film

The Forgotten Ford

Before Han Solo and Indiana Jones, there was another Harrison Ford, a star of silent cinema.

I. The Stars on Hollywood Boulevard

If you’re ever in Los Angeles, you can find Harrison Ford’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame just outside the Dolby Theatre. It’s a prime spot, right where they roll out the red carpet for the Oscars each year.

If you walk a little farther east along Hollywood Boulevard, you’ll find the glitz and glamour starts to fade, as the twinkling theatre lights make way for the fluorescent glare of discount souvenir stores. It’s here, outside the Musso & Frank Grill (supposedly the oldest restaurant in the city) that you’ll find another star dedicated to Harrison Ford. This one is a bit more weathered but otherwise identical to its fellow a quarter mile up the road—right down to the little movie camera icon that indicates an association with the silver screen.

Among the 2,700 stars that make up the Walk of Fame, these are the only ones that form an exact duplicate pair. You might chalk that up to some administrative error on the part of the Walk of Fame committee, perhaps giddy in their overeagerness to honour the actor we all know as Han Solo and Indiana Jones. But the stars actually commemorate two completely unrelated actors. The more prestigiously placed marker at the Dolby Theatre honours the Harrison Ford of the Blade Runner and Jack Ryan movies; the other pays tribute to a now-forgotten star of the silent era.

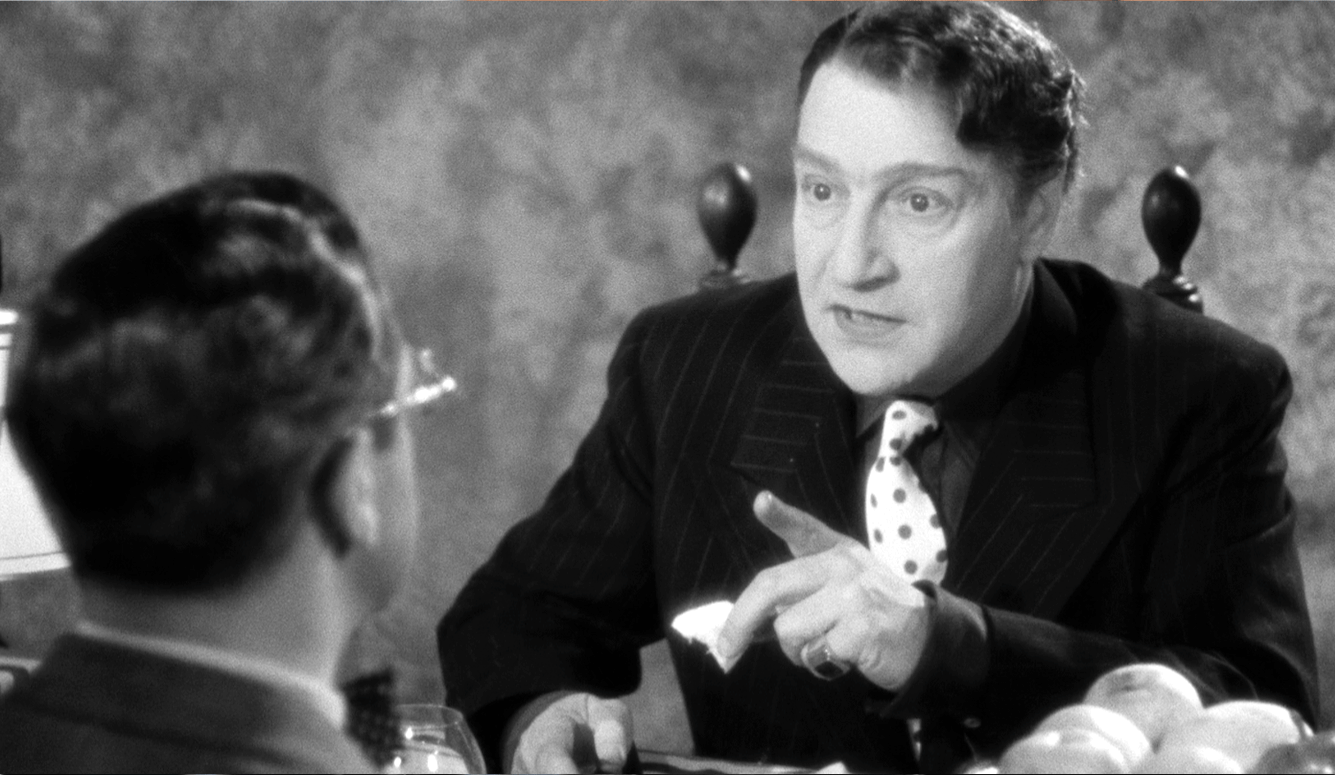

In his time, this Harrison Ford was one of Hollywood’s most popular movie stars. He appeared in over eighty films, alongside the biggest names of the era, including Lon Chaney, Gloria Swanson, and W.C. Fields. He was also directed by some of the most notable auteurs of the day, such as D.W. Griffith (best known for his controversial film The Birth of a Nation) and King Vidor (who straddled the silent and sound eras and directed the “Over the Rainbow” sequence in The Wizard of Oz).

But Ford’s fame came at a time when film was still an impermanent medium. Movie reels took up valuable storage space, so they were often junked after a film had finished its run. Even if it wasn’t destroyed intentionally, the nitrate stock was highly flammable and susceptible to decomposition when not preserved properly. In his book Lost Films, historian Frank Thompson posits that as many as 80–90 percent of films produced in the silent era have vanished forever.

Ford’s filmography comes in at a better ratio than that—just over half the movies he is known to have starred in are lost or incomplete. But those that remain have fallen out of fashion. With the transition from silent to sound and from black-and-white to colour, there is only room for a mere handful of movies from that early era of cinema in our cultural consciousness—and none of them are Ford’s.

All that is to say, that despite his marker on Hollywood Boulevard, Ford’s star has faded considerably. Since his death in 1957, almost nothing has been written about him. And since the release of Star Wars in 1977, any glimmer of remaining recognition has been totally eclipsed by his more famous namesake. Indeed, when he is remembered at all, it is always in conjunction with that other Ford—as the punchline to some trivia question or “did you know?” factoid.

In this way, Ford’s life offers a curious case study on legacy. As his story suggests, none of us can control the way we will be remembered (or forgotten) after we are gone. Societal shifts or strange coincidences can completely change the narratives of our lives and the ways they are interpreted.

Ford never knew of his namesake, or the usurper’s position that younger man would assume. If you asked him to sum up the narrative of his life he might have framed it as a rags-to-riches journey from stage to screen. If Ford wished to be remembered at all, it might have been as a man who loved the theatre, who loved books, and who loved his mother.

All that has been lost. But delving into the archives, we can piece together a more nuanced portrait of this once famous man, and perhaps perform an act of remembrance for one of the stars of the silent screen.

II. Ford’s Life

Harrison Ford was born in Kansas City, Missouri in 1884, and moved to St Louis, on the other side of the state, with his family at a young age. According to a newspaper profile, Ford caught the acting bug in childhood. Back then, the profession was still associated with the theatre. The movies were emerging as a new art form, but were typically just a few minutes long and screened alongside live performances as part of a wider bill of entertainment. The most successful film of that time was 1903’s The Great Train Robbery. Running at around twelve minutes, it was later described by the New York Times as “phenomenally long” for the period.

It was around that time that Ford made his Broadway debut in a play called Ranson’s Folly, alongside Robert Edeson, a notable star of the stage. The teenaged Ford courted Edeson when his touring group passed through St Louis one winter. Ford, who was then working at a railroad office, painted a calendar as a Christmas gift for Edeson. Emboldened by the note of thanks he received, he decided to ambush the star at his stage door, introducing himself as “The Calendar Man” and striking up a long conversation. The following year, after proving himself as an unpaid spear-carrier in a local production of Hamlet, Ford joined Edeson’s troupe, touring the country “as far south as New Orleans and west to the Coast.” Soon, he was fully immersed in the life of the touring actor, travelling not only across America, but around the world. By 1914, he was quoted in one newspaper pretentiously declaring, “Paris is my only hobby. Great guns, how I love that place!”

The following year, Ford made his screen debut in a farce called Excuse Me, which he had previously performed onstage. D.W. Griffith’s racist epic The Birth of a Nation was in cinemas around the same time. With its record-breaking box office receipts, pioneering editing techniques, and three-hour runtime, Griffith’s film showed how far the cinematic art had progressed since the vaudeville circuit shorts of the previous decade. Ford seemed to appreciate this, understanding that the future of the actor’s profession lay onscreen rather than onstage. As one interview with him summed up, “Mr. Ford believes that motion pictures are here to stay and he thinks that as they grow older and as better pictures are produced there will be a serious deficit in the theatre box offices.”

With that, Ford moved to Hollywood, where he took up the role of “the handsome leading man.” Throughout the 1920s, he starred in as many as seven or eight films per year. His bread-and-butter was light comedy roles, often paired alongside leading ladies of the day, such as the sisters Constance and Norma Talmadge. His characters were “usually polite [and] innocuous,” as one newspaper put it. Those attributes, alongside his good looks, soon gained him a reputation as the silver screen’s “nice young husband.” Indeed, much of his fanbase seemed to come from a particular demographic, as suggested by the countless “dainty, scented notes” he received. One leap day, he was sent “no less than ten proposals of marriage through mail from women and girls.”

Along with stardom came riches. In 1924, he earned a salary of US$23,000 from Cosmopolitan Productions—equal to around US$430,000 in present day terms. The following year, he signed with the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, which would later become Paramount. There, his weekly paycheque was US$1,250—equivalent to an annual salary of well over US$1 million today.

But despite this fame and wealth, interviews with him give the impression that Harrison Ford was something of a quiet loner. In one of his earliest newspaper profiles, he declares that his main ambition is to accumulate, “books, and nothing but books.” Other interviews highlight his status as a bibliophile—one calls his love of books a “consuming desire”. Another passion of his was music, but “he insisted upon his entire inability to go to concerts except alone.”

Indeed, Ford’s primary companion seems to have been his mother. “I love art and opera better than anything,” he once said, “except my mother.” Although he married in 1909, various magazine gossip pages suggest he later divorced, and his mother seems to have been the only constant presence in his life. They even lived together when he moved to California.

Ford’s strange hobbies and reclusive behaviour were often commented on in the press. A 1926 profile in the film magazine Photoplay describes him as “Not only the hermit of Hollywood, but of the entire motion-picture world.” Another article notes that, “He apparently does not wish stardom, or else he is very modest about it.” It’s an observation that seems at odds with the handsome actor who was once described as cinema’s “most popular leading man” and topped a popularity contest of Hollywood stars in 1927.

Indeed, trying to understand the life of Harrison Ford through old newspapers and archival materials, one is continually struck by the contradictions. He sought out a career in the collaborative field of theatre but seems to have desired nothing more than solitude. He transitioned to the silver screen, believing it to be the next big thing, yet had no desire for fame. Most strangely of all, one newspaper profile notes that Ford was “camera-shy.” That final paradox seems to encapsulate his character—a man who was uncomfortable in front of cameras, but somehow became a movie star.

III. Ford’s Legacy

Today, when critics compile lists of the greatest silent movies, Harrison Ford’s filmography is never represented. The canon of silent cinema has been well established by this point, invariably lauding titles like Battleship Potemkin (1925), The General (1926), and The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). Ford’s light comedies don’t match up to the serious intentions and technical innovations of films like those. But some of his surviving movies are historically noteworthy, nonetheless.

One of these is 1922’s Shadows, in which Ford stars alongside Lon Chaney, who was known as “The Man of a Thousand Faces” thanks to his pioneering use of makeup. Today, Chaney’s yellowface portrayal of a Chinese laundryman might be considered offensive by some. But at the time, it would have been thought more sympathetic than insensitive. While it was not the first Hollywood film to prominently feature a Chinese character, Shadows remains an important early example of East Asian (mis)representation in American cinema. And the film had its champions. Robert E. Sherwood, a critic who would go on to receive four Pulitzer Prizes and an Academy Award, deemed it “an unusually fine picture,” naming it as one of the best of the year.

That same year, Ford also starred in Smilin’ Through, a film cited in his obituary in Variety as the one for which he was “best known.” It certainly seems to have been among his most popular films, spawning two remakes, including a 1941 Technicolor musical version by Frank Borzage, who won the first ever Oscar for Best Director. The film took US$1 million, which made it one of the highest-grossing movies of the time. It was also deemed the seventh best film of the year based on an aggregated list sourced from critics, and was cited by Mary Pickford (the first woman to sign a million-dollar movie contract) as one of her favourite films.

Another of Ford’s more popular films was made in 1925. This time, he collaborated with King Vidor, a Hollywood legend, who directed his first project in 1913 and his last in 1980. The movie is particularly notable for its place in Vidor’s filmography, having been made in the same year as his World War I epic The Big Parade, which the American Film Institute claims is “frequently described as the most successful silent film of all time.” Ford’s film, titled Proud Flesh, was not quite in the same league. But his performance as “a Latin lover” was named as one of the best of the month by Photoplay, a film magazine whose accolades were a major precursor to the Academy Awards.

However, Ford’s most significant film is one we will never see. Released in 1925, That Royle Girl, saw Ford team up with D.W. Griffith, the most innovative director of the silent era, and W.C. Fields, a comic actor whose influence is still felt today. It is considered one of the most important lost films of the period and was named by the American Film Institute on its “Ten Most Wanted” list in 1980. Despite this, no copy of the film has ever been found.

The film was Griffith’s first with Paramount, having previously worked under his own production company. This new contract forced a script on him that was different from his usual historical melodramas, with a plot revolving around a love triangle and murder conviction in the Chicago jazz belt. Film historian Frank Thompson argues that Griffith’s “heart wasn’t in the film.” But even if the script was unworthy, Thompson notes that Griffith “could triumph over the most preposterous balderdash”—which might explain why the film is deemed so desirable.

Based on the contemporary reaction, That Royle Girl seems to have been a modest success. Though it was not a major hit, it brought a respectable return at the box office. And the critical responses ranged widely. The New Yorker gave it a negative review, dubbing Griffith “the grand master of moralistic-melodramatic balderdash.” At the other end of the spectrum, The Herald Statesman was hyperbolic in its praise, declaring that “the picture itself is the last word in the art” and claiming that “never again will a cast as remarkable as the one in this be assembled for a screen attraction.”

In any case, we will have to content ourselves with never knowing exactly what this mysterious film is like. And though it is a shame that Harrison Ford’s most historically important screen performance should be lost forever, it is also oddly appropriate. After all, this is a man whose own fame and legacy would soon be eclipsed entirely—as the era of silent cinema made way for sound, and a new generation emerged to supersede those original Hollywood stars.

IV. Ford’s Death

Harrison Ford gave his final onscreen performance in 1932 in a film called Love in High Gear. It was the only “talkie” he ever appeared in. The transition from silent film to sound seems to have been a difficult one for many Hollywood stars. They had become used to performing in a certain exaggerated way, which just didn’t work once dialogue was introduced. And fans had gone years without knowing what their favourite stars sounded like. To finally hear the voice of the screen’s “nice young husband” may have shattered the illusion for Ford’s female fans. Not that it was a bad voice. But nothing could compete with those legion fantasies, projected for years onto his voiceless, handsome face.

In truth, Ford’s film career had already been winding down by that point anyway—even though he was still only in his forties. Prior to Love in High Gear, he had gone two years without making a movie. The last truly productive year of his film career was 1928, when he made seven movies. But that was also the year Lights of New York was released (the first feature length film that was all talking) signalling an end to the era of silent cinema.

With the conclusion of Ford’s film career, his presence in the media dropped off significantly, so his biography becomes harder to trace through archival materials. We know that he returned to the theatre, directing at a local company in Glendale, California. And during World War II, he toured for the USO, providing live entertainment for the United States Armed Forces.

But in 1951, a tragedy returned Ford to the headlines, when he was struck by a car near his home. The incident was reported across the country. But Ford’s celebrity had dwindled to such an extent that each article needed to explain who he was—that name no longer carrying any weight of recognition. Even his local paper, The Los Angeles Times, saw fit to clarify that he had “appeared years ago in silent films.”

The accident was so severe that Ford never recovered. He spent his final years at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital and died there in 1957. By that point, his fame had faded so much that his death was ignored by the press. Where it was covered, the tributes were brief—an obituary in Variety ran to less than 100 words. Even so, when the Hollywood Walk of Fame was opened in 1960, his name somehow made it onto the list and his marker was among the inaugural cohort installed in that first year.

By that point, however, another Harrison Ford was making a start on his acting career. Like the original Ford before him, this young man began onstage, before eventually moving to Hollywood in 1964. This new Ford became aware of his predecessor only when he was informed by the Screen Actors’ Guild that his name was already taken on their registers—the Guild was seemingly oblivious to fact that the original Ford had been dead for almost a decade. It’s for this reason that the credit “Harrison J. Ford” appears in the actor’s first significant role, in 1967’s A Time for Killing. When Ford later found out about his namesake’s death, he immediately dropped the ‘J’ and began his movie career in earnest.

It was a slow burn for the new Ford initially. He was selective with his roles and worked as a carpenter until the right projects came along. He had his breakthrough with 1973’s American Graffiti, an ensemble movie in which he teamed up with director George Lucas for the first time. The following year, he worked with Francis Ford Coppola on The Conversation, before finally landing his breakout role as Han Solo in 1977’s Star Wars.

By then, the original Ford had already become something of a punchline. Mark Hamill remembers his Star Wars co-star joking that “he already had a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame” during filming. And when it came time for the new Ford to get his own star, the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce were seemingly in on the joke too. “I almost put the current Harrison Ford’s star next to the other Harrison Ford’s star in order to drive people nuts,” said Ana Martinez, Producer of the Walk of Fame ceremonies.

But it seems unlikely that anyone ever really considered placing the new Harrison Ford’s star up on that section of Hollywood Boulevard, under the single-storey glow of the knock-off souvenir stores. His star was always destined for somewhere suggestive of a more lasting fame. But of course, if his predecessor’s story is anything to go by, that very concept of lasting fame can only be doomed to failure.

V. The Stars on Hollywood Boulevard

When the original Harrison Ford died, he was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. He’d come a long way from his humble beginnings in St Louis to end up here—in the cemetery of the stars. At the time of his internment, other famous names buried there included Humphrey Bogart, as well as his old co-stars Lon Chaney and W.C. Fields. And since then, countless Hollywood icons have joined him—from Clark Gable and Sammy Davis Jr. to Elizabeth Taylor.

Part of the appeal of Forest Lawn is its general atmosphere of prestige and exclusivity—a basic funeral package today starts at US$14,000. And for its most valued clients, it even offers the prospect of everlasting fame in its Great Mausoleum, where a select few are designated as “immortals.” But while some names in Forest Lawn still resonate, a stroll through the Great Mausoleum disproves any promise of eternal fame—few of those “immortals” spark any recognition whatsoever today. And so it is with the Hollywood Walk of Fame just six miles away. Those names on Hollywood Boulevard may be carved in stone. But they are etched into the cultural consciousness much less deeply. Indeed, who today remembers Art Acord, Mary Boland, Hoot Gibson, or countless other movie stars who received their memorials just a few decades ago?

But for all its false promises of lasting recognition, there is something appropriate about the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In the celestial sense, stars inhabit the skies, looking down on us mortals from an incomprehensible distance. But in Hollywood, the stars are brought down to earth, embedded in concrete, and trampled underfoot by indifferent tourists. It’s a fitting image for a monument that is dedicated not to achievement as such, but specifically to fame. Because fame is always fated to pass. So, as the Hollywood sightseers march along in search of today’s celebrity, they inevitably tread over countless others whose names no longer mean anything at all.

Perhaps that’s why the story of Harrison Ford feels particularly poignant. Unlike the other forgotten stars of the silent era, his marker isn’t simply trampled and ignored. Indeed, it attracts countless tourists every year. But all of them visit in the mistaken belief that his star belongs to another man. Thus, Ford has not simply been overtaken by a new generation. His entire identity and legacy have been subsumed by a man he never knew, who literally took over his name.

That literalness in Ford’s story brings home something we all know, but often fail to confront—that every one of us is destined to be replaced and forgotten, whether we are famous or not. It’s hard to imagine from the tiny vantage point of our brief lifespans. But it’s the fate of us all—even someone as famous as today’s Harrison Ford. He may not be replaced by another literal namesake. But subsequent generations will nonetheless come along, heralding new stars and new art forms that will do for Star Wars and Indiana Jones what the talkies did for silent film.

More likely still, his star (and every star on Hollywood Boulevard) will gradually be worn down by the feet of tourists and the winds of time. Eventually, it will be forgotten entirely. Then perhaps, in a hundred or a thousand years, when California is nothing but a desert, some traveller from an antique land may stumble upon a stone tablet amidst the ruins of the Dolby Theatre, brush the dust from its barely legible etchings, and wonder: “Who was Harrison Ford?”