Politics

A Life in the Fray

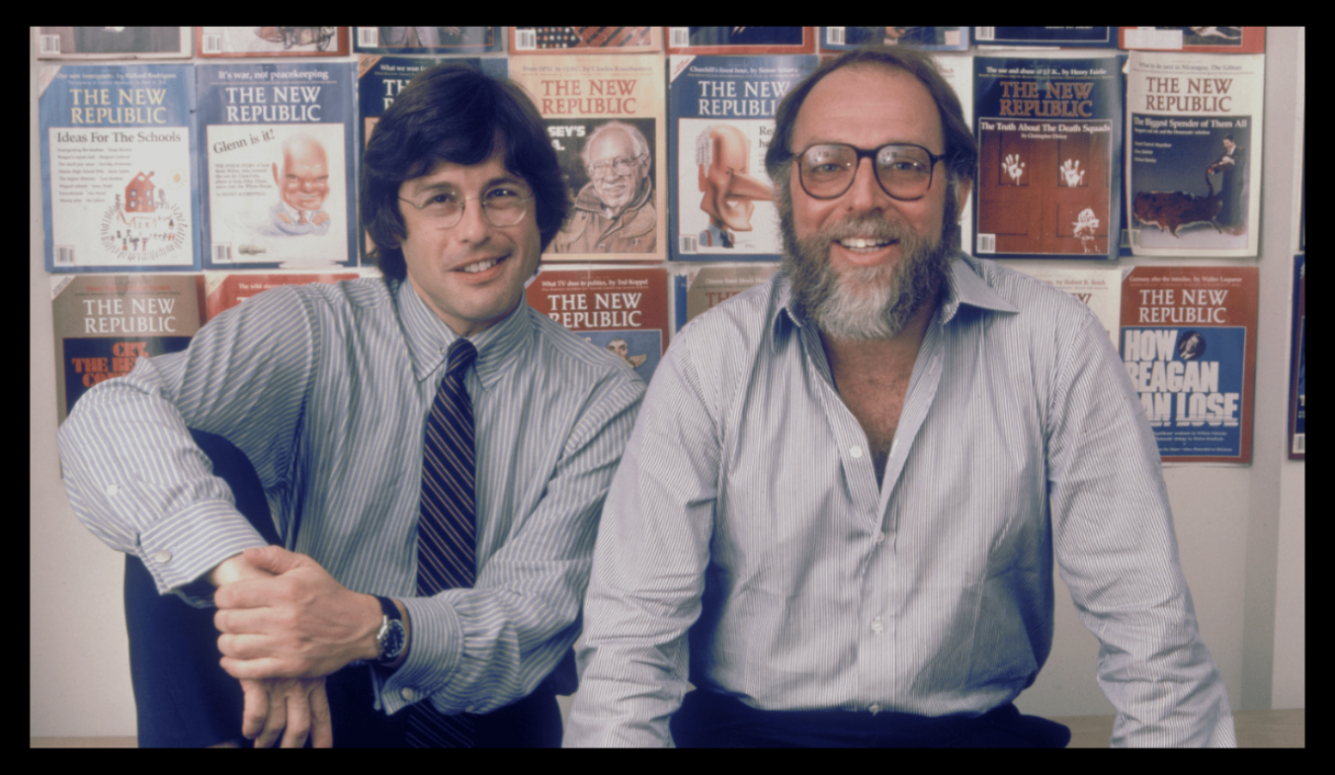

A new memoir by Martin Peretz, the former owner and editor-in-chief of The New Republic, provides a timely reminder of what American journalism has lost.

A review of The Controversialist: Arguments with Everyone Left Right and Center by Martin Peretz, 351 pages, Wicked Son (July 2023)

In 1974, Martin Peretz purchased the New Republic magazine, which had been the preeminent weekly journal of liberal journalism and opinion in the United States since it was founded in 1914. The price was $380,000, roughly 2.3 million in 2023 dollars. Peretz served as the magazine’s publisher and guiding spirit until he sold it in 2011 as it faced financial pressures from “free news” on the Internet and the slow collapse of the liberal center in American politics and intellectual life. In those 37 years, Peretz used his money, political judgment, and intellectual engagement to support the kind of weekly journal that no longer exists in the wealthiest country in the world—that is, one deeply committed to the liberal tradition and willing to defend it against attacks from the Left as well as the Right.

In The Controversialist, Peretz offers us a frank and important account of his intellectual and political journey—his youth in the Yiddish-speaking Jewish neighborhoods of the Bronx, his college years at Brandeis University, five decades of engagement at Harvard University’s Committee on Degrees in Social Studies, nearly four decades at the helm of the New Republic, and finally, the years since he sold the magazine. His agreements and disagreements with a host of prominent intellectuals, journalists, and political figures will interest readers familiar with the last 60 years of American political history. He was, he writes, in the middle of the political fray, most importantly as a publisher.

I do not claim to objectivity regarding The Controversialist. Between 1995 and 2010, I wrote 14 reviews for the “back of the book,” the lively review section edited by Leon Wieseltier, and eight political essays when the magazine went online and was edited by Richard Just. In those years, the magazine (hereafter TNR) was notable in American journalism for being a publication in which one could read both criticisms of the American Right’s attacks on the welfare state and liberal denunciations of communist dictatorships. Under his leadership, TNR generally supported the Democratic Party, but in the essays and reviews by African-American scholars and writers, it introduced nuance into public discussion of race and racism and the causes of poverty. It was a place to follow scholarship on both the Holocaust and the Gulag, and about right-wing dictatorships and the leftist dictators in Central and Latin America.

The Controversialist traces Peretz’s evolution from the intense Jewish ethnic identity of his youth in the Bronx neighborhoods of New York to the political engagements and intellectual liberalism of the 1950s expressed by authors such as Max Lerner, David Riesman, and even Herbert Marcuse. Yet when elements of the New Left turned against Israel in 1967, he was one of the earliest American liberals to notice and oppose their attacks. In the Peretz era, TNR became an unapologetic and emphatic voice supporting Israel and criticizing Arafat’s PLO. He turned the magazine into something Washington had not seen before—a weekly journal written not only for the lawyers and government officials in the capital city but also for a broad English-reading audience of intellectuals and scholars around the world, who were willing and able to engage in debates that rested on knowledge of the American and European liberal traditions. The absence of a comparable publication in the United States today underscores the importance of what Peretz and the editors and writers of the old New Republic accomplished.

Peretz was born in 1938. The news his parents heard on the radio about the Jews in Eastern Europe during the Holocaust “was not just bad in the abstract, for the Jews of Eastern Europe who were being destroyed were not just our people but our family.” He came of age in a community understandably preoccupied with politics and antisemitism. His was a generation of Jews rooted in “neighborhoods and ethnicities,” but one that was also entering into the previously inaccessible upper reaches of the American Protestant establishment, first at Harvard and then in the world of journalism in Washington, DC. The Jewish community of his youth was “a community in mourning.” Most of his parents’ immediate and extended family in Poland were murdered in the Holocaust. His is a story of striving and ascendency, but it is also one of deep disappointment as “the institutions we helped construct” became “divided between specialists and ideologists, experts and deconstructionists, with very little of the breadth—the passion for applying expertise and ideas to real life, and letting real life inform expertise and ideas—that characterized the educated leaders we imagined.”

Peretz laments deepening economic inequality, a society focused on “consumption, not cultivation,” and political divisions stoked by “a media making those divides into cartoons … a multicultural statism that doesn’t ring true to the complexity of life on the ground and an antistate conservatism that feels misplaced, grafted onto an era that no longer exists.” The former publisher of what he calls “the most influential political magazine in Washington” now describes himself as a “marginalized man.” That marginality was a source of creativity and critical reflection, but it came with a price. In this book, Peretz recalls the accomplishments and the costs that come with entering the fray.

Many people shared Peretz’s liberal opinions about political matters, his willingness to risk public controversy, and his ability to write well enough to express views in ways readers might find of interest. What distinguished him from others of his generation was that he combined his political convictions with significant wealth and a willingness to use it in support of his beliefs. He grew up solidly middle-class due to his father’s success with a factory producing pocketbooks and ownership of several rental apartment buildings in New York. Uncharacteristically for a liberal in his senior year at Brandeis, Peretz also “did well” in the stock market. He does not specify how “well” he did, but it seems likely that, by his early 20s, he was affluent but not rich.

It was his marriage to Anne Devereux Labouisse that made the difference. It was an essential precondition for Peretz to attain political influence. Labouisse’s great-great grandfather, Edward Cabot Clark, was the co-founder of the Singer Sewing Machine company. Clark made a fortune from the sale of millions of machines and then added to it with remarkably successful purchases of real estate on the West Side of Manhattan. Peretz does not give specifics about the extent of the family wealth, but he writes that “the Clarks were as rich as the Fricks and maybe even the Rockefellers.” Anne Devereux Labouisse Peretz turned “her money and attention to causes.”

Peretz writes that “you can trust a cause in ways you can’t trust a person, and you can use a cause to direct the money raining down on you toward something more meaningful to your inner self.” That is what Anne Peretz decided to do. Her willingness to use her inherited wealth to advance the political causes she and her husband supported distinguished Peretz from many others of his generation who shared his views. His willingness to take positions on controversial matters emerges in the pages of his memoir. His courage is apparent. But a foundation of wealth enabled him to take risks that others who lacked it would or could not. Many people have money, and many more have strong opinions. Peretz was unique in those years in having both and a willingness to engage publicly in support of liberal causes.

Like so many other young Jewish intellectuals of the early 1960s, Peretz was deeply engaged in the liberal intellectual and political causes of the time before he married Anne Labouisse. His father imparted the idea that there was no contradiction between being Jewish and being an American, or between striving for success in the establishment’s elite institutions while fiercely holding on to the particular identities of Jews in the United States. The Jews of his New York youth “talked politics all the time” because “politics had determined the course of their European lives.”

Peretz fondly and gratefully recalls the intellectual scene of Brandeis University in the late 1950s. In that “liberal and leftist hothouse,” he refined his youthful preoccupation as a student and as editor of its student newspaper, the Justice. He offers interesting descriptions of Brandeis faculty who were important for him, including Max Lerner, a scholar of American history and politics, Frank Manuel, a European historian, and Herbert Marcuse, already prominent in the academy as a leftist political and social theorist. While he found the mixture of Marx and Freud in Marcuse compelling, he was more drawn to Lerner’s liberalism which, like his father’s, included a firm anti-communism.

It was as a graduate student, and then lecturer at Harvard, that Peretz’s very Jewish sensibilities first interacted with the Protestant establishment. There is a great deal about Peretz at Harvard in The Controversialist, from his days as a doctoral student to becoming Head Tutor of the undergraduate honors program, the Committee on Degrees in Social Studies. Peretz gives grateful nods to senior and peer colleagues at Harvard, including the political theorist Michael Walzer, the sociologist David Riesman, the scholar of international affairs Stanley Hoffmann, the historian of Soviet foreign policy Adam Ulam, and comparative historian Barrington Moore, Jr.

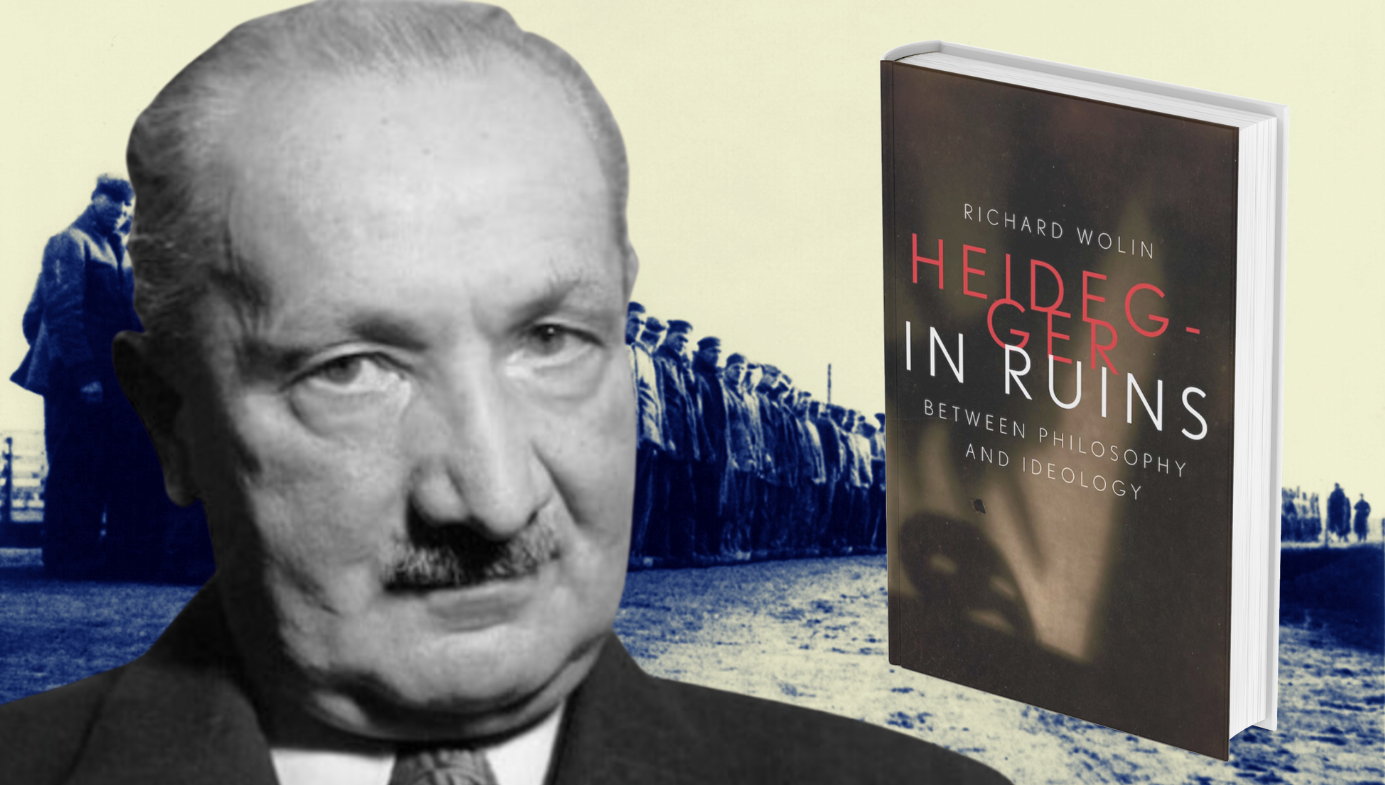

He arrived in Cambridge at a propitious moment. “The America the Protestants had put in place was opening up. We [Jewish students and faculty] knew it, and it seemed like they knew it too. It was my good fortune to walk up to this golden door just as it was opening up.” While “assimilated German Jews” were fostering universalism and distancing themselves from Israel, Peretz struck the balance differently, taking a critical view of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem and expressing his differences with the New York Review of Books, which was established in 1963. An important theme of The Controversialist is Peretz’s efforts as a teacher to, in Daniel Bell’s words, “humanize the technocracy.” But he also writes of his growing unhappiness with the arrogance of specialists who thought the world’s problems could be readily solved by the best and the brightest.

Though Peretz was a lecturer in Social Studies from the late 1960s to the early 2000s, and its Head Tutor in the early 1970s, he says little about the content of that remarkable interdisciplinary undergraduate honors major. That’s a pity, for much—perhaps most—of his time in those decades was not spent contacting prominent government officials or funding political projects. Rather, he was a devoted and effective teacher in a program that combined history and the social sciences and produced several generations of scholars, lawyers, politicians, and government officials.

I taught in the program from 1981 to 1985, and like Peretz, I had the privilege and pleasure of teaching some of the smartest and most engaged students at Harvard and reading with them the core works of the modern liberal tradition. Social Studies was not the “left-liberal hothouse” that Peretz describes at Brandeis. It, and Harvard more generally, was “to the right” of the radical mood fostered by Marcuse’s blend of Marx and Freud that Peretz adopted from his undergraduate education. In that sense, Peretz fitted in well with the predominantly liberal, not leftist, ethos at Harvard in those years.

The core of Social Studies at Harvard was a two-semester sophomore-year sequence of reading established in 1960 by the founders—Stanley Hoffmann, Barrington Moore Jr., Michael Walzer, Alexander Gerschenkron, H. Stuart Hughes, and Robert Paul Wolff—and largely continued when the program was chaired by historians Charles Maier and David Landes, political theorist Seyla Benhabib, and political scientist Grzegorz Ekiert. Peretz taught seminars in the program during those five decades. In that whole period, required reading for all Social Studies majors included large selections from Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Alexis de Tocqueville, Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Sigmund Freud. The guiding spirit of Social Studies was a liberalism skeptical of economic reductionism, utopian promises, and the rationalist optimism of the Marxist Left.

The crucial point is that majors in Social Studies graduated from Harvard having read classic works in defense of the market economy, liberal democracy, the importance of ideological as well as economic factors in politics and, with Tocqueville and Freud, a serious dose of sober and anti-utopian liberalism and skepticism about communism. Today, when I observe the passionate support for Ukraine joined to a sober assessment of American national interests expressed by Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Attorney General Merrick Garland’s defense of the rule of law, or Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer’s pushback against threats to our democracy from the American Right, I hear echoes of Tocqueville, Weber, and Freud that were central to Social Studies seminars when they were all students in the program.

Though Peretz joined and supported the opposition to the American war in Vietnam, the war, its history, and details occupy a surprisingly modest amount of space in this memoir. Born in 1938, he was past draft age when the war escalated in 1965. Peretz portrays the Vietnam war as one of those issues about which one took a position, but it was not a defining episode in his life. Nazism, Communism, the Holocaust, and the Gulag were formative for his political convictions, which had gelled well before Vietnam became the overwhelming issue it was for those of us who were draft age. One of the signal contributions of TNR, both in its articles about communist regimes and movements and in the review section, was to take the history and present of totalitarianism of the Right and Left very seriously in the same years the New Left was proclaiming the virtues of “national liberation struggles” in Vietnam and elsewhere in what was then still called “the Third World.”

What does loom large in Peretz’s account of his 1960s is his ill-fated effort in 1967 to bring together the moderate wings of the Civil Rights movement and those opposed to the American war in Vietnam at a conference he helped to fund called “The National Conference on New Politics.”

Peretz depicts it as a clarifying debacle that brought the issues of black radicalism and the antisemitism of the New Left to the fore. “It was the worst thing I’d ever done,” he writes, “the worst organization I had ever been involved with, and the ultimate example of me being too vulnerable to people and causes on the Left. It was a pivotal moment for me.” Peretz lost control of the conference he had made possible to an alliance between a radical black caucus and white Maoists and communists who denounced Zionism and the United States and called for revolution. He had “an awful feeling that the anti-Semitism of the American Left was no different from that of the Communist parties in Eastern Europe, with the new element of race added to the mix. … Here, decades later, was the American iteration of the Communist mistake, aided and abetted, again, by Jews rejecting their Jewish identity in the name of an ideology that persecuted Jews.”

Peretz writes that he felt “like a fool” for having been thwarted by people “who gave zero thought to the realities of democratic politics,” whose “utopianism” would generate a massive electoral backlash, and who turned the convention “into a dictatorship.” He had “no clout at all. I was supposed to be an activist and a benefactor, but I had compromised my point of view as an activist by allowing myself to be categorized as a moneybags.”

Reading about the National Conference for New Politics. I know he helped fund Ramparts & all, but it still jars me every time I see 1960s Marty Peretz in far-left company. pic.twitter.com/MbiGwjRDjk

— S. Howe / Mastodon: @[email protected] (@louchelarue) October 24, 2020

This clash between liberals and ’60s leftists over Israel was an early chapter in what became a decades-long political battle. As the New Left deepened its antagonism to Israel after 1967, Peretz, like liberal Jewish intellectuals in France and Germany, doubled down on his support for the Jewish state. The criticism of the Left and its turn against Israel would become an enduring theme in the pages of TNR.

Yet the Chicago debacle also showed that Martin Peretz the teacher in Social Studies had evolved into Peretz the political operator. “I was a person who connected the different factions—moneymen, politicians, journalists, academics, and celebrities; democratic socialists, social democrats, and welfare liberals.” In 1972, he gave “enormous” amounts of money to the Presidential campaign of George McGovern, “but had McGovern won, I was convinced it would’ve been a disaster for the country—maybe for the world. I knew that too much of what he believed was what the Left did: that threats to democracy abroad were nonexistent, that the only war was the one here at home.” Living in deep blue Massachusetts, he seized on the luxury of voting for Richard Nixon. “To be perfectly frank, my vote for Nixon was a vote for Israel,” a vote he did not regret when, during the Yom Kippur War of 1973, Nixon decided to implement a massive resupply effort that made it possible for Israel to withstand the Arab attacks.

During that war, Peretz was Head Tutor of Social Studies, a non-tenured academic appointment. He hadn’t published a major book or established a reputation comparable to the tenured Harvard faculty. And yet he called Simcha Dinitz, the Israeli Ambassador to the United States “every morning at 6 or 7, and he’d already have spoken to [US Secretary of State] Henry [Kissinger].” Several days later, he joined Michael Walzer and other faculty in a visit to Kissinger in Washington to urge support for Israel. What was it about the then-34-year-old Peretz that put him on a first-name basis with the Israeli Ambassador and the Secretary of State? Why would the Ambassador give his number to Peretz or even take his call at that hour of the morning? Why did these men in powerful political posts think that Peretz, with his opinions, was someone they should listen to? One wishes he had explained in this memoir. I would guess that the answer lies in the above-mentioned rare combination of wealth, intellect, and political engagement.

Peretz recalls Israel’s survival in October 1973 as follows:

By the end of October, twenty days after the first attack, we had won. Simcha [Dinitz] saved us; Golda [Meir] saved us; Henry saved us; Nixon saved us. If McGovern had been in the White House, he would have been guided by some combination of the moral abstractions of activists and the institutional equivocations of the State Department crowd. And he, they, would have let Israel drown.

The “we” in this statement certainly refers to Jews and to Israel but presumably also to the United States. Peretz was right about Nixon and Kissinger coming to Israel’s defense, especially when the European NATO allies were refusing to permit American planes to land and refuel in their airports for fear of offending Arab oil suppliers. He was perhaps also right about what McGovern would have done had he been president and faced with the Arab invasion of October 1973. These are the events that occupied Peretz’s attention and left a mark on his thinking about American domestic and foreign policy.

With the purchase of the New Republic in 1974, Martin Peretz began the most important chapter of his role in American public affairs. He connected political conviction with his and his wife’s wealth to intervene in American politics and in the intellectual life of Washington, DC. TNR was, he writes, to be “a magazine from the Left but not of it, intellectual but not academic, a publication of ideas that was also where the action was.” In 1979, he hired Leon Wieseltier to be editor of the book review. Under Wieseltier’s stewardship, the review became, along with the New York Review of Books, the preeminent general-interest book review in the United States, and an indispensable part of TNR.

Peretz offers apt descriptions of editors of the magazine’s reporting and journalism, including Michael Kinsley, Rick Hertzberg, and the columnist Charles Krauthammer. Writers like these offered a stimulating mixture of agreements and disagreements, and they shared Peretz’s vision for a magazine that would “poke the polite rationalist establishment in the eye, argue for the old Left belief in political action to better society, champion the humanist concern with the health of the culture, contest policies from first principles, and argue for why Zionism mattered.”

TNR quickly became known not only for its opinions but also for being self-consciously Jewish and intellectual, with a staff educated at Harvard, Columbia, and Oxford.

[Old Washington] thought they had me pegged as a smart-ass pushy Jew. But they didn’t expect the heft, the sheer braininess. They didn’t expect the intellectual commitment. We had in our hearts the worst atrocity in recorded history [the Holocaust], and it affected our thinking, our approach, to the issues of the day. We were something altogether new. There had never been such a widely read magazine of Jewish journalists before. … So, though this was never my conscious plan, the New Republic was a break for identifying Jews and Zionists in Washington.

Washington was, and remains, a capital city filled with lawyers, officials, and policy analysts overwhelmingly focused on the events of the day, the week, or (at most) the month. In this overwhelmingly practical—indeed, at times, anti-intellectual—city, Wieseltier’s “back of the book” was unapologetically intellectual. He invited academics from universities around the country, not only the Ivy League, to write reviews of scholarly works being ignored by the major newspapers. As a result, historians, philosophers, literary critics, novelists, and social scientists saw their books reviewed in a publication that reached a small, general, but serious audience of around 100,000 readers. For this reason, many serious books did not disappear from public view.

The magazine’s critics included an impressive gathering of liberal intellectuals and scholars, white and black, American and foreign—figures such as Mario Vargas Llosa, Henry Louis Gates, Paul Berman, and Stanley Crouch among many others. The interns included Antony Blinken, Amity Shlaes, Dana Milbank, Charles Lane, and Jacob Heilbrunn. Milbank became a columnist at the Washington Post. Lane, also a graduate of Social Studies at Harvard, moved from his position as editor of TNR (1997–99) to the Post where he is now a member of its editorial board. Heilbrunn is now editor of the National Interest in Washington. Writers in TNR were willing to say flat-out that communism was worse than capitalism, that the welfare state was crucial but not beyond criticism, and that the Democratic Party needed a strong centrist component to push back against the currents of post-1960s radicalism that were assuming influence as a tenured professoriate and within the party itself.

For Peretz, the critical issue remained defending Israel in an era of Arab antagonism and PLO terror. He thought he “was one of the few people of influence in Washington, D.C. who understood” the realities of the Middle East, its conflicts of nations, tribes, and peoples that eluded officials in Washington. As he puts it, by the 1980s, “Washington’s main weekly magazine of politics and ideas was going to run articles about Israel that were more than afterthoughts.” It did so in opposition to journalists at the Washington Post who “were unfailingly kind to Arafat—he was lionized by the press as a great liberation leader—and they let themselves imagine him that way for years until his deceptions were too glaring to ignore.” Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and the revelation of the massacre in Sabra and Chatilla by Christian Falangists changed Peretz:

Israel was not a perfect country, and it did not have a perfect army. Its leaders certainly weren’t perfect. But the war had convinced me that people in Washington and the people giving the American public its information didn’t understand what was at stake. They did not grasp the complexities that created Israel’s context and shaped its actions.

Over time, “the flattening of complexities only got worse.”

Peretz does not offer details about how and why he “lost control” of the New Republic in 2008. His marriage was coming apart. He hints at shortcomings in his own managerial style, his outbursts of anger, and admits that he “often picked on smaller, weaker people.” For whatever reason, personal or financial, Peretz eventually decided to sell to Chris Hughes, whose main distinction was having become rich at an early age because he was Mark Zuckerberg’s Harvard roommate and had gotten in on the beginnings of Facebook.

Hughes assumed control in 2012. Two years later, he had already antagonized the entire staff to such an extent that when he fired the magazine’s editor, Franklin Foer, in early December 2014, most of the editorial masthead resigned overnight. The Peretz-era New Republic was dead, replaced by a “vertically integrated digital-media company” that would be a reliably and boringly partisan fan magazine for the Obama administration and sundry progressive causes. If it was read at all in Washington, it was read by people who were relieved not to be subjected to its support for Israel, arguments for humanitarian intervention to prevent genocide, and criticisms of the left wing of the Democratic Party. The magazine’s downward spiral was but one chapter in the story of a weakening liberal center in American politics.

One of the issues that TNR contributors addressed after 9/11, in the last years under Peretz, was the connection between Islamism and totalitarianism, antisemitism, and the justifications offered for terror. TNR then became one of the few places in American intellectual life where liberals such as Paul Berman and I could make distinctions between Islam and Islamism and draw attention to the courage of anti-Islamist Muslim liberals. We were, however, swimming against powerful currents. Leftists and Muslim activist organizations in the United States denounced any such efforts as “Islamophobia” or simply as racism. Meanwhile, an emerging hard Right was fanning hatred of Islam and Muslims. The destruction of the Peretz-era TNR closed an important space where the reactionary essence of Islamist ideology could be examined and denounced. Neither the Bush nor the Obama administration tried to make those distinctions clear, and their failure created a vacuum of criticism that was eventually filled by the demagogy of Trump and Trumpism.

More from the author.

Blogs reduce the time from writing to publication, and some things best left in the desk drawer or on the hard drive make it onto the Internet. In September 2010, in a blog he kept for a while called The Spine, Peretz rightly criticized “the willful blindness of the Western press to human rights abuses in the Muslim world.” Why, he asked, “do not Muslims raise their voices against planned and random killings all over the Islamic world? This world went into hysteria some months ago when the Mossad took out the Hamas head of its own Murder Inc. But frankly, Muslim life is cheap, most notably to Muslims.” But he then went further and wondered if he needed to “honor these people and pretend that they are worthy of the privileges of the First Amendment, which I have in my gut the sense that they will abuse.” This post, which Peretz reprints in full in The Controversialist, raised howls of protest and indignation about the “Islamophobic” editor of TNR from various liberal and leftist journalists—most, perhaps all, of whom had not written anything of substance about the important issue that Peretz had raised, namely the massive terror inflicted by Islamist terrorists on other Muslims. He issued an apology for his “wounding” language, but the damage was done and those looking to denounce him seized the moment.

Peretz describes the abysmal aftermath in which Harvard undergraduates in Social Studies, of all places, denounced him as a racist and an Islamophobe. They urged the program not to honor this former Head Tutor on the occasion of its 50th anniversary and hounded him in demonstrations as he walked through the Harvard campus. Peretz calls it “the most painful episode in my public life.”

It was also one of many episodes in a chapter of the closing of the American mind to the much-needed discussion of Islamist ideology. It reflected the shallow liberalism of the Obama era that spoke of diversity and anti-racism but refrained from speaking honestly about a reactionary ideology that was fueling the terror war against the democracies in Europe and the United States, against Israel, and against liberals in Muslim-majority societies.

In the remaining chapters covering the years since he left TNR, Peretz recalls writing occasionally for the Wall Street Journal, and his criticisms of Obama’s foreign policy toward Israel and Iran. He called Trump a “tribal backlash to Democrats’ arrogant elitism.” Attention to threats to destroy Israel did not disappear from American politics, but the post-Peretz TNR was more interested in defending Obama than addressing them. In foreign affairs, first the American Interest, and then its successor, American Purpose, addressed the issue of Islamist ideology and antisemitism from a liberal centrist standpoint, but the combination of TNR’s journalism and the Wieseltier-edited book-review section was gone. In their absence, gone too was nuanced public discussion about race, crime, and poverty in American cities. Wieseltier founded Liberties, an excellent, very high-brow quarterly journal that keeps the liberal flame alive, and addresses a small, select audience.

Peretz concludes with a gloomy look forward: “We’re in an age of disjuncture, where the wrong people are fighting for the wrong causes and where out-of-touch managers, tribalists, and socialists set the terms of our politics.” Debate, learnedness, and cultivation “among smart talented people” take a back seat to “the migration of radicalism to our national institutions.” That is all well and good, but in this book, Peretz has too little to say about Trump and Trumpism, and about the radicalism and illiberalism that came to dominate the post-2016 Republican Party. He did, however, refuse to join the small choir of American Jewish figures who were so angered by leftist antagonism to Zionism that they found a soft spot for Trump because he was supposedly “good for Israel.”

On the contrary, in February 2023, in the pages of his former adversary, the Washington Post, Peretz joined Paul Berman, Michael Walzer, and Leon Wieseltier in declaring, “We are liberal American Zionists. We stand with Israel’s protesters.” The statement echoed themes that had appeared in numerous TNR editorials during the Peretz era. That statement read in part:

There are people on the left who will call for an end to U.S. military support for Israel. We conclude instead that Israel today needs and deserves support—but of a new and double nature. Israel still needs and deserves the maximum in U.S. military aid—because Israel has real enemies, and its enemies are no less strong than before. Not even a country with a grotesque government deserves to be destroyed.

Yet Israel also needs and deserves maximum political support for the Israeli protesters in the streets. It is the anti-Netanyahu protesters, and not the Israeli government, who represent the hope for the decent and liberal Jewish state that the world needs, that the United States has always favored, and that has served the Jewish people so well in the past. We urge Israel’s truest friends to adopt this kind of double, but not contradictory, support: Yes, to the Israeli defense system and yes to the protesters. And we urge the Biden administration to do the same, and to do it openly and articulately.

In 2023, the United States boasts thousands of multi-millionaires and hundreds of billionaires, many of whom claim liberal convictions. Not one of them—many with far more money than Martin Peretz and Anne Devereux had 50 years ago—has shown the ability or willingness to combine wealth with political judgment to support an intellectually serious liberal periodical that will continue and further develop the legacy of the Peretz-era New Republic. The current version of TNR certainly does not do that. Such a journal would reflect the changing ethnicities of the educated elites, but as the magazine did under Peretz, it would challenge the conventional wisdom of the politically correct Left as well as the antidemocratic temptations of the American New Right. The courage and enduring contribution of Martin Peretz lay in taking issue with his own side—his fellow liberals—and in standing for a tradition, both Jewish and American, of dissidence, marginality, and engagement. The Controversialist is an important work that, like its author, provokes as it enlightens.