Art and Culture

Purity, Profit, and Politics

How journalism exchanged the duty to inform for an ethic of customer satisfaction.

A full audio version of this article can be found below the paywall.

The Balkanisation of Mass Media

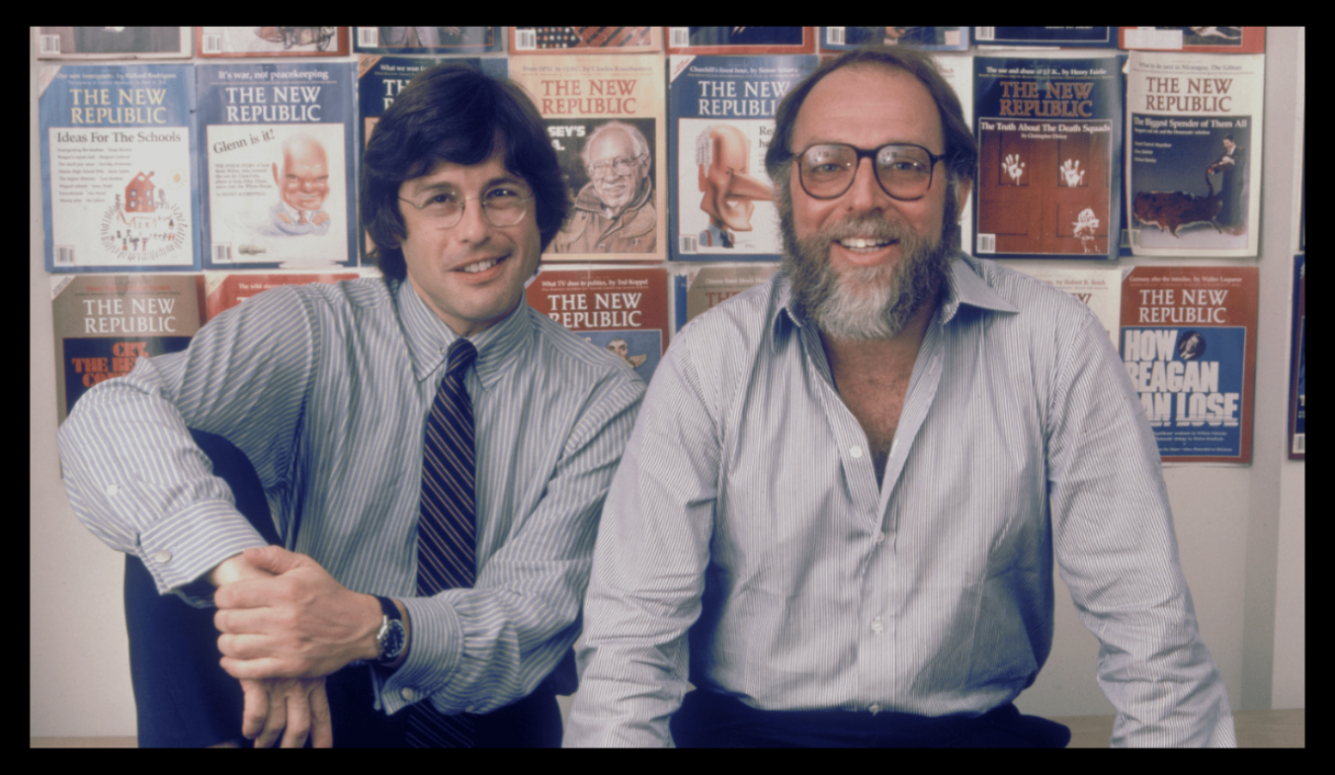

After I stumbled into a writing career in late 1981, placing an unsolicited piece in Harper’s, I had the good fortune to be taken under the wing of Lewis Lapham and Michael Kinsley, then two of the titans of the magazine world. I was privy to story meetings where the staple question was, “What do our readers need to know in order to be well-rounded, intellectually confident individuals who can compete in the marketplace of ideas?” However, that noble ethic was already under assault in magazines and the wider world of media.

Earlier that same year, the venerable Walter Cronkite had retired from two decades at the helm of CBS News’ nightly broadcast. By the midpoint of his tenure, the phrase “the most trusted man in America” was used to describe Cronkite so often that it had almost become part of his name. (Query the phrase; you’ll be besieged with pages of references to Cronkite.) He did for television news what Edward R. Murrow’s “just the facts” approach had done for radio beginning in the 1930s. Other news anchors of the era—NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report and Nightline’s Ted Koppel a bit later—were held in similar esteem.

Cronkite’s laconic sign-off said it all: “And that’s the way it is.” Like Lapham and Kinsley (and editors at other top general-interest publications), Cronkite saw himself as something of an oracle, distilling America’s multifarious milestones and mishaps down to the most significant events that could be crammed into thirty minutes’ worth of commercial air-time. Cronkite’s retirement was not just the loss of an institution in American journalism, it also presaged the loss of the institution of American journalism as it was then understood.

Historically, the imparting of news was a one-way, top-down process. The keepers of this loose-knit kingdom were vested with the right and responsibility to curate a consensus trove of necessary information to be communicated to the masses. Today, the ethic that drove such men and their media organisations is all but gone. Publications and networks alike now set aside tidy sums for focus groups, marketing consultants, and algorithmic formulas designed to ascertain what readers want to know so that it can be provided to them. This attitude is very different in its implications from the one that prevailed at those long-ago story meetings and it is apt to yield wholly different content. (Light fare about the Royals, fodder for vehement Trump supporters or opponents, service pieces about successful loft living or—on the same day in The New York Times—storing your winter clothes and how to avoid looking like a MAGA woman).

A byproduct of this intense focus on customer demand is that the world of media has splintered. Pew may be understating the case when it describes a “fragmented media environment with seemingly endless sources of information to choose from.” Pew, which focuses chiefly on established alternative media, lists 105 digital news sites boasting some 27 million unique monthly visitors. Media watchdog Ad Fontes is more comprehensive, tallying 3,600 news sources, 700 informational podcasts, and 474 video/TV programs. This gibes with American University’s database of some 4,500 such outlets. These highly nichified offerings encompass myriad mission statements and takes on the news of the day.

Further, with 86 percent of Americans getting at least some of their news from sources available on hand-held devices (including, God help us, TikTok), modern media lean more heavily on their online arms and let the algorithms supplant news judgment. This not only exposes more of us to the social-media clickbait outrage machine—which widens all schisms—but it also has the effect of nudging important but anodyne news (say, a major mortgage lender changing its system of credit scoring) aside to make room for the latest Taylor Swift break-up or #MeToo allegation. And for the record, even the most reputable news sources are resorting to clickbait nowadays. (See also here.)

As a result of media variety, contemporary America may lead the Western world in producing one-dimensional adults who haven’t a clue what’s going on.

The micro-targeting of consumer interests has also led to a proliferation of compartmentalised magazines and online journals that cater to interests and “identity” in all its permutations—a far cry from the heyday of the heralded general-interest magazines that kick-started water-cooler conversations for the next week. A reader who cares only about equestrian matters can read Equus or Horse Illustrated and never need ponder whether academic freedom has gone too far. If you desire nothing but content that’s of interest to blacks (or at least that’s bracketed as such) you can read Ebony or Black Enterprise or Jet or The Crisis or The Source or Vibe or... If you are a dark-skinned black woman or girl, you can enjoy DDS (Divine Dark Skin), which published a few print issues in 2019 and is now online-only. If you are a dwarf, there’s LPA Today, the official publication of “little people of America.” The Cord is for paraplegics. There’s no major magazine for non-neurotypical lesbians, but there’s a book, Queerly Autistic. As Chris Cuomo informed his NewsNation audience on 2 June, “Our media doesn’t play to the majority, it plays to the pockets of fringe interests. It plays small-ball.”

As a result of all this variety, contemporary America may lead the Western world in producing one-dimensional adults who haven’t a clue what’s going on—or, at least, who don’t know many of the things they should know. Here’s a Ted Talk and a sampling of articles (mostly in publications that would be considered fairly literate by today’s standards) lamenting the basic ignorance of everyday Americans:

- Public Square: “Knowing Less than We Think”

- Huffington Post: “The Price America Pays for Ignorant Americans”

- Current: “Public Media Is Failing in its Mission to Inform and Educate”

- Business Insider: “Survey Reveals 12 Things People Don’t Know About Their Own Country”

- Johns Hopkins report: “Americans Don’t Know Much About State Government, Survey Shows”

- Forbes: “The Ignorant Voter”

- Saturday Evening Post: “Should the Uninformed Be Allowed to Vote?”

- Mother Jones: “America is the Developed World’s Second Most Ignorant Country”

- Investigative Post: “Americans Are Horribly Informed on the Economy”

- Seattle Times: “We’re at the Mercy of an Uninformed Electorate”

Perhaps even more troubling than the informational balkanisation is the sociopolitical skew that so many forms of modern media embrace when they court (or pander to?) their audiences. This approach prevents certain topics, or key nuances thereof, from being covered. During Cronkite’s reign, the criteria undergirding news judgment were more or less objective and universal: The lead story on a given day was the most important thing that happened that day. (There is always some subjectivity involved, but it tells us something that most days, the so-called Big Three network newscasts had the same two stories in first or second position.) Today, the lead story is the most important event that serves another goal as well—ensuring audience loyalty.

All of which reinforces silo thinking and today’s reflexive and uncompromising tribalism. Fragmented journalism competing for consumer eyeballs breeds fragmented thinking and a fragmented view of life in America. As freelance journalist Matt Yglesias has written, “One consequence of this competition is that it’s now much harder to manufacture consent.” If there are no consensus buckets of information—no news or background knowledge that we expect everyone to know and trust—there is no consensus reality. We are left with a world of competing personal truths, where Americans cannot fathom why other segments of media are serving up something different to their own. This may explain why trust in journalism is now at an all-time low.

The story of how we got to this state of affairs is a tragicomedy in three acts.

Act I: The 60 Minutes Effect

While it’s reckless to reduce broad cultural events to single-factor causation, the arrival of 60 Minutes in September 1968 does seem to have precipitated journalism’s shift away from its traditional, top-down model of content delivery. One might say the road to media hell was paved with the good intentions of the most esteemed news show ever produced. Prior to that show’s debut, entertainment companies regarded their news divisions as loss leaders, an activity they undertook as a public service. Profits were neither demanded nor expected. If audiences liked what they were doing, that was a bonus.

60 Minutes changed all that. Though it took a few years and a new time slot for the show to find its feet, it demonstrated that prime-time news could be a massive revenue generator. Based on ratings, 60 Minutes is the most successful program in American television history, certainly since it was moved into its present Sunday slot in 1975. It would go on to become a top-ten show each year between 1977 and 2000, and the top-rated news show for a remarkable half-century. As of the fall of 2024, the show had ranked top in the coveted 25–54 demographic for 21 consecutive seasons—an unparalleled achievement.

As Bernard Goldberg explains in his eye-opening 2001 book, Bias, once 60 Minutes made clear that news shows could contribute to the corporate bottom line, the strategists began requiring them to do so. They then set about finding improved ways of satisfying that mandate. News divisions lost their sovereignty and became increasingly answerable to corporate bean-counters. Network execs, who had previously ignored their news divisions, began brainstorming ways to capture and hold an audience and sell advertisers on the plan. The 60 Minutes effect metastasised throughout news media, not only spawning clones (Dateline, 48 Hours, 20/20, Primetime) but inspiring innumerable adaptations in news delivery. News was no longer solely about news judgment. Newsroom habitués began using words like “eyeballs” and asking whether a given story “pulled” or “got the numbers.” Purity had given way to profit.

Here, a second emergent genre would have a ripple effect on news: the made-for-TV movie craze, which reached its zenith with the true-crime explosion of the late 1980s and ’90s. The ratings for these two-hour excursions into the twisted and the tawdry (which, full disclosure, included an adaptation of one of my books) caught the eye of network programmers, and crime became the staple content of the news magazines. Even staid 60 Minutes embraced its share of mayhem and melodrama (albeit at a somewhat more high-brow level). If it bleeds it leads morphed into if it bleeds we’ll make a full-length show out of it. Special “news” features were constructed around JonBenét Ramsey and Madeleine McCann and Jaycee Dugard and Elizabeth Smart and Jodi Arias and “tot mom” Casey Anthony and the “DC Sniper.” Why, after all, spend all that time (in prime time, no less) trying to demystify some arcane piece of legislation when you can give viewers frantic 911 calls and brain matter splattered along baseboards? In this way, news divisions entered the era of trauma porn.

Regular news shows began constructing five- or ten-minute segments around sensational crimes, especially after O.J. Simpson’s arrest and trial became a ratings bonanza. This same impetus led to the catastrophising of, well, pretty much everything. Every hurricane was forecast to be a would-be Andrew (until Andrew was dethroned by Katrina); every plane crash signified unsafe skies; every outbreak became the potentially apocalyptic disease of the month; every climate scientist since 1972 who predicted extinction within ten years was given an uncritical platform.

At the local level, meanwhile, market testing gave us two other phenomena:

- So-called “happy news,” wherein smiling, bantering anchors told viewers about the latest motorcyclist tragically decapitated.

- The weather-babe revolution, wherein news of stationary and occluded fronts was no longer delivered by greying gentlemen in bow-ties but by winsome lasses in tight skirts whose ample fronts were neither occluded nor stationary.

If your news division is subject to profit and loss considerations and the expectation of showing a healthy bottom line, you also become subject to some form of the programming considerations that gave us Cops and Jersey Shore.

Act II: Audience-Driven News

No conceptual development had a more seismic impact on the news business over the past few decades than the notion of “centring” content on the audience. In this model, the audience would have input into what it reads, sees, or hears from the news media. Today, audiences dictate their informational preferences as well as how they want that material delivered and contextualised and by whom. (Prospective on-air hires are Q-tested to ensure that they vibe properly with audiences.) Even the media elite function more like waitstaff in some variegated informational cafeteria, bringing customised “content” to their audiences, seasoned to taste.

Some of this is a byproduct of the changing American social contract as we move through the new millennium. By every measure, narcissism and self-interest are at all-time highs. Consumers expect their needs to be met and they want a say in all deliverables, tangible and intangible alike. In her provocatively titled essay, “A Serious Problem the News Industry Does not Talk About,” media consultant Jennifer Brandel puts it like this:

We recognize that the world is no longer top-down. We want to help newsrooms recognize that, too. We’re focused on evolving new models and tools for newsrooms to partner with the incredible people in their communities, rather than toss content down at them from the mountaintop, hoping they’ll like it, share it, come back for more and maybe one day pay for it if we need them to (by asking nicely or threatening to shut it off). Thing is, there is no mountaintop anymore. Newsrooms no longer have a lock on the information people need and want to live their lives.

But Brandel is wrong to say that no one is talking about this. Even Editor & Publisher, known for its stodgy reverence for industry orthodoxies, recently ran a piece about “data-driven strategies” for better capturing local news consumers. “As the digital age reshapes the media landscape,” the trade monthly observes, “local news publishers face a crucial challenge: staying relevant and profitable.” Audience engagement is a prominent topic at the Columbia Journalism Review as well, which clearly conceives relevance as a key to the survival of embattled legacy journalism. (You’ll note the recurrent theme of relevance, a concept that crops up ten times in the CJR piece and is ubiquitous elsewhere in contemporary media circles; it is a genteel euphemism for kowtowing to the end-user.) As CJR’s author notes:

As much as journalists like to talk about the five W’s of a news story—who, what, where, when, and why—the practice of journalism rests on three other, equally important questions. Who am I writing for? Why is it important for them to read it? And what will they find interesting?

The desire to ensnare the viewing/reading public isn’t brand-new, of course. Circulation was at the heart of the bitter feud between William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer (which spawned the former’s “yellow journalism”). But the circulation goals acquired far greater urgency across the board after mass-media news divisions were brought under corporate umbrellas post-60 Minutes, and the early debates that ensued were more concerned with tone than content.

Advantage-seeking news management brought in sociologists who argued that the news business basically consisted of a bunch of overeducated elites mostly talking to (a) each other and (b) a small core of urban sophisticates. Changes were therefore needed to reach the unwashed masses. The experts were “baffled,” reports CJR, “that broadcasters felt they were providing public service with newscasts that appealed only to the 25% of viewers with college degrees.” Even though efforts were made to entice Joe Lunchbucket (usually with a dumbed-down lexicon and/or embarrassingly lurid crime coverage), the news still remained mostly the news—a top-down recitation of what editors thought informed citizens needed to know:

Now new tools can help them solicit readers’ feedback, analyze and understand readers’ behavior, and open new channels for conversation. These new capabilities promise to shine a light on the abstract audience—making one’s readers present, quantified and real.

Rachel Mersey, a former journalist for the Arizona Republic and now an assistant professor at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, puts it this way in her gloomy book, Can Journalism Be Saved?: “Journalists are no longer in a relationship with their audience built on one-way communications as Murrow, Lippmann, and Woodward and Bernstein were.” The interactive connection with the audience is today an integral part of news programming—and must be, in her view, in order to answer her book’s titular question with a resounding “Yes.” Mersey continues, “So the real market model of journalism for serious producers of news is figuring out how to tell important stories in relevant and compelling ways with products that are sensitive to users’ changing needs.”

Even if newsrooms aren’t able to diagnose the audience’s desires with the precision of an MRI, reports Slate, they’re expending a ton of time and resources trying to do so. Major news outlets employ advanced tech to develop metrics that allow them to tailor programming in ways unrelated to news judgment as the Murrows and Cronkites understood it. They also employ “audience teams,” whose job is to keep their fingers on the erratic pulse of the consuming public. Media columnist Amalie Nash describes that work as follows:

Audience teams, especially initially, were often thought of as a service desk: They’re the ones who optimise a story with links, add a search-friendly headline and chatter, and distribute that story across social channels and the homepage. ... But the audience team is at the core of any successful newsroom. They understand readers and trends, they have expertise on data, they’re key to the organisation’s off-platform strategy, and so much more. Without an effective audience team, it’s hard to know what your readers want and how to reach them.

According to Nash, units like these guided the New York Times and the Washington Post through their 2024 election coverage. Final data on 2024 press coverage are not yet in, but in the 2020 election, CJR reported in an earlier piece, “reporters and media organizations rallied behind Clinton’s candidacy (and against Trump’s) in a manner that was unlike any other contemporary election cycle.” Not coincidentally, so did the staple audiences of the Post and Times.

But should news be democratised in this way? Should it be developed and test-marketed like jeans or yoghurt, where consumer preferences are paramount? Apart from politicisation—which we’ll get to in Act III—too many news broadcasts informed by such imperatives begin to resemble celebrity gossip sites like TMZ (as evidenced by today’s wall-to-wall coverage of the Diddy trial, and before that, the Jeffrey Epstein and Johnny Depp spectacles). They also tend to devolve into alarmism, as surveys reveal that the most faithful news consumers are the inveterate “doomscrollers” who like to feel that they’re on the cutting edge of the next great threat or conspiracy or political/financial scheme to come down the pike.

Pleasing the audience may be driving it crazy.

Apart from mis/disinforming the general public, the endless stream of ugliness to which the doomscrollers are addicted does them real harm. This is obviously a chicken/egg peculiarity, but the end result is pretty far from happy news for all those obsessive addicts. Pleasing the audience may be driving it crazy. “American media [is] not just exciting—it’s oftentimes pretty negative, the news that we’re getting,” explains health journalist Kristen Meinzer in a Mayo Clinic panel discussion titled “How the News Rewires Your Brain.” (Spoiler: It’s not good.) “Because that’s what the news outlets have learned people will click on. People will go back again and again to those dangerous headlines, those scary disasters, this alarming crime statistic, this economic crash that’s about to happen.”

The worst news may be for the very demographic media do-gooders aspire to help: black Americans. For doomscrolling blacks, rewatching endless replays of George Floyd’s death or some other horrific (but statistically rare) incident can trigger an abiding paranoia and an exaggerated sense of how pressing the threat is. As NBC news reports, “The video of Floyd’s last gasps for air was everywhere, for better or for worse, said Maryam Jernigan-Noesi, a psychologist who studies racial trauma. Watching situations like that can bring up past trauma for people of color.” A New York Times article does a good job of documenting black psychological unease but, in typical media fashion, omits journalism’s own role in inflating the prevalence of Floyd-type killings.

Notwithstanding these issues, industry pushback against audience-driven news is minimal. CJR pays lip service to the notion that “journalists ... are wary of allowing readers to dictate what is newsworthy,” but then drops that theme and joins E&P in averring that success today “is about making data-driven decisions that align with what consumers want and what advertisers need.” So, in this new media world, decision-makers must appease not only consumers but advertisers as well. And the admission comes from one of the most orthodox voices in the business.

Act III: The Partisan Imperative

Volumes have been written about the regrettable bias and tribalism of latter-day newsrooms, but it bears noting here that audience-farming was not the original impetus for today’s supercharged media polarity. As explained in Goldberg’s Bias, and later in Mark Levin’s Unfreedom of the Press, media tribalism began as a strong leftward spin produced by the political inclinations of journalists themselves. The explosion of the New Journalism in the 1960s gave print journalists unprecedented licence to interpret life through their own lenses. Young journalists graduating from the nation’s citadels of media education (where liberal faculty outnumbered their right-wing counterparts twenty-to-one by the late-2010s) felt a sense of collective purpose that entitled them to act as a “force for good” (according to their own definition of good, of course).

Then came the backlash: The Rush Limbaugh revolution and the ascendancy of right-wing radio, which begat a zillion conservative talk-shows and then Fox News in October 1996. The media version of Gettysburg began in earnest. Competition for market share became not just fierce but nasty, featuring relentless assaults on the legitimacy of competitors. From the 1988 inception of his pioneering radio show, Limbaugh delighted listeners by attacking the network and cable-news establishment as a malevolent, subversive monolith that controlled the airwaves (even though by the mid-’90s Limbaugh’s reach far exceeded that of the cable channels he excoriated). Of the emergence of right-wing radio, Matt Yglesias has written:

This burgeoning conservative broadcast empire developed the habit of referring to “the media” as an entity that did not include itself, even though conservative talk—unlike alt weeklies or small circulation magazines—had essentially unlimited distribution. The distinction between Rush Limbaugh and “the media” was sociological and ideological, not really about technology or reach.

This malady soon spread to television/cable news. Whereas it was once considered declassé for TV media elites to bad-mouth each other’s reportage (except in whispered asides to favoured media critics), the mutual sniping was now unfolding right on-air in mid-broadcast. (Nor, in fairness, was it just Right versus Left; even the normally left-leaning networks and cable stations would also exploit competitors’ slip-ups.) Of this free-for-all, Yglesias observes, “Every participant in the [news business] has a strong incentive to exaggerate how bad ‘the media’ is in order to sell their own wares.”

As the politically encamped media cultivated a deepening partisan bond with their audiences, their pet phrases seeped into the American lexicon, with Limbaugh acolytes denouncing the “drive-by media” and its pitches to “low-information voters,” and Rachel Maddow fans parodying Fox News’ original slogan by labelling the network “unfair and unbalanced.” Regardless of platform, an unholy alliance between journalist and consumer today prevents objective information from getting out and shapes perverse coverage of even innocuous topics like Melania Trump’s wardrobe or Michelle Obama’s hairdo.

Media are preoccupied with sustaining brand loyalty, and the pressure to stay on- message is unrelenting. Reporters who “go rogue” may be blacklisted, as Wall Street Journal contributor Abigail Shrier learned first-hand after publishing a book, Irreversible Damage, critical of the trans juggernaut. The New York Times, with one of the most steadfastly Democrat-voting readerships in the industry, never wavers in its focus, and seems congenitally incapable of writing a headline about Trump that doesn’t throw shade on the president. MSNBC and CNN are wholly credulous in reporting Democratic talking points and wholly sceptical in reporting on the GOP. The inverse is true over at Fox and Newsmax.

Self-appointed media watchdog AllSides states bluntly, “Traditional journalistic standards of objectivity, fairness, and balance have largely gone by the wayside in the American press.” This shift is unapologetic, with news outlets unflinchingly serving their parochial audiences. And so, an enterprise that was once about empowering an informed citizenry by furnishing pertinent facts is now about furnishing selected facts designed to empower right- or left-wing militancy.

The disjunction in worldview can be absurd. On Saturday 24 May, Donald Trump delivered a commencement address at West Point. Fox and Newsmax hailed the patriotism of the speech, notably his extensive homage to the military, while MSNBC and CNN highlighted Trump’s bloviating about DEI or being “persecuted” by the “very bad people” in American society. Depending on which news outlet you watched, you heard two very different speeches. (Such is the symbiotic relationship between those networks and their respective core viewers.) Viewers of competing cable networks therefore see two completely different versions of America. Sadly, that may be just how they like it. Left or right, they enjoy feeling “in the know” and privy to subtleties that elude their low-information opponents. Some surveys even suggest that a newsroom that plays it straight may end up pleasing no one.

Epilogue: And the Brand Played On

On Tuesday, 29 May 2018, a story broke that had everything: death (and plenty of it), overtones of political cover-ups, a direct link to climate change and Mother Nature’s wrath (a favoured theme in today’s newsrooms), and even the media’s favourite theme of all: the embarrassment of President Donald Trump. Late the previous day, Harvard had released a study of Hurricane Maria, which had ravaged Puerto Rico in September 2017 with sustained winds of 155 mph. The new study found that the death toll on the offshore US territory may have exceeded 4,500—some seventy times the original reported total of just 64, which Trump had all but shrugged off when Maria hit.

With this embarrassment of riches on offer, CNN’s headline ought to have written itself. Except that, the day before, Roseanne Barr had tweeted something. On the Monday, Barr had taken a tasteless swipe at former Obama adviser Valerie Jarrett on Twitter. Many people decided the tweet was racist, and in the years between Trayvon Martin and the endless summer of George Floyd, nothing preoccupied the American media quite like the problem of “everyday racism” (as MSNBC would call it during a town hall held the day after Barr sent her tweet).

And so, that Tuesday night on CNN, the hurricane story was mostly relegated to a chryon (plus a few grim photos displayed as the station went to break), while pundits on all major networks and cable outlets spent hours fretting over Roseanne’s antics. It would stay that way for days. Black anchors and commentators recounted their own experiences of racism while Fox hosts felt compelled to highlight incidents in which black people had belittled or abused whites. Throughout American media, the hurricane report and its 4,500-plus deaths were covered only as time permitted between deconstructions of an actress’s tweet.

But at least those two events actually happened. That was not the case with 2019’s Jussie Smollett affair, when a sympathetic media ran with the black actor’s account of being attacked by MAGA thugs despite the story’s obvious red flags. A couple of weeks earlier, the media made hay out of “the smirk” on the face of sixteen-year-old Nicholas Sandmann of Covington Catholic High School during a confrontation with a Native American elder at the Lincoln Memorial. The media took such defamatory liberties in framing Sandmann as the face of white-supremacist contempt that he ended up collecting US$275 million from CNN and an undisclosed sum from the Washington Post. Even that was nothing compared to the dishonesty of the marquee prime-time hosts at Fox in the ensuing years, who promoted charges of election tampering they knew to be false. Fox later agreed to pay a jaw-dropping US$787 million to Dominion Voting Systems, for implying that the company had rigged its machines to hand the 2020 presidential election to Joe Biden.

In the light of which, two questions (the first largely rhetorical) suggest themselves:

- If journalism selectively edits and even invents news in order to build and hold an audience, then spins that news to solidify a sense of allyship with its audience by validating their confirmation bias... is it still journalism?

- Is there visible light at the end of this tunnel?

Well, the availability of 4,500 news outlets appears to give serious-minded consumers an ample array of media to sample in their search for capital-t Truth. But a broad sampling of media, each part of which invokes its own self-serving criteria, yields something closer to a dizzying hologram of American life.

As independent YouTubers or Substackers develop a following, they too tend to play to the algorithms and the demands of their subscribers. More engagement equals more royalties and, well, people gotta eat.

Some observers believe that independent (or “citizen”) journalism provides a preferable alternative to the mainstream broadcast media and press. But how can the work-product avoid being myopic when you have one individual or a small cadre of like-minded individuals framing the news of the day? It is absurd to expect less subjectivity from someone wearing the hats of reporter, news director, writer, editor, and commentator. Moreover, such journalism is notoriously subject to hasty generalisations and the availability heuristic, wherein the journalist assumes that because he witnessed something and/or recalls a similar incident, that phenomenon must be significant and widespread. In addition, as independent YouTubers or Substackers develop a following, they too tend to play to the algorithms and the demands of their subscribers. More engagement equals more royalties and, well, people gotta eat.

One of the more interesting ideas for improving journalism entails the use of artificial intelligence. For the record, AI is almost universally reviled by newsroom rank-and-file because it usurps the writer’s hand and it is sure to cost jobs. That said, theoretically, AI can be programmed to pick news stories based on classically acknowledged criteria and render them without spin. AI can be tasked with making unemotional decisions about the most important stories. On the other hand, humans program AI, and the responses to questions fed into ChatGPT or Grok are hardly dry, toneless recitations of fact. AI has come under almost as much fire for being “woke” (also here) as any mass-media outlet.

This much is certain: whether or not anyone wants it, the public desperately needs information in its purest state, with lead items chosen for their gravity and any connecting of dots done without regard for considerations extrinsic to proper journalism. The costs of abdicating that mission have already been incalculable for both society and journalism itself.

I have given nearly a half-century of my life to journalism as either practitioner or professor; I just retired from the latter activity this past semester. Through most of it, I managed to sustain the passion incubated when my father sat me on his lap at the age of six or seven and began reading to me every night from the three New York dailies he took. In recent years, though, I worried that I was doing my students—particularly writers—a disservice by preparing them for a craft that no longer existed. I’d look at the rapidly fracturing marketplace and I’d feel haunted by the fear that I was putting them on a road to nowhere. As Politico predicted in a bleak January 2024 essay titled “The News Business Really Is Cratering”:

Journalism will survive, of course, even if the business falters as the advertising subsidy that made it viable erodes. Publications for readers who depend on market-moving news like you find in the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg News and other business titles will endure. So will the aforementioned New York Times, which provides news that moves political markets and has established itself as a national voice worth paying for. So, too, will the gossip and lifestyle magazines remain, as will publications like the New York Review of Books and the New Yorker, which serve, boutique-style, a loyal, educated readership. But like the animals that persisted after the great comet struck the earth, most publications will be tiny and eke out an existence in the shadows.

As Walter Cronkite might have said at this point, “And that's the way it is.”