Nations of Canada

Wendake or Bust

In the 26th instalment of ‘Nations of Canada,’ Greg Koabel describes Jesuit efforts to study and proselytise the Wendat people amid the Indigenous political tumult of the 1630s.

What follows is the twenty-sixth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialised Quillette project adapted from Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name.

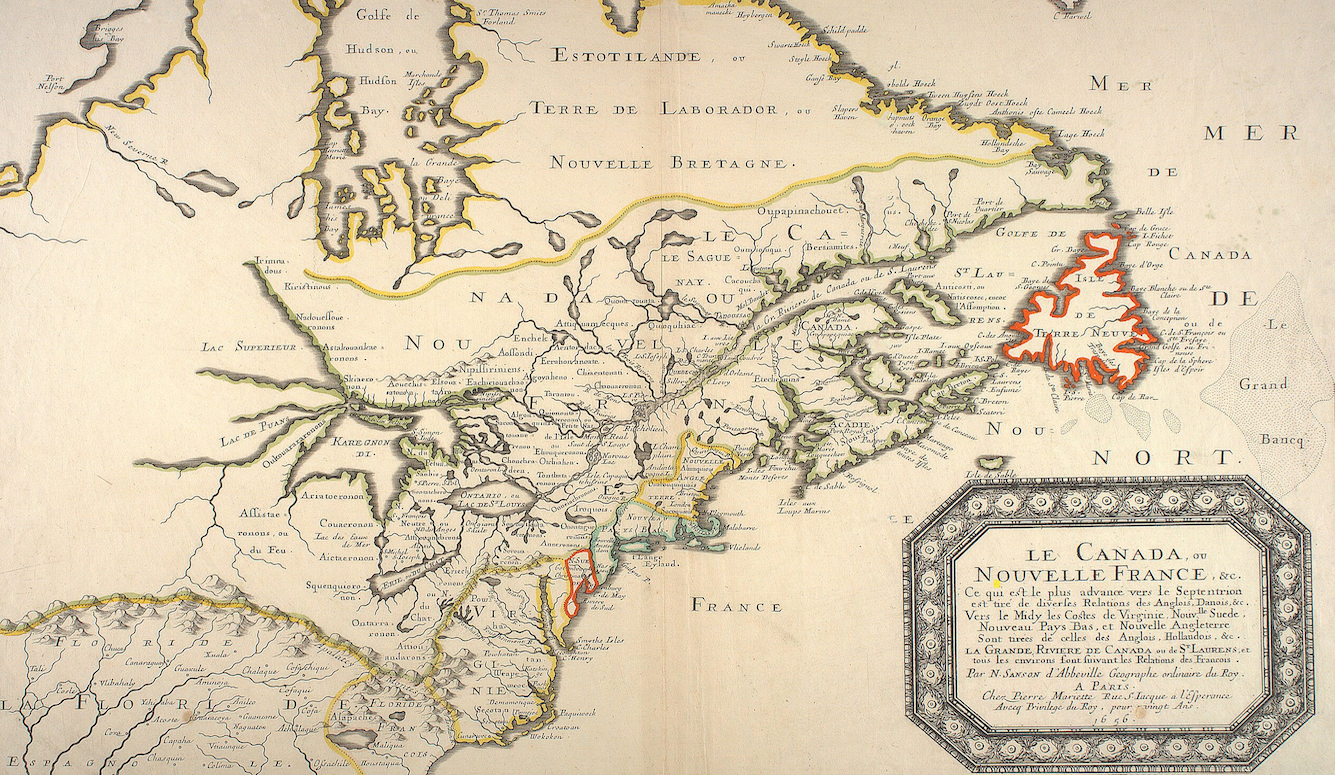

In our last instalment, we looked at how France began rebuilding its colonies in Quebec and Acadia, territories that had been temporarily occupied by English and Scottish interlopers during the Anglo-French War of 1627–29. This time, we’ll be looking at this period from the perspective of France’s Indigenous allies in the region. Would Samuel de Champlain’s old Laurentian Coalition be renewed? Or had circumstances made the old arrangements obsolete?

A key aspect of Franco-Indigenous relations during this period is one that I deliberately left out last time around: religion. Far from merely preaching to the settlers huddled around France’s fledgling Canadian settlements, the Jesuits had taken on a leading role in managing diplomatic links with First Nations—in large part because they were the Frenchmen who’d made the closest study of Indigenous languages and culture.

Readers will recall that the Jesuits hadn’t been the first French missionaries dispatched to Quebec. They’d supplanted another group—the more modestly resourced Récollets, who’d been unable to make much headway in preaching Christianity to Indigenous communities. Unlike the Récollets, the Jesuits had powerful allies in the halls of French power, as well as a well-developed missionary network in many other parts of the world.

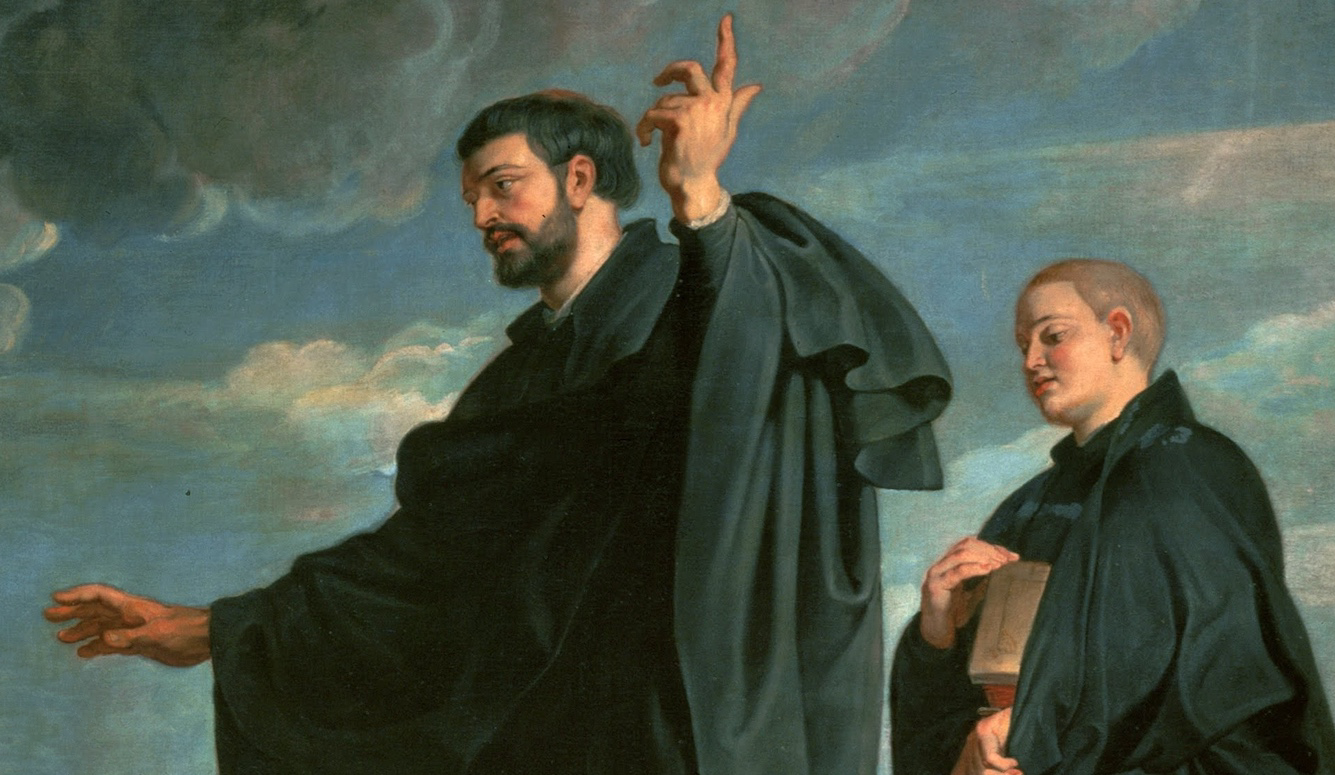

The Society of Jesus (as the Jesuits are more formally known) was founded in 1540 as an early expression of the Catholic resurgence that followed the rise of Protestantism in Europe. But in addition to seeing themselves as “soldiers of God” fighting for Europe’s Counter-Reformation, the Jesuits were also rigorous educators and archivists, known for their attention to professional detail. King Louis XIII and his chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, thus viewed the Jesuits as attractive colonial partners, since they could combine their missionary work with roles as diplomats, linguists, and clerks.

In Asia, the Jesuits had already discovered that directly challenging existing local belief systems was not always the most effective way to spread Christianity. Instead, they concluded, missionaries should first make a thorough study of traditional practices, so as to find existing rituals and values that seemed to have some Christian equivalent. The idea was that once such bridges were built, the erroneous (as Jesuits saw them) elements of pagan belief systems could be stripped away, thereby exposing the kernel of Christian truth lodged within.

It was typical of Jesuit practice that this was both an empirically tested, pragmatic approach; and one that was backed by rigorous theological argument. The Jesuits believed that all humans have an innate understanding of the Christian God buried deep within them—a vestige of the original knowledge that had been lost when Adam and Eve were banished from Eden.

This approach put the Jesuits very much at odds with the Récollets, whom they’d eventually supplant. The Récollets had concluded that Indigenous culture was an insurmountable obstacle to Christian conversion. According to this view, potential converts—such as Quebec’s Innu neighbours—had to first be transformed into French-speaking farmers living in European-style villages. Only then would the idiom of Christianity become comprehensible to them. (Anyone interested in the doctrinal dispute between the two groups has a rich historical trove to draw on, as both Récollet and Jesuit missionaries wrote detailed accounts of their activities in Canada, often using such documents as a means to prosecute arguments about the best way to win Indigenous converts.)

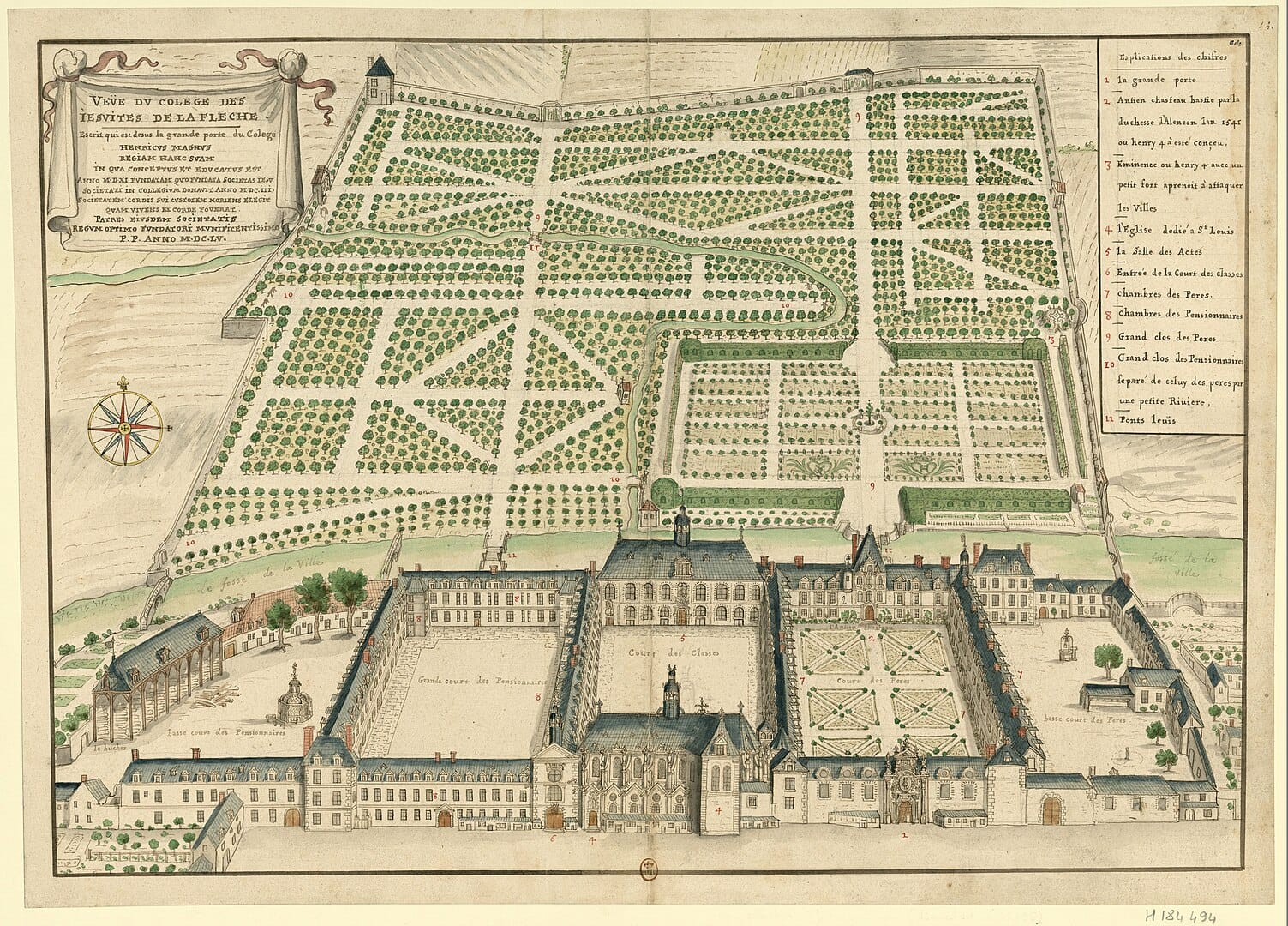

The Jesuits were a tight-knit group, as most of them were inducted into the Jesuit order through education at the same school—the Collège Henri IV de La Flèche, in the Loire Valley. One of the school’s teachers was Énemond Massé, who’d personally staffed the ill-fated Jesuit mission to Acadia in 1613 (whose quick rise and fall we covered in our seventeenth instalment). He encouraged his young students to take up the mantle of a Canadian mission so that they might succeed where he had failed.

But the most influential teacher at La Flèche was Louis Lallemant, who oversaw the transition of students into full-fledged members of the Society. His protégés included a who’s-who of the most important Jesuits who will soon be dominating our story. These men didn’t just share a Jesuit outlook in general, but also the distinct sub-type taught by Lallemant—an ascetic and mystic who believed that a Jesuit’s outward-directed missionary work was inseparable from his internally directed project of spiritual development.

In other words, as Lallemant saw it, the physical and mental travails that accompanied missionary work were important—and even desirable—aspects of the experience. Christ had not achieved redemption through his teaching, but on the cross, through the shedding of his blood, and, ultimately, in death. No missionary could be successful, Lallement said, without “failures, slanders, injuries, and sufferings.”

Thus were the Jesuits who went to Canada seeking spiritual self-purification through pain as much as the conversion of heathens. Or as a member of the next generation of Jesuit missionaries, Claude-Jean Allouez, put it, “Old France is good for conceiving fervent [i.e. earthly] desires, New France for executing [i.e. purging] them.”

As the Récollets had found, however, Canada did not exactly meet those expectations (at least, not yet). Indigenous communities tended to listen politely to Christian preachers rather than respond violently. The Jesuits did find some consolation (if that is the right word) in the physical hardships that accompanied life in the Canadian wilderness. But martyrdom remained, for now, a remote prospect.

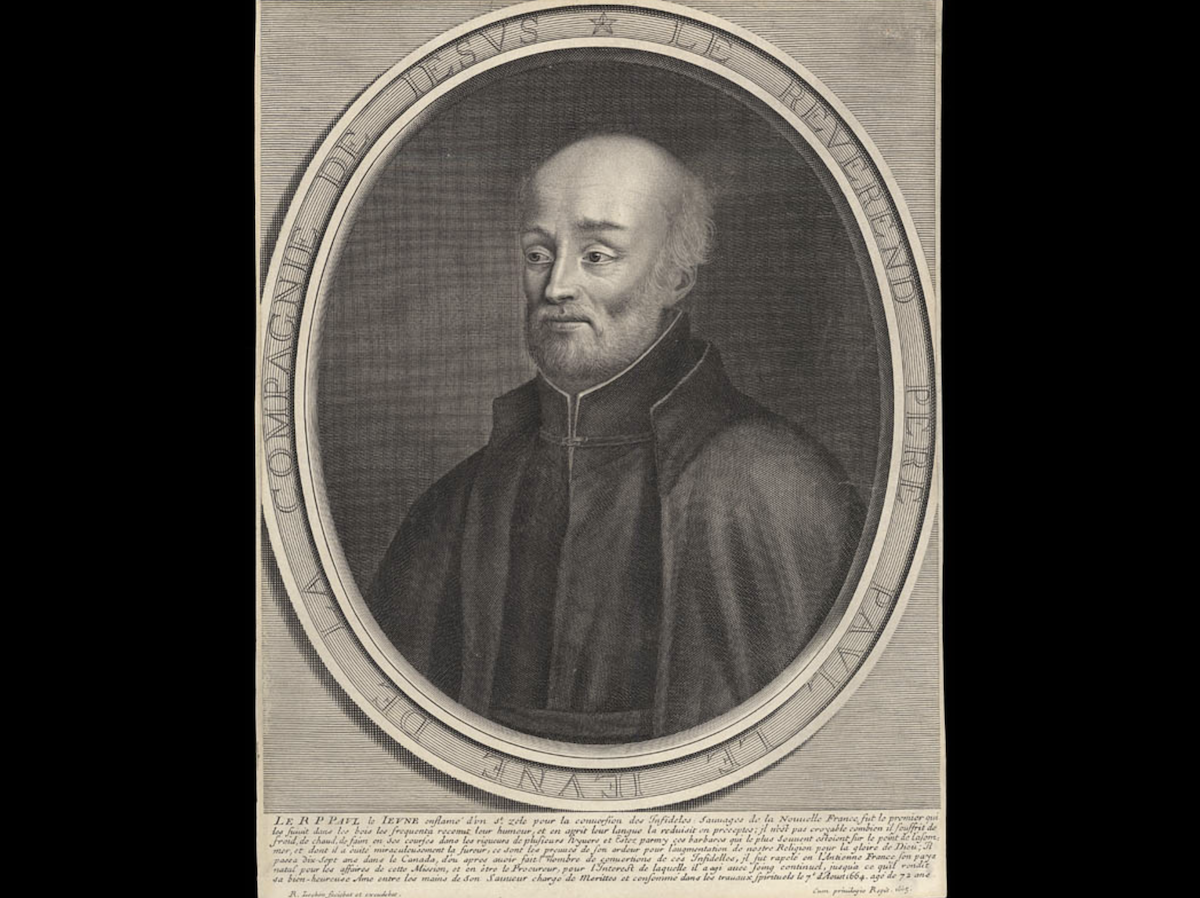

Leading the Jesuit mission to Canada (with the rank of “Superior”) was Paul Le Jeune, a La Flèche graduate in his early forties. From the Jesuit headquarters in Quebec (modern Quebec City), he co-ordinated with French colonial officials and oversaw the writing of the Relations des jésuites de la Nouvelle-France, annualised chronicles of the Jesuit mission to New France.

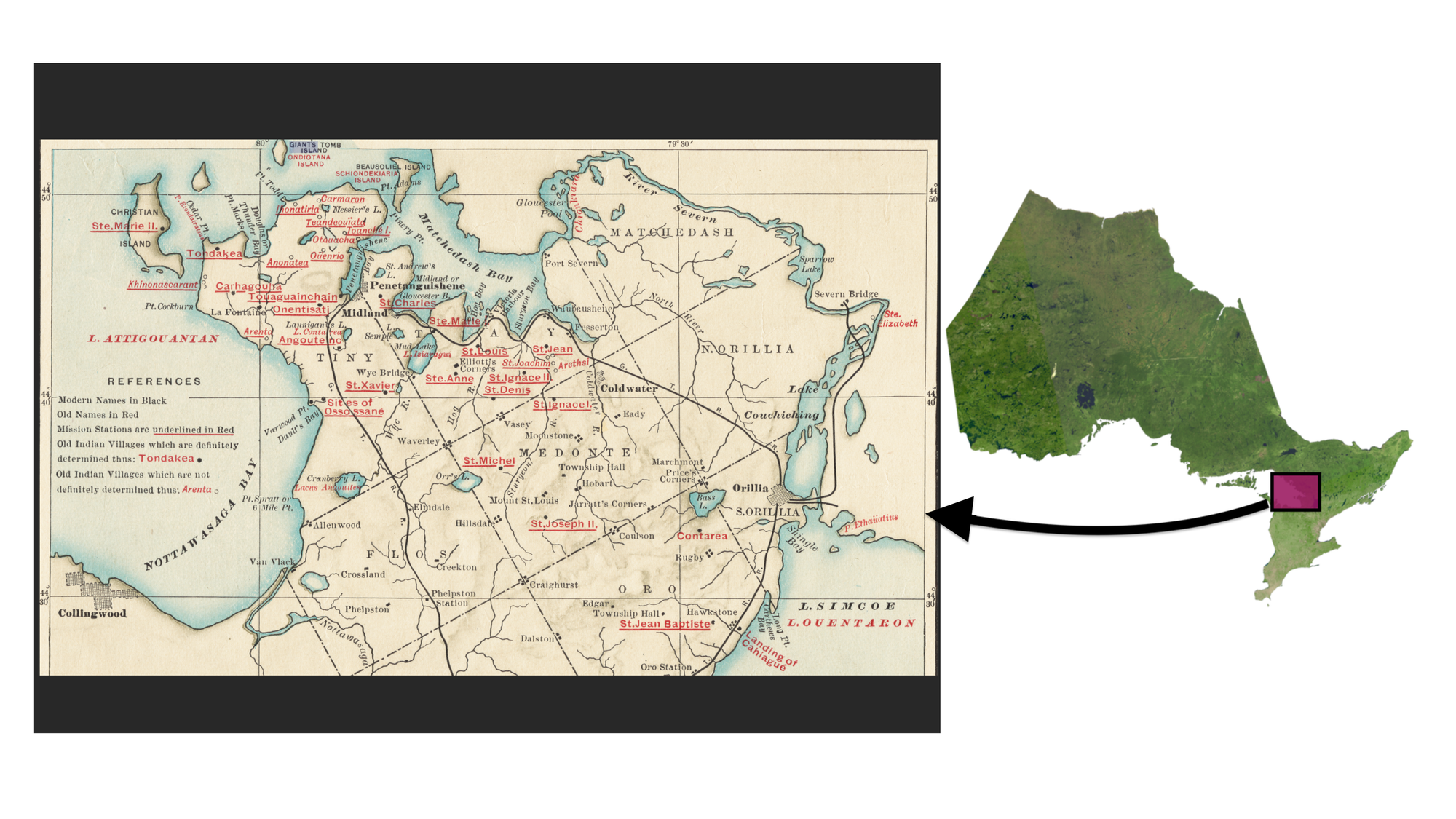

Le Jeune’s duties in Quebec prevented him from participating directly in the Jesuit mission to the Wendat Confederacy—in the area between what we now call Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay—which formed the cornerstone of the Jesuit religious/diplomatic project. But Le Jeune did hope to play a more central role in repairing relations with Quebec’s immediate neighbours to the north and east, the Innu.

Le Jeune decided to spend his first winter in Canada among the Innu rather than in the relative comforts of Quebec. He suspected that the Récollets had been too quick to give up on missionary work among these people, and opposed their plan to turn them into sedentary European-style farmers. In fact, Le Jeune believed that exposure to everyday secular French life in Quebec would undermine the Christian message. “Removed from all luxury” he explained, “they are not given to many sins.”

A bitter Canadian winter quickly dulled Le Jeune’s enthusiasm for life in northern Quebec. He complained that the tents the Innu lived in provided little shelter from the cold. Every night, half of his body was singed by his fire, and the other half frozen. Moreover, the rudimentary meals his hosts cooked didn’t agree with his French palate. At one point, the Superior was given a mixture of smoked meat and fish, ground together between two stones. The Innu had offered the meal as a rare treat, but Le Jeune was unable to hide his disgust as he ate it—which (understandably) did little to ingratiate him with his generous hosts.

Meanwhile, there was little sign that his preaching made much of an impact. Le Jeune had counted on help from Pierre Pastedechouan, an Innu man who’d been taken to France as a child by the Récollets, baptised, and extensively schooled in French and Latin. But Pastedechouan (who’d been called Pierre-Antoine during his years in Europe) claimed he was unable to translate the Superior’s religious ideas, prompting Le Jeune to accuse him of feigning ignorance to escape his duties.

After six frustrating months, Le Jeune returned to Quebec, having observed no measurable progress toward conversion, nor his own spiritual fulfilment. Describing his experience, he suggested that some ordeals were not worth enduring. “We can die but once” he explained. “The soonest is not always the worst.”

Like the Récollets, the Jesuits knew that bilingualism was a necessary (if not sufficient) precondition of missionary work. But they came to that project with opposite approaches. Having convinced themselves that the Algonquin and Iroquoian tongues lacked the capacity to express abstract Christian concepts, the Récollets focused on teaching French to prospective Indigenous converts. The Jesuits, however, believed that all languages—like all peoples—contained remnants of the divine. And so they were determined to preach in the language of their hosts.

The Récollet missionaries had produced a few Indigenous dictionaries and grammar guides. But the Jesuits found them deficient. They were also reluctant to use the French translators who’d been embedded within Indigenous communities as a means to build alliances and facilitate trade. Many of these men had remained at their posts during the brief English takeover, and so had betrayed the fact that their primary loyalty was to themselves and their Indigenous hosts, rather than to France. The restored French colonial authorities therefore saw them as unreliable.

The Jesuits also worried that these translators set a poor example of Christian behaviour—especially with respect to their relations with Indigenous women. And so wherever possible, the new regime pulled the translators out, and replaced them with salaried men loyal to the French trade monopoly that Richelieu had mandated, the Compagnie des Cent-Associés. As a result, Jesuit missionaries were often forced to learn the local Indigenous language from scratch.

Upon arriving in a community, Jesuit missionaries devoted themselves to long conversations with Indigenous partners. During this initial period, Jesuits were more students of language than teachers of religion. Le Jeune drew an analogy to algebra: Students had to learn the numbers one to ten before they could say anything meaningful about complex mathematical theorems. Another Jesuit expressed the problem in more practical terms. Relating the wisdom of Christ’s parables was impossible, he said, so long as the Jesuits had no way to describe everyday objects such as “casks of wine, lamps, or candlesticks.”

(The Jesuit missionaries ended up producing numerous manuscripts that detailed the words and grammar of several Indigenous tongues in their seventeenth-century forms. As these societies then relied exclusively on oral means of communication, these texts would prove extremely useful to modern Indigenous linguists seeking to strengthen—or, in some cases, resurrect—their languages more than three centuries later.)

The Jesuits soon realised that they would not only have to attain fluency in Indigenous languages, but also learn the respectful style of oratory that was prized within these societies. “If we could make speeches as they do,” Le Jeune observed, “and if we were present in their assemblies, I believe we would be very powerful there.” Time and again, Jesuit missionaries recorded their frustrations as they struggled to master such rhetorical subtleties.

The process required the Jesuits to deviate from the formal style of debate they’d learned in France, in which a premium was placed on mastery of facts and logic. But here in Canada, it was more important to demonstrate respect. To thoroughly refute and even humiliate one’s debating opponent, as Catholics and Protestants alike sought to do in their published tracts, was seen as vulgar. “There is no place in the world where rhetoric is more powerful than in Canada,” Le Jeune reported to his subordinates. “It controls all these tribes, as the [chief] is elected for his eloquence alone, and is obeyed in proportion to his use of it.”

Unlike most Europeans, the Jesuits believed that the barrier between the Old and New Worlds was not unbridgeable, and that there was a common humanity that connected the two—or, as the Jesuits would have put it, a common divinity.

Before going further, I should emphasise that I am not trying to portray the Jesuits as enlightened multiculturalists. Nor were they anthropologists in the modern sense. (Indeed, anthropology itself, as we know it, wouldn’t become an established field of study until the eighteenth century.) Ultimately, they believed that Catholicism was God’s chosen path for all mankind, and that every other belief system was false. The reason they spent so much time studying Indigenous culture wasn’t because they saw it as inherently fascinating, but because they believed that such research was a necessary step toward bringing these non-believers around to a “correct” understanding of mankind and God.

That said, I do think it is fair to treat the Jesuits as cultural relativists of sorts—at least by the standards of the day. Unlike most Europeans, they believed that the barrier between the Old and New Worlds was not unbridgeable, and that there was a common humanity that connected the two (or, as the Jesuits would have put it, a common divinity).

While the Jesuits were active among all of France’s Indigenous allies, including Innu and Algonquin First Nations, their main effort, as noted above, was directed at the Wendat Confederacy. Unlike the other groups allied with France, which followed the hunt in order to procure food and trade goods, the Wendat had a mixed economy and lived in farming villages. The Jesuits saw this more sedentary social structure as more compatible with the Christian world they knew back in Europe.

Leading the Wendat mission was a gifted student of language named Jean de Brébeuf. During the war with the English, he’d been recalled to the safety of Quebec, and ultimately, France. Among such reverse Jesuit exiles, none were more eager to return to Canada than Brébeuf. Thanks to his professional enthusiasm and unparalleled language skills, he was given the critical job of running the Jesuit operation within the Wendat homeland—known to Europeans as Huronia, and to the Wendat as Wendake.

The Récollet missionaries had found the Wendat tongue especially challenging—far more than the Algonquin variants they heard up and down the Ottawa River. Gabriel Sagard, the Récollet who’d spent the most time among the Wendat, claimed the task of mastering it was impossible. It is “a wild language,” he despaired, “almost without rules.” But where Sagard saw wildness, Brébeuf saw sophistication. And there was more than a hint of admiration in his observation that “they vary in their [verb] tenses in as many ways as did the Greeks.”

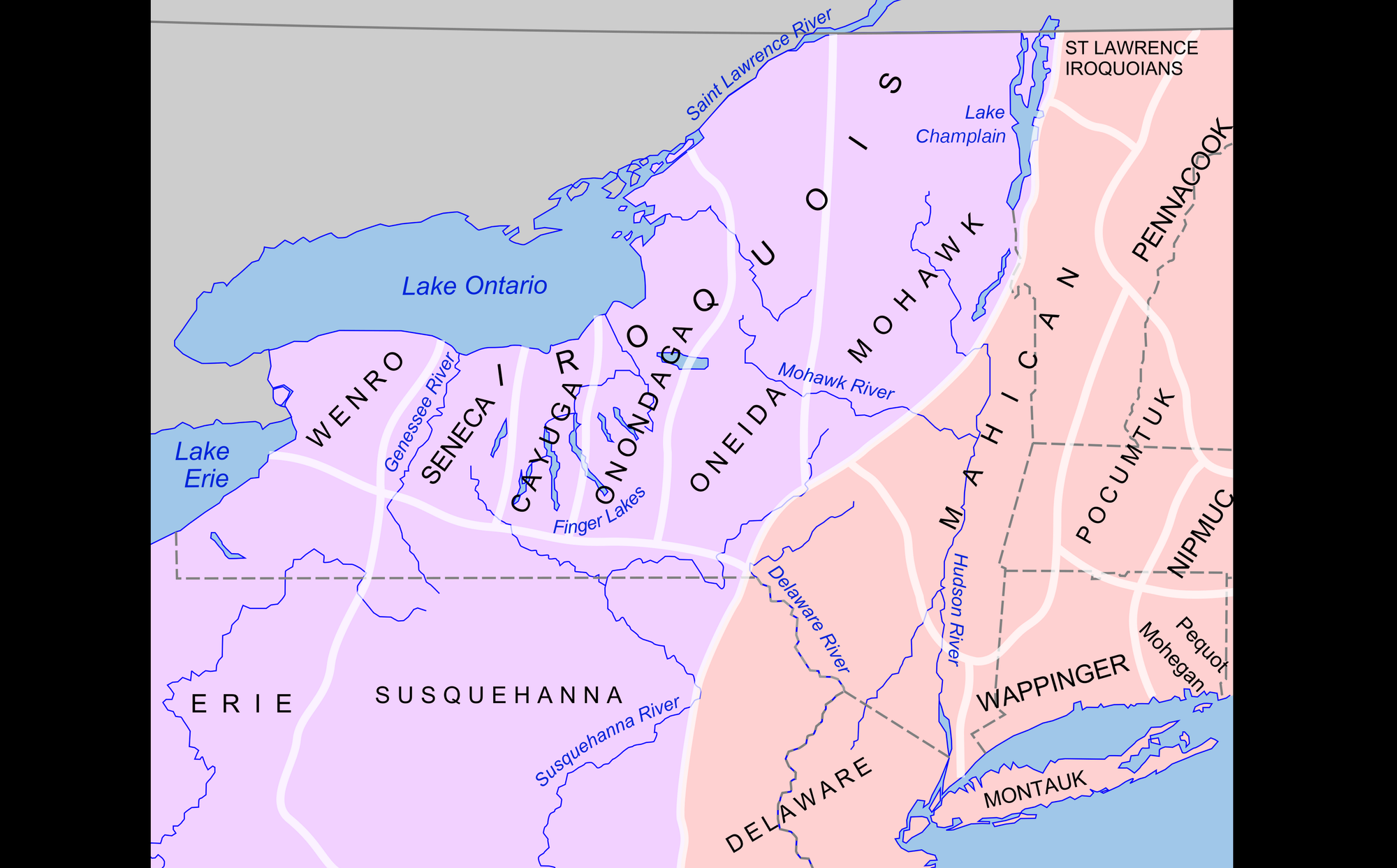

On the whole, both the Wendat and the Ottawa River Algonquins were eager to restore their pre-war alliance with the French—especially now that the Haudenosaunee (also known as Iroquois) had resumed their northbound raids. The security that the French alliance provided was more important than ever. However, those seeking to renew the coalition faced two challenges.

First, some of the Algonquins seemed tired of being the junior partners in what they saw as an alliance led by the two poles of the trade network—the Wendat in the west, and New France in the east. Indeed, some Algonquins had reached an understanding with the Haudenosaunee; especially the Mohawk in the east, who controlled access to Dutch trade on the Hudson River. In modern terms, they struck what might be called a free-trade agreement: Algonquin traders would help the Haudenosaunee trade into the Ottawa River/St. Lawrence network, while the Mohawk allowed these Algonquin traders access to Fort Orange (on the site of modern Albany, NY), the Dutch trading post on the Hudson.

In practical terms, little changed, however, as north-south trade between (what is now) modern Canada and upstate New York was difficult for geographic reasons. Even so, everyone had been put on notice that the Algonquins had their own interests to protect, and would not acquiesce indefinitely if others were taking them for granted.

A second challenge to the Laurentian Coalition became apparent in June 1633, just as the French began looking forward to what they hoped would be a record-breaking fur haul during the summer trading season. Champlain—now in his final years of life, but still in charge of the French operation at Quebec—received disturbing news: An expected convoy of Wendat traders making its way down the Ottawa River had halted, as some of the Wendat were expressing worries about what kind of welcome they’d get from the French. A Frenchman, living among the Wendat as a guest, had recently been murdered. In the recent past, relations between the French and Innu had soured following similar crimes, and the Wendat feared that history would now repeat itself at their expense.

The murdered man in question was someone we’ve met several times—Étienne Brûlé, the veteran translator who, by this time, had been living among the Wendat for more than twenty years. The circumstances of his death remain uncertain to this day, but the killing would cast a pall over the Franco-Wendat relationship for years afterwards.

It appears that Brûlé’s Wendat hosts suspected him of attempting to establish trade links with the Seneca—the westernmost of the Haudenosaunee nations, and a traditional Wendat rival. The forging of any kind of alliance between the French and the Haudenosaunee had long been a great fear of Wendat leaders. Back in 1615, readers may remember, Wendat chiefs went to great lengths to prevent Champlain from traveling west to visit the Neutral Confederacy on the Niagara Peninsula (a group that, as its name suggests, often acted as a kind of third-party mediator between the Wendat and Haudenosaunee). Later, in the 1620s, Récollet missionaries badly tarnished their reputation among the Wendat by trying to establish a mission among the Neutrals.

All of which is to say, the crisis of June 1633 wasn’t an isolated case of one group of Wendat traders having an argument in the middle of the wilderness. It was a symptom of distrust. The Franco-Wendat partnership was held together by a shared animosity toward (or, perhaps, fear of) the Haudenosaunee. The risk of destabilisation hovered in the background whenever signs emerged that the other side had reasons to defect.

Which raises the question: Why would Brûlé, who understood Wendat politics better than any Frenchman in the world, commit such an unforgivable diplomatic sin?

One possibility is that he was motivated by desperation. Before the war, he’d been unceremoniously dumped from his position as translator, and replaced in his capacity as official French representative by Jesuit missionaries. The brief English occupation of Quebec in the early 1630s had been his ticket back to prominence, as he returned to his role of managing the Wendat convoys that travelled to the St. Lawrence every year.

Now, however, he risked being sidelined; or, worse, accused of wartime treason because he’d collaborated with the English. And if he was no longer welcome on the St. Lawrence, what was his role in Wendat society?

Scrambling to seize upon whatever options remained to him, Brûlé may have thought back to the winter of 1615–16, when he went on an epic trek to visit Indigenous nations inhabiting the mid-Atlantic coast, to drum up support for Champlain’s latest raid into Haudenosaunee territory. That diplomatic mission failed. And on the return trip, Brûlé’s party was ambushed as it tried to slip through Seneca territory. Recognising the potential value of a French alliance, the Seneca took Brûlé captive rather than killing him.

At the time, expanding French trade into Haudenosaunee country would have been reckless, so Brûlé had not followed up with his Seneca contacts. But now, he was desperate enough to try anything.

It’s possible that he hoped to reconcile himself to the new regime in Quebec by proving his usefulness. Establishing trade with the Haudenosaunee would open up new markets for the French, and perhaps even improve the security of the St. Lawrence. From the very beginning, Champlain had seen a general peace in the region as a boon to French interests—even if war with the Haudenosaunee had initially been useful for building alliances with the Wendat, Algonquins, and Innu. (As I’ve noted at several junctures, Indigenous societies typically saw trade flows and military alliances as going hand in hand.)

Or perhaps Brûlé feared that he’d burned his bridges with the French. His only hope now was to forge a new partnership with the Dutch traders on the Hudson River. If he could develop a trading network with the Seneca, he could expand Dutch influence (now largely limited to the Hudson Valley) into the Midwest—in effect, recreating his influential role in the old French network.

Whatever Brûlé’s intentions, his Wendat neighbours turned on him once his dealings with the Seneca were discovered. But his murder in 1633 was the act of a few individuals, not the product of any kind of group consensus. In fact, the incident immediately sparked a bitter division within Wendat politics. Some feared that killing a Frenchman (something no Wendat had ever done before) would ruin the alliance. As the Innu had learned, the French did not treat homicide as a crime that could be adequately redressed through the customary gifts of condolence that Indigenous nations typically exchanged. Rather, Champlain had made it clear that a Frenchman’s blood could only be repaid with the blood of his killers.

Other Wendat leaders were more optimistic, however. They argued that Brûlé was a traitor. The French would thank them for punishing his betrayal. And even if they didn’t, the needs of national security had demanded Brûlé’s death. Since when did French interests trump those of the Wendat?

This conflict wasn’t resolved when the 1633 trading season kicked off—which is why that Wendat convoy found itself in limbo, unsure of what kind of reception the traders would receive from the French. Seizing the opportunity to gain political leverage, the Algonquins on the Ottawa River played up the tension. They reported that Champlain was in a rage, and that the French had laid an ambush—a complete fabrication.

The stand-off was finally broken by Amatacha, the son of a Wendat chief who’d spent time in France earlier in his life. He travelled to Quebec personally to relay the news of Brûlé’s death and then gauge the response. Champlain informed Amatacha that Brûlé (like Nicolas de Vignau, whose story we covered in our fifteenth instalment) had forfeited the protection of the French Crown, and so his killers had nothing to fear in Quebec. Amatacha returned to the convoy with the good news, and the trading convoy recommenced its journey. But the underlying sense of distrust would persist.

The immediate question was who would replace Brûlé as the primary French representative in Huronia. The Wendat traders on the St. Lawrence wanted Champlain to send armed Frenchmen, who could help protect their settlements from Haudenosaunee raiders. But Champlain firmly insisted that the Jesuits would now be acting as France’s ambassadors.

Disappointed—and possibly influenced by dubious Algonquin claims that the Jesuits were at deadly risk if they travelled through their territory—the Wendat explained that it would be impossible to bring any priests back to Huronia until their safety could be assured. They also said that accepting the Jesuits would be up to the Confederacy Council, not mere traders. As a result, Brébeuf and the other Jesuits would have to wait another year before they could set up their mission.

Meanwhile, 1633 was an eventful year south of the St. Lawrence, too. Back in 1628, readers will recall, the Mohawk had successfully displaced the Mohicans on the Hudson River, giving them a monopoly on Dutch trade goods. For their part, the Dutch attempted to emulate the French by forming a mutually beneficial partnership with their Indigenous neighbours. But they found that the geopolitics of the Hudson Valley were quite different from those on the St. Lawrence. While the Wendat homelands were far removed from Quebec, the Mohawk were in a position to exert direct military power against the Dutch trading post at Fort Orange. As we saw in the twenty-first instalment, the resulting encounters could sometimes be lethal.

As the French and Wendat tentatively renewed their friendship on the St. Lawrence in the summer of 1633, a newly arrived Dutch commander at Fort Orange, Hans Jorissen Hontom, responded to Mohawk complaints about Dutch trade practices by kidnapping a Mohawk chief and publicly torturing him to death. This attempt to reverse the balance of power in the region backfired spectacularly: In October, Mohawk warriors raided Fort Orange, burning all the Dutch ships on the river, and killing the trading post’s livestock. The Dutch did not retaliate, as their rudimentary trading colony simply didn’t have the resources to wage war. It was obvious that the Mohawk still ran the show in the region, and that any trade on the Hudson would be conducted on their terms.

This Dutch subplot is important to our own narrative because it shows why some Algonquin groups looked south for new partnerships: The Mohawk now presented neighbouring Indigenous societies with an alternative source of European goods. Despite the appearance of two opposing blocs—the northern Laurentian Coalition versus the southern Dutch-Mohawk dyad—the diplomatic situation in the region had become as treacherous and complex as the dynastic rivalries that Champlain once observed in Europe.

Even by the spring of 1634, the diplomatic situation on the St. Lawrence remained tense, as the Wendat had still given no formal indication that they were ready to accept the Jesuits. But Brébeuf and a fellow Jesuit, Antoine Daniel, were tired of waiting. The pair struck a clandestine deal with a group of Wendat traders to smuggle them into Huronia.

These traders were rolling the dice, not only because they risked angering their leaders back home, but also because Brébeuf and Daniel were inexperienced travellers—dead weight in their canoes should they encounter any trouble while paddling up the Ottawa River. On the other hand, the traders also had much to gain if the gambit succeeded, since they’d be owed a debt of gratitude from these evidently influential and highly respected French emissaries.

The greatest danger came when the travellers hit the Kitchespirini-held choke point at Morrison Island (whose strategic significance we examined in our sixteenth instalment). During one of the portages, Daniel struggled to keep up with the rest of the group, and was left behind. He quickly became lost, and may even have been assaulted by a group of local Algonquins. Eventually, however, he linked up with another group of Wendat travellers, and followed Brébeuf upriver—a development that seemed to cast doubt on Algonquin claims that priests travelling in the area would face deadly peril.

By August, Brébeuf and Daniel were in Ihonatiria, a newly established Wendat village. Despite not pre-approving the Jesuits’ arrival, the Wendat Council had little choice but to accept their arrival as a fait accompli. To refuse these men hospitality would be a serious affront to the French.

The arrangement was formalised on the St. Lawrence the following summer, when a group of Wendat chiefs accompanied the main 1635 trading convoy, and paid their respects to a (now ailing) Champlain. The French colonial leader then tried to push things a step further by claiming that future trade would be contingent on the conversion of Wendat society to Christianity within four years. The Wendat chiefs agreed that they would listen to the teachings of the Jesuits. After all, it wasn’t out of the ordinary in the Indigenous world for allies to learn from one another. On the other hand, the Christian idea of full-blown conversion—insofar as it entailed the outright rejection of Indigenous traditions—was not likely a concept they fully grasped at this point.

The Algonquin wing of the Laurentian Coalition also stabilised during this period. The rumoured partnership between the Haudenosaunee and Algonquins had (for both sides) always been a politically useful diversion more than a reality—as brutally demonstrated by events that took place in the summer of 1635. A Kitcherspirini chief had decided to take the Haudenosaunee up on their attempts to peel the Algonquins away from the Laurentian Coalition, and sent a group of Algonquin traders to the Hudson. The Mohawk caught the visitors and butchered them outside Fort Orange. In response, Algonquin tribes turned to their traditional allies to come to their aid, and Algonquin attempts to obstruct French travel on the Ottawa River were lifted.

Thanks to the formal acceptance of the Jesuits in Huronia and the horrifying end to the Haudenosaunee-Algonquin diplomatic flirtation, the Laurentian Coalition was restored to its 1620s form. Although tensions remained, and trust was never entirely absolute, the region once again took on the appearance of two rival blocs, one on either side of the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes.

Next time around, we will examine a new threat that France’s Indigenous allies will face—one far more deadly than any Haudenosaunee war party. For their renewed friendship with the French had brought an ancient scourge—infectious disease.