Nations of Canada

United Against the Iroquois

In the fourteenth instalment of his series on the history of Canada, Greg Koabel describes Champlain’s military alliance with France’s new Innu, Algonquin, and Wendat trading partners.

What follows is the fourteenth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialized Quillette project adapted from Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name.

We left off our last instalment in 1609, with French cartographer-turned-military-adventurer Samuel de Champlain executing a daring plan to save the French colony of Quebec, on the St. Lawrence River—though “colony” is putting it generously. In the Fall of 1609, when Champlain headed back to France to plead his case with King Henri IV and his court officials, Quebec (modern Quebec City) had been in existence for little more than a year. Only a handful of colonists had survived the previous winter. And unless funds could be raised to supply its residents with the necessities of life, Quebec was unlikely to survive 1610.

The main problem was money. The king—advised by his tight-fisted first minister, Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully—refused to invest state funds in the enterprise. Henri had been willing to support Quebec by granting a monopoly on the fur trade to Champlain’s predecessor, with the resulting profits going to sustain any supporting colony. But after five years of poor management and minimal returns, the king revoked that monopoly, opening up the fur trade to independent dealers (many of whom had been flouting the monopoly anyway).

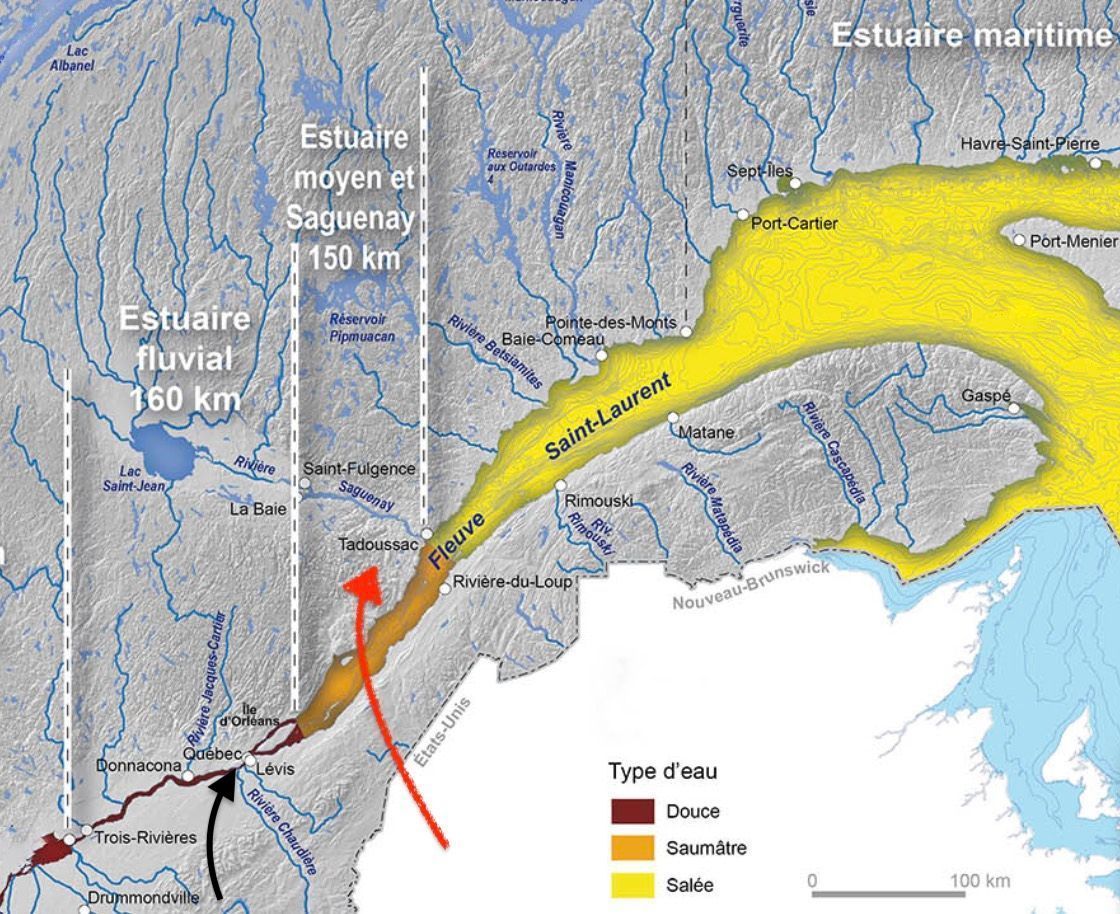

The problem, as Champlain saw it, was that the monopoly had little value to offer so long as the main centre of trade was at Tadoussac, more than 200 kilometers northeast of Quebec, near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. On its shoe-string budget, the company (as the monopoly was known) could do little to stop the local Innu population from selling furs to whoever put in at port—including the plucky Basques, who’d been developing Indigenous trade contacts for several decades.

The Innu were proving to be skilled traders, and recognized the value of a competitive market. In some cases, they found ways to hold back their annual supply until a critical mass of European vessels arrived in the Spring for this reason. It went against their interests to support a single group—French or otherwise—that held monopoly power over prices.

Champlain’s solution was to move the primary centre of fur exchange further up the St. Lawrence, to Quebec. A renewed monopoly-holding company could control access along the St. Lawrence at this much narrower choke point. (As previously noted, the word “Quebec” follows the Algonquin word for “where the river narrows”— kebec.)

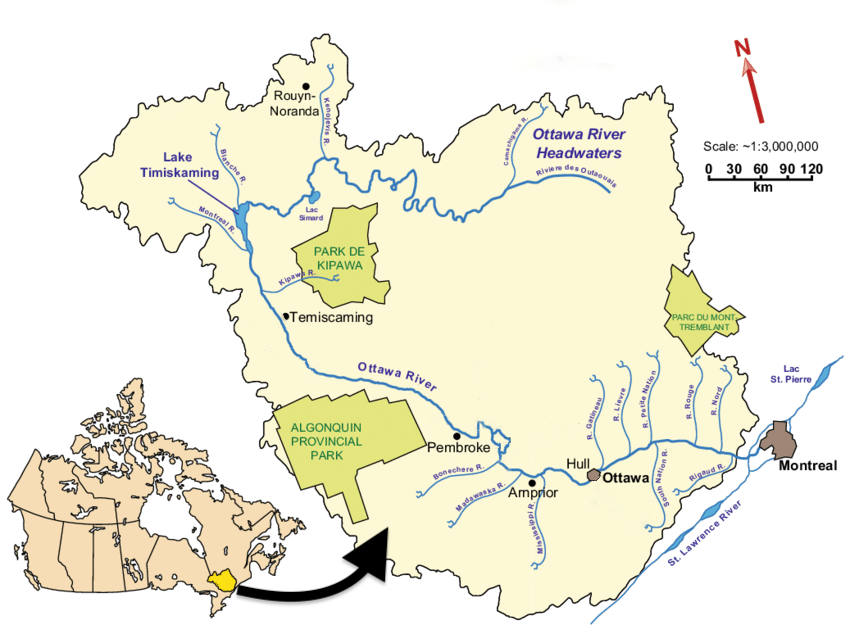

At this point, the river is less than a kilometer wide, as compared to more than 20 kilometers at Tadoussac. Moreover, a Quebec operation would allow the French to tap into a larger source of fur, encompassing the whole of the St. Lawrence basin; while at Tadoussac, the Innu supply was limited to the smaller Saguenay River basin.

To achieve this pivot, the French would have to establish trade relationships with the Algonquin nations that lived along the Ottawa River, which fed into the St. Lawrence just west of the great rapids located near modern Montreal; as well as the Wendat (whom the French would call Huron), who controlled a vast trading network further inland, extending well into modern Ontario. The value of the revitalized French monopoly company would be based primarily on the diplomatic relations that Champlain developed with these new fur suppliers—and not on high-seas gunboat diplomacy with rival Europeans.

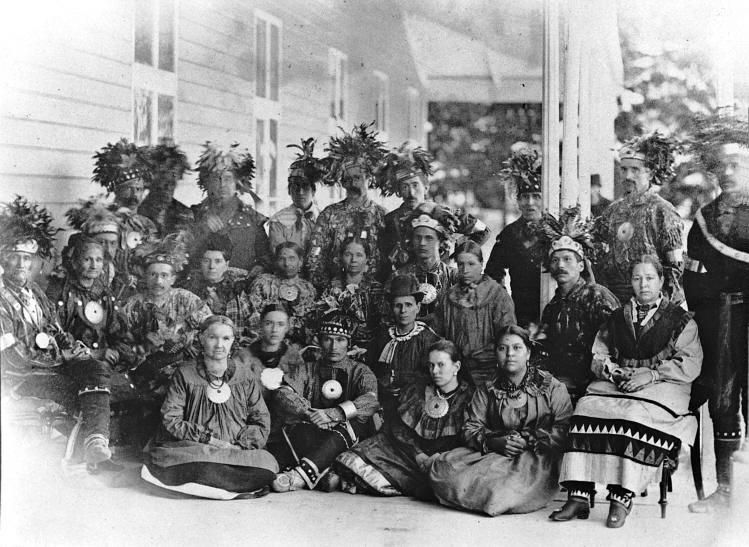

As recounted in the last instalment, Champlain began this process in 1609 by setting out with a party of Innu, Algonquin, and Wendat warriors as they raided south into the territory of their common enemy, the Iroquois (in the process, venturing through the lake that would one day bear Champlain’s name). In the Indigenous world, as we’ve seen, war and trade went hand-in-hand.

By participating in what proved to be a victorious campaign, Champlain won two key promises from his comrades. First, they would bring furs to the St. Lawrence to trade the following summer. And second, that they would guide Champlain northwest, up the Ottawa River, and show him what lay beyond the great rapids. This partnership between Champlain and his new Indigenous friends was the foundation upon which France’s new fur monopoly would be built.

Upon his return to France in late 1609, Champlain immediately sought out his partner Pierre Dugua de Mons, the aristocratic entrepreneur who’d been doing his best to keep the colonial project financed. For de Mons, the diplomatic progress Champlain had made with Indigenous groups was welcome news. For the last year, he’d been keeping the Quebec colony on life support through a mixture of calling in favours and tapping his personal savings.

De Mons managed to convince a group of merchants in Rouen, the main port city serving Paris, to help finance the maintenance of Quebec in exchange for allowing them to use it as a fur warehouse during the next fur trading season. Most traders had been hesitant to take their ships beyond Tadoussac. But if they had access to a permanently manned storage facility upriver, the risk and expense of trading inland would both be lessened. So it was that Quebec began its commercial life, rather ingloriously, as a storage hub.

For its part, however, the French Crown remained unconvinced that a renewal of the monopoly was justified. Independent traders had complained that a monopoly would actually hinder French trading fortunes, to the advantage of the English, Dutch, and Spanish rivals who flouted the French king’s pronouncements. What benefit would there be to the French nation if its merchants battled each other in the courts while foreigners enriched themselves?

And so when Champlain sailed back to Canada in the Spring of 1610, his company still had no monopoly. Its salvation would have to be won the hard way, on the St. Lawrence, before its corporate preeminence could be ratified in Paris.

By the end of April, Champlain was in Tadoussac, where the harbour was already full of European traders. For the second year in a row, there was no monopoly—not even a nominal one—restricting who could trade. Innu middlemen and European adventurers of all kinds were engaged in a free-for-all.

The more experienced European merchants were well aware of the commercial power that Innu chiefs could exert. Back in Europe, capitalism (as we would now call it) was cold and impersonal. But on this side of the Atlantic, the provision of generous gifts and the forging of strong personal relationships were crucial means to secure preferred access to furs. Indeed, the history of this period shows that European traders adapted to Indigenous commercial practices just as much as vice versa.

The winter had been a good one for Indigenous hunters in this region, and Champlain saw none of the desperation and hunger that had been in evidence a year earlier. That was good news for Quebec, which Champlain learned had survived the winter in much better shape than the 1608-09 season—thanks, in part, to the aid of the settlement’s Indigenous neighbours.

The Innu welcomed Champlain’s arrival, as memories of the Frenchman’s military aid in 1609 were still fresh in their minds. Not since the great victories of 1603 had they enjoyed such security on the north shore of the St. Lawrence. And their Iroquois rivals would soon learn that the previous year’s raid hadn’t been a one-off affair. The balance of power in the region was shifting.

Champlain happily confirmed his intention to once again make war with his friends that summer. But he also reminded his Innu hosts of their promises: He looked forward to exploring the northern reaches of the Saguenay River with the aid of Innu guides. Champlain was interested in seeing the source of all those furs the Innu traded at Tadoussac.

Most of all, he wanted to visit the great northern sea that he’d heard rumours about. Previous attempts at exploring the area north of Tadoussac had been met with polite refusals from the Innu, coupled with ominous warnings about the fierce and hostile nations that supposedly populated the upper Saguenay. Champlain had suspected that these were diversionary tactics. Both sides knew that the establishment of direct contact between the French and the Algonquin fur trappers of the north would threaten the Innu status as essential middlemen.

After a few days, Champlain made his way up the St. Lawrence, toward Quebec, and invited an Innu war party to follow him a few weeks later for another raid into Iroquois territory. The goal, once more, was to assemble a joint force of Innu, Algonquin, Wendat, and French warriors. Historians came to refer to this alliance as the “Laurentian Coalition,” after the St. Lawrence River, which linked its members.

As a meeting point, Champlain chose an island in the mouth of what is now known as the Richelieu River—the fourth great river, alongside the St. Lawrence, Ottawa, and Saguenay, whose contours would define the patterns of French colonial operations for many decades to come. While Champlain checked on the colony at Quebec in May, large numbers of Algonquin and Wendat canoes were already arrived at the Richelieu. Some crews had come merely to trade, but others intended to stay until the coalition war party assembled.

The sight of this kind of brisk fur trade being conducted so far upriver was encouraging to Champlain. But there were also a few problems in evidence. First, notwithstanding Quebec’s geographical advantages as a choke point for European vessels, the colonists at Quebec still had no way of stopping independent traders from flooding upriver. The Rouen merchants with whom de Mons had made his deal with were there. But so, too, were independent traders, drawn by rumours of a new, untapped market. As they discovered, these rumours were true.

A greater problem was the culture clash emerging between French traders and the Algonquin and Wendat suppliers who’d brought their furs to the St. Lawrence. The French were used to dealing with the Innu at Tadoussac, and assumed this would be more of the same. But the Algonquins and Wendat had their own customs.

Unlike the Innu, moreover, these new suppliers weren’t yet accustomed to the aggressive, impersonal, grasping nature of European capitalism. The French rudeness on display was, in a word, a turnoff. Most of the Indigenous traders had come to the Richelieu to deepen their relationship with Champlain, and so were mystified by the behaviour of his French countrymen.

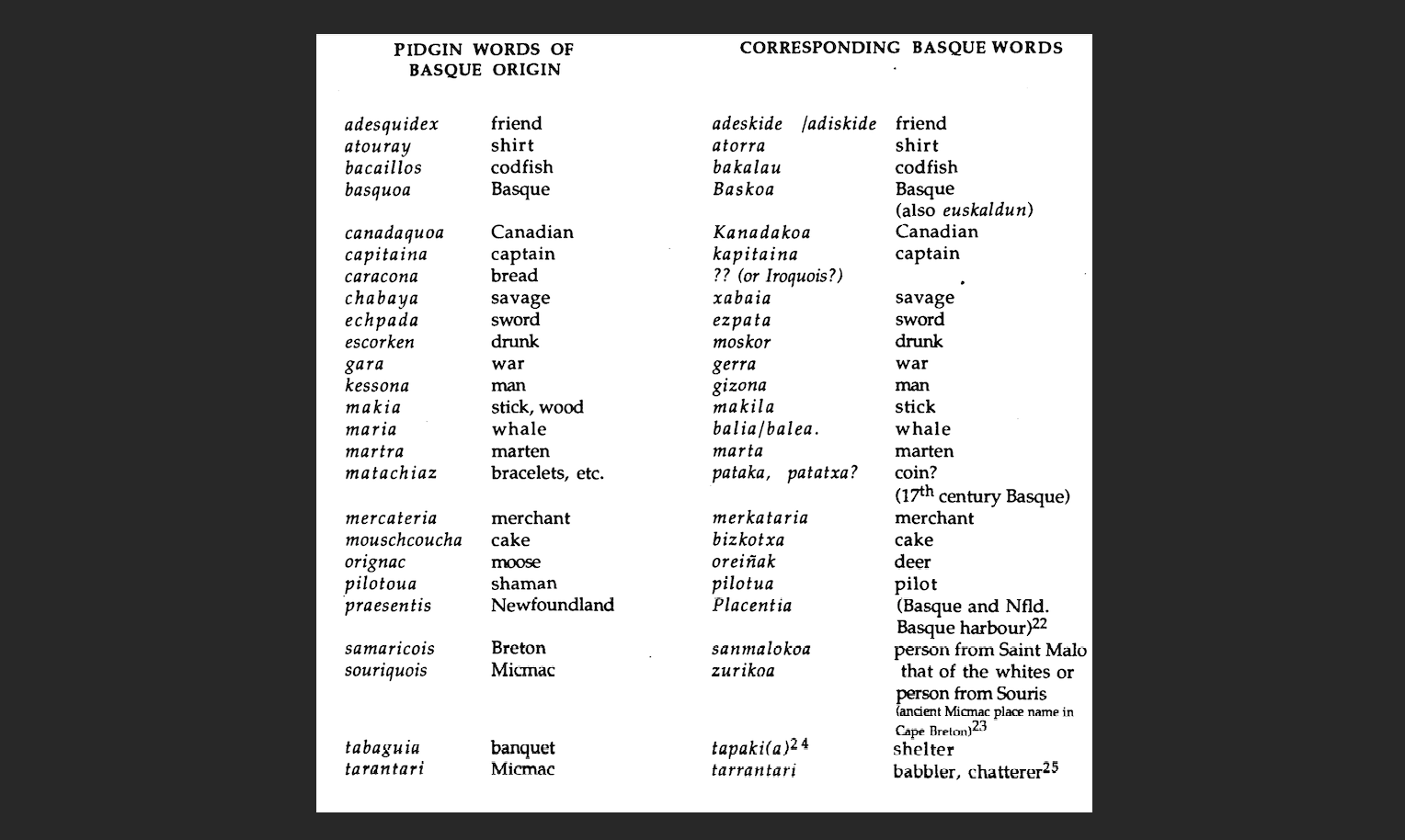

Language was another problem. With the Innu, the business of buying and selling was mediated through a kind of hybrid trade tongue that combined elements of Innu Algonquin, Basque, and French. This trade pidgin was so ingrained that some European traders came to believe (wrongly) that it was the native language of the whole region, and were confused when the Wendat did not understand it.

There was also a significant gap when it came to economic incentives. Unlike the Innu, the Wendat hadn’t yet geared their society to the fur trade. For generations, they’d presided over their own intra-Indigenous trading network that encompassed Algonquin-speaking neighbours to the north and the east, as well as Iroquoian-speaking nations to the south, such as the Neutral Confederacy and the Petun Nation in what is now southwestern Ontario. Trade with Europeans was seen as a welcome new opportunity, as the French had unique and valuable goods to offer, and Champlain’s proposed military alliance promised greater security. But these were arrangements that the Wendat Confederacy would only embrace on its own terms: The Wendat had been thriving before the arrival of European goods, and most of its leaders were confident they’d do just fine whether or not they began trading for French products.

Which is to say that the Wendat hadn’t come to the St. Lawrence in desperate need of buyers. Rather, they were giving Europeans the opportunity to impress them—much as a well-heeled investor might survey the offerings at a modern trade show. And so far, the French traders weren’t making much of an impression.

But fate conspired to bail out these ill-mannered French parvenus, in the form of news that a large group of over 100 Iroquois warriors had been sighted coming down (i.e., travelling north along) the Richelieu River. These men hailed from the easternmost Iroquois nation—the Mohawk. They were looking to avenge the military raid of 1609, during which Champlain and his two French subordinates had personally shot down a group of Mohawk war chiefs.

The warriors among the Wendat and Algonquin traders mobilized quickly, and paddled their canoes southward, up the mouth of the Richelieu. The French traders, on the other hand, had no interest in risking their lives in what they saw as an incomprehensible foreign conflict. From a European perspective, it was a sensible move. Yet it was seen as a grave insult to their would-be Indigenous trade partners: How could they sell furs to men who rejected a corresponding strategic alliance?

Champlain’s convoy was alerted to the presence of the Mohawk warriors at almost the same time. The Innu warriors manning these canoes rowed hard, and arrived at the battle soon after it had begun. At this point, the French and Innu disembarked in the middle of a confusing scene. The sounds of battle were all around them, and the Innu warriors raced ahead, leaving Champlain and his handful of musketeers behind. Seventeenth-century firearms were not designed for transport and use in North American woodlands. The Frenchmen, laden down with guns and ammunition, struggled to keep up.

Eventually, Champlain arrived at the centre of the action, and took part in the final victory. The Mohawk warriors had spotted the approaching enemy and thrown up a makeshift barricade of logs and branches. By the standards of warfare on the St. Lawrence, this Mohawk war party was quite large, and so they’d assumed a strong defensive position would scare off any attack.

Unfortunately for the Mohawk warriors, they were outnumbered, having stumbled across a four-way coalition. It was extremely rare for such a large group of Wendat to travel so far from their homeland near Georgian Bay, and they were accompanied by delegations from several nations along the Ottawa Valley. The Innu and French reinforcements that arrived late in the day only made the order of battle more lopsided.

As with most other aspects of his adventures, Champlain documented the fight, which came to be known as the Battle of Sorel. He estimated that over 100 enemy warriors were killed, with 15 taken prisoner. None are known to have escaped. Casualties among the coalition forces, on the other hand, were light, though Champlain himself received a superficial wound to his neck from an arrow. (A slightly better-aimed shot would have radically altered the course of North American history.)

While the size of the Mohawk force may seem small by the standards of modern military engagements (or even by the standards of seventeenth-century European skirmishing), the loss of so many warriors—men in the prime of their lives as hunters, fighters, and fathers—would have been catastrophic to the Mohawk. Combined with their losses at the Battle on Lake Champlain the year before, they’d lost perhaps 15% to 20% of their men of fighting age. And it would be another twenty years before Iroquois raiders again threatened the St. Lawrence.

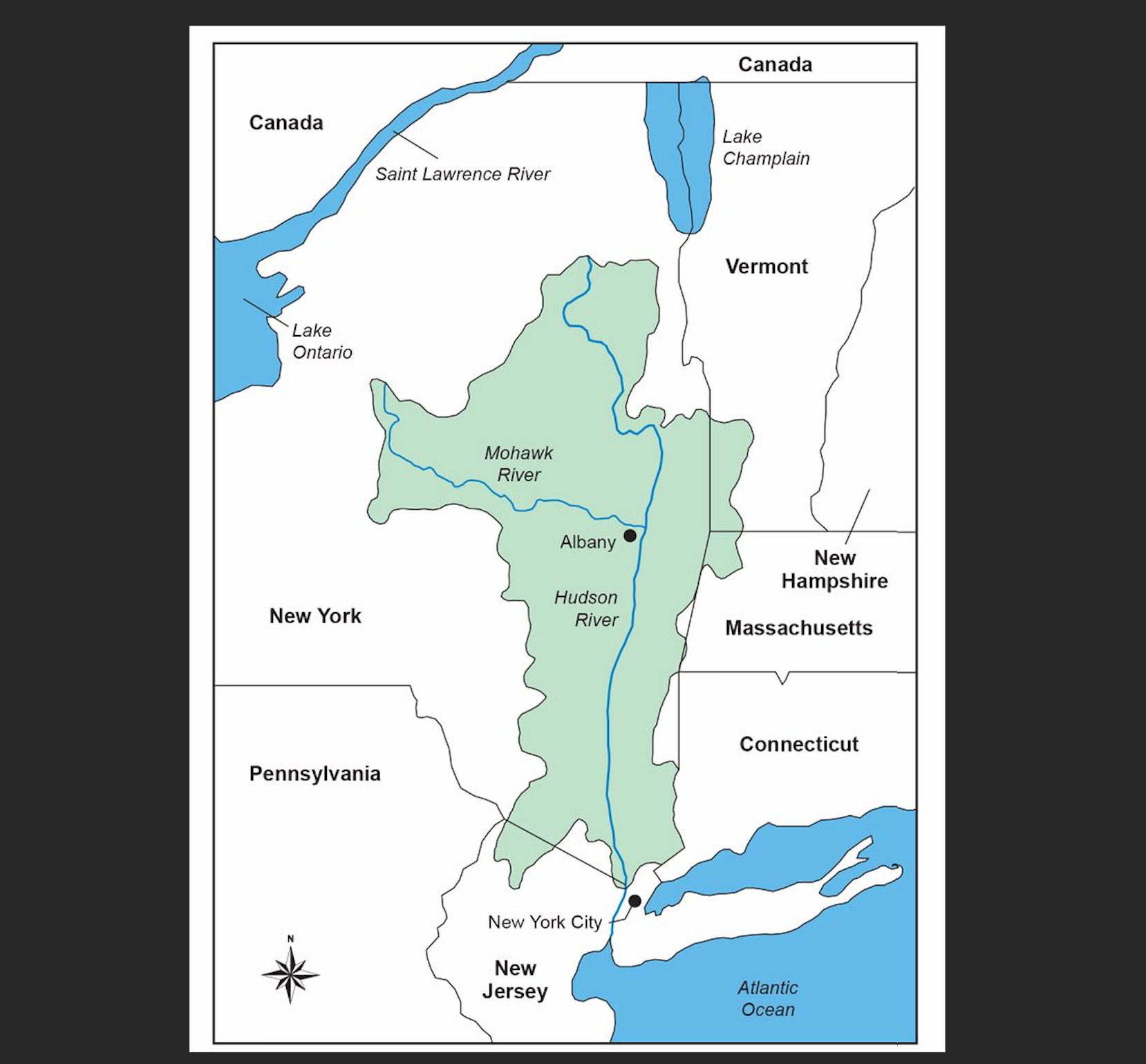

As things turned out, the Iroquois had other reasons for temporarily retreating from the St. Lawrence—as this wasn’t the only river that could bring European goods into the North American interior. The previous summer—just weeks after Champlain had battled Iroquois warriors on Lake Champlain—Henry Hudson, an English explorer in the employ of the Dutch, had found a new access point to the fur trade, further south. The Hudson River, as it would later be named, ran from the edge of Mohawk territory to the island of Manhattan. Dutch traders who followed Hudson up his river would establish a trading post known as Fort Orange—modern-day Albany—just miles from Mohawk territory.

In the following years, the Iroquois (and the Mohawk especially) would not so much retreat from the St. Lawrence as re-orient themselves toward the Hudson to the southeast. And they would never again make the mistake of using traditional Indigenous military tactics against their European-backed enemies to the north. A close relationship with the Dutch, who of course had their own European military technologies to share, would help fuel the revolution in North American warfare that Champlain had already started.

In the meantime, the victorious Laurentian coalition had its own internal challenges to face, which, once again, emerged from differences between European and North American cultures. The Indigenous warriors were disgusted with the behaviour of the Europeans, who looted the bodies of the dead for their valuable furs. For their part, the Europeans were horrified by the torture and execution of captured enemy soldiers.

Because the common threat faced by all four parties to the coalition had now been neutralized, members began to assess how the new status quo affected their own interests. The Innu, in particular, had much to lose from a St. Lawrence that was secure from Iroquois raids; as the economic centre of gravity would inevitably shift from Innu-controlled Tadousac to the upper St. Lawrence. This geographic shift worked to the relative benefit of the Wendat, and the Algonquins along the Ottawa River.

It would take time for these divergent interests to develop into real political divisions, however. And in the immediate aftermath of the battle, Champlain’s first concern was nailing down the concessions he’d been promised: Like the Innu, the Wendat and Algonquins had promised Champlain a tour of their lands.

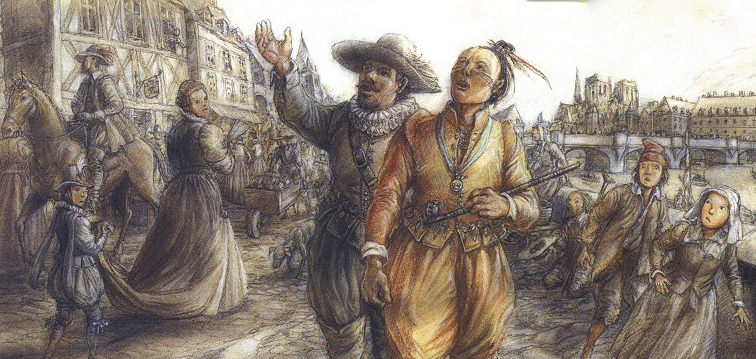

Originally, the French explorer had wanted to chart the Ottawa River and the other areas beyond the great rapids himself. Instead, he agreed to send Étienne Brûlé, an 18-year-old in Champlain’s entourage who’d volunteered to spend the winter with the coalition allies. At the same time, Savignon, the younger brother of a Wendat chief, would return to France with Champlain over the winter. This swap of young men was a traditional method of building friendly relations between nations in Indigenous culture.

The details of this exchange revealed the fairly complicated nature of the Laurentian coalition. Brûlé would be hosted by Iroquet, the Algonquin chief whom Champlain had partnered with during his original 1609 raid. But although Iroquet’s Onontchataronon nation was based in the Ottawa River valley, it had a close trading relationship with the Wendat Confederation, and usually spent winters in Wendat territory. So although Brûlé was technically joining an Algonquin nation of the Ottawa River, he’d end up spending most of his adult life in Huronia (the French name for the Wendat homeland). In fact, Brûlé would become the first European to see what lay beyond the great rapids, and would play a key role in Franco-Indigenous politics.

When Champlain landed back in France in September 1610, he was greeted with bad news: On May 14, just a few weeks after Champlain had sailed for Canada, King Henri IV, the 57-year-old monarch, had been assassinated by a Catholic religious fanatic on the streets of Paris. The France that Champlain returned to was now governed by a regency council, acting in the name of Henri’s son, the nine-year-old Louis XIII.

Beyond the general disruption such a dramatic change in government could cause, the new political landscape presented some specific challenges for the Canadian colonists. Although Henri IV had never offered much in the way of financial support, he’d been interested in promoting France’s colonial ambitions in other ways. On several occasions, he’d flexed the soft power of the Crown to cow opposition to the project from rival merchants and court officials. With his death, it was no longer clear who (if anyone) would provide moral backing at court.

The second problem facing the Canadian project was religion. From the outset, the Huguenot (i.e., Protestant) merchants of France’s ports had played an outsized role in North Atlantic commerce. Champlain was (like the old King) a native Protestant who came to the Catholic Church through conversion. And de Mons, the man at the top of the would-be monopoly company, was an open and prominent Huguenot. While King Henri reigned, this hadn’t been a huge problem. His vision of France as a Catholic nation that tolerated a Protestant minority had room for Huguenot colonists. But how long would that vision hold now that he was gone?

There were troubling signs that the new regency council would move France in a decidedly hard-line Catholic direction. The dominant force on the council was the Queen Mother, Henri’s widow, Marie de’ Medici. As her name suggests, she came from the influential Italian Medici family, and on her mother’s side was related to the Hapsburgs. Her circle of advisors included a number of Italian clergymen, and there were early signs that the regency council was moving toward a reconciliation with Hapsburg Spain—France’s traditional (ultra-Catholic) rival.

Shortly after the king’s death, de Mons was removed from his various offices in the royal household—severely limiting his influence at court. His career as a lobbyist was now over. Nor was Champlain able to achieve much. His family’s service to the old king during France’s civil war had always granted him personal éntree with Henri. But with the regency council, he had no such standing.

As for Champlain’s Wendat guest, Savignon, he found life in France frustrating. To his eye, French men seemed insufferably effeminate: They would often quarrel, but seldom came to blows—a sure sign of cowardice. Savignon was also disgusted by the widespread use of corporal punishment, which was common in all European societies. He was shocked to see criminals tortured in public demonstrations, a practice reserved for war captives back in Canada.

Savignon reserved his greatest condemnation for the use of violence against children, a then-normal part of European education that was entirely absent from Indigenous parenting practices. (Savignon probably witnessed this first-hand: As he had come to Europe partly to learn French, he may have found himself in the company of schoolchildren.) Upon his arrival back home, he advised his friends and family to avoid visiting France; it was a nasty, brutal place.

Back in Canada, meanwhile, the young Étienne Brûlé had an opportunity to study the Wendat Confederacy, on whose territory he spent the winter. Generally speaking, these Indigenous confederacies were extremely decentralized by the standards of modern states. The constituent nations exercised full autonomy in internal matters, and even foreign policy. The primary function of the Confederacy was to govern relationships among members. Disputes could be resolved at Council, rather than through violence.

In theory, therefore, the relationship with the French was not a matter that required the attention of the Council. The laws and customs regarding trade alliances were fairly well-established. Over time, in fact, the Wendat had developed a system that bore some resemblance to European monopoly companies: Whoever established a new trading relationship with an outsider earned the exclusive rights associated with that trade. In practice, this usually meant sharing the fruits of that commerce with one’s wider kinship group, as well as with outsiders who might be included following their offer of suitable gifts.

But the sheer size and political significance of the French alliance forced the Wendat Confederacy to treat this relationship differently. Over the winter of 1610-11, a special session of Council was held, to determine how to manage this new opportunity.

One of the practical problems facing Wendat leaders was that the kinship group that had first made contact with Champlain (in regard to the 1609 raid) was fairly obscure. And so, if traditional custom were followed, a key component of the Wendat’s future would be in the hands of people with little experience in political leadership, and little prestige within the Confederacy.

Everyone recognized that this would pose certain challenges. On the one hand, the French might take advantage of the situation, and exploit the inexperience of their partners. On the other, managing the French alliance might turn out to be so important that it radically altered power relationships within the Confederacy overnight. That, in turn, might lead to conflict.

The result of the Council was a compromise, hammered out in the interests of stability. Management of the French alliance would be handled at the Confederate level. This meant, in practice, that the largest nation (named the Attignawantan) would play a dominant role. The nation that had first established a relationship with the French, the Arendarhonon, would retain special status as particular friends of the French.

The Council also decided to send a large delegation to meet Champlain when he returned to the St. Lawrence in the Summer of 1611. Fifty chiefs would participate, representing all of the constituent nations of the Confederacy. The goal was to put a formal stamp on the French alliance, binding the two parties together in a series of ceremonies.

But as these men moved down the Ottawa River toward the St. Lawrence, they encountered several parties of Innu, who carried troubling news. Savignon, the Wendat youth who’d joined Champlain in France, was dead. Champlain himself was looking to betray the alliance and throw in with the Iroquois. All that awaited the Wendat on the St. Lawrence was an enemy ambush.

Confusion reigned. What was going on?

It appears that the Innu had gotten word of the formalization of the Franco-Wendat alliance, and were doing their best to disrupt the affair. Although they were all a part of the same Laurentian coalition, the Innu feared a decline in their importance if French attention shifted westwards, away from their traditional base at Tadoussac. Open confrontation wasn’t an option. So instead, the Innu spread rumours that would hopefully discourage the Wendat from continuing their voyage.

But the Wendat party ignored the warnings, and continued on. In reality, Champlain was waiting for them at the rapids. He’d actually arrived a week later than he’d promised back in 1610, but the Wendat party turned out to be delayed even longer. (It was difficult to keep appointments in seventeenth-century Canada, especially ones made a year in advance.)

In mid-June, everyone met at the rapids and the coalition was renewed in a ritual ceremony. The Algonquins were excluded from the event, highlighting the importance of the Franco-Wendat relationship. Although the Algonquins of the Ottawa River were allies, and necessary middlemen in the fur trade, the Wendat chiefs were making a clear statement about who had the most power in this coalition.

With the formalities out of the way, all sides shared in mutual hospitality. Brûlé shared stories with Savignon, with both now wearing the garb of their respective hosts. Brûlé wore the same animal skins as the men he’d accompanied to the St. Lawrence, as Savignon demonstrated his newfound taste for European clothes.

But while Savignon was eager to return to his people (he had not enjoyed his time in Europe), Brûlé asked for permission to remain among the Wendat. Both Champlain and the chiefs readily agreed. The French were particularly eager for Brûlé to continue learning the Wendat language. True to their custom in dealing with the Algonquins, Wendat traders carried out business with the French in their own tongue. It’s a testament to the leverage they had within the coalition that the French largely complied with this practice. Being bilingual, Brûlé was a valuable resource, facilitating trade between Wendat sellers and French buyers on the St. Lawrence.

Brûlé was invaluable in another sense, too. Champlain was still struggling to sort out the inter-connected relationships among the various Algonquin nations and the Wendat Confederacy—not to mention the kinship groups that made up the confederacy. On top of this, Champlain had difficulty wrapping his head around the non-coercive nature of Indigenous political systems. By European standards, Champlain was an unparalleled expert on Indigenous politics. But that was an extremely low bar, and he continually made faulty assumptions about how power worked, especially when it came to the authority wielded by chiefs.

Champlain also assigned another young man, Nicolas de Vignau, to liaise with the Kichesipirini, perhaps the most important of the middlemen Algonquin groups in the Ottawa River valley. The traditional summer settlement of the Kichesipirini occupied a strategic point on the Ottawa River: Morrison Island, about 300 km upriver from the St. Lawrence, near the modern Ontario city of Pembroke. Fierce rapids both above and below the island made it difficult for convoys to pass through without enjoying the hospitality of the Kichesipirini. And that hospitality usually entailed the exchange of gifts. (Another option would be for visitors to trade with the Kichesipirini directly. That way, they could turn back home and avoid an even longer return trip to and from the St. Lawrence.)

This advantageous position in the main artery of trade made the Kichesipirini one of the more important Algonquin nations within the coalition. Their forceful chief, Tessouat, had made an impression on Champlain when the two had met at Tadoussac back in 1603. And the Frenchman saw the benefits of renewing their friendship now, eight years later.

Sending Vignau to live among the Kichesipirini was a sign of Tessouat’s special status within the coalition. It also may have reflected Champlain’s knowledge that the Algonquin chiefs had been perturbed by the exclusive nature of the Franco-Wendat alliance ceremony that summer. Though Champlain could see that the Wendat were the dominant Indigenous power in the region, he didn’t want to risk alienating the Algonquins, who had their own role to play.

But Champlain had greater ambitions for Vignau’s mission than simply placating an important ally. As noted above, he had pressed the Innu to guide him toward the rumoured great sea in the north. But each time, his allies found reasons to refuse or delay his request, and Champlain was beginning to doubt he’d ever get the Innu to take him all the way up the Saguenay. Brûlé’s winter among the Wendat had opened up an alternative: The translator reported that the Wendat/Algonquin trading network reached to the northern sea as well.

Tessouat’s people represented an important link for anyone embarking on this northern route. The Kichesipirini traded with the Nipissing—another Algonquin nation, one that occupied the western end of the Ottawa River route, north of the Wendat homeland along Georgian Bay. The Nipissing, in turn, made annual trips to the far north, where they traded with another Algonquin-speaking group, the Cree. Champlain hoped that Vignau might gather intelligence on this northern sea in the coming winter—perhaps even visit it himself.

Champlain suspected that the rumoured northern sea could be reached via the North Atlantic. In fact, he was correct in this respect. Had Martin Frobisher (discussed in our eighth instalment) continued his Arctic explorations just a little further west, he would have found a massive bay that cut almost 1,500 km south, toward the Wendat trading network. Champlain wanted Vignau to confirm the existence of this alternate route into the Canadian interior.

This possible northern route was seen as a boon to the fur trade: In general, the further north you went from the St. Lawrence, the higher the quality of the furs. But it’s also important to remember that Champlain hadn’t yet given up his dream of finding a way past the great rapids on the St. Lawrence. If he could find a navigable waterway to this northern sea, he might also unlock the fabled Oriental passage. That had the potential to revolutionize the colony at Quebec—turning it from just a profitable fur-trading depot into a new capital of global commerce.

Unbeknownst to Champlain, in 1611, just as he was issuing his final instructions to Vignau, a group of Europeans was already sitting on the coast of the great northern bay that occupied Champlain’s thoughts, waiting for the summer thaw to free their ship from the ice. Having led the first European expedition to sail these waters, their captain lent his name to this sea—which is now known to the world as Hudson Bay.