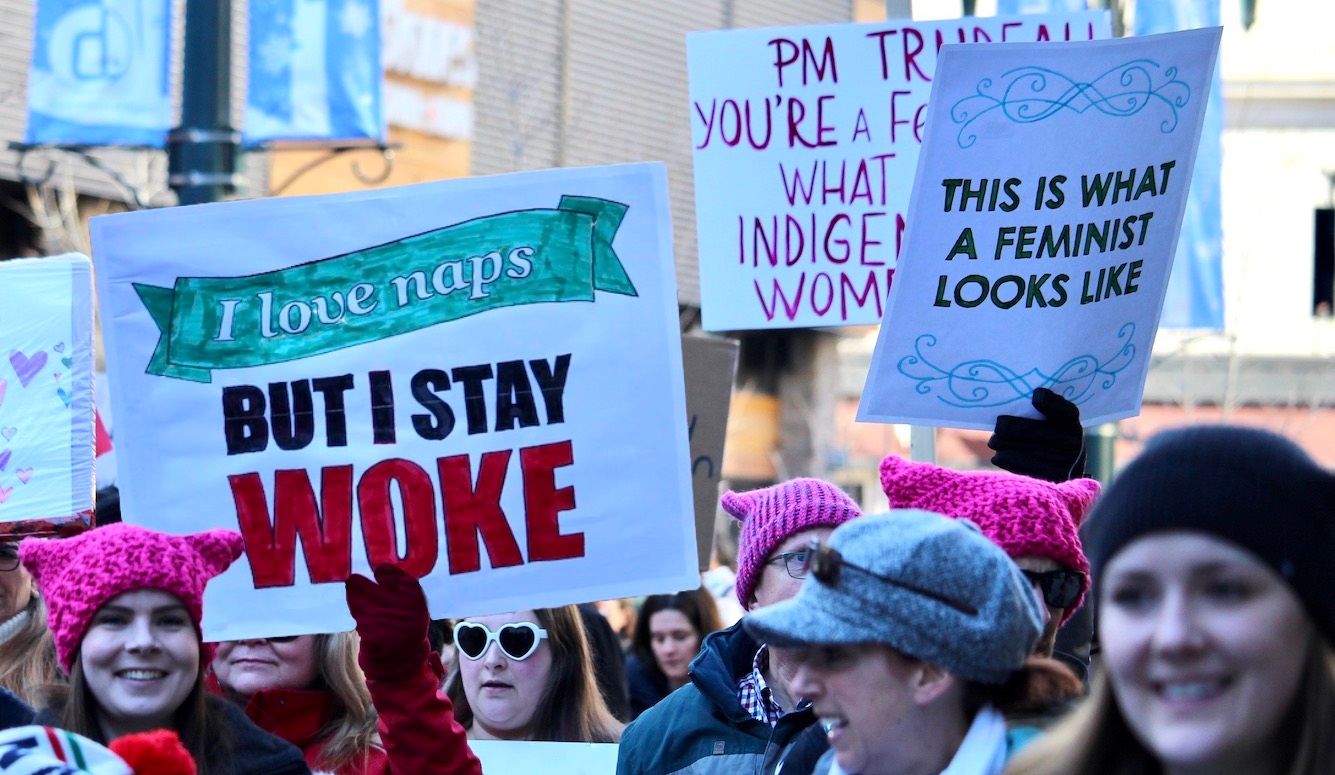

The use of the word “woke” as a political descriptor originated in the African American community; and signified, loosely, that the described person was conscious of the social and systemic issues plaguing marginalized groups. Over time, it morphed into a description of a wider movement that ostensibly advocates for the broad unobjectionable values that Walsh listed, while also pushing for more sharply defined political positions relating to racial equity, systemic racism, and gender rights. This, in turn, spawned a conservative counter-movement that co-opted “woke” as a pejorative term for describing people who exhibit excessive (and potentially harmful) beliefs and behaviors under the guise of nominally inclusive, sunny-sounding ideas.

Whatever it’s supposed to mean, use of the word “woke” forces individuals into one tribe or another, even when almost all of us have complex beliefs about the underlying societal issues in question. For instance, I believe that systemic racism is a real phenomenon that’s worth discussing and being concerned about. I’m for doing what we can to restructure society to mitigate inequities. I’m not against the implementation of (sensible) Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion policies. Does that make me “woke”?

Before you decide, you should also know that I think defunding the police would be a disastrous idea. I believe most modern anti-racism campaigns are, themselves, racist and counterproductive. And I am emphatically against policing speech, deplatforming, and the claim that words are “violence.” Does that make me “anti-woke”? I’ve been called—or accused of being—both.

The slew of comments under Walsh’s tweet and Yang’s rejoinder to it illustrate how divided we are on the meaning of “woke.” As with most culture-war conflicts of this type, discourse around the word’s meaning consists almost entirely of people talking past each other. This inhibits us from effectively addressing the problems that woke ideas are supposed to solve—which is what should matter to everyone.

This phenomenon is closely related to another that I view as equally rampant, which I call linguistic parasitism. It’s the motte-and-bailey rhetorical phenomenon that unfolds when users of a word or term implicitly expand its meaning so as to encompass more and more conceptual ground, while also simultaneously taking advantage of the visceral reaction conjured by the original, commonly understood meaning. For instance, up until about a decade ago, when someone was accused of racism, it would typically indicate heinous beliefs and behaviors—such as active discrimination, promotion of vicious stereotypes, or a general demonstration of hostility on the basis of skin color, ethnicity, or ancestry. Today, though, “racism” can mean that you voted for the wrong political candidate, or expressed support for the wrong celebrity. If you run a business, “racism” can mean that there aren’t enough people of a particular group in your workplace.

Accusations of racism still cause severe offense and alarm. But the substance of the underlying accusations has become more and more diluted. Eventually, people stop taking the accusation seriously. What we’re left with at that point is the carcass of a word, and a newfound inability to articulate (and denounce) an age-old evil. The parasite has devoured its host.

That’s why progressives should join their political opponents in helping to preserve the true meanings of terms such as “racism,” “violence,” and “trauma.” Those words describe serious problems in our society. And if they become meaningless due to dilatory misuse, that’s disastrous for our public discourse.

If you are on the “anti-woke” side of the culture war, you may argue that we need a term such as “woke” in our verbal arsenal for similarly constructive reasons. Surely it’s important, writers and commentators such as Substacker Freddie deBoer will argue, that we have some shorthand way of identifying one’s ideological adversaries, so that their bad ideas can be easily called out and debunked.

I don’t agree. The critical difference lies in the fact that words such as “racism,” “violence,” and “trauma” are used to describe specific ideas, whereas terms such as “woke” or “wokeness” are used mainly to describe groups of people or collections of ideas—and this much more easily lends itself to imprecision. Even with linguistic parasitism at play, a label such as “racist” still describes (or purports to describe) a specific idea. “Woke” never worked that way, and it never will.

The “woke” are not a monolith. And the ambiguity of the term, coupled with the stridency of those who weaponize it to score points in arguments, causes a number of negative side effects. Instead of eliciting productive engagement or effective opposition, we get conversations in which no one really knows what anyone else means, and which quickly devolve into barbs and smears. We now spend more time arguing over who is or isn’t “woke,” and what specific beliefs and behaviors can be attributed to anyone who adopts the label or has it thrust upon them, than we do about real-life problems.

It’s important to analyze what we’re actually trying to do when we underscore and address “wokeness.” Are we attempting to mitigate the damage caused by specific ideas, or are we looking to identify, fight, and ultimately defeat some nebulous “them”? We all say we want the former, but all we seem to do is the latter.

When engaging with someone, ask yourself: are you straw-manning or star-manning them? Would they agree with your characterization of who they are and what they think? If you’re hinging your argument on assumptions of what “woke” means, you’re likely missing the target.

The truth is that we don’t need a term to describe “them.” “They” are the wrong target for our attention and criticism to begin with. Whatever side of the argument we’re on, a better approach is to focus on the specific ideas we think are holding society back. Beliefs and behaviors have names that are far less liable to fluctuate from person to person.

Taking this tack also gets you more allies, because many “woke” people disagree with one another on what constitutes a better way forward on a particular issue. Pointing to your concrete disagreements in good faith will be more productive than uttering scathing generalizations about wide swathes of people whom you lump together under a single adjective.