DEI

DEI’s Beleaguered True Believers, in Their Own Words

When ‘decolonial change alchemist’ Sabrina Meherally instructed her ‘white allies’ to divulge their pay rates and demographic details, many eagerly complied.

On 19 March, it was announced that the ten-campus University of California (UC) system would no longer require academic job applicants to supply so-called “diversity statements”—documents testifying to one’s embrace of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) as guiding professional values. The move made national news, both because of the size of the UC system, and because UC’s original adoption of diversity statements in the late 2010s had been instrumental in establishing a wider trend throughout academia.

That trend has been in decline since 2023, a policy reversal that is now accelerating thanks to the Trump administration’s strenuous opposition to DEI. In a parallel development, numerous corporations have been abandoning the DEI campaigns that they ramped up with much fanfare following the murder of George Floyd and the heyday of the Black Lives Matter movement in late 2020 and 2021.

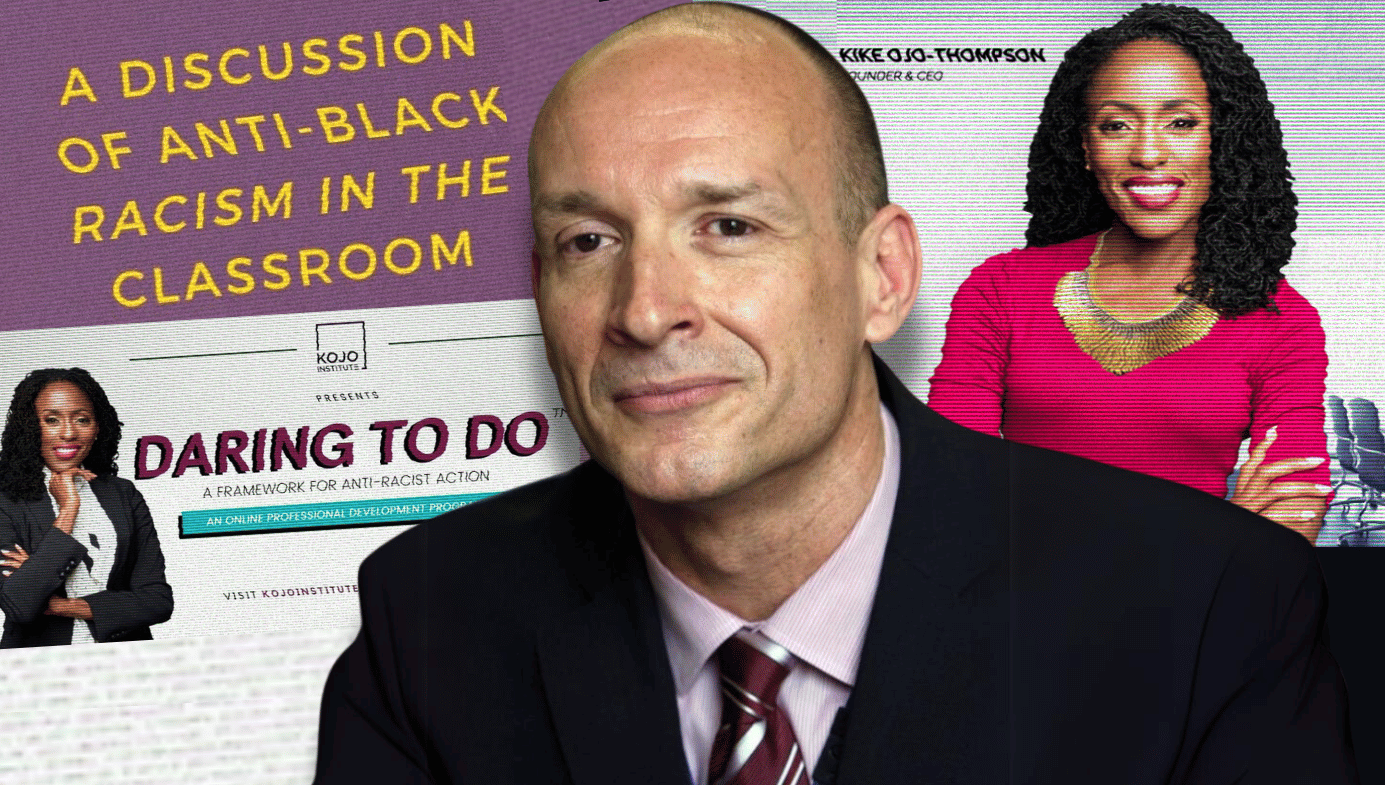

Even in highly progressive nations such as Canada, there are signs that DEI is coming to be seen as a tarnished concept (a development that DEI consultants, somewhat predictably, have denounced as a betrayal of Canadian values). In one widely reported scandal, a Toronto school principal committed suicide after he’d been falsely accused of white supremacist beliefs by a well-known DEI trainer named Kike Ojo-Thompson. In January, the University of Alberta became the first Canadian school to publicly reject its DEI framework (even if the school’s new “access, community, and belonging” paradigm would seem to incorporate some of the same principles under a new label).