Israel

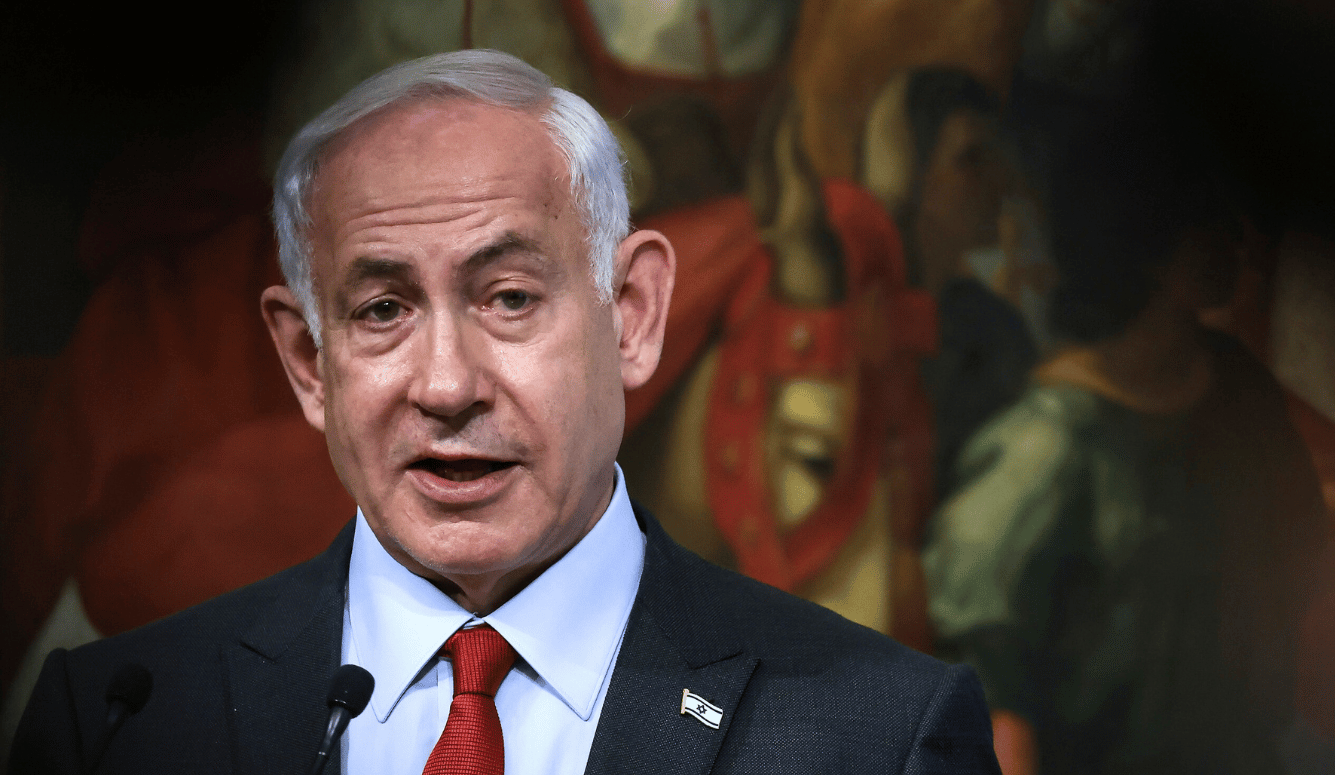

Benjamin Netanyahu, Would-Be Authoritarian

Amid the fog of war, Netanyahu has been pushing ahead with his highly unpopular “judicial reforms,” which would concentrate power in his hands and allow him to undermine free speech and the rule of law in Israel.

Last Wednesday, 20 November, Israel’s leading daily, Haaretz, ran a full-length advertisement on its front page—a highly unusual occurrence. The ad featured a photo of the country’s attorney-general, Gali Baharav-Miara, and was captioned “Continue to uphold the rule of law on behalf of all of us.” It was signed by the “Business Forum,” which consists of the heads of Israel’s 200 leading corporations, including the country’s major banks and insurance, pharmaceutical, technological, and energy companies.

Israel’s business leaders—along with the Israel Bar Association and most of the country’s journalists, academics, and intelligentsia—support Baharav-Miara, against whom Netanyahu and his cabinet have mounted a public campaign with the probable aim of forcing her resignation, or as a prelude to firing her. She has been vilified by cabinet ministers as an “anarchist” and “the most dangerous person to the State of Israel.”

So far, Baharav-Miara has braved the storm and continues to oppose government actions that she believes are designed to weaken or destroy Israel’s democratic infrastructure and the rule of law. But the government appears bent on replacing her with a yes-man or -woman, much as, last month, Netanyahu fired Defence Minister Yoav Gallant and replaced him with the compliant—though inexperienced and inept—Likud Party apparatchik, Yisrael Katz. Gallant was dismissed because he opposed Netanyahu’s efforts to get the Knesset to pass a law legitimising the continued exemption of the country’s ultra-Orthodox community—who comprise some 15 percent of Israel’s population—from military service.

The military service exemption was first introduced by Israel’s founding prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, during the state’s first decade, when the ultra-Orthodox constituted only 1–2 percent of the population. But in 1977, Menachem Begin, the country’s first right-wing prime minister, made the exemption permanent. The IDF is currently engaged in a war on several fronts: it needs every hand on deck. Israeli Jews now overwhelmingly support conscription for the ultra-Orthodox, but Prime Minister Netanyahu remains opposed, since he needs the cooperation of the two ultra-Orthodox political parties, Shas and United Torah Judaism, with their combined 18 Knesset seats, to maintain his coalition.