A review of China’s World View by David Daokui Li, 288 pages, W.W. Norton and Co. (January 2024)

In the intensifying competition and looming confrontation with China, many Americans in and out of government have been remarkably slow to grasp the nature of their adversary. Never one to let the search for truth get in the way of an opportunity for a bon mot, Thomas Friedman recently told Ezra Klein that, contrary to the narrative spun by American hawks, the Chinese government does not seek to spread Marxism around the world. Rather, Friedman quipped, its overriding objective is to spread Muskism—manufacturing and technology. In other words, Beijing is not so much aspiring to empire; it means to beat us at our own game.

This view of the competition unfolding across the globe between the established liberal hegemon and the ascendant totalitarian pretender to that throne is not well-founded. As President Trump continues to fire tariff salvos at Beijing, and as the Chinese authorities fire back, it has become abundantly clear that both parties understand the competition in which they are engaged to be zero-sum. A torrent of recent books about the possibility of armed conflict between the United States and the People’s Republic has shed important light on how these fixed antagonists may be, to borrow one prominent title, “destined for war.”

However, in this cornucopia of contemporary accounts purporting to elucidate the sources of Chinese conduct, precious few venture beyond popular bromides about Chairman Xi Jinping’s fierce nationalism and his long-term project to avenge the “century of humiliation” that lasted from the First Opium War to the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. It is rare to see firsthand sources and influential figures in the Chinese Communist Party cited at any length to elaborate the CCP’s worldview. And vanishingly few of these accounts are the fruit of Chinese nationals.

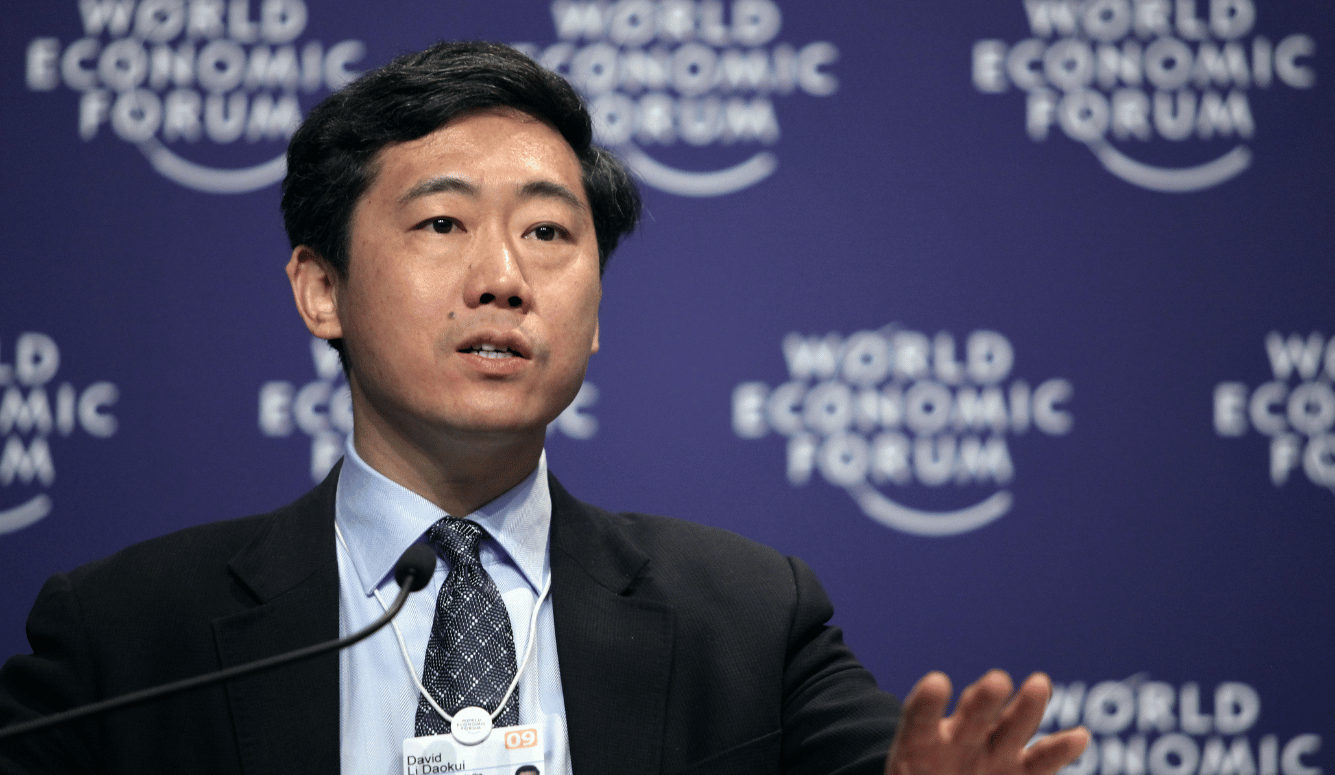

This is one reason why China’s World View stands out in the sprawling universe of the US–China book club. Its author, David Daokui Li, is a professor of economics and director of the Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking in Beijing. He is therefore well-positioned to understand the finer points of Chinese history and how the Chinese system has developed over time. What’s more, he has an intuitive feel for the social texture of China’s ruling elite, though the philosophy of power that animates it is another matter.

China’s World View kicks off by recalling a debate in which its author participated. In 2011, at Toronto’s Roy Thompson Concert Hall, Li took the stage alongside the historian Niall Ferguson to square off against Henry Kissinger and the CNN foreign affairs host Fareed Zakaria. The motion before the house was “The 21st Century Will Belong to China,” which Ferguson and Li were proposing. A poll of the audience at the end of the debate found that they had persuaded this urbane Canadian audience that the American century would not reach its centenary. In the years since, it has become conventional wisdom that Eastern discipline and Western decadence have made the Chinese century inevitable.

Despite his good showing in Toronto, however, a moment during the debate suggested to Li that the world lacked a proper understanding of China and its public philosophy. As President Richard Nixon’s secretary of state, Kissinger had “opened up” the Sino-American relationship with Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai in 1974. He now rhetorically asked his opponents in Toronto: “Look at the world map—how many friends can China truly claim? Especially look at the neighbors of China … how many of them are truly comfortable and trustful with the rise of China?”

Li was dumbfounded. Coming from China and knowing how assiduously the People’s Republic has sought to “show its goodwill and earn respect from the rest of the world,” Li realised that his country’s global reputation desperately needed better PR. By drawing attention to an obvious fact about the pervasive fear and suspicion engendered by the CCP, especially in the Indo-Pacific, the elder American statesman had convinced Li that he needed to write China’s World View.

The purpose of the book, its author explains, is to provide an insider’s view of “how China works.” After defining the PRC’s worldview as the “widely agreed upon general principles shared among the country’s top decision-makers and the educated general public,” Li stresses China’s remarkable economic emergence and distinctive system of “state capitalism.” From the beginning of Deng’s reforms in 1978 through Xi’s ascension in 2013, China’s GDP growth averaged an astonishing 9.9 percent per year. Even though that golden age has ended, it birthed a diversified manufacturing-based economy that is quickly closing in on its Western peers in technological capabilities and competitiveness. Notwithstanding the recent slowdown in China, it is making great strides toward Xi’s objective of becoming “a great modern socialist country,” as he declared in his political report to the Chinese Communist Party’s Congress in October 2017.

Cracking open China’s World View, it quickly becomes apparent that it will not dwell on the dark underbelly of the world’s largest and strongest one-party state. Xi Jinping has abandoned the market-oriented approach that helped China escape its grinding poverty in favour of state control. But Li offers no dissent whatever on the “China model.” He does not criticise the predatory nature of the Chinese Leviathan, which has hollowed out any notion of private property while doling out privileges for inefficient state-owned enterprises. The cursory attention he pays to rapid demographic ageing and environmental degradation does not seriously address how these phenomena will rend China’s social fabric and undermine sustainable economic development.

But it is the terrible risks of China’s over-centralised regime in the realm of global politics and strategy that are most occluded in China’s World View. The previous generation of Chinese leaders believed in pursuing a “peaceful rise,” in which the country prioritised commercial relations over less tangible interests. Li gives every indication that he continues to believe this quietist strategy animates the CCP. But it is now obvious that Xi’s clique is unprepared to tolerate an American-led international order indefinitely. It has taken military action against India over disputed territory, demanded that Australia bend the knee on a range of issues from Huawei to Hong Kong, and laid claim to long-recognised international waters. Most ominously, Xi has declared that Taiwan will be “reunified” with the Chinese mainland before the end of his rule.

By eliding the authoritarian nature of the Chinese state and the abundant evidence of its power projection, Li fails to explain why so much of the world looks upon the “China Dream” with a jaundiced eye. He appears to believe that this ferocious anxiety can be attributed to a serious misunderstanding. So, China’s World View aims to dispel what he regards as global ignorance and the tremendous fear China generates. In the process, he exhibits extravagant faith in the ability of dry language and economic graphs to elucidate China’s good intentions and resolve disputes between nations.

Li places particular emphasis on two factors that, in his telling, meaningfully shape China’s approach to the world. The first is a keen focus on solving domestic issues before expending much energy on global affairs. The second is a fierce hunger for international recognition and respect even at the expense of its economic interests. In combination, he argues, these animating principles imply that China “is not in a position to expand its ideology” abroad, let alone to “undermine the current world order.” Therefore, he maintains, “the rise of China is not a threat to the rest of the world.”

This is a grave misreading of Chinese intentions as well as a severe understatement of Chinese strength. Although the fundamental objective of Beijing’s foreign policy is certainly to “gain proper respect rather than tangible interests,” this is hardly a recipe for peace and comity. The beginning of wisdom in grappling with the CCP is taking stock of its profound dissatisfaction with the American order created after World War Two. China is embarked on a globe-spanning contest with American power that would be familiar to Plato and Hegel—a craving for recognition as a master of History. It already has this ambition in spades; what it lacks, so far, is the currency of legitimacy that can only be conferred by others. Here, the US stands in China’s way as the greatest power in Asia and the leader of an “anti-hegemonic” coalition constructed to thwart China’s designs. China seeks to neutralise this coalition by attacking its most vulnerable members and demonstrating that US defence commitments cannot protect them. By laying waste to American prestige (almost certainly by targeting Taiwan), it will invariably burnish its own.

But does China have the economic and military resources necessary to achieve this lofty pursuit of national and imperial greatness? Over the past generation, China’s economy has substantially closed the gap with America’s. It now dwarfs the economies of America’s previous great-power rivals, including Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. As the US governing class and military brass increasingly acknowledge, China is in the midst of a historic military buildup. It can no longer be denied that the CCP has become a near-peer rival. The People’s Liberation Army has rapidly expanded its nuclear forces, developed critical military technologies that match or even exceed US innovation, and constructed the world’s largest navy outfitted with an enormous arsenal of anti-ship ballistic missiles that would wreak havoc on US aircraft carriers in a war. These factors make its drive for hegemony credible and likely to succeed unless it is deterred and thwarted by sufficient counterforce.

Given its sprawling ambition and formidable strength, in other words, China’s active pursuit of greatness undercuts Li’s magical optimism. By all appearances, the obtuse points in China’s World View spring from its author’s academic pedigree. In his Ivory Tower, Li has nurtured the belief that the West has nothing to fear from China’s emergence on the world stage. To anyone with a sense of history, however, this judgment is naïve beyond measure. Power changes nations in fundamental ways, and China shows no sign of being an exception to this historical rule.

In this sympathetic account of the new China, the Communist Party is portrayed as a misunderstood titan. But it is Li who fails to comprehend his subject. In most of the post-Mao era, Chinese foreign policy was indeed driven by the priority of doing nothing to jeopardise economic development. But this pragmatic sensibility has vanished since Xi’s rise to absolute power. A more assertive and ideological Chinese foreign policy has since announced itself. The free world must adjust to that unwelcome fact, even if obscurantists and propagandists for the regime in Beijing prefer to deny it.

It is past time for Americans and their allies abroad to give more serious consideration to the Chinese worldview. It deserves attention separate from whether it is legitimate or attractive. Indeed, given China’s tremendous newfound power, its worldview demands deep understanding precisely because it isn’t either of those things. Readers may begin their study of that interesting subject with China’s World View, but they should not end there.