Art and Culture

The Art of Not Quite Listening

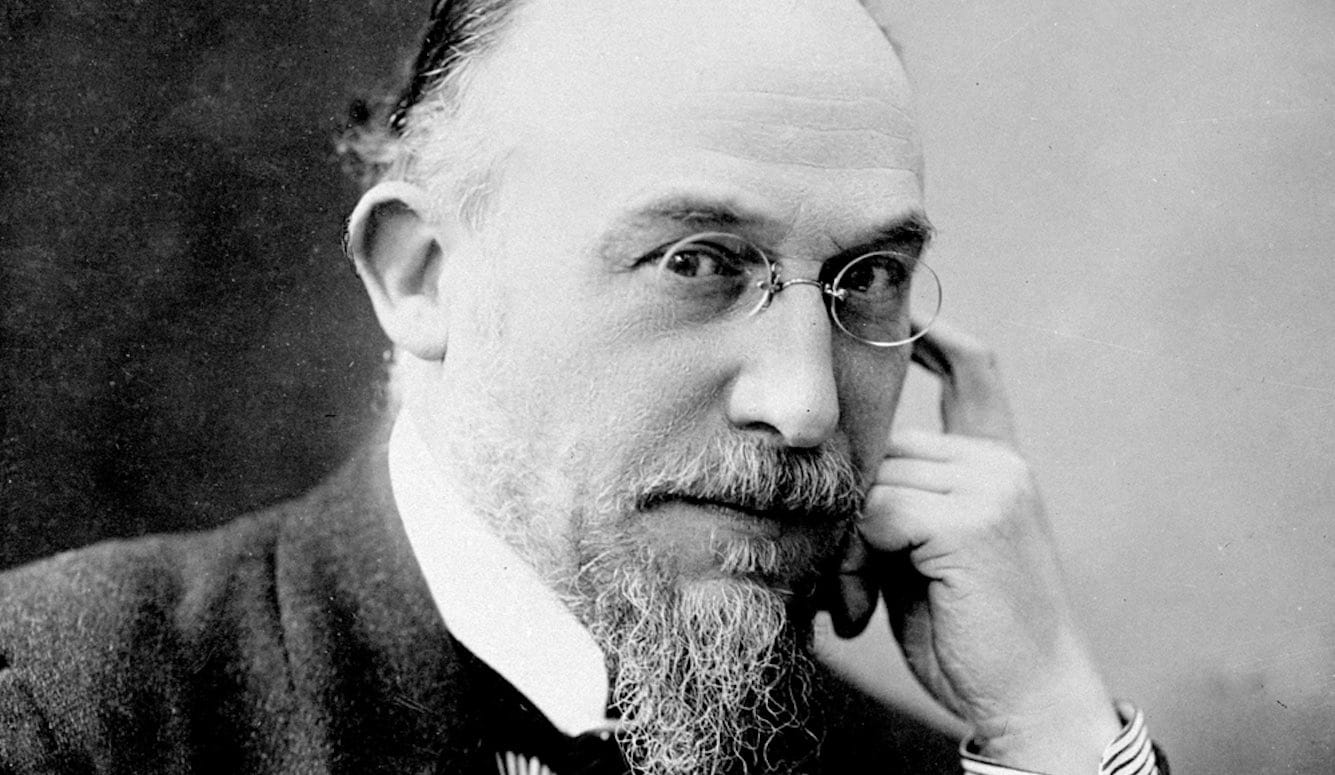

Ian Penman has published an eccentric new book about Erik Satie, a French surrealist composer and celebratory nuisance with a tiny oeuvre and massive influence.

In 1963, the avant-garde musician John Cage performed a work titled “Vexations,” an experimental work written by one of his forebears in 1893. This short work for piano is a kind of atonal sound-screen that seems to lose our interest after just a couple of minutes. And yet, its directionlessness fulfils some yearning in its composer that is part hardship and part joke—the accompanying note instructs its performer(s) to play it 840 times in succession. Cage and a dozen other players took turns at keeping the circling going for its eighteen-hour Manhattan premiere. Eventually, word reached the denizens of Greenwich Village that here was true innovation—a wacky but athletic marathon, exemplary of the 1960s’ new idea of performance art. So, something more than quizzical interest greeted the performance and news of its deviser—the early 20th century’s famously frivolous French composer, Erik Satie.

“Vexations” heralded the rebirth of musical stasis—a sequence of fragmented chord patterns, sans melody, played on long repeat or just once. Of the style’s inertia, Satie remarked that he was mimicking the comforting sameness of one’s couches and end tables, which is why he christened the form musique d’ameublement or “furniture music.” In an interview sixty years later, the American composer Virgil Thomson—who was studying with Nadia Boulanger in Paris during the furniture-music heyday in the 1920s—described the form to me as “music you sit in the presence of.” Today, we know this musical wallpapering as minimalism: music you absorb, endure, neglect, or enjoy by drifting away from it. You may value it because, lacking stickiness, it allows you to do things other than listen to it as it plays. It demands less of its listeners’ attention but it may still mesmerise an audience’s impassivity with the insistence of its repetition.

Satie’s work has often been neglected, but it is receiving renewed recognition today. On 1 July, the 100th anniversary of Satie’s death, Erato records released "Satie: Discoveries," a digital album of 27 short pieces for piano, played by Alexandre Tharaud. These works—songs, waltzes, nocturnes—come from Satie’s early “bistro” period, around 1900. According to the label, they are now being “revealed and published for the first time.” They were cobbled together from the composer’s notebooks after archival research by Satie specialists, the British musicologist James Nye and the Japanese violinist Sato Matsui.

The beautiful surfaces of Satie’s style have also been used for hypnotic effect in recordings by other artists and in TV and movie soundtracks: Brian Eno’s 1979 album Ambient 1: Music for Airports, John Adams’s opera Nixon in China, and the wall of crystalline drones in Ludwig Göransson’s score for Christopher Nolan’s 2023 Oppenheimer biopic. They are perfect for a scene or a collage of scenes in which its repetitious patterns contrast with propulsive or turbulent motion. And its unadorned simplicity can add ballast to psychological and physical panoramas, such as when Max Richter soaks viewers in the fever dream of The Leftovers, when Philip Glass brings ecstatic grandeur to the daredevil surfers in the 100 Foot Wave, or when Ludovico Einaudi underscores the human displacement of Amazon-warehouse vagabonds in Nomadland.

As a miniaturist, Satie loved shaping short tides of repetition, which gave his compositions the brevity and charm of a poem. His economy shines in the evenly stated major ninth and major seventh chords of his “Three Gnossiennes” and “Three Gymnopédies” (adaptations of the first and second movements of the latter would open the quadruple-platinum sophomore album released by Blood, Sweat, and Tears in 1968). Those tender evocations were from Satie’s early period, 1884 to 1904, penned during his twenties and thirties. “Vexations,” “Three Pieces in Pear Form,” “Nose Cones,”“Genuine Flabby Preludes,” and a few other arch titles require very little virtuosity, avoid passionate squalls, and speak with mock-heroic bluster or exotic frivolity. According to Roger Shattuck in The Banquet Years—the first cultural history of the French fin de siècle avant-garde, published in 1955—these works capture a “music that seems to move at a standstill.” Satie instructed his gaily lit café patrons to only half-listen to him play, since their conversations were part of the bar’s furnishings.

Satie’s closest friend Claude Debussy said he was a medievalist, born four centuries after the era to which he belonged. Others agreed. His pianistic apéritifs only really caught the interest of other composers, and Satie, who was temperamentally lazy, earned little from his regular gigs in Montmartre bistros. (His audience was only half-listening, after all.) His flat was unheated and had no running water. He was called an “amateur bungler,” an indolent, and a sideshow. In the end, the lack of recognition (and too much cognac) got to him. At the age of forty, he declared, “I’m dying of boredom,” and enrolled in the Schola Cantorum to study composition, counterpoint, and orchestration right. When I was in music school, my theory teacher said that Satie, who graduated in three years (as I did), kept much of his nonchalance in his scores, except he added a lot of chromatic notes where they were not needed.

Satie was a dandy, nicknamed the Velvet Gentleman for owning seven identical chestnut-coloured corduroy suits. Most days, he would walk the six miles from his home to cabaret wearing a bowler hat and a pince-nez and carrying an umbrella. Around 1915, at the start of his final decade, he was rediscovered by the hyper-hip Parisians, who were delighted to find that he was still living among them. The cubist phenomenologists and André Breton welcomed this musical aristocrat and adopted his aesthetic, valorising lightness, irony, assemblage, and adopting a penchant for vertical sonorities that disdained colour and harmony. Alex Ross called the Satie effect, “the instant prolonged,” which meant that his tunes were more like lakes than rivers.

After the First World War ended, dancers, playwrights, and producers lined up to collaborate with him. The result was a series of ballets involving Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Leon Massine, Sergei Diaghilev, Blaise Cendrars, André Derain, and others. In one of these, the parodic set-design drama Parade, a cheeky scrim of fairground rinky-dink was scored for the sound of gunshots, typewriting clacks, and slide whistles. Satie’s 1924 swan song, Relâche—the title of which translates as “Tonight’s concert is cancelled”—erupted in argument, with the stiff- and loose-collared factions of the audience slapping one another with their leather gloves. The painter Francis Picabia, who designed the décor and costumes for Relâche, said the plotless spectacle “represented life with no tomorrow, life of today. Car headlights, pearl necklaces, advertising, music, men in evening dress, movement, noise, and play.”

When Satie died of cirrhosis of the liver, a hundred years ago this month at the age of 59, he could not have known that his quixotic, surrealist, and bricolage eccentricities would wellspring the century’s affair with minimalism and turn its anti-conventionality into one of the most conventional and copied of all musical forms. And yet, for a hundred years, minimalism has rearranged the content of art—in painting (Piet Mondrian), tape loops (Steve Reich), film scores (Hans Zimmer), gamelan orchestras (Lou Harrison), Nordic soundscapes (John Luther Adams), angelic pop (Sigur Rós), and the sampling of rap and hip-hop.

To trace Satie’s legacy into our age of PoMo compilations comes a writer who adores Satie’s tiny oeuvre and massive influence—Ian Penman and his whimsically ephemeral meditation, Erik Satie Three Piece Suite. Penman is a maven of cross-generational pop, rock, and punk, who has spent years writing deft music criticism for publications like City Journal, NME, and the London Review of Books, some of which is collected in his 2019 anthology It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track. His 2023 tribute to filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, subtitled Thousands of Mirrors, shows off an encyclopaedist’s obsession with random order. In his survey of the under-appreciated and somewhat cranky narcissist of 1970s New German Cinema, Penman explores his mystique in 450 takes, each of which is between a sentence and a paragraph long, leaping from one thing to another. These postcard thoughts accumulate like Fassbinder’s own diet of sausages, cabbage, cocaine, and barbiturates, which killed him at the age of 37 after he’d already written and directed (and occasionally acted in) 44 films and some TV work.

Erik Satie is more clearly and decisively thought out. Penman’s three-piece suite—“Satie Essay,” “Satie A to Z,” and “Satie Diary”—alludes to a set of tempo-shifting dance pieces and offers a range of angles and repose. The opening essay brings the composer’s dandyish peculiarities to life, and as Penman tries to sort the role Satie played from the artist, he finds them deviously intertwined. The A to Z section—which consumes about half this short book—catalogues friends and lovers, concepts like furniture music and the number three, microtones, and objects of relevance like his umbrella. For example, there are four terse entries for NOTE:

- A “written symbol” of tone and duration on a musical staff.

- A record of something worth recording.

- Satie’s constant jottings of tunes and ideas as he walked.

- And, fun fact, the words “note” and tone” consist of the same four

letters!

Elsewhere in this section, you can find Penman appraising happiness, haunting, and hoarding, each of which was a key reoccurrence in Satie’s life.

The closing diary portion quotes from two years of the author’s morning ruminations on what he’s thinking about, listening to, or improvising at the piano. He overhears Satie sitting in a booth behind him or strolling with friends through the gardens of French expressionism. His widening gyre spans Satie’s heyday as well as the avant-garde impudence that still nags at our time. This section also displays the sparks of Penman’s obsession—years spent buying books and records from charity shops; time lost in the modern recordings of Satie, Maurice Ravel, Debussy, and Bill Evans—listening full-eared to pianists like Thelonious Monk, Harold Budd, Morton Feldman, he writes, “is to feel your sense of time being shifted sideways, decomposed, rearranged.” Pieces of dreams he can barely remember recall Satie’s ghosts; he rewatches David Lynch films and rereads Ravel, Thomas Bernhard, Roland Barthes. At one point, Penman drops in this little nugget, which serves as the book’s summa cum laude: “Some of Satie’s better known piano pieces are like preambles or prefaces, but absent the feeling of anything to follow.” Terry Riley, the composer of In C and A Rainbow in Curved Air, agreed: Music need not progress to be interesting.

Penman does not follow the conventional biographical chronology of this followed by that. He delays a potted summary of Satie’s life for fourteen pages and begins, instead, with a 1924 short film of Satie and the influential surrealists Picabia and René Clair, mugging like the early Beatles before a movie camera. The footage shows that Satie, then 58 and an OG merry prankster, loved any stage on which he could perform. Penman does not wish to portray Satie as a tubercular bohemian; he sees him as a celebratory nuisance. He was an example to outsiders-to-come who mixed “the funny-sinister and fantasy-grotesque” like John Cage, William Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut, Eileen Myles, and countless fellow travellers whose quirks would become their schtick.

Penman argues that Satie was indigenous to music, like a mystic without precedent. He created “his own exact and proper forms ... little musical sigils and spells that in effect proclaim: in order to be mystical, you don’t have to be symphonic.” Unlike Gustav Mahler’s mighty Germanic dramas, Satie’s ear was trained on the small things of the world, the delighted in and disposed of, that “more convincingly evoke a feeling of sacredness.”

With Satie, it is always a matter of form. Imbuing set forms—nocturne, prelude, waltz—with an inimitable personal touch. He takes a classic form and squints at it, walks around it, flutters away the dust. (It is a bit like Picasso taking Las Meninas by Velázquez and making it anew.)

In retrospect, Satie’s radical approach was like a feathery counterweight to the Wagnerian hysteria that swept European music and nurtured Nietzschean ideology. His music “doesn’t rely on dramatic development or expressive gestures.” Furniture music is “pure sound, tone and spatial awareness, with no separation of background and foreground. A new kind of listening—or not quite listening—space.”

Penman calls Satie’s “method” the art of displacement—the half-heard and the barely noticed, as conceptual as it is real. The music is meant to evaporate, and its impermanence is its experience and point. Performing Satie is a way of abutting the grandiosity of performance itself, for his lean-to has collapsed before we can really use it. What’s more, Satie values ordinariness, the Cageian sound context in which music and life are scored to interact, and the more overlap there is, the better. As Satie seduces you with his brevity, that very brevity liberates you of any romantic yearning for more.

Illustrative of this view are Satie’s three carnivalesque pieces “Desiccated Embryos,” in which he steals two themes from Frédéric Chopin and goes a bit mental with his playing instructions: “Walk a bit. Going out in the morning. It’s raining. The sun is behind clouds. Pretty cold. All right.” And there’s this bit of advice: “[Play] like a nightingale with a toothache.” To confound the beard-stroking mischief, he adds, “this work is absolutely incomprehensible, even to me.”