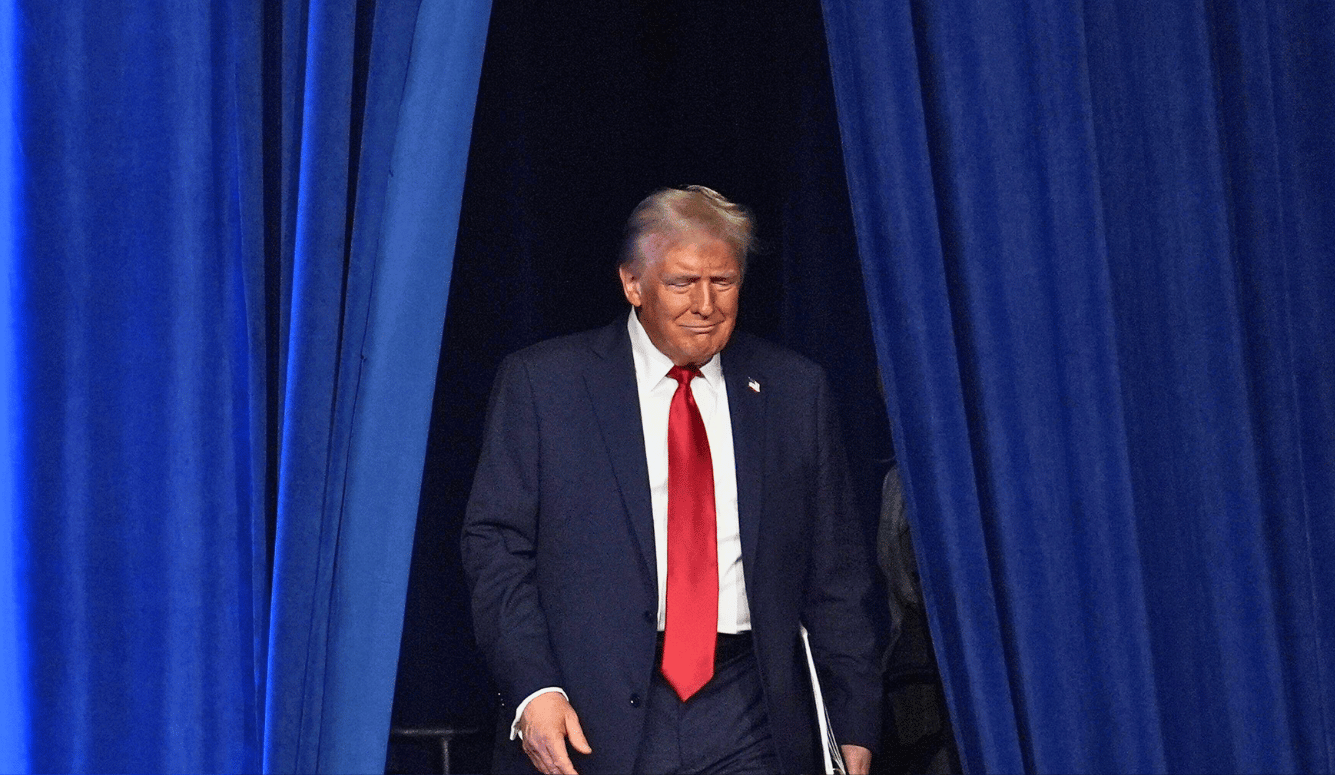

Politics

Europe Awaits Trump II

The president-elect’s arrival in the White House will likely galvanise the European New Right and doom the Ukrainian resistance.

A few hours after Donald Trump’s re-election as US president was confirmed, the former Democratic presidential candidate and governor of Vermont, Howard Dean, argued that the result would force Europe to grow up. “No question,” he told the BBC’s World at One, “Europe has to learn to stand on its own. The day of the United States setting the tone, especially in defence, is gone. This will put an enormous stress on the EU. The US is no longer going to be reliable to deal with Ukraine, with Russia. ... [Trump] has a close relationship with President Putin, and he will get what he wants.”

But demanding that European states, within and outside the European Union, stand on their own feet ignores how comfortable those feet have become in their slippers since the beginning of the Cold War. So named by George Orwell in 1945 (a great-power stand-off was the inspiration for Nineteen Eighty-Four), the Cold War became a reality by 1947–48 as the Soviet Union imposed its control over Central Europe and the US Marshall Plan pumped money into Western Europe to regenerate its economies. In spite of hostility to anti-communist ideology on the part of the European far-left, the mechanisms of deterrence were upheld by centre-right and centre-left governments throughout the Cold War, normalising the leadership of the US and the deployment of tens of thousands of American troops in Europe and elsewhere. Under unchallenged American leadership, Europe benefited greatly, and especially economically, from the protection of the US security umbrella.

The Pax Americana also provided shelter for the development of the European Union from its fledgling bureaucratic life in the Council of Europe (1949) and the European Coal and Steel Community (1952). The US liked the idea of a united Europe, believing it would give successive administrations a central authority with which to discuss and propose things. Europe and the US have remained close allies ever since, although that central authority never appeared. Henry Kissinger’s apocryphal query, “Who do I call if I want to speak to Europe?” seemed to have been answered in 2009 when the EU appointed a high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, which provided the US with a point of contact. However, successive high representatives have been permitted little authority over EU members’ foreign policies.