Nations of Canada

Champlain Goes to War

In the thirteenth instalment of our series on the history of Canada, Greg Koabel describes the crucial battlefield alliance that French explorers forged with Indigenous allies in 1609.

What follows is the thirteenth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialized Quillette project adapted from Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name.

In the summer of 1607, Pierre Dugua de Mons became the third Frenchman in a period of seven years to prematurely surrender his state-granted monopoly on the fur trade in New France.

Unlike his predecessors, however, de Mons wasn’t willing to give up on the dream. Even without a monopoly, he was determined to keep his company together. This required significant sacrifices on his part—including the use of his personal funds to buy out most of his investors (who, by this point, saw the project as a dead letter).

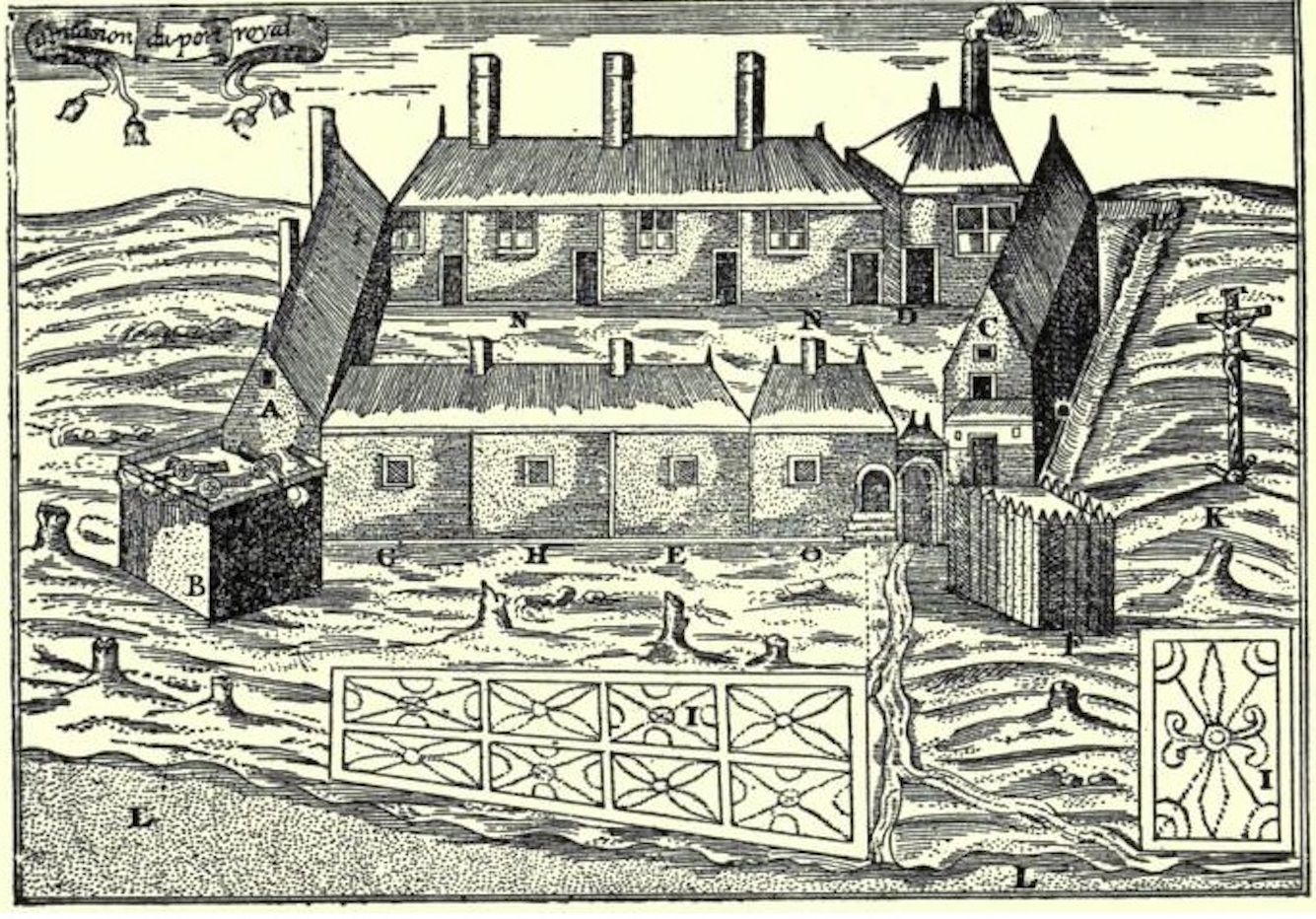

It also meant starting from scratch. Without backing from investors or King Henri IV, de Mons didn’t have the resources necessary to maintain a colony on the other side of the Atlantic. As discussed in the previous instalment of this series, the settlers at Port Royal, having suffered through three long, hard winters, had been forced to pack up their things and return home to France.

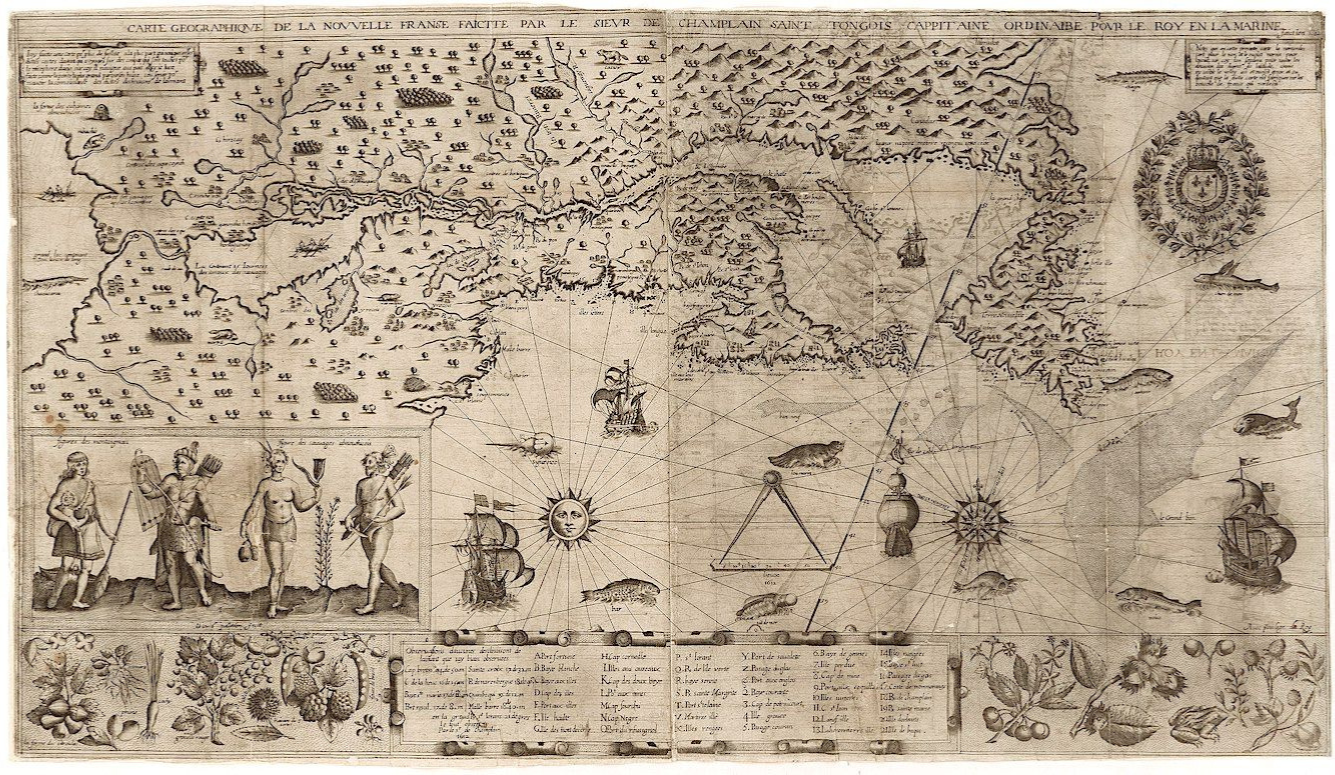

Several of de Mons’ colleagues similarly remained committed to the project. Samuel de Champlain, the royal cartographer, was convinced that a passage to the Orient (as it was then known) was still possible—either by bypassing the great rapids at modern-day Montreal, or finding a waterway that linked to the St. Lawrence upriver from that obstacle. Recent French exploratory voyages down the Atlantic seaboard hadn’t made much progress, but Champlain still had leads to follow up among the Indigenous friends he’d made during his initial voyage, in 1603. Until he’d thoroughly charted the St. Lawrence region (ideally with the help of expert Indigenous guides), he wasn’t willing to give up hope.

Meanwhile, Jean de Poutrincourt, the French aristocrat who’d claimed ownership of the (now abandoned) Port Royal colony whose rise and fall we documented last time around, immediately started drawing up his own plans to return to what the French called Acadie (Acadia).

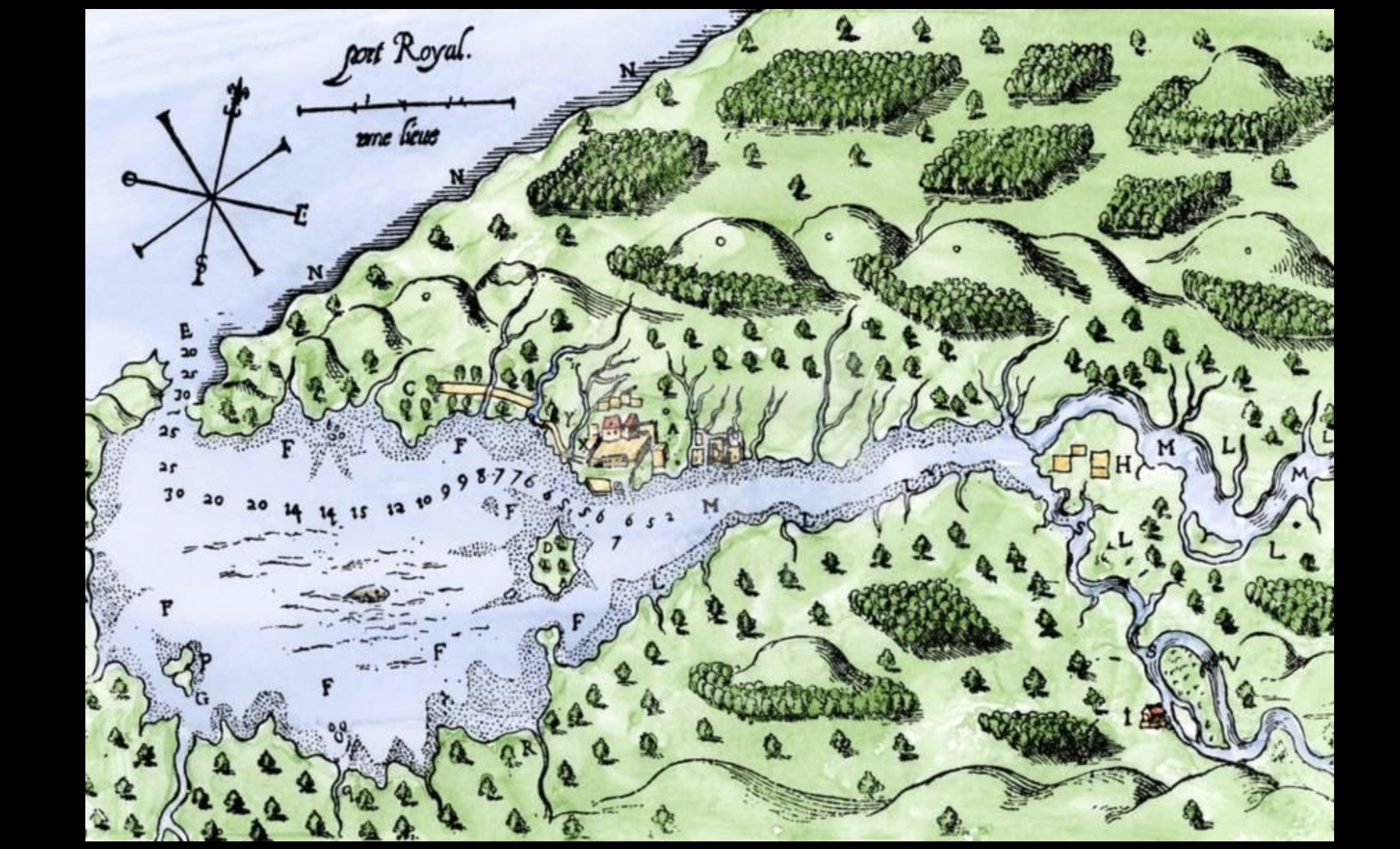

His control of the area’s excellent natural harbour, situated in an area of brisk Indigenous commerce, was officially recognized by France. Port Royal also was blessed with friendly Mi’kmaq neighbours, especially those led by the venerable chief Membertou. All the elements of a profitable colony were there. Poutrincourt just needed some start-up capital to make it happen.

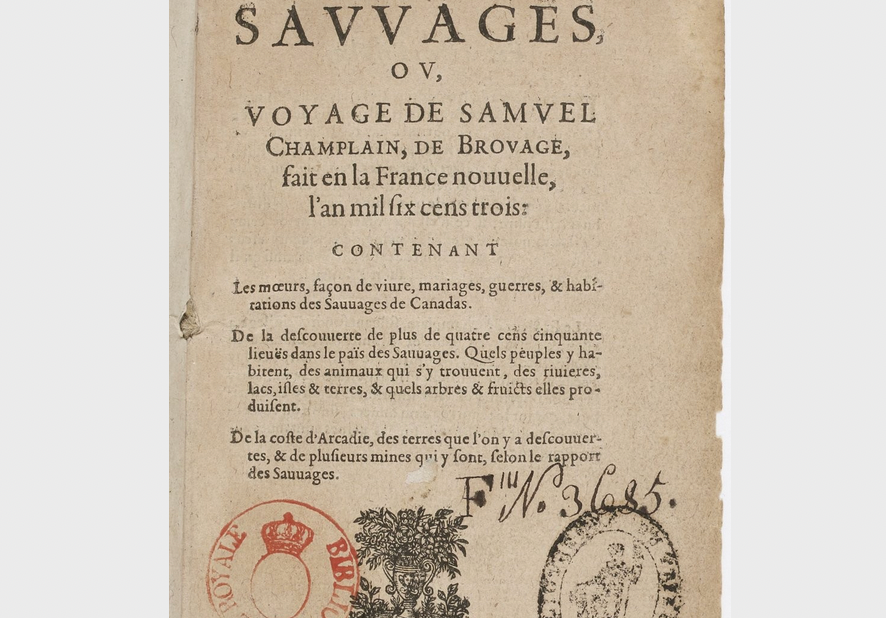

The once and future colonists had also captured the popular imagination of the home audience. Before leaving for Acadia, Champlain had published Des Sauvages, an account of his trip down the St. Lawrence in 1603. And Marc Lescarbot, the lawyer and poet who’d joined his friend Poutrincourt at Port Royal, wrote an epic poem celebrating the adventures of the colonists (which he followed up with a history of the French settlements in America).

But a basic practical problem remained: French settlements couldn’t protect inhabitants from the brutal Canadian winters. Rather than progressing towards self-sufficiency, colonies had to be effectively rebuilt from scratch every spring. Ships set out from France with new men to replace those who’d died, or were too weak to continue their work.

And what were the French getting for this sacrifice? Commercial competition for fur was as fierce as ever: As French settlers focused on survival, independent seasonal interlopers continued to trade with Indigenous suppliers at the main trading hub of Tadoussac, in violation of whatever monopoly the French claimed. The fledgling colonies provided no security for French traders. In 1606, for instance, a single Dutch raid on Tadoussac cost de Mons’ operation half of its inventoried furs.

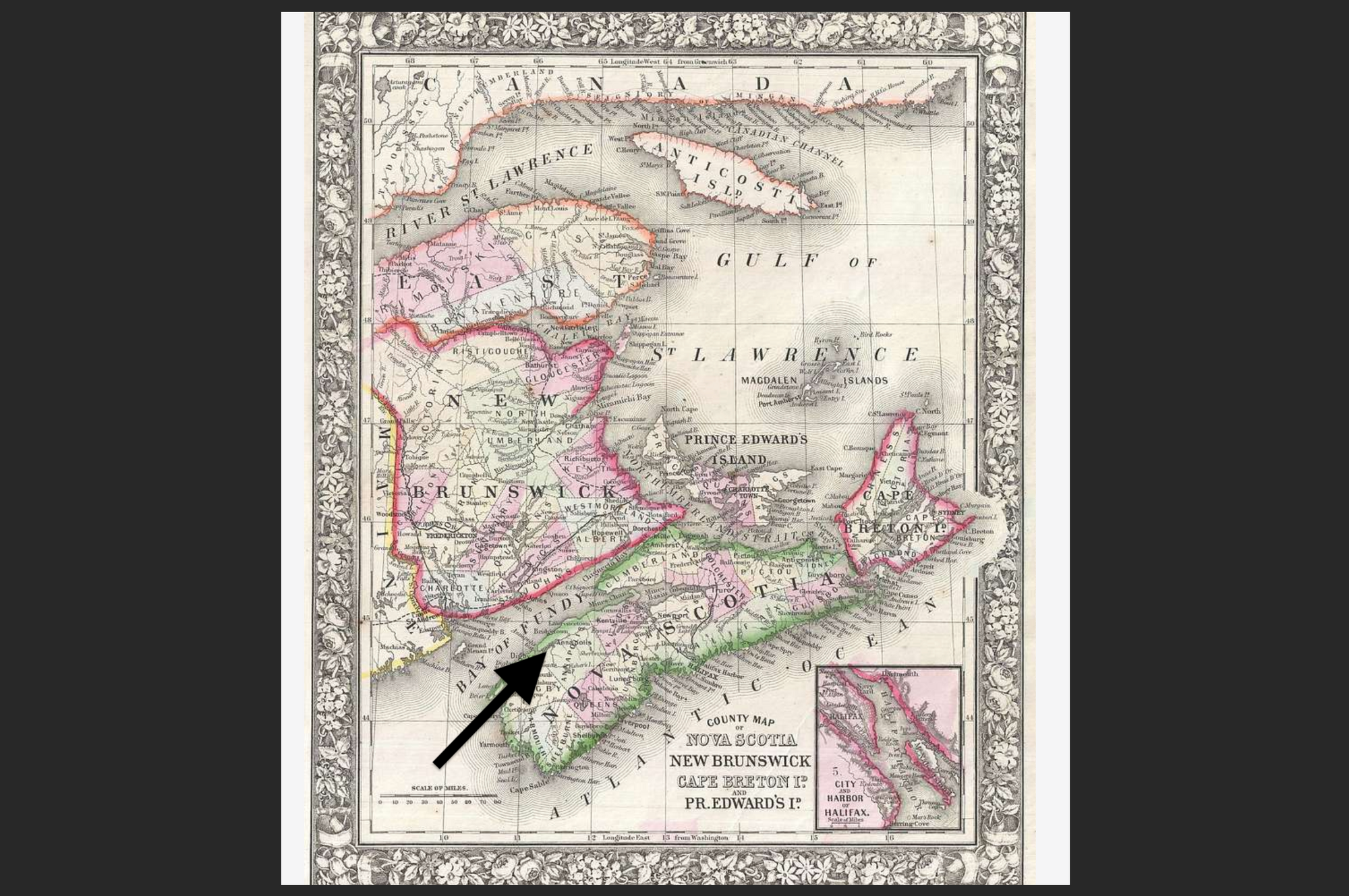

To reignite King Henri IV’s flagging interest in Acadia, de Mons emphasized the geopolitical perils of allowing other European powers a foothold. In particular, he focused on the English. In 1604, James I had secured a peace with Spain, allowing the English to shift their naval resources to inter-continental colonization. And the possibility of English settlement already had driven de Mons and Poutrincourt to (unsuccessfully) seek to exert French influence as far south as Cape Cod.

At the same time that Port Royal colonists were packing up for home, in fact, a group of English settlers were landing at Jamestown—the site of what would become the first permanent English plantation in America. Even more troubling for the French was a second group of English settlers, who built a base at the mouth of the Kennebec River, just 200 kilometers south of the original Acadian settlement on Saint Croix Island.

Led by two West Country men, Raleigh Gilbert and George Popham, these English visitors stayed throughout the winter. For the past three winters, the French had been the only Europeans in the region. But now, they’d surrendered that advantage, and the potential effect on French fur traders could be devastating.

As it happened, the English threat was not as immediate as the lobbyists feared. Gilbert and Popham found winter on the Kennebec to be as harsh as the French had found it in Acadia, and so they abandoned their settlement in the spring. While the Virginia Company continued its program of plantation and permanent settlement, the West Country investors who controlled the northern part of the American coast now focused on seasonal fishing and fur trading rather than colonization. At the time, however, no one in France knew that this is how English fortunes would eventually unfold.

The appeal to French geopolitical interests was mixed with an appeal to glory. For the first time, Champlain and his colleagues began emphasizing Canada’s potential as a missionary project. Bringing the word of God to the people of the New World would elevate the prestige of both France, and King Henri IV, it was claimed. After all, Spain had built its impressive global empire on a similarly high-minded conceit.

Membertou, the Mi’kmaq chief whose people neighboured Port Royal, had seemed enthusiastic about learning European religious practices. In this regard, however, he was probably just looking to formalize his economic links to the French by participating in their rituals. This was a common practice in the world of Indigenous diplomacy, and typically didn’t indicate sincere religious conversion. Nevertheless, such displays were presented to Europeans as evidence that the native people of the Americas were drawn to the Christian faith.

To this point, de Mons and other colonial leaders had been hesitant to bring religion into the picture. Not least because de Mons himself was a Huguenot—i.e., a Protestant living in largely Catholic France—and any grand missionary project would have to be Catholic. (As discussed in previous instalments, Huguenots comprised a minority in France, but were dispropotionately represented among the coastal merchants involved in the fur trade.) If Catholic missionaries became a major presence in Acadia, they could easily plant the seeds of resentment and infighting.

But de Mons, Champlain, and their partners had little choice: If they wanted to restore their all-important trade monopoly in the region, they would have to make an appeal to Catholic France. This pitch was especially attractive to King Henri IV, whose conversion to Catholicism (discussed in our tenth instalment) was widely seen as a political expediency. What better way to assure the loyalty of his Catholic subjects than by winning a great victory for their Church?

For now, de Mons tried to maintain a tricky balance. He held up the promise of company-supported religious conversions, but avoided making a formal partnership with any Catholic religious order. The result was a mixed success: In 1608, the King announced that he had reconsidered his position on the trade monopoly. Rather than dissolving it outright, he gave de Mons a twelve-month reprieve. The monopoly would hold for just one more summer. If his company couldn’t make it work in that time, then the project would be permanently abandoned.

Recognizing that enforcement was key, de Mons built up a permanent legal team in Rouen, the town in Normandy where the majority of legal cases involving the fur trade were likely to play out. He realized that one mistake he’d made in 1604 had been to travel to Acadia himself. The success of the venture depended on events on both sides of the Atlantic. De Mons had to stay in France, and fight for his company’s political and legal interests.

De Mons also spent the winter of 1607-08 travelling to major fur-trading French ports, drumming up new investment. By calling in every possible favour, and putting his own name and savings on the line, de Mons was able to secure enough funding for a new expedition in the spring of 1608—but only just. This time, the colonists would be operating on a shoe-string budget.

It didn’t help that de Mons and Champlain still disagreed on where to set up their colony. De Mons had been encouraged by the successful final winter at Port Royal. While a lack of support in France had forced the abandonment of the colony, the settlers themselves had proven the physical viability of the location. The local Mi’kmaq were friendly, and Champlain had produced quality maps of the region through exploratory work. If Membertou had kept his promise to safeguard the Europeans’ abandoned home, Port Royal was still sitting there waiting to be re-occupied. Why not pick up where they’d left off?

Champlain, however, once again argued for a location on the St. Lawrence River. The Port Royal colony was viable, yes. In fact, Champlain was proud of the work he’d done in Acadia (as attested to by the surviving maps and drawings he made of the Port Royal and Saint Croix settlements). But Acadia was simply too far from the main trading centre at Tadoussac to be of much use in enforcing any monopoly. The French had to be closer to the action.

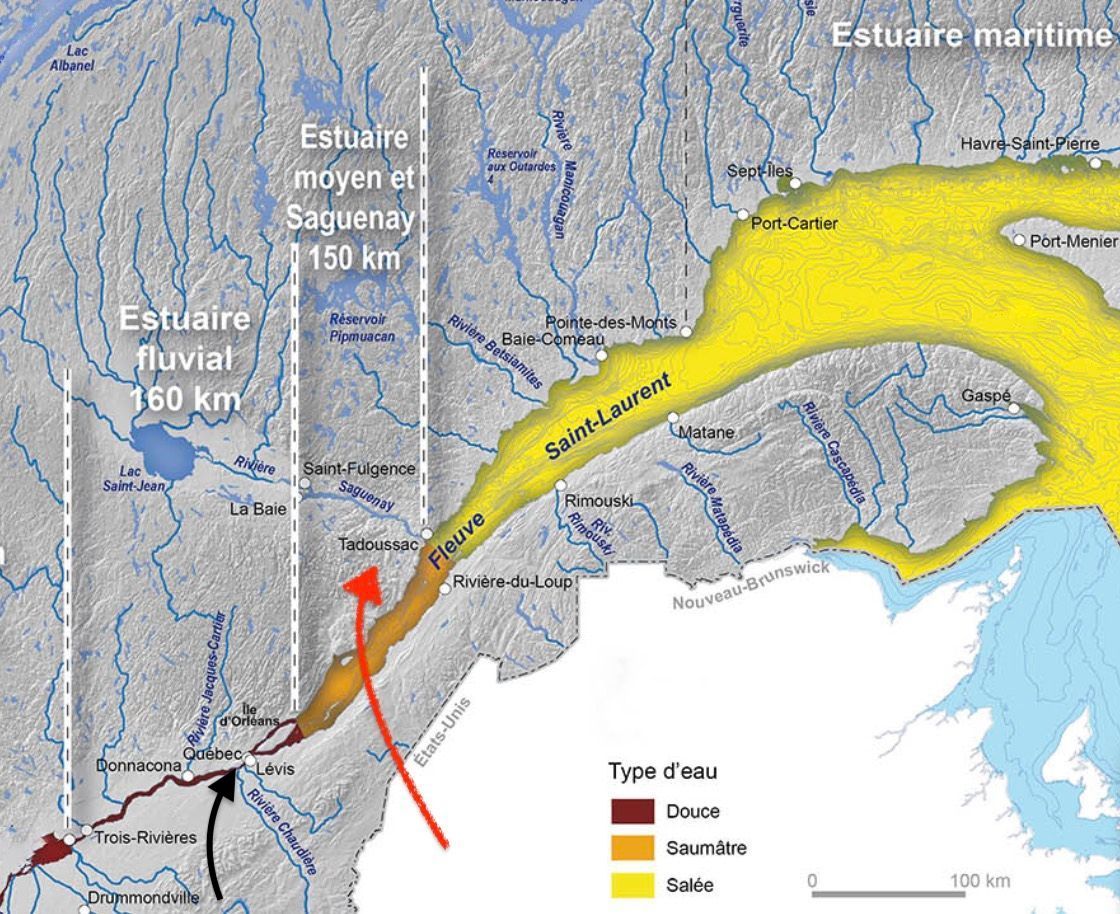

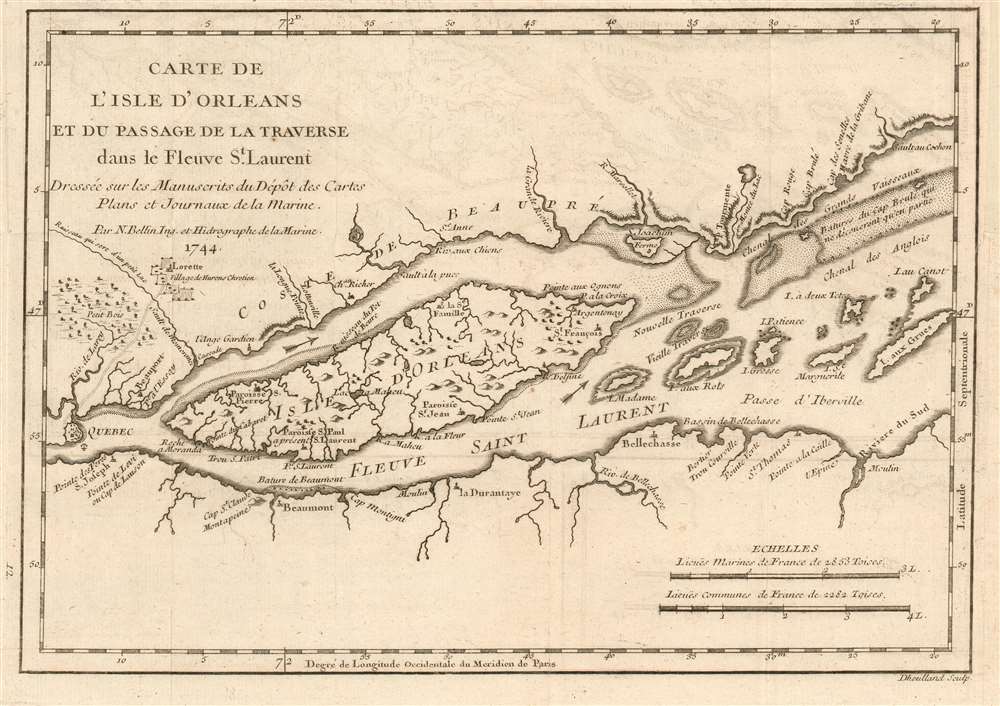

For Champlain, there was only one location that made sense—the place where the St. Lawrence River narrowed. This was the site of the (now abandoned) Stadaconan village that Jacques Cartier had visited back in the 1530s, near modern Quebec City. It was close enough to Tadoussac to allow the French to keep an eye on the European fur trade, while commanding a strategic choke point on the St. Lawrence.

Ever the cartographer, Champlain was also still thinking about a passage to the Orient. He’d spent much of the period between 1604 to 1607 searching the Atlantic coast for a waterway that might lead west and north, from the coast of modern United States back up to a point on the St. Lawrence upriver from the great rapids at Hochelaga (modern Montreal), which were impassable to European ships. He now wanted to take a closer look at those rapids. A base on the St. Lawrence would give him an opportunity to search for a way around that white-water obstacle.

In the end, Champlain won this argument, an indicator of his heightened influence. During the voyages of 1603 and 1604-1607, Champlain had been an ambiguous figure—a well-connected consultant who lay outside the formal command structure of the corporate body he served. But now, in 1608, Champlain was put in charge of the whole expedition—his first independent colonial command. This gave him even greater freedom to pursue his goals, even if managing the men under his authority would pose new challenges.

Champlain’s first challenge greeted him as soon as he arrived at Tadoussac on June 3, 1608. Several European ships, he observed, were already anchored. These traders had gotten an early start, leaving Europe, in some cases, before they’d even had a chance to learn of the newly announced French trade monopoly. One Basque captain named Darache, hailing from the Spanish side of the Pyrenees Mountains, seemed to be particularly well-established at Tadoussac.

At this point, it should be acknowledged that the legal framework governing European claims to the Americas were a fuzzy area within the already fuzzy world of (proto) international law. The legal claims made by various European powers were by no means absolute or universally respected. But certain widely agreed-to principles of international law (or, as we might more properly call it, Europe’s understanding of international law, since Indigenous groups were never consulted) did carry influence. In fact, one of the reasons why the English had been so eager to establish a winter colony in the Arctic during Martin Frobisher’s voyages of the 1570s (as described in our eighth instalment) was that year-round settlement was considered to be an important marker of colonial ownership.

And so, while independent-minded traders such as Darache might have had their own views about what Champlain could do with his claimed legal rights, he would also have known that violating a monopoly granted by the King of France might cause a diplomatic incident for his own sovereign (an infraction for which he might be punished severely).

On the other hand, the Basques had long asserted their own rights. For decades, they’d played a trailblazing role in establishing the fur trade, albeit without the official sanction of monarchs or monopolies. On both sides of the Pyrenees, Basque traders made the argument that since they’d pioneered this trade in the first instance, they were exempt from subsequent attempts to restrict, or regulate the industry on behalf of Henri IV or anyone else.

The legal status of these claims was contested back in Europe, but it was a passably grey area that allowed Basque traders to act more confidently than, say, the independent French traders who plied the same waters.

Realizing that the fate of the whole enterprise might hang on this precedent, Champlain opted for a show of strength. François Gravé (known as Pont-Gravé in historical texts), the hard-bitten sailor who’d been serving as the French naval enforcer on these missions since 1603, demanded that Darache and the other Basque traders submit to search and seizure. Darache responded by opening fire. Pont-Gravé was wounded in this brief skirmish, and the French quickly surrendered.

But, although nominally victorious, Darache realized that declaring a personal war against the King of France was probably a bad idea. He released his French captives, and agreed to settle their dispute back in French courts. In the meantime, though, he’d take his fur haul back to the European market.

This outcome was a blow to Champlain’s mission: Before he’d even landed, serious doubts were raised about whether his monopoly could be enforced.

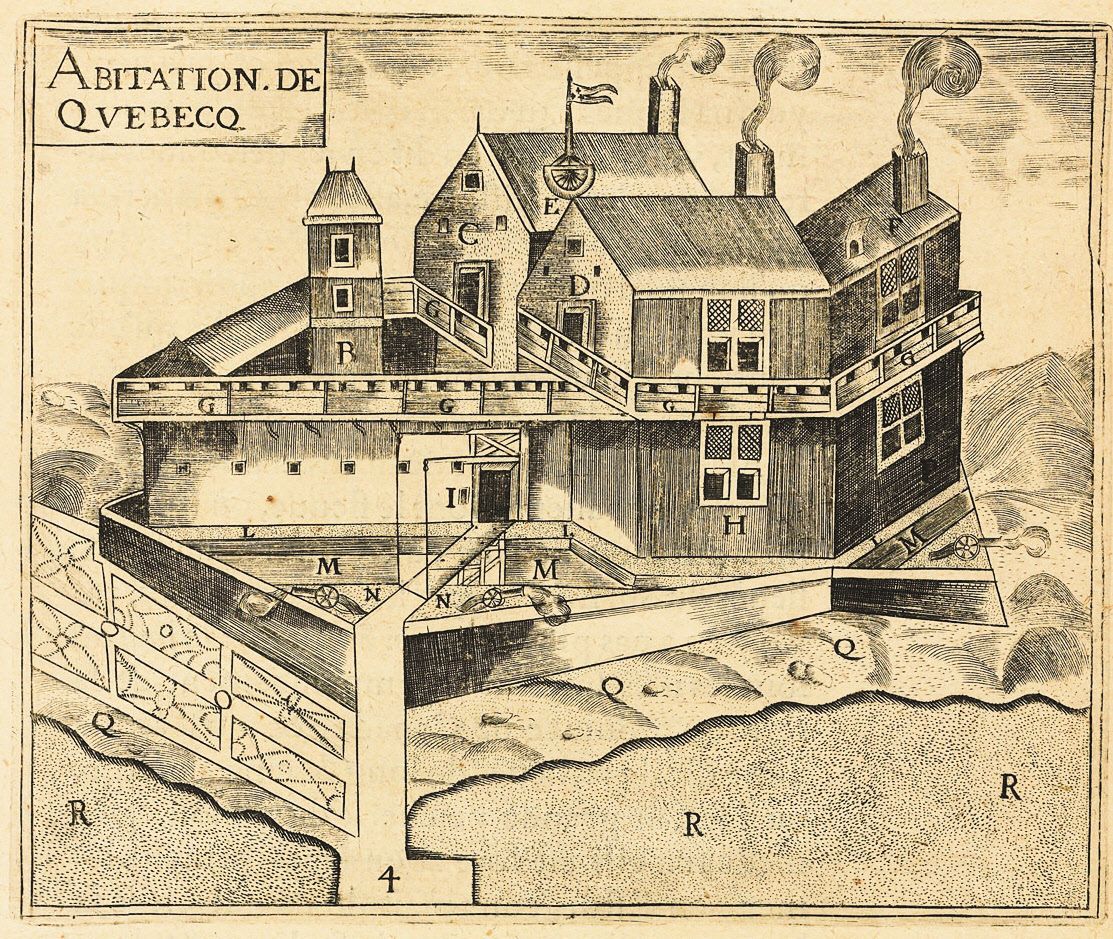

A month after the unpleasantness at Tadoussac, the French expedition began work on the new colony, near the site of the old village of Stadacona. Champlain called the settlement “Quebec,” after the Algonquin word for “where the river narrows,” kebec.

The settlers built a wooden structure (which Champlain called the “Habitation”) on the north shore, just upstream from the river island now known as Île d'Orléans. The location boasted a flat, riverside landing area ideal for trade, overlooked by high cliffs, from which a fort could dominate the river.

Champlain’s strategic instincts on this score were excellent. And while he couldn’t know it at the time, this would be the very site where the French and British would fight a decisive battle for control of North America 151 years later—now known to (Anglophone) Canadian schoolchildren as the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

Among the settlers who came ashore was Jean Duval, a veteran of the Acadia mission. During the previous voyage, Duval had been the only survivor of a five-man French team that had sparked a battle with local Indigenous forces on a Massachusetts beach (an event described in the last instalment).

Two years later, Duval was once again at the centre of a life-and-death drama, having apparently come to some kind of unwholesome arrangement with Darache back at Tadoussac. While on the surface, the Basque trader had appeared willing to resolve his dispute with the French through legal means, it later emerged that he’d encouraged Duval to take a more under-handed approach. Likely in exchange for cash, or a cut of the fur profits, Duval was enlisted in a plan to overthrow Champlain, then pass control of the fledgling colony to the Basques or the Spanish (who would presumably destroy it).

It wouldn’t be hard to pull off a mutiny. Pont-Gravé and the three ocean-going vessels that constituted his fleet had stayed at Tadoussac to trade and enforce the monopoly. Meanwhile at Quebec, Champlain and a small group of about 30 men constructed the Habitation. If they moved quickly, Duval and his handful of co-conspirators reasoned, they could seize or kill Champlain, and take over the settlement.

Luckily for Champlain (and the future of French Canada), Duval recruited one too many allies. A pilot named Guillaume Le Testu had second thoughts, and revealed the whole plot to Quebec’s commander. Champlain moved quickly and held an impromptu trial. Four ringleaders were identified. Unsure of his precise legal authority, Champlain sent three of them back to France to face the King’s justice. But an example had to be made of Duval, the chief plotter, who was hanged, then beheaded. His head was then displayed prominently on a pike in the centre of the settlement.

After that inauspicious beginning, Quebec faced an even more daunting challenge—winter.

At first, Champlain could take some comfort in having been proven right in his old argument with de Mons: These upstream areas on the St. Lawrence did indeed have milder winter climates than at Tadoussac or Port Royal. Indeed, the winter of 1608-09 was particularly mild.

However, this apparent stroke of good luck presented other problems. Champlain had banked on trading with Quebec’s neighbours, the Innu, to get the fresh game that he believed was vital to staving off scurvy. But the unusually mild winter disrupted the normal operations of the Innu economy: An abnormally wet fall had raised water levels, making it difficult for hunters to access beaver lodges (whose contents provided the Innu with an important source of stockpiled winter food).

Then came the warm, dry winter months. In a normal year, large snowbanks rendered moose and deer less mobile, and easier to hunt. In the winter of 1608-09, on the other hand, there was nothing to prevent the animals from scattering freely when hunters appeared. Even the eels, which the Innu collected in the late winter and early spring, seemed to have become scarce, likely thanks to unusual weather patterns.

By February 1609, the 28 settlers in Quebec were starting to get nervous. They had ample supplies of grain and beans, but the tell-tale signs of scurvy were beginning to appear. And the Innu who visited Quebec were often in as much need as the French. Champlain reported large groups of them appearing on the opposite bank of the St. Lawrence, desperately trying to cross in search of food and shelter. Some managed to climb onto ice floes in the middle of the river, and cried out for help. By the time salvation arrived in April, in the form of large schools of fish, only eight of the original 28 settlers were still alive.

In June, a supply ship dispatched by de Mons sailed into view. It carried 16 more settlers, but also grim news about the monopoly. Despite his best efforts, de Mons had not been able to win a further extension from the King. The monopoly’s one-year term had expired. Champlain was ordered to return home at the end of the summer, as there was no more money left to maintain his Habitation at Quebec.

But Champlain had a plan to save the whole enterprise, one that he’d been thinking about for several months. As he saw it, the Company had to look beyond regulating the existing fur trade being run out of Tadoussac. It had to massively expand that trade. And Champlain thought he knew how.

Champlain’s idea traced back to his first trip to Canada in 1603, when he’d fortuitously stumbled on a large assembly of victorious Indigenous warriors at Tadoussac. This large coalition of Innu and other Algonquin-speaking peoples from all over eastern Canada had been celebrating one of their rare victories over the Iroquois Confederacy to the southwest. Champlain made several friendships that day, some of which had been renewed since his return to the St. Lawrence.

Many of those chiefs whom Champlain had met normally resided deep in the interior of the continent, far from the fur-trapping territory that supplied the Innu middlemen who kept fur pelts moving down the Saguenay River to European buyers at Tadoussac. If the geographic intelligence Champlain had gathered was correct, these inland groups could procure a massive volume of fur from (currently untapped) lands beyond the great rapids of the upper St. Lawrence.

Furthermore, Champlain’s discussions with these chiefs also revealed the key to unlocking that commercial potential. Again and again, Algonquin leaders urged Champlain to ally with them against their traditional enemy, the Iroquois. It’s possible that the Innu (a group that is distinct from Algonquin peoples, but which speaks an Algonquian language) also pressed Champlain for an alliance during the winter of 1608-09, as Iroquois raids likely contributed to the misery they’d suffered during this period.

Desperate for a way to save the colonial project, Champlain came up with an idea that would appeal to both French and Algonquin supporters alike: Before heading back to France at the end of the summer, he would join his Indigenous allies in a daring raid into Iroquois territory. In exchange, Algonquin guides would show him the interior lands that no European had ever seen, beyond the great rapids at Montreal. By linking this new network to the existing Atlantic fur trade, Champlain believed he could unlock unimaginable wealth, all of it to be funnelled through a newly formed permanent colony at Quebec.

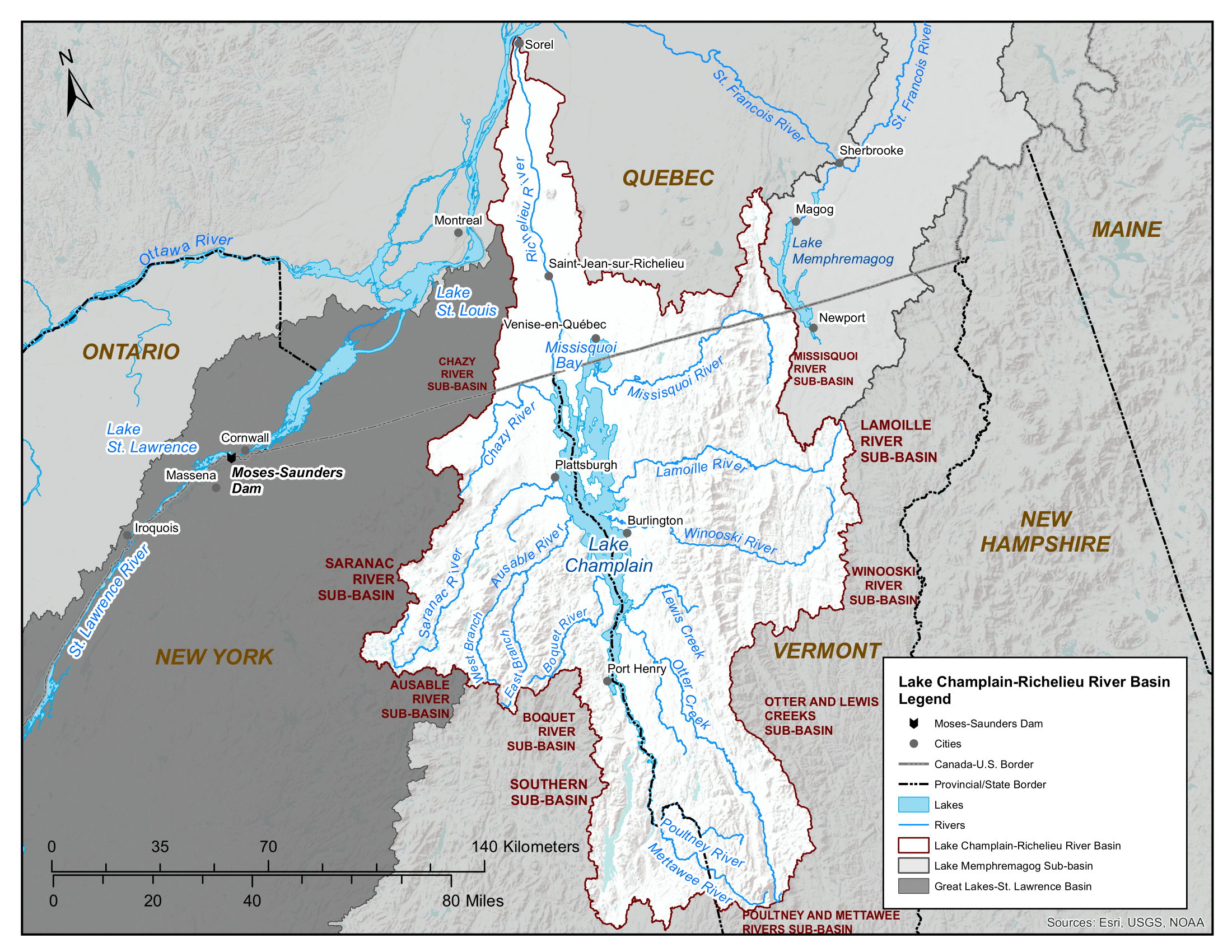

By the time spring came, word of Champlain’s willingness to join in a military alliance had spread. Crucially, some of the Indigenous groups that heard the news lived along the Ottawa River, which met the St. Lawrence at Montreal, west of the rapids. Like the St. Lawrence, that river, too, would soon become a crucial part of Canada’s story. Through a network of waterways and portages, the Ottawa River valley linked the St. Lawrence to Georgian Bay, more than 600 kilometers to the west. From there, the great open waters of Lake Huron connected the route to the Wendat Confederacy, which was based on the bay’s southwestern coast, in modern Ontario.

The Ottawa route predated European commerce by many centuries. The Iroquoian-speaking Wendat who regularly plied the river were accomplished traders, and did business with the various Algonquin-speaking nations that lay downstream. Fittingly, the word “Ottawa”—which would also become the name of Canada’s capital city more than two centuries later—was adapted from an Algonquin-word, adawe, meaning “to trade.”

These were the people whom Champlain was interested in partnering with, even if all he knew about them came from second-hand accounts supplied by other Indigenous groups. And as it turned out, the feeling was mutual. European goods, originally procured in exchange for furs, had been making their way along the Ottawa route since at least the 1580s. The Algonquin middlemen were more than willing to increase the volume of trade, as were the Wendat at the other end. Perhaps more importantly, all of these parties were interested in striking a blow against the Iroquois to the south—especially if that meant shifting the theatre of war onto Iroquois turf to the south, rather than having to fight them off north of the St. Lawrence.

The linchpin of the grand coalition that assembled in the spring of 1609 was Iroquet, a war-chief of the Onontchataronon, a group of Algonquin-speakers based on the Ottawa River, just upriver from the St. Lawrence. He’d met Champlain at Tadoussac back in 1603, and now had become intrigued by rumors that he was back in the region, looking to strike the military alliance that Indigenous leaders had suggested to him during that early meeting.

His group of Algonquin speakers were seasonal migrants. Their area around the Ottawa River supplied him with a summer base for the purposes of fishing and (subsequently) trade. But his kinship network also often wintered on the other, northern end of the great Ottawa route—among the Wendat. This latter practice was in keeping with Indigenous customs of trade and hospitality: Hosting visitors (especially over the winter) was an excellent way to build strong relationships.

Before setting out for his return trip to the St. Lawrence in 1609, Iroquet convinced some of his Wendat friends to join him, to see what kind of friendship these Europeans offered. As they travelled down the Ottawa, this group attracted more men from the Algonquin-speaking communities they passed, with their numbers swelling to over 300 by the time they were done.

Some were drawn by the promise of a great raid on the Iroquois. Most though, brought canoes full of pelts for trade. Carrying fur into the St. Lawrence was usually dangerous work. But if it was true that the French now had a permanent base at Quebec, the trip would be safer (and more convenient) than journeying all the way to Tadoussac. With a great war party in the offing, the path was assumed to be clear of Iroquois raiders.

That was the hope, anyway. In fact, none of these Indigenous men really could be sure what they’d find on the St. Lawrence. And, in fact, as they got closer, the sense of uncertainty grew. The convoy started hearing new rumours—that the French had changed their mind, or that they’d abandoned their settlement altogether. This was most likely deliberate misinformation being spread by the Innu, who were now being put in an awkward position.

On the one hand, the Innu had much to gain from a military alliance between the French and the Algonquin nations that lay up the Ottawa River, as the Iroquois posed as much of a threat to them as anyone else. On the other hand, contact between the French and the peoples of the Ottawa River route was bad news for the Innu from a commercial perspective. In recent years, the Innu had adapted their society to their role as middlemen of the Tadoussac fur trade. If the Wendat and their Algonquin intermediaries started doing business directly with the French on the St. Lawrence, the relevance of Tadoussac would decline, along with Innu fortunes.

There’s an interesting kind of symmetry to this historical period: Just as the French were worried about maintaining a monopoly in regard to European competitors, so, too, were the Innu worried about their own monopoly in regard to fellow Indigenous groups.

Faced with this dilemma, some Innu adopted a tactic that would become a familiar part of French-Indigenous relations (and which we’ve discussed before, in regard to the scary stories about aggressive Indigenous groups that the Innu had spun to Champlain as they’d sailed together up the Saguenay years before): the dissemination of false rumour. But Iroquet and his fellow travellers kept their nerve, being determined to appraise this new military/commercial opportunity for themselves.

In mid-June, Iroquet’s party arrived at the St. Lawrence, whereupon he and his followers let the current take their canoes downriver toward Quebec. About 40 kilometers from the settlement, they were met a small group of around twenty Frenchmen, Champlain included, and a handful of Innu. Iroquet and Champlain renewed their friendship, and the Algonquin chief asked for a demonstration of European firearms, seeking an early indication of what French military support might look like.

Once Iroquet’s curiosity had been sated, Champlain escorted the convoy back to Quebec, where their cargo of furs could be sold. This was, of course, a key component of Champlain’s scheme. And he was determined to relay news of this successful commercial transaction to authorities back home. He was especially gratified by the presence of the Wendat who’d accompanied Iroquet. The powerful confederacy at the far end of the Ottawa trade route held the key to the inland fur network.

But in order to formalize the arrangement, the new trading partners had to join together in war, too. And after just over a week in Quebec, the convoy was ready to head back up-river. In all, this attack force consisted of about 400 Indigenous warriors—a mixed group of Wendat, Algonquins from the Ottawa River, and Innu—as well as 12 Frenchmen, led by Champlain himself. The indigenous warriors paddled against the current in over 100 canoes, while Champlain and his men followed in a light sailboat (known as a shallop).

About 170 kilometers upriver from Quebec, at the site of the modern city of Sorel-Tracy, they stopped. Along the south bank, a northbound river emptied into the St. Lawrence. Champlain’s comrades informed him that it led to the homeland of the Iroquois. Fittingly enough, this river became known on French maps as the Iroquois River, though it would later become known as the Richelieu.

Here, there was some confusion. It turned out that most of the men on the voyage were not warriors at all, but traders, who, having completed their mission at Quebec, were now intent on continuing up the St. Lawrence, toward home. According to Champlain, however, at least some of these men had indeed intended to join the war party originally, but were now backing out.

In the end, only about 60 were willing to press on. But Iroquet assured Champlain that this was enough to execute a successful raid.

More troubling to the Frenchmen was the fact that their shallop would not be able to make the trip south, as the party would be running rapids and cutting across the land, work well-suited to birch-bark canoes but not European boats. Frustrated, but determined to continue on, Champlain ordered nine of his men to take the boat back to Quebec, while he and two others eased themselves into canoes. The unfamiliar conveyance was particularly unsettling for Champlain, as he did not know how to swim.

For the next six days, the war party made steady progress south, along more than 100 kilometers of riverways and overland portages. On July 14, Champlain observed that the riverway opened up into a long, thin north-south lake, a body of water that now bears his name: Lake Champlain.

Here, Iroquet and the other leaders ordered a halt. They were leaving no man’s land and entering the territory of the Mohawk, the easternmost, and fiercest of the Iroquois nations. The party camped for two weeks, to wait for the full moon to pass, as there was (relative) safety in darkness. From now on, they would move only by night, and stay hidden during the day. Foregoing conspicuous fires, they switched to a diet of cornmeal and cold porridge.

Champlain made a careful study of the warriors’ preparations. Iroquet was clearly a respected chief. But as far as Champlain could tell, there was no trace of the hierarchy that characterized European military affairs. Tactics were determined by debate and consensus, with warriors sketching out battle plans in the sand with sticks. These deliberations were complicated by the fact that this small party of Indigenous warriors contained four distinct cultures—Iroquet’s men, their Innu and Wendat allies, and the three Frenchmen.

Everyone agreed that Champlain and his two colleagues would be the key to the coming battle. As far as anyone knew, the Iroquois had never faced muskets. It was hoped that the shock of the weapon would terrify and confuse them.

For Champlain, the actions of his Indigenous allies would be just as important, although he was already thinking of the battle’s aftermath. If his gamble was going to pay off, he needed this small force of warriors to spread the tale of French military prowess to family and friends up the Ottawa.

By July 29, they’d travelled the length of Lake Champlain, having reached what came to be called Ticonderoga—adapted from the Iroquois word tekontaró:ken, meaning “junction of two waterways.” Champlain immediately recognized it as a strategic choke point that divided Lake Champlain from the waterways that continued to stretch southwards (an intuition that would be proven correct during the eighteenth century, when a fort built on this location would play a key role in multiple colonial conflicts, as well as during the Revolutionary War).

That night, they spotted the enemy—a Mohawk raiding party heading north. In fact, they both spotted each other roughly at the same time. Iroquet and the others rushed to confront the enemy on water. The Mohawk responded cautiously, aware that the Algonquins enjoyed a naval advantage: Their birch-bark canoes were far more manoeuvrable than the heavy elm canoes favoured by the Mohawk.

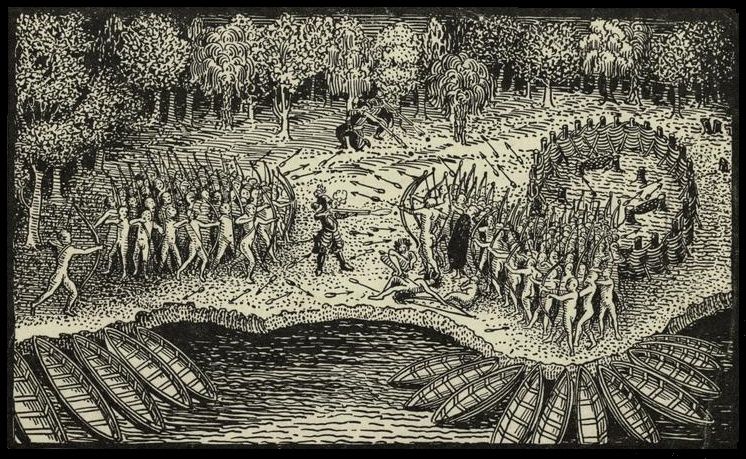

The Mohawk retreated to shore, where they hastily constructed a makeshift barricade. All night, the two sides taunted one another, and agreed to do battle on land when the sun came up. After the stealth they’d exercised over the previous two weeks, Champlain found the candid nature of these discussions bemusing. But, he also found parallels in his own European experience, later reporting that “an abundance of such talk” often is exchanged between armies during “the siege of a town” (an insight that will have some modern readers remembering a famous Monty Python movie scene).

As the sun came up, Champlain, Iroquet, and the others paddled to a hidden landing spot, and approached the fortified Mohawk camp, whereupon the Mohawk warriors came out in formation to meet them, appearing confident. In the light of day, it was clear that they outnumbered the invaders by a ratio of about five to one.

Few Europeans had any knowledge of Indigenous warfare in this region. And their tactics were about to undergo a revolution, in no small part thanks to the events that would transpire that day. So Champlain’s account of the battle offers a rare insight into the kind of Indigenous fighting style that was likely common during this period.

The Mohawk advanced in tight formation. Most of the warriors carried wooden shields and some wore wooden armour. Likely, this offered sufficient protection against arrowheads fashioned from stone. But once the two sides closed for hand-to-hand combat, the real fighting would begin.

This battle, however, had a different script. At a predetermined moment, while the two forces were still at a distance, the Algonquin and Wendat warriors parted in the middle, allowing Champlain to stride forward with his musket. He had stuffed four bullets down its barrel. This was not recommended usage, but Champlain was looking to deliver what we now might call “shock and awe.” Earlier, Iroquet had advised him on how to pick out a Mohawk war chief by his plumage. Champlain could see three men so adorned among the oncoming mass of bodies, situated conveniently close together.

For a moment, the Mohawk line paused, unsure of what they were observing. Then Champlain fired, killing two of the chiefs and another warrior instantly. The other two Frenchman, who’d taken up positions amid the trees on either side, also fired their guns, killing the third chief.

The Mohawk line panicked, much as European armies were prone to do when their leaders were slain, and ran. Champlain’s allies flooded past him in pursuit. In all, more than 50 Mohawk were killed, and a dozen were taken prisoner at virtually no cost to the attackers. The day had been a success beyond Champlain’s wildest dreams. His allies celebrated him as an incredibly powerful warrior.

Champlain had hoped that the spoils of war might include a bit of exploration further down the waterways extending south from Lake Champlain. But Iroquet explained that this was impossible. They were in enemy territory, and the alarm was already spreading. Pretty soon, the Mohawk would return in overwhelming numbers. The mission was complete; they had bloodied the enemy’s nose on his home turf, and acquired captives. By the standards of Indigenous warfare, there was nothing else left to accomplish.

Speed rather than stealth marked the trip north back to the St. Lawrence. And within a few days, they were all going their separate ways. Iroquet and the Wendat turned west, toward the Ottawa River. They took with them the Mohawk captives, who’d either be tortured and killed as a means to enhance their captors’ prestige as warriors, or adopted into their captors’ Wendat society. Just as Champlain had hoped, they also took with them tales of French military power and generosity.

Meanwhile, the Frenchmen and the Innu warriors headed downriver. By now, it was August, and Champlain was due back in France in the Fall. He and de Mons would once again have to mount a desperate lobbying campaign to restore their monopoly.

But this time, Champlain had real results to report. With just a little bit more perseverance and material support, Quebec could become the central node of a vast commercial/diplomatic empire stretching deep into the continent. The alliances and trade network were already in place.