Science / Tech

Deprograming Patriotism

‘The Technological Republic’ is a searching indictment of a culture that has lost sight of its metaphysical horizons and now seeks an escape from history.

A review of The Technological Republic: Hard Power, Soft Belief, and the Future of the West by Alexander Karp and Nicholas W. Zamiska; 320 pages; Bodley Head (February 2025)

In the spring of 2018, America’s leading software company, Google, now known as Alphabet, abruptly stopped work on a project with the US Department of Defence. “Project Maven” was designed to assist the analysis of satellite and other reconnaissance imagery for planning and executing special-forces operations behind enemy lines. But an internal revolt broke out at Google, and employees began protesting the company’s involvement in developing artificial intelligence for military purposes. Thousands of employees, including dozens of senior engineers, signed an open letter to Sundar Pichai, the company’s chief executive, reproaching him for collaborating with the US military. “We believe that Google should not be in the business of war,” it read. Instead of resisting the mob, or trying to enlighten it, Pichai caved in, and Google swiftly terminated its contract with the US government.

This aversion to placing new technology at the service of the US Department of Defence is not uncommon in Silicon Valley, but the libertarian-conservative tech entrepreneur Peter Thiel was incensed. In an article for the New York Times the following year, he heaped scorn on the notion that Google could effectively serve a global marketplace without taking sides in a world of fierce geopolitical competition. Thiel’s argument was convincing. He pointed out that, although it had severed its contract with the US military to thunderous applause from its rank-and-file, Google had recently opened an AI lab in Beijing without a murmur of protest. Since the Chinese Communist Party adheres to the principle of “civil-military fusion,” mandating that all research conducted in China must be shared with the People’s Liberation Army, this meant that Google was content to assist a foreign adversary in the new arms race of artificial intelligence. Thiel concluded that Google was part of a wider “archipelago” of private firms extending from Wall Street to Silicon Valley infected with an “extreme strain of parochialism” that was undercutting the United States in its fight for primacy and, in turn, imperilling liberal civilisation.

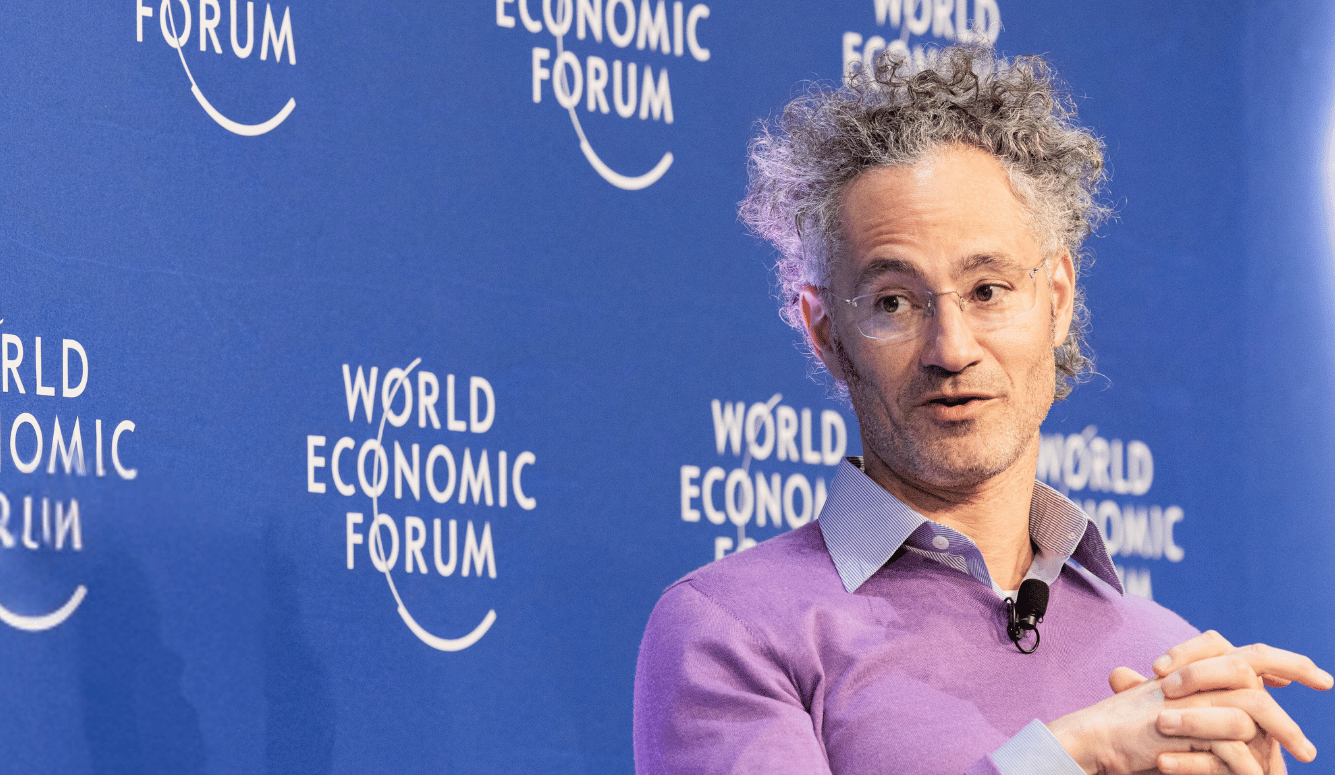

In their book, The Technological Republic, Alexander Karp and Nicholas Zamiska extend and develop this critique. They are dismayed by the entitlement and small-mindedness of Silicon Valley and set out to explain why Big Tech is so important to defending the West and its liberties. Karp is the co-founder and chief executive of Palantir Technologies, and Zamiska is his legal counsel and head of corporate affairs. Together, they make a compelling case that the software industry must renew its commitment to the nation and the world order at a time when both are under several forms of open and covert attack. They argue that civilisation relies on deeper and sturdier values than the cultural agnosticism preached in Silicon Valley, and that in a wicked and dangerous world, American tech should fight for those values.

In their day jobs, the authors have been doing their bit. Since it was founded in 2003, Palantir has been enlisted by the national-security state to help tackle transnational violence and other threats to open societies. Named after the indestructible crystal balls in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Palantir has been the exception to the technocratic elite’s broad disengagement from the affairs of state. But unlike his co-founder Thiel, Alexander Karp is no right-winger. In the past, he has identified as a socialist, and he has a doctorate in neoclassical social theory. He has donated immense sums to the Democratic Party and voted for its candidates against President Trump. His book is as much an intellectual assault on “market triumphalism” as it is an unapologetic plea for the American system. This makes for an unusual combination in today’s polarised landscape, and it commands attention as much for its originality as for its shrewd insight.