Art and Culture

The Eerie Beauty of ‘Flow’

Gints Zilbalodis’s beautiful dystopian story feels like the start of a new era in cinema, or at least the invitation to one.

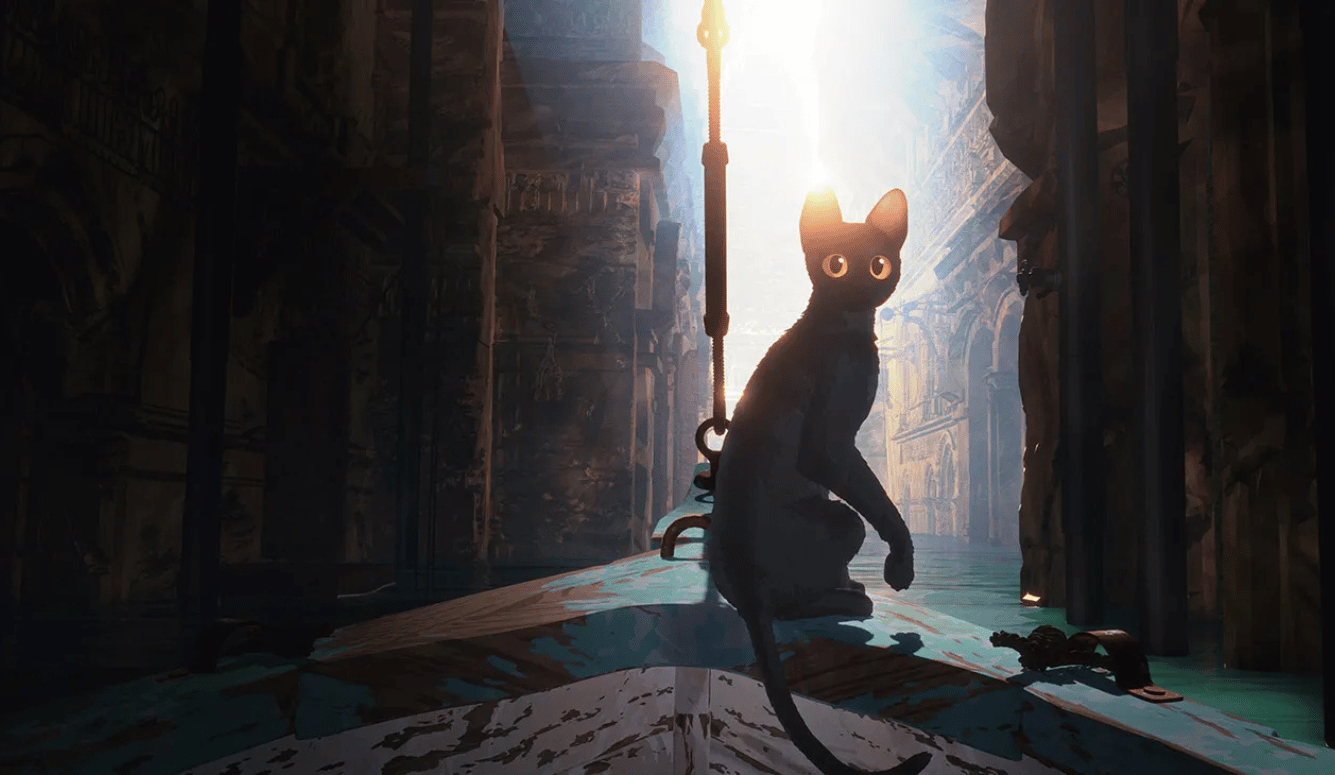

On the surface, Gints Zilbalodis’s Flow is simple enough that even a toddler can enjoy it. The plot and stakes are lessons in ruthless efficiency. A lonesome cat—named Flow in promotional material—has to survive on a small boat when a flood surges across the Earth. As the film progresses, the boat’s “crew” comes to include a capybara, a lemur, a secretary bird, and a golden retriever. Naturally, the animals’ coexistence is far from easy, and the line between cooperation and eating each other is sometimes blurry.

One of the most striking aspects of Flow is how Zilbalodis has chosen to tell his story. There is no dialogue—not even a narrator—and there are no people. This is a story about real animals and how they might plausibly behave after humanity’s extinction. All their thoughts are conveyed through meows, barks, whimpers, and body language—a self-imposed constraint that forces the movie to show, not tell. No words are exchanged between the lemur and secretary bird as they feud over access to the rudder in one pivotal scene, but the bird’s opinion of its crewmate is obvious when it kicks the lemur’s prized glass orb into the sea.