Australia

Australia Day Dreaming

On Australia Day, we should recognise the blackfellas, the whitefellas, and the fellas of all shades in between.

Australia Day 1988 was a party.

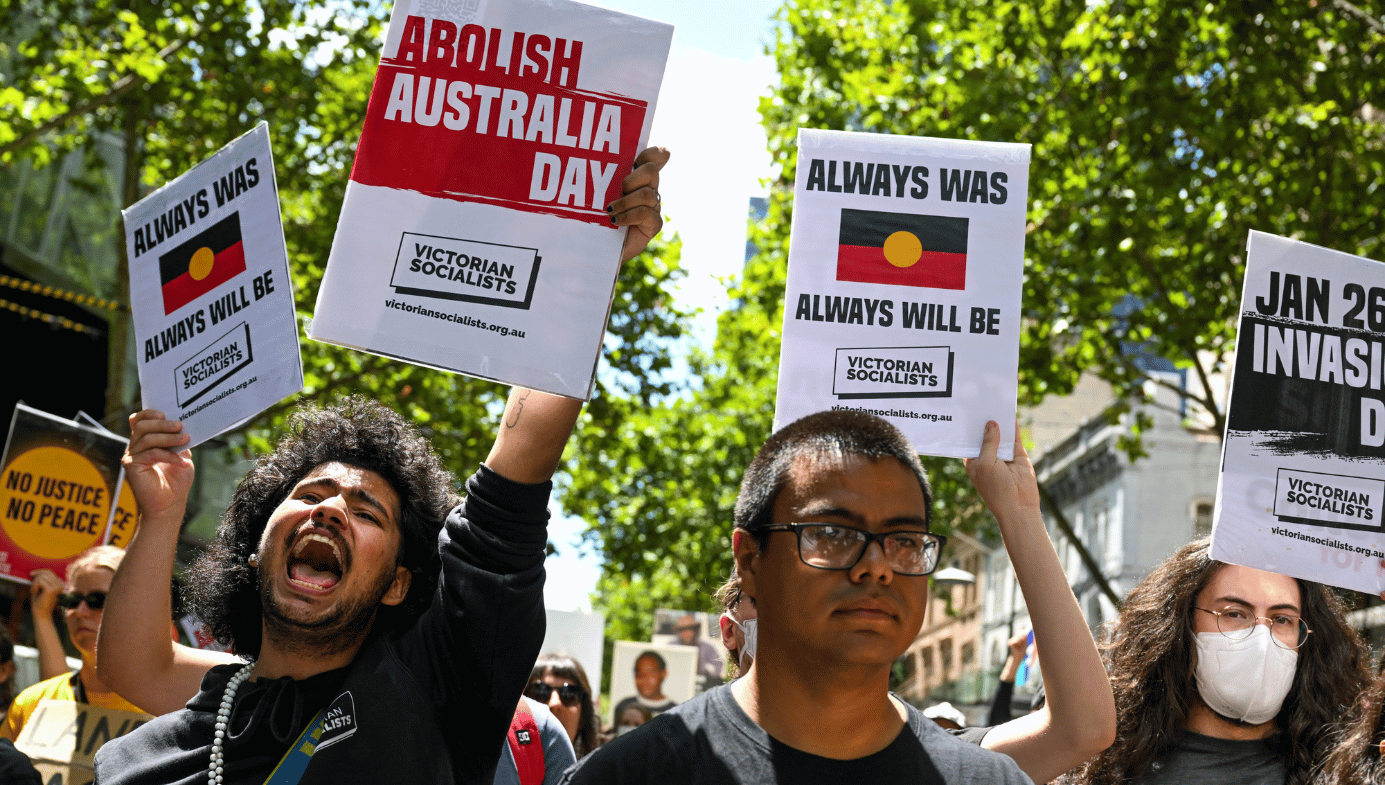

There was also a demo, of course. Protests on Australia Day have been a thing since the first Day of Mourning in 1938. A few thousand protestors gathered around Mrs Macquarie’s Chair, a high vantage point half a kilometre east of the iconic Sydney Opera House, from whence they could boo the First Fleet re-enactment as it sailed past. Worried about indigenous sensitivities, the Labor Government of Bob Hawke had refused to fund it. The shock jocks of the 2GB radio station had stepped in to keep the re-enactment afloat. The protestors waved banners and made noise about Invasion Day. Most people ignored them.

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of people—blackfellas, whitefellas, yellafellas and olivefellas—gathered around Sydney Harbour, not to protest, but to see the tall ships, catch a glimpse of the most photographed woman on Earth—HRH Princess Diana, she of the fairytale wedding—and watch the fireworks.

I had been lucky enough to score a ticket to the Opera House enclosure. No fighting to get to a bar or Portaloo in the unticketed wilderness for me. As a result, I was about twenty metres from Charles and Diana when they caught a boat over to the Opera House from Admiralty House and walked into the exclusive ticket zone. I chatted politely with one of the pyrotechnic engineers. He mentioned that the biggest firework in the forthcoming show was going to be a 19-incher made by a pyromaniac in Japan. I was seriously impressed. The main armament of the biggest battleship ever made, the Yamato of the Imperial Japanese Navy, consisted of 18-inch guns. A 19-inch firework would be one heck of a projectile.

Hours later, I was still in that prime Opera House spot when the fuses were lit. The engineers had spent a whole week in a covert operation to wire up the Harbour Bridge without the media getting wind of it. As a result, people were stunned when the bridge erupted in phosphorus. You could hear a sharp collective intake of breath. Back then, lighting up the bridge was not the annual New Year’s Eve firework story it is today. The surprise was complete. The 19-incher that ended the display was similarly awesome. Before it was set off, there was a pause, long enough to make people think the fireworks were done, then a dull thud and a couple of seconds later a massive bang. Incandescent lines, like the spokes of an umbrella, lit up the sky. Another gasp. Standing right underneath, at the Opera House, it seemed as if the lines of phosphorous spanned the ten kilometres from Point Piper to Balmain.

I remember listening to a fruity ABC commentator on the loudspeakers introducing some specially composed Australian music, which he described as “fabulous.” It was so fabulous I have never heard it played again. I chugged a few coldies and spared no thought for what Australia Day meant for the Aborigines. Back then, I did not know any. For me, Australia Day was a party. Bicentennial Day was a particularly memorable one.

At around 4:30 am on a Sunday morning some weeks later, I picked up a fare from Chatswood to Caringbah. At that time of day, it was a very nice job: a long drive of about 45 minutes. My passenger was an Aboriginal man called Burnum Burnum, who hopped into the front seat to talk to me. This was the first extended conversation I had ever had with an Aborigine. The darkness of his skin contrasted with the whiteness of his hair.

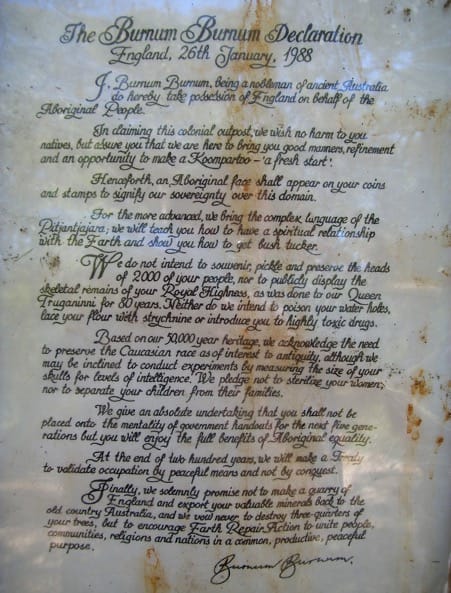

Our conversation was more of a monologue. Burnum did most of the talking. On Australia Day, he was not on Sydney Harbour, demonstrating at Mrs Macquarie’s Chair. He was on a boat in the English Channel, just south of the White Cliffs. After landing on Dover Beach and planting an Aboriginal flag in the sand, he read out a proclamation, claiming England for the Aboriginal people and promising to teach the natives manners and such.

He got coverage on Australian media, which I remembered. He told me he got big coverage on Soviet media. Apparently, he was the number three story on TASS, the party-run news agency. TASS, of course, was delighted to run a story on imperialist running dogs being taught manners by an Aborigine.

His declaration makes entertaining reading. He promises not to “souvenir, pickle and preserve the heads of 2000 of your people” and not to “poison your water holes, lace your flour with strychnine, or introduce your people to toxic drugs.” His “absolute undertaking” not to instil in the British the “mentality of government handouts for the next five generations” is economically sound.

Burnum Burnum was a character. In addition to filling me in on his media stunt, he ranted at some length about people he called “milkies.” Burnum Burnum was what used to be called a “full-blood” black. The “milkies” that he spent much of the ride deriding had, in his mind, succumbed to the “white man’s poisons” (tobacco and grog), resulting in the worst possible combination: the Irish love of alcohol and the Aboriginal inability to handle it.

These days, a bloke can get cancelled for disputing the blackness of people with just one or two black grandparents. It’s a touchy subject. I daresay if Burnum Burnum published his views on mixed race Aborigines, grog, and smokes today, he would get cancelled but he died in 1997, long before cancel culture became a thing. He got an obituary in the New York Times. That stunt on Australia Day 1988 was remembered years later.

26 January 1788 was a party, too. Contrary to popular belief, this is not the date on which the Colony of New South Wales was proclaimed or founded. Nor is it the date the First Fleet arrived in Australia. It is not even the date the convicts got off the boats. As the historian Henry Reynolds observes in Truth-Telling: History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement, nothing of legal consequence happened. It is, however, the date when Captain Phillip had his men fell some trees and raise a flagstaff at Sydney Cove. In the evening, officers hoisted the Union Jack and drank toasts to the health of the King and the success of the Colony.

Today, 26 January is called “Invasion Day” by some activists. From their point of view this is understandable, but compared to the fleet that invaded New France (Quebec) in 1759, the First Fleet cannot be called an invasion fleet. It consisted of several shiploads of convicts and a small number of guards. In 1778, there was no storming of Sydney Cove. Bluejackets and redcoats did not row onto the beach in the face of bitter and determined Aboriginal resistance. The air was not thick with spears. No Aborigines were shot. The beach did not run with blood. The Aborigines kept their distance.

Captain Phillip did not get around to officially “proclaiming” the Colony until 7 February. As Reynolds observes, it was on this date that “the formal ceremony of annexation was conducted before the whole population” and the British “took possession of the colony in form.” Phillip assembled the convicts, read out the proclamation, and became governor of the colony with authority granted to him by letters patent from the Crown.

Weeks later, he exercised his judicial power as governor to hang a convict for stealing food. Initially, Phillip did not engage in significant hostilities against the Aborigines. He kidnapped Bennelong in November 1789 because he wanted to establish communications with them. It is not possible to negotiate a treaty when neither party speaks the other’s language. Bennelong learnt English and acquired a taste for the white man’s poisons—grog and tobacco—but he ran away in May 1790.

Phillip and Bennelong met again at Manly Cove in September, where Phillip was speared by an Aboriginal warrior called Willemering. Other spearings followed. In December 1790, Phillip ordered his Captain of Marines, Watkin Tench, to embark on two punitive expeditions to punish Aborigines for spearing convicts. They were complete failures. Naked, highly mobile Aborigines were able to evade lumbering redcoats loaded with backpacks of rations as they hauled muskets and ammunition through the unmapped bush.

Correctly understood, Australia Day is not the date of colonisation, nor the date of conquest, nor even the date on which white people started shooting black people. Phillip whipped and hanged white convicts long before he ordered the shooting of blacks. 26 January is simply the date of the first party of consequence involving alcohol in the entire 50–60 odd millennia of the mostly unrecorded history of human settlement in Australia.

I daresay it was a good one. The daily ration of rum for a sailor in the Royal Navy at that time was a half pint per day (300 ml). In modern Australia a “standard drink” is 30 ml of 37.5 percent proof rum. So a half pint is 10 shots. When one makes allowances for the greater strength of eighteenth-century Navy Rum (over 57 percent), it’s a few shots more. The sailors of 1788 would reject the watered-down 37.5 percent proof rum sold today as failing the “proof test.” This consisted of pouring rum on gunpowder and trying to ignite it. If it failed to flare, the rum was considered to have been watered down. I suspect that after several months cooped up on ships, the officers might have helped themselves to more than one day’s ration of grog on the day. In truth, Australia Day commemorates a drinking party. Given this, one answer to the question “how should we celebrate Australia Day?” is simple. The historically accurate and culturally appropriate thing for a whitefella to do is to run up the flag, toast the health of the King, and drink rum.

So, should we celebrate Australia Day? What are we celebrating? When should we have it? Should we change the date?

Many people make grand claims about “the soul of the nation” or wring their hands about how we have to “come to terms” with our past. And that past did contain a great deal of ugliness. It is true that white women on occasion poisoned blacks by putting strychnine in flour and that white men, early in the colonial period, improvised death squads that massacred black men, women, and children in dawn raids. Later in the colonial period, the infamous Native Police—black men armed and paid by white men—rode out on horses to hunt down and kill black men who had slaughtered white-owned stock and murdered white (and black) stockmen. It is also true that most black people in remote Australia today remain poor because Aboriginal land title is comparable to Soviet land title—purely nominal—and the result in both cases is systemic poverty. Are these the things we want to remember? Do we want Australia Day to be a sombre memorial, a National Day of Guilt on which the people must wear sackcloth and atone for the sins of their great-great-grandfathers—or do we want it to remain a party? Given that the only thing that actually happened on the day was running up the flag and toasting the health of the King and the success of the Colony by drinking rum, I move the party continue but with a slight date change.

We should maintain a connection with the anniversary of the First Party but as Noel Pearson—another Aborigine who, like Burnum Burnum, has a sound loathing of the “sit-down money” of chronic welfare dependency—suggests, why not also celebrate on the day before? Pearson suggests a second holiday on 25 January to recognise those who were here before the whites arrived, i.e. the Aborigines and the Torres Strait Islanders. Fair enough—but what about all the people who landed after the whites? I suggest we keep a single holiday that recognises all three of the “great stories” of Australian history Pearson writes about in his book, Mission. These are: “the ancient Indigenous heritage that is Australia’s foundation, the British institutions built upon it and the adorning gift of multicultural migration.” On Australia Day, we should recognise the blackfellas, the whitefellas, and the fellas of all shades in between.

This year the holiday falls on 27 January because 26 January is a Sunday. It has long been routine to push public holidays to Monday if they fall on a weekend. So, at present, two out of seven Australia Days do not happen on the exact anniversary of the First Party, they happen on the Monday after. In future, we could make Australia Day the Monday or Friday before or after the anniversary, except when it falls on a Monday or Friday.

My thinking is that having Australia Day on the anniversary marks white settlement, having it before marks indigenous settlement and having it after marks multicultural settlement. To celebrate on all three days is to treat us all equally, as we should since all our ancestors are migrants. We could have two out of seven before the day (for the blackfellas), two out of seven on the day (for the whitefellas) and three out of seven after the day (for the yellafellas, the olivefellas, the brownfellas, the occasional redfella and, of course, non-indigenous blackfellas and non-British whitefellas).

This would mean only two out of seven Australia Days would happen on the actual anniversary. This would give us a consistent long weekend at the end of January, instead of a public holiday in the middle of the week, three years out of seven. That would be a vote winner; Australians love a long weekend. It gives us an extra day to recover from the exertions of the party or to unwind and chill.

|

Anniversary |

Holiday |

Shift |

|

Sunday 26th |

Friday 24th |

Before |

|

Monday 26th |

Monday 26th |

On |

|

Tuesday 26th |

Friday 29th |

After |

|

Wednesday 26th |

Friday 28th |

After |

|

Thursday 26th |

Friday 27th |

After |

|

Friday 26th |

Friday 26th |

On |

|

Saturday 26th |

Friday 25th |

Before |

Table 1: Australia Day as a Long Weekend for Symbolic and Practical Reasons

One of the ironies of the great success of the Bicentenary celebrations is that it encouraged the states to align on celebrating the actual anniversary rather than having a long weekend. Prior to 1994, states often set the Australia Day public holiday on a Monday in late January. I move we return to the practice of making Australia Day a long weekend for symbolic and practical reasons.

Of course, changing the date of Australia Day does nothing to address economic problems and other issues that result from poverty and isolation such as higher rates of crime, violence, child abuse, neglect, and lower rates of educational attainment, employment, and business ownership. Moving the holiday is purely symbolic but there is nothing wrong with that. Nations need symbols they can unite around. My proposal, adapted from Pearson’s, is minimal and practical. Let’s make Australia Day a moveable feast: a day for all Australians, be they black or white, old or new.