democracy

The Year of Elections

An unprecedented number of elections took place in Africa, Asia, and Latin America this year. Their results suggest that prospects for democracy are mixed.

More people voted in 2024 than in any previous year in history: at least 76 countries—representing more than half the world’s population—will have held elections by the end of the year. By September, at least 67 countries had held national elections, including heavyweights like Indonesia, Pakistan, India, Mexico, and the United Kingdom.

So do the results of these elections signal a turning point in the “democratic recession,” which has characterised global affairs for the last two decades?According to the nonprofit Freedom House, freedom and democracy have been on the retreat since 2006. Across the developing world in particular, authoritarian populists have won at the ballot box and set up what political scientists Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way have termed “competitive authoritarian” regimes, in which autocrats hold elections to grant themselves legitimacy while stacking the deck against their opponents through their control over vital institutions such as the media, judiciary, legislature, and the civil service.

An analysis of the recent elections in Africa, the Asia-Pacific, the Indian subcontinent, and the Americas suggests mixed prospects for democracy. In many countries, authoritarian populists managed to consolidate their power through the ballot box. In others, they either lost or had their margins of victory reduced. Many states that had been dominated by a single party for decades have now entered a more competitive era of politics, as their populations have voted for change. As Thomas Carothers, director of Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program, has observed, “[t]he year of elections can be understood as a telling reflection of the overall uncertain direction of travel of the global state of democracy. After many years of a widening democratic recession, a sense of plateauing has occurred.” Given their rising demographic, economic, and geopolitical profiles, the countries of the developing world provide key indicators of whether the borders of the democratic world will expand or contract in the coming years.

Africa

An unprecedented number of elections took place in Africa this past year, providing some glimmers of hope for the long-term future of African democracy, amidst a resurgence and normalisation of military coups in recent years. As these elections show, a confluence of robust civil society, strong institutions, and effective opposition can help peacefully oust even entrenched incumbents.

For example, in March, Senegalese voters elected opposition leader Bassirou Diomaye Faye. At 44 years old, Faye is Africa’s youngest serving president. In the weeks preceding the election, the country was plunged into a constitutional crisis when then-incumbent Macky Sall attempted to postpone the presidential election to December, thereby effectively extending his tenure beyond its five-year term, which ended on 2 April. Had he succeeded, he would have contributed to a larger trend of African leaders evading or outright abolishing term limits in order to remain in power. This wasn’t the first time Sall had attempted to extend his time in office beyond the constitutional limits—his 2023 attempt to run for a third term mobilised civil society against him, causing him to eventually back down in the face of violent protests.

Sall’s announcement that he intended to delay the 2024 elections triggered mass demonstrations. The state responded by cutting mobile internet access and deploying large numbers of police to its major cities. Four people were killed in clashes with the police. After Senegal’s Constitutional Court overturned Sall’s attempts to delay the election, the president finally announced that elections would take place on 24 March.

Faye’s eventual victory was all the more remarkable given that, only ten days previously, he had been a political prisoner, having been arrested in April 2023 on charges of defamation, contempt of court, and “acts likely to compromise public peace.” After Sall failed to delay the election, he passed an amnesty law to protect himself from legal reprisals once his term ended. The amnesty law also guaranteed immunity for all perpetrators of violence at political demonstrations held between 2021 and 2024. Thanks to the new law, Faye was released from prison on 15 March, ran in the presidential election, and secured 54.28 percent of the vote.

In the democracies of southern Africa, incumbents were also ousted: in this case, the ruling factions had been part of Former Liberation Movements that had brought their respective countries independence and ended colonialism and white minority rule. They had held power ever since. However, decades of uninterrupted rule have left all the countries of southern Africa with poor governance, creeping autocracy, corruption, economic stagnation, unemployment, and a lack of economic diversification. As a result, public support for the Former Liberation Movements has started to ebb, particularly among younger voters—the “born-frees”—who are not influenced by nostalgia for the liberation struggle.

In May, South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) lost their majority in the legislature, which forced them to form a coalition government with their erstwhile rivals the Democratic Alliance (DA). In October, the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which had held power since independence from Britain in 1966, suffered a catastrophic defeat in the general elections, losing all but four of its 38 seats, and ceded power to the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC).

In presidential and parliamentary elections held in Mozambique that same month, the national electoral authority declared an overwhelming victory for the ruling Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) and its presidential candidate, Daniel Chapo. FRELIMO has governed Mozambique since its independence from Portugal in 1975. But Chapo’s opponent, pastor and former radio host Venâncio Mondlane, claimed victory on the grounds of a partial count conducted by his own electoral team, which gave him a majority. Independent observers, including the Episcopal Conference of Mozambique and the European Union, also reported evidence of electoral fraud. Mondlane’s supporters have taken to the streets where, amid violent clashes with police, they have brought many parts of the country to a standstill. The ongoing demonstrations, which began with credible allegations of electoral fraud, have morphed into a broader show of dissatisfaction with FRELIMO rule.

The most recent southern African country to hold elections was Namibia on 27 November. The ruling South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO), in power since independence from South Africa in 1990, suffered its worst electoral showing, securing only 51 of the 96 elected seats in parliament after winning 53.4 percent of the 1.1 million votes cast—a drop from the 65.5 percent secured in 2019, when SWAPO first lost its two-thirds majority in parliament. The downward trend in support for SWAPO since 2019 was confirmed by dramatically poor showings in the 2020 regional and local elections. While SWAPO candidate Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah was voted in as Namibia’s first female president in the 2024 election (winning more than 57 percent of the vote), her victory and that of her party were tarred by allegations of widespread irregularities, evidenced by logistical problems and the introduction of a three-day polling extension in some parts of the country. As SWAPO member Henning Melber has observed, “[i]n urban centers in particular, voters have turned their back on the former liberation movement because of a lack of delivery.”

On 13 November, the people of Somaliland, the breakaway region of northern Somalia, went to the polls. Having declared independence from Somalia in 1991, Somaliland has managed to build a relatively stable democracy in a part of the world where autocracy is the norm. The unrecognised breakaway region now possesses all the trappings of a sovereign state, including a functioning government and institutions, its own currency and security services, and a political system that allows for the peaceful transfer of power.

Opposition candidate Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi (“Irro”) won a convincing victory over incumbent president Muse Bihi, obtaining 64 percent of the vote in Somaliland’s fourth successful one-person, one-vote presidential election since breaking away from Somalia. As commentator Brendon J. Cannon has argued, Irro’s victory “shows Somaliland’s democratic resilience and potential for inclusive governance.” Like his predecessor, Irro is committed to securing international recognition for Somaliland. The election of Donald Trump may facilitate this, given that many within Trump’s circle view the breakaway region as a more dependable US ally than Somalia.

South Asia

Two major elections took place on the Indian subcontinent this year: in Pakistan in February and in India between April and June. Both resulted in surprising losses for the country’s respective incumbents, despite the fact that they presided over democratic systems stacked against the opposition. Both electoral upsets were largely driven by failures to provide effective governance or tackle major economic challenges—to the detriment of the countries’ young and restless electorates.

Pakistan’s February elections took place amid a deteriorating democratic environment. Much of the decline can be blamed on Pakistan’s all-powerful military-intelligence apparatus, often euphemistically referred to as “the Establishment.” The country has been under direct military rule for more than 30 of its 77 years of existence. Intermittent civilian governments have only been possible with the military’s backing: civilian leaders have been forced to operate within the parameters set by the Establishment.

In 2018, the generals helped install former cricket superstar Imran Khan as prime minister. A self-proclaimed reformer, Khan gained a devoted following, particularly among young and middle-class Pakistanis. However, relations between Khan and the Establishment soured when the economy underwent a severe sovereign debt crisis in the aftermath of the global pandemic. The final straw was Khan’s interference in the selection of a new head of the intelligence services. In response, the military engineered a parliamentary vote of no confidence against Khan in April 2022, thus ousting him from power. Since August 2023, Khan has been imprisoned on an ever-increasing list of charges. He was disqualified from running in the 2024 election cycle and his party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (“Pakistan Movement for Justice,” PTI), was shut out of the election on procedural grounds, forcing its candidates to run as independents. In 2023, the PTI was severely repressed: thousands of party members were jailed and almost all its senior leaders were pressured into quitting politics. The coalition that formed following Khan’s ouster—comprising the military-backed dynastic parties the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP)—was widely tipped to win.

Instead, the independent candidates backed by the PTI won a plurality, though not an outright majority, of the votes: 93 out of 266. The PML-N and PPP won 75 and 54 seats respectively. While the two parties were able to cobble together a minority government, the PTI’s strong performance—in the teeth of an exceptionally heavy-handed crackdown—demonstrated the extent of public dissatisfaction with the status quo. As commentator Madiha Afzal has argued, this shows that the already frayed compact between Pakistan’s citizens and the once-respected Establishment has been broken. Nor has the February election brought political stability. The PTI have been protesting the election results both on the streets and in the courts amidst widespread allegations of election rigging. From his prison cell, Khan may well have upended Pakistan’s traditional power structure.

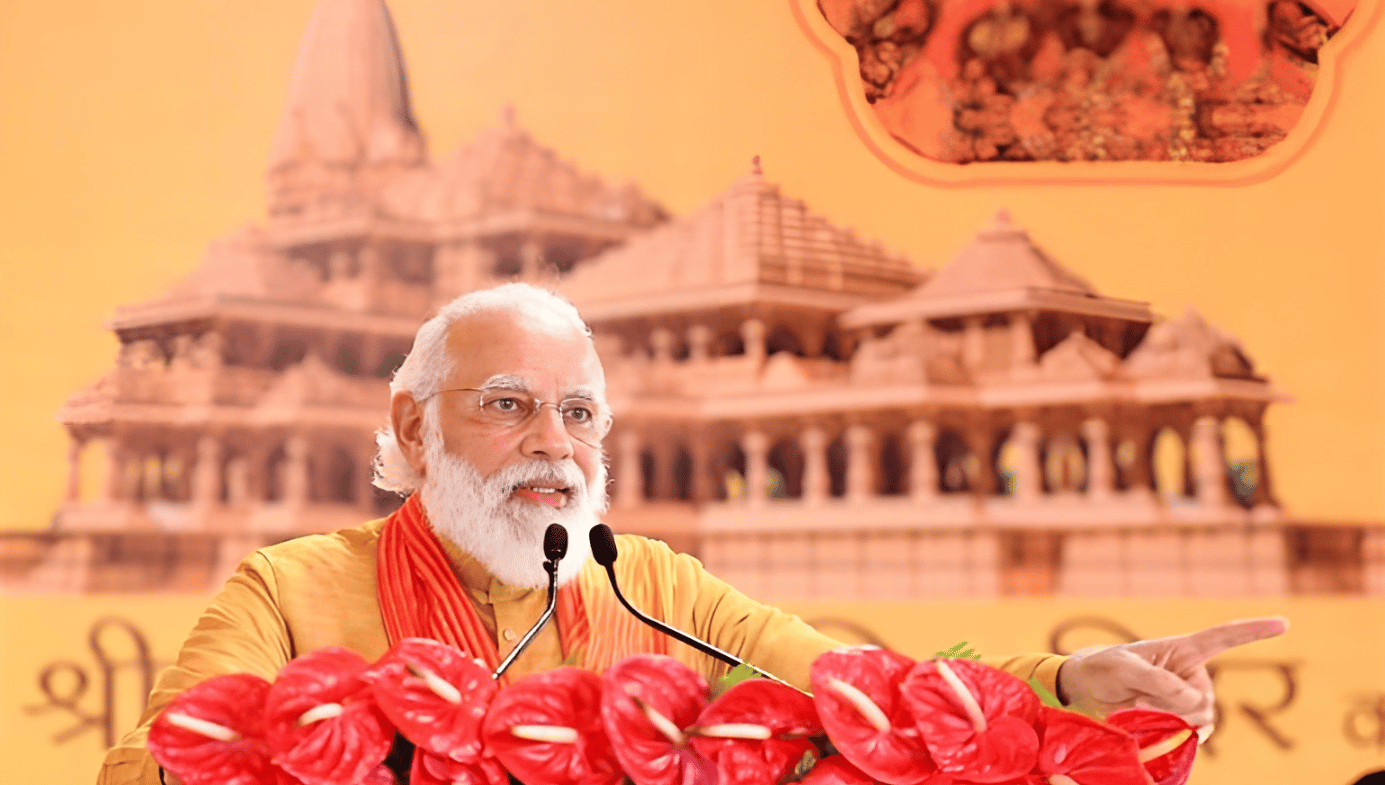

In neighbouring India, the world’s largest democracy, the results of the massive general elections that took place in seven phases between 19 April and 1 June also caught everyone off guard. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was widely expected to win a third consecutive single-party majority in India’s lower house of Parliament, the Lok Sabha, building upon its absolute majority of 303 seats secured in the 2019 elections (272 seats are needed for a majority in the 543-seat Lok Sabha). So sure were the BJP of another landslide victory that they went to the polls with the slogan “Abki Baar 400 Paar” (“this time, more than 400 seats”). Another large majority of that kind would have permitted Modi to continue pursuing his muscular Hindu nationalist vision for India, at the expense of India’s secular character and its religious minorities, particularly its 200 million strong Muslim community.

Instead, the BJP ended up losing its majority, securing only 240 seats. In total, the BJP and its ally the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) secured 293 seats, while the 28-party opposition coalition, Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), led by the Indian National Congress, performed much better than expected, securing 234 seats. The Congress Party itself secured 99 seats, nearly doubling its 2019 tally. The BJP’s vote share declined in its traditional bastion, the Hindi-speaking heartlands of northern India. In Uttar Pradesh—India’s largest state—the BJP’s share of the state’s 80 parliamentary constituencies fell from 63 to 33. In Modi’s own seat of Varanasi, his personal majority dropped from 479,505 to 152,513. His opponent, INDIA bloc candidate Ajay Rai, referred to his own defeat as a “moral victory.”

The most important cause of the BJP’s weak performance has been the government’s poor handling of the economy. Despite glowing official reports and foreign media narratives of a booming economy, observers warn that jobs, consumption, and exports remain low. The ability to produce enough desirable jobs—particularly for India’s more than 600 million youth—remains the country’s principal challenge. By one count, an astonishing 44 percent of Indians in the 20–24 age group are unemployed and even more are probably underemployed.

Having lost his majority, Modi is now dependent upon his allies within the NDA to govern. This will require a significant change in his style of governance. The period during which the BJP enjoyed a single-party parliamentary majority was characterised by the centralisation of power and an authoritarian governing style. A cult of personality developed around Modi, whose face appeared on everything from COVID-19 vaccine certificates to fertiliser bags. Over time, this began to veer into the realm of the absurd—in May, the prime minister even suggested that rather than having being born “biologically,” he had been sent by God. During his first two terms in office, Modi eschewed a consensus-based approach to policymaking in favour of shock and awe. Major national decisions such as the revocation of the special status of the territory of Jammu and Kashmir and the demonetisation of certain currency notes were made without any input from other senior cabinet members.

Now Modi will have to accommodate the priorities of his coalition partners. Progress on sensitive economic reforms, such as changes to land acquisition or labour laws, is likely to become even more challenging. The BJP will also find it more difficult to pursue divisive sectarian-driven policies such as implementing a uniform civil code or adopting the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act 2019. Modi will also be forced to tolerate more criticism and public debate than he did during his previous tenures.

Asia Pacific

Indonesia held presidential and legislative elections in February. These elections were an epic logistical feat, as befitting the world’s third-largest democracy. Some 168 million Indonesians cast their votes in a remarkable 82.4 percent electoral turnout. Former army general Prabowo Subianto won a landslide victory, securing 58.6 percent of the vote—some 96.2 million votes. His closest opponent, former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan, secured 24.9 percent, 40.9 million votes.

Prabowo’s victory has engendered consternation about the future of Indonesian democracy. A former son-in-law of the dictator Suharto, Prabowo rose to prominence under his father-in-law’s authoritarian New Order regime (1966–98). As a former special forces commander, Prabowo has been accused of having been involved in human rights abuses during Indonesia’s occupation of Timor-Leste (1975–99) as well as in Papua. In May 1998, special forces under his command reportedly abducted democracy activists in Jakarta during the riots that led to Suharto’s downfall. Prabowo has made no secret of his distaste for democracy, calling it “very tiring,” “very messy and costly.”

Prabowo has also benefitted from the decade of democratic backsliding that occurred under his predecessor, Joko Widodo (commonly referred to as “Jokowi”). During Jokowi’s two terms in office, he oversaw the weakening of institutions like the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) and suppressed public dissent. As Jokowi approached his term limits, he sought a successor who would continue his legacy and whom he could influence from outside office. He settled on Prabowo, his then-Defence Minister and former rival for president, during his successful 2014 and 2019 presidential bids.

Jokowi’s support for Prabowo seems to have led to some legal chicaneries. In October 2023, the Constitutional Court—then chaired by Jokowi’s brother-in-law—lowered the age limits for candidates in the upcoming election. It is widely believed that this was done at Jokowi’s behest, to allow his 36-year-old son Gibran to be Prabowo’s running mate. Prabowo’s choice of Gibran as vice-president proved crucial to his eventual victory, as Gibran brought him additional support from Jokowi’s backers.

The long-term stability of Prabowo’s government will hinge upon the relationship between Jokowi and Prabowo. During the election campaign, Prabowo pitched himself as the continuity candidate, insisting that he would not diverge from Jokowi’s policies. Yet, it seems doubtful that someone as hot-headed as Prabowo will remain content to be Jokowi’s puppet. As the Indonesians put it: “Can there be dua matahari (two suns)?”

Latin America

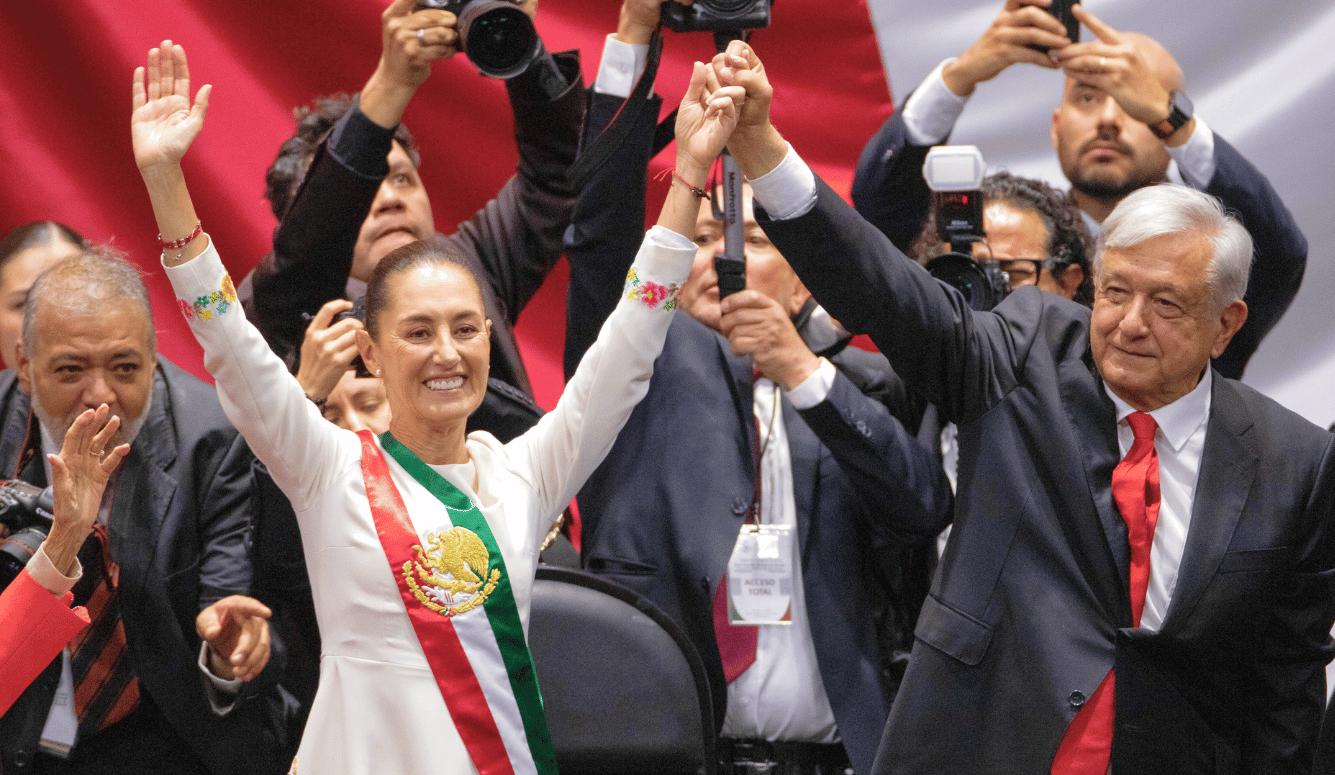

The two major elections that took place in Latin America this year—in Mexico and Venezuela—send contrasting signals about the future of Latin American democracy. In Mexico, the victory of continuity candidate Claudia Sheinbaum of the Morena Party suggests that voters continue to prioritise populism and redistributive social policies over institutional health. On the other hand, in Venezuela, the apparent victory of opposition candidate Edmundo González over dictatorial strongman Nicolás Maduro indicates that a determined and well-organised opposition can still triumph over even the most repressive of autocratic regimes given the right circumstances.

On 1 October, Claudia Sheinbaum was inaugurated as Mexico’s first female president, having won a landslide victory in a general election held on 2 June. A former mayor of Mexico City, Sheinbaum secured nearly 60 percent of the popular vote—the highest percentage secured by any president since Mexico’s transition to democracy in 2001. Sheinbaum’s party, in coalition with the Green Party and the Workers’ Party, won two-thirds of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies and was only one vote shy of achieving a supermajority in the upper chamber.

This dominance means that Sheinbaum will face little opposition in continuing her predecessor and mentor Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s so-called “Fourth Transformation,” a planned social and political restructuring designed both to economically empower the country’s marginalised through redistributive policies and weaken its system of checks and balances.

The latter aspect of López Obrador’s “Fourth Transformation” has raised alarm bells about the health of Mexican democracy. Since he was elected in 2018, López Obrador has been following an agenda of institutional destruction. He has couched his project in populist terms—railing against neoliberalism and promising to bring down the elites. Rather than being a lame-duck president following the June election, López Obrador used his remaining three months in office to ram through major constitutional reforms that have further weakened Mexican institutions. As Mexican lawyer Emiliano Polo has observed, these reforms targeted “the few remaining free spheres of political autonomy and professionalism that could not be subjugated during López Obrador’s administration.”

The most consequential of these reforms concern the country’s judiciary. Nearly seven thousand state and federal judges are slated to be replaced by popularly elected ones. Critics have warned that this will incentivise judges to decide cases on the basis of political factors, rather than judging each case on its own merits. In addition, since judicial electoral campaigns will need to be funded, judges risk being influenced by donors—especially if the funds come from Mexico’s powerful cartels. The reforms will also create an elected disciplinary tribunal with the power to punish judges who deviate from a partisan interpretation of the law.

Having rammed the judicial reforms through the legislature, the Morena Party is now considering other constitutional reforms. On 21 November, Mexico’s lower house approved a measure to abolish a series of autonomous bodies that regulate economic sectors and ensure governmental transparency. It seems likely that, as Polo argues, López Obrador’s de-institutionalisation agenda will result in a more corrupt and personalised political system moving forward.

On 28 July, President Nicolás Maduro held elections in Venezuela. These were the result of an international agreement reached on 17 October 2023 in Barbados, in which Caracas committed to holding free and fair elections in 2024 in return for the loosening of US sanctions, imposed in response to the democratic backsliding that has occurred under Venezuela’s chavismo regime. (Chavismo is the populist leftist ideology of former strongman Hugo Chavez and his successor Maduro). In 2017, the United States imposed financial sanctions after Maduro’s government sidelined Venezuela’s National Assembly after the opposition gained a majority there in late 2015. In 2019, oil and gold sanctions were imposed in response to electoral fraud committed during the 2018 presidential elections and to the failure to recognise opposition leader Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s rightful president.

These sanctions exacerbated the already severe economic crisis that engulfed the country during the final years of the Chavez government and has continued under Maduro. Decades of economic mismanagement and rampant corruption led to inflation rates of 1 million percent by August 2017, while GDP dropped from USD$115 billion in 2017 to $43.9 billion in 2024. By some estimates, over 90 percent of the population now lives in poverty, while more than 7.7 million have fled to neighbouring states such as Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, and Peru.

Under the Barbados agreement, the chavismo regime had committed to holding free and fair elections—but they reneged on the agreement. The pro-government Supreme Court disqualified the leading opposition candidate Maria Corina Machado, while government forces arrested more than 70 members of her team and detained over 100 others. Machado and the opposition then threw their support behind mild-mannered 74-year-old retired diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia. In the months leading up to the polls, the government continued to subject the opposition to harassment. The country’s highest-profile human rights advocate, Rocío San Miguel, was imprisoned, alongside several campaign workers.

On election day, Venezuelans turned out en masse to exercise their right to vote. At midnight on 29 July, Venezuela’s electoral commission declared Maduro the victor, with 51 percent to González’s 44 percent. But the commission never provided the actual tallies required—claiming that they had been the victims of a hacker attack. The opposition managed to publish 83 percent of the electoral records, which indicated that González had won. Their findings have been verified by independent election experts. International responses have been mixed. Democratic countries like Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, the UK, the US, and the EU states have refused to recognise the results without evidence; autocratic regimes such as China, Cuba, Iran, Nicaragua, Russia, and Syria have been quick to congratulate Maduro on his victory.

The electoral cover-up has provoked spontaneous protests across the country, especially in the poorer neighbourhoods of the big cities. The state responded with repressive measures: more than 1,600 people were arrested and 30 died over the course of the following month. According to Human Rights Watch, hundreds of anti-government protestors have been charged with crimes like terrorism, incitement to hatred, and resistance to authority. In September, González fled to Spain to escape an arrest warrant. He has since claimed that he was coerced into signing a letter declaring Maduro the election winner. Machado also remains in hiding, probably in Venezuela.

Common Trends

The elections that have taken place this year have a few factors in common.

First, institutions—whether judiciaries, auditing agencies, or legislatures—have proved crucial to ensuring democratic resilience. Faye’s victory in Senegal would have been impossible had the Constitutional Court not blocked former president Sall’s attempts to postpone the elections. In Namibia, the Financial Intelligence Centre’s discovery of a $650USD million bribery scandal involving Namibian politicians is believed to have led to the ruling party SWAPO’s significant losses in the 2019, 2020, and 2024 elections. The elections in Botswana and Somaliland were both won by opposition candidates thanks to the fact that those countries’ institutions were able to support the changing needs of voters.

In Mexico and Indonesia, however, there are causes for pessimism. Both countries’ elections were preceded by years of institutional erosion and the concentration of power in the executive. Voters prioritised economic concerns over the long-term health of their institutions. Pakistan and Venezuela, on the other hand, provide some hope. Despite exercising overwhelming control over the state apparatus, both the Pakistani military and the Maduro regime suffered rebukes from voters, thanks to well-organised opposition factions.

Second, thanks to the developing world’s relatively youthful demographics, young voters played a crucial role in electoral outcomes. For many of them, the state’s ability to create enough respectable jobs is the make-or-break factor when it comes to casting a vote. In places like India and Pakistan, high youth unemployment and sluggish job creation have led many younger voters to turn against the status quo and vote against incumbents. In Botswana and South Africa, young voters turned away from the Former Liberation Movements, lacking the nostalgia for the liberation struggle that often influences their elders. Instead, many now prioritise good governance and the delivery of state services. The lack of historical perspective among the young, however, can be a double-edged sword. Prabowo’s sweeping victory in Indonesia was fuelled by young Indonesians with no memories of the dictatorial days of Suharto’s New Order regime.

Ultimately, what the Year of Elections should teach us above all is that democracy is not something to be taken for granted; it must be constantly nourished and protected. Even in the old democracies of the West, there has been a noticeable decline in liberal democratic norms. The re-election of Donald Trump, the post-Brexit chaos in the UK, and the ongoing gains made by the far Right in continental Europe, all tarnish the image of the West as a liberal role model to emulate. After the 6 January 2021 insurrection in the US, the riots that broke out across the UK this summer, and the attempted assassination of Donald Trump in July, even political violence can no longer be seen as solely the domain of less developed countries.

Democracy should no longer be viewed as a system that the West has perfected—and which the Rest are belatedly learning, guided by the West. Instead, we should regard all countries as facing the same challenges to democracy—albeit to varying degrees. The factors that undermine democratic resilience—corruption, populism, polarisation, misinformation, inequality, economic stagnation, ethnic tensions, and institutional erosion—affect both the consolidated democracies of the developed world and the competitive authoritarian states of the developing world. We must work together to tackle these issues.