Art and Culture

A Violent History Obscured

South Korean Nobel laureate Han Kang’s literary experimentation thwarts rather than advances her professed concern for the suffering of everyone, everywhere, all the time.

A review of We Do Not Part by Han Kang, 272 pages, Hogarth (February 2025)

“Here they come,” wrote Kingsley Amis of Colin Wilson’s debut book, the bold existentialist anthology, The Outsiders, “tramp, tramp, tramp—all those characters you thought were discredited, or had never read, or (if you are like me) had never heard of: Barbusse, Sartre, Camus, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Hermann Hesse, Hemingway, Van Gogh, Nijinsky, Tolstoy [and] Dostoevsky.”

This was textbook Amis. As a critic, novelist, and individual, he was a provocateur of a self-styled anti-highbrow stripe. His fellow Cambridge don in the 1960s, F.R. Leavis, is said to have called Amis a “pornographer” for his persistent low-browism, while British film critic and director Lindsay Anderson observed that Amis would “rather pose as a philistine than run the risk of being despised as an intellectual.” But Amis’s “cultivated philistinism”—his feigned ignorance of the canon and eagerness to scorn his own literary training—was more than mere schoolboy mischief. While habitually sticking his tongue out at high society, Amis was, at his best, making a literary point.

Amis’s style of criticism was colloquial, accessible, and did not require prior knowledge of literary theories or esoteric texts. As John McDermott wrote in his introduction to The Amis Collection, novelists (like the English Victorians) “trying to tell interesting stories about understandable characters in a reasonably straightforward style” were, in Amis’s view, successful. On the other hand, those—particularly the Modernists—who cultivated artistic detachment via obscurity, complexity, and other barriers to reasonable comprehension were merely fencing off their literary property or demonstrating their membership of a clique. This was just a kind of snobbery, Amis believed—the literary equivalent of accents, complicated table manners, and what-have-you.

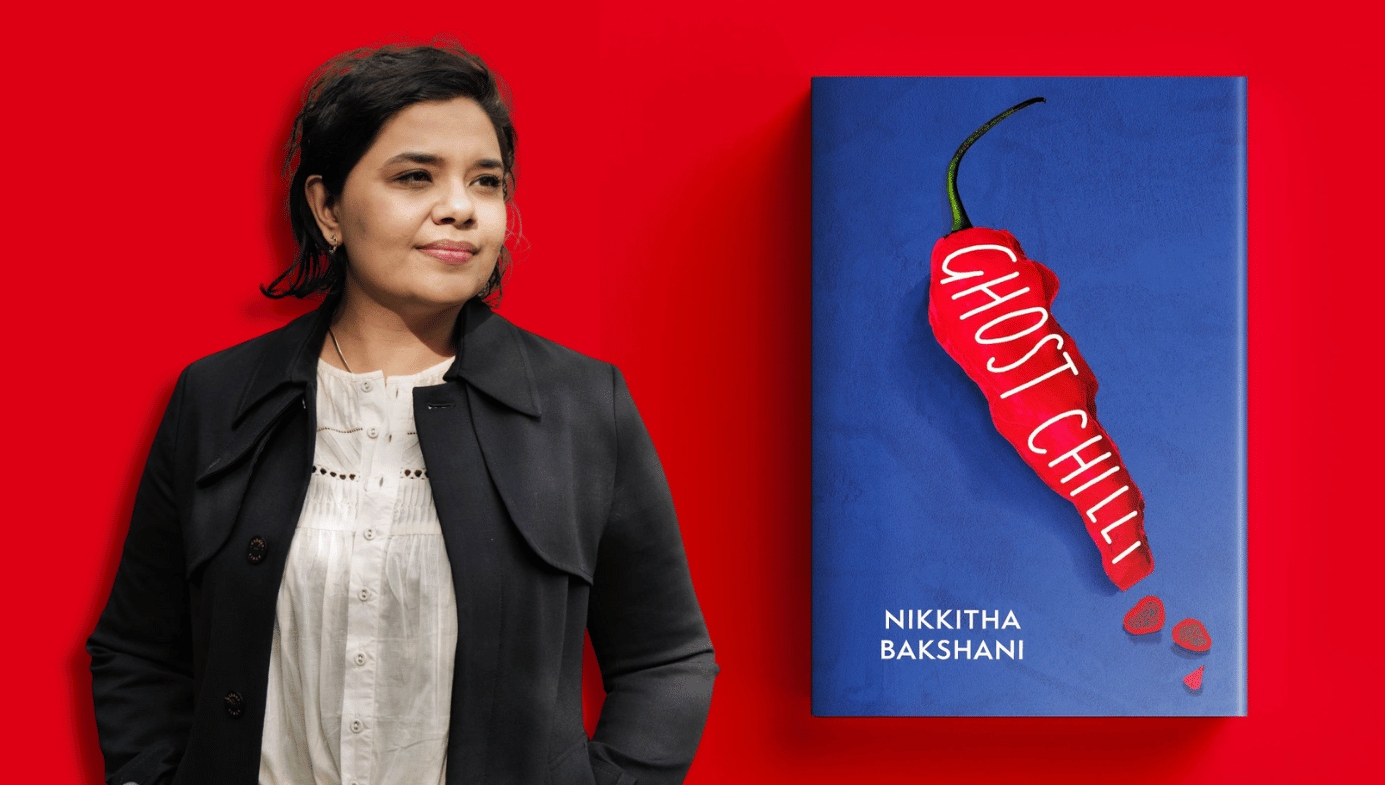

I thought of Amis as I read We Do Not Part, a 2021 novel by South Korean author Han Kang, republished in English translation this month. In literary circles, Kang is admired and rewarded for the kind of obscurantist sophistication that Amis disdained. She was last year’s Nobel laureate, but she first drew international acclaim with the publication of her 2015 novel, The Vegetarian, which won the Booker the following year. My misgivings about her style notwithstanding, Kang is an impressive and imaginative writer. She stretches quotidian premises to breaking point, condemning her unfortunate characters to inordinate suffering. The worlds she creates are surreally off-kilter, but they retain enough familiarity to be morbidly unsettling—The Vegetarian, for instance, is the story of a pliant woman violently shunned by her husband and family for giving up meat.

In We Do Not Part, the simple act of describing a dream to a friend is causally linked to the severing of fingers and a life-threatening voyage, first through a blizzard, then through space, time, collective memories, multigenerational trauma, and the like. The main action begins when Kyungha, an emotionally troubled writer living in Seoul, visits her longtime friend Inseon in hospital. Inseon, a filmmaker-turned-carpenter, has sliced off her fingers while felling trees to construct an elaborate movie set from Kyungha’s dream. Bedridden in hospital and in need of constant medical care, Inseon asks her friend to travel to her remote mountaintop home on Jeju Island to feed her pet bird, Ama.

Weak from delirium, Kyungha does not have the strength to refuse this request. She flies from Seoul to Jeju, where she journeys into the heart of her country’s suppressed history. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Jeju was the site of an uprising against newly imposed martial law, which led to mass executions of alleged communist sympathisers by the South Korean government. As soon as Kyungha arrives on the island, a heavy snowstorm sets in, and history as well as reality is buried beneath obscurity.

Kang is the pre-eminent chronicler of South Korea’s authoritarian 20th century, and she has come to be regarded as her country’s voice of conscience for her exploration of its bloody struggle for democracy. After writing Human Acts—an account of a student uprising and state-sanctioned massacre by the South Korean military in the city of Gwangju, where she grew up—Kang found herself haunted by a recurring dream, in which thousands of black trees on a snow-covered hill were pressed by a rising sea. That vision eventually led her, like her fictional counterpart, to Jeju.

While We Do Not Part shares themes with Human Acts, it is more oblique—only slowly during Kyungha’s mission are details about Jeju’s past divulged, and even these are filtered through multiple layers of novelistic abstraction. For instance, Kyungha meets Inseon—or Inseon’s ghostly apparition, it is never clear which—on Jeju. Inseon lights candles, opens folders, and recounts the history of her family and the island even though she remains confined to a hospital bed in Seoul. The past is not only illuminated by this possibly supernatural being, it is also drip-fed through various partial recollections, newspaper photographs, survivor reports, and family stories.

By burying evil in a labyrinth of meaning, Kang uses the form of the novel to express a number of interesting points about the difficulty of processing trauma and finding one’s way through suppressed historical material. The truth, it turns out, is often messy, second-hand, and worn-out through overuse. Some readers may find the novel’s atmospheric intensity and dream-like quality rewarding, but I found that it diminished the emotional weight of the atrocities the author and her protagonist uncover. It was only after I finished the novel that its literary tricks became apparent, by which point bewilderment had already given way to frustration.

Charitably summarised, We Do Not Part is a book about the difficulty of looking at history that makes looking at history difficult. But I kept stubbing my toe against the experimental trickery and technical tomfoolery, unable to care about the Jeju massacre or our near-suicidal writer-narrator. Kyungha can’t tell if it’s drowsiness or a layer of ice that is keeping her eyes closed. She doesn’t know if she’s lying in a stream or if she’s standing upright, whether or not frostbite has set in, whether or not this is what happens right before you die. Kyungha clearly wants to die—she talks about it a lot—and wonders if she has come to Jeju to do so.

Kang refuses to be clear about which events are real in the world of her story. She blurs the dead with the living, those who are asleep with those who are awake, strangers with friends, weather with human actions, personal torments with historical atrocities, and the concrete with the supernatural. These oppositions are kept in dizzying tension but they are never reconciled in a satisfying way. That the best novels attempt only provisional conclusions and dwell in moral ambiguity is true. Yet applying this principle to storyworld metaphysics risks losing the reader; fill the tank with too much of this representation-of-meaning-at-the-level-of-form stuff, and the motors of fiction break down.

We Do Not Part trades in big existential ideas, consistent with Han Kang’s central project of eliciting radical empathy with “everyone who’s ever suffered … regardless of place.” Like The Vegetarian before it, We Do Not Part is preoccupied with the need to feel empathy for strangers. Kang likes to contrast the imperfect affection we feel for those close to us with the instinctive indifference we feel about the suffering of those we do not know, only to undermine the stability of that contrast. She draws attention to the limits of human empathy in an attempt to expand them; she does not deny moral limits, but she asks us to behave as if those limits do not exist.

Kayunga is initially afflicted with the solipsism of the suicidal, but there is a point at which the absurd task of rescuing her friend’s pet bird becomes more important than her own struggle for survival. We are invited to question whether love for another can provide life with meaning. Given Kang’s metaphysical ambiguities, however, we also question whether this feeling is fundamentally an illusion; and if it is, are these illusions worth believing in anyway? Interesting questions, no doubt. But Beckettian existential angst drowns the texture of the novel and dilutes the more compelling subject at its centre.

The repression of history in the South Korean consciousness is undoubtedly worth excavating, and Kang has a brilliant mind well-equipped for the task. Yet this remains a book unwilling to share its secrets. Digging up history’s forgotten victims only to rebury them beneath layers of novelistic abstraction is a curious way to make the historically illiterate reader—like me—care about people and events so far removed from our immediate concerns. Yes, language may “connect us to one another,” as Kang sonorously proclaimed in her Nobel acceptance speech, but it can also divide us with such high barriers to entry.

Though her work is not political in a narrow sense, it is finally worth noting that Kang’s philosophical priors and guiding project of radical—or even pathological—empathy do seem to align with the broader enterprise of the global Left: a bloodless, abstract empathy for everyone, everywhere, always; a purely rational love divorced from its commonly understood meaning and from our natural affections and limits. There may be a way to convince me of this utopian possibility. There is definitely a way to deal with this harrowing historical material. But Kang’s exercise in literary experimentation thwarts rather than advances her concern for the suffering of everyone. In the end, like the depressed writer at the novel’s beginning, I cared for nothing but myself.