Art and Culture

Blonde on Blonde

Andrew Dominik’s much-maligned film about the life and death of a screen icon claws through the sentimental myth-making in search of terrible truths.

I.

In September 2022, Netflix released Blonde, Andrew Dominik’s 167-minute adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’s 738-page novel about the life and death of Marilyn Monroe. If the studio’s executives expected the film to be greeted with plaudits and awards, they were mistaken—most critics responded with scorching outrage to Dominik’s brutal and lugubrious take on the misfortunes of the screen icon and sex goddess who died following a self-administered overdose of Nembutal some sixty years before. Her death was officially ruled a suicide, but alternative theories still abound.

“‘Blonde’ abuses and exploits Marilyn Monroe all over again, the way so many men did over the cultural icon’s tragic, too-short life. Maybe that’s the point, but it creates a maddening paradox: condemning the cruelty the superstar endured until her death at 36 while also reveling in it.” That was Christy Lemire, who gave the movie two and a half stars on the Roger Ebert website, while delivering only grudging praise for the performance by Cuban-Spanish actress Ana de Armas in the title role. Writing for NPR, Justin Chang pronounced, “The movie turns Monroe into an avatar of suffering, brought low by a miserable childhood, a father she never knew and an industry full of men who abused and exploited her until her death in 1962, at the age of 36. There’s truth to that story, of course, but it’s hardly the only truth that can be drawn from Monroe’s tough life and extraordinary career.”

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times had this to say:

All that’s missing from this portrait is, well, everything else, including Monroe’s personality and inner life, her intelligence, her wit and savvy and tenacity; her interest in—and knowledge of—politics; the work that she put in as an actress and the true depth of her professional ambitions. (As Anthony Summers points out in his book “Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe,” she formed her own corporation: Marilyn Monroe Productions, Inc.) Mostly, what’s missing is any sense of what made Monroe more than just another beautiful woman in Hollywood: her genius. Watching “Blonde,” I wondered if Dominik had ever actually watched a Marilyn Monroe film, had seen the transcendent talent, the brilliant comic timing, the phrasing, gestures and grace?

Then there was the New Yorker’s Richard Brody: “The movie is ridiculously vulgar—the story of Monroe as if it were channelled through Mel Gibson’s ‘The Passion of the Christ.’” Having one’s film compared to The Passion of the Christ is perhaps the most withering criticism a director can endure, but Brody wasn’t finished. Deeming Blonde an exercise in “cheap sentiment, brazen tastelessness, and sexual exploitation,” he went on to echo Dargis:

There’s nothing of her effort to escape from poverty and drudgery, her serious and thoughtful efforts to develop her career; not a word about Monroe’s extremely hard work as an actress, or her obsessive dependence, for seven or eight years, on her acting coach Natasha Lytess. In short, whatever has to do with Monroe’s devotion to her art and her attention to her business is relegated to the thinnest of margins.

Blonde came in for particularly scathing criticism from abortion-rights activists. In Dominik’s movie, generally following Oates’s storyline, Monroe has two abortions: her first, at the age of 26, is arranged by her studio so that she could play the shapely gold-digger Lorelei Lee in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953); the second is forced on her by Washington operatives because she is carrying the love child (if it can be called that) of John F. Kennedy. (The real-life Marilyn Monroe was not known to have had any abortions—and whether she even slept with JFK, and later, his brother Robert, as many believe, is still a matter of conjecture. Yet she did apparently have a supersaturated love life, and illegal but easily obtainable D&C procedures by black-market physicians were far from uncommon amid the mid-century Hollywood overpopulation of ambitious young actresses with only a handful of years to turn themselves into stars.)

Dominik portrays both abortions as nightmares; the imagery is so phantasmagoric that I wondered if they weren’t simply the byproduct of anaesthesia-induced hallucination. “For this you killed your baby,” Blonde’s Marilyn mutters forlornly from her audience-seat at Gentlemen's gala premiere as she watches herself on the screen clad in skin-hugging pink satin and warbling in her infantile whisper: “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend.” Abortion-rights people didn’t like that at all.

They were even less impressed by the conversations that Dominik’s Marilyn has during subsequent pregnancies with her unborn children—computer-generated intra-uterine foetal images reminiscent of Lennart Nilsson’s famous 1965 photographs in Life magazine. These apparitions first appear during Marilyn’s first aborted pregnancy, the consequence of an affair she was supposed to have had with Charles “Cass” Chaplin Jr. (Xavier Samuel), the legendary actor’s son. They reappear during a pregnancy with her third husband, Arthur Miller (Adrien Brody), which she ultimately miscarries. (The real-life Monroe was married to the playwright from 1956 to 1961, and suffered at least two miscarriages before their divorce.)

Speaking to the Hollywood Reporter, Planned Parenthood spokeswoman Caren Spruch complained that Dominik’s film contributed to “abortion stigma,” via “a CGI-talking fetus, depicted to look like a fully formed baby.” In fact, the image looks strikingly like Nilsson’s full-colour cover portrait of a foetus at eighteen weeks, sleeping inside the amniotic sac. No matter—Richard Brody called the scenes Dominik’s “fetus follies.” Vanity Fair’s Carey Purcell called Blonde a “pro-life fever dream.” It was not a compliment.

There was a reason for this nearly uniform show of critical hostility, and it didn’t simply rest on Dominik’s politically incorrect take on pregnancy termination. Blonde is a movie that violates—or more accurately, bears only an asymptotic relationship to—all previous narratives of Marilyn Monroe’s life. This includes what can be gleaned of Monroe’s actual biography from beneath the growing mountain of hyperbole. Since her death on 4 August 1962, at least three-dozen book-length biographies have been published, plus innumerable memoirs and photograph collections and an ostensible 1974 autobiography titled My Story (actually ghostwritten by Ben Hecht). Contra what Justin Chang and Manohla Dargis seem to think, Blonde does not even claim to be a biopic with an obligation to do justice to its subject’s “tough life” or “intelligence” or business “savvy” (although there is plenty of all three in Dominik’s movie).

Indeed, Blonde does not even purport to be faithful to Oates’s 2002 novel, which Oates herself characterised in her own foreword as a “radically distilled” version of Monroe’s life, with “synecdoche” as its guiding principle. For example, Oates has young Norma Jeane living in only a single foster home (“and that’s fictitious”) after she is abandoned by her mother, instead of the dozen in which she actually resided. “[I]n place of numerous lovers, medical crises, abortions and suicide attempts, Blonde explores only a selected few,” Oates writes. This simplification provided Oates with a melodramatic plot that culminates in Monroe’s murder by a CIA “Sharpshooter” dispatched by the Kennedys to administer a lethal injection of Nembutal. (Of course the Sharpshooter, who haunts other episodes in Monroe’s life as Oates narrates it, may also be a figure of the troubled heroine’s imagination.) “Biographical facts regarding Marilyn Monroe,” Oates warns her readers, “should be sought not in Blonde, which is not intended as a historic document, but in biographies of the subject.” Oates ad-libs poems, diary entries, and scraps of media interviews into her novel, all of which are Oates’s own inventions.

Dominik wrote the screenplay for Blonde himself, and obviously used Oates’s novel as a template. But he also wrought drastic changes to its ambience and plot (there is no Kennedy-ordered execution, for example), and these changes—to an already heavily fictionalised novel—are so significant that complaints about historical accuracy seem absurd. No review of the movie that I have read, however, has mentioned these alterations—probably because no reviewer, much less anyone else, has actually managed to slog through all of Oates’s jungle-dense, overwritten door-stop (738 oversized and narrow-margined pages housing dialogue-free paragraphs of Faulknerian length that cover the paper like area rugs).

The only reviewer I’ve encountered who seemed to understand what Dominik might be up to was Mark Kermode in the Guardian, who noted that Monroe’s suffering in Blonde might be more attributable to principalities and powers than to the machinations of male-dominated Hollywood determined to suffocate her alleged genius. “Blonde is a horror movie masquerading as a film about fame,” Kermode observed, and he compared the scenes in which abortion doctors in bloated surgical gowns and face-masks loom over her parted thighs to the womb-perspective birth scenes in Rosemary’s Baby. “I would argue that in the end Blonde isn’t really about Marilyn at all. It just happens to be wearing her wardrobe,” he concluded.

Blonde doesn’t really fit into the tradition of troubled-star biopics like Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis (2022) or Martin Scorsese's The Aviator (2006) or Gordon Douglas’s Harlow (1965), in which Monroe had originally been slated to play the 1930s doomed actress in the title role. It more closely resembles films like William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), and particularly, Robert Eggers’s The Witch (2015), in which a beautiful and innocent young girl is cast out by her fanatical family and becomes a slave of Bahomet in return for pretty dresses and promises of sexual ecstasy. As Kermode wrote, Blonde is a Faustian tale in which fervently sought celebrity is an agent of personal destruction. But it is also about something more: human powerlessness in the face of calamitous and diabolical forces beyond any semblance of personal control. And in Blonde, those forces revolve around genetics and genealogy, maternity and paternity, birth and non-birth. The movie’s central theme is the generational curse—but a generational curse with distinctive and distinctively demonic human agents.

II.

The prevailing narrative about the life of Marilyn Monroe took shape shortly after her apparent suicide and was almost fully formed by the end of the 1960s. It was then enhanced during the 1970s, when second-wave feminists began to argue that Monroe had been a serious artist crushed by Hollywood misogyny.

Nearly every biography of Monroe draws on this mythology, even Donald Spoto’s presumably definitive Marilyn Monroe: The Biography (1999), which purports to debunk much of the JFK connection with the claim that she probably slept with him just once (once!). Hollywood biographer Fred Lawrence Guiles’s Norma Jean: The Life of Marilyn Monroe (1969) created the template that survives to this day regarding the star’s brief and troubled existence (Guiles’s variant spelling of her birth name, Norma Jeane Mortenson, was fairly common during the 1960s.) In 1991, Guiles repackaged Norma Jean as Legend: The Life and Death of Marilyn Monroe.

The central psychological fact of Marilyn Monroe’s life was that she never knew who her father was. This had a core of truth—the surname “Mortenson” on her birth certificate belonged to the man to whom her mother, Gladys Baker (née Monroe, interestingly enough, and rivetingly portrayed by Julianne Nicholson in Dominik’s movie), was briefly married at the time of her daughter’s birth in Los Angeles in 1926. Young Norma Jeane usually went by the surname “Baker,” after Gladys’s first husband (who had absconded to Kentucky with Norma Jeane’s two older half-siblings), until she legally changed her name to Marilyn Monroe in 1956.

Gladys died in 1984, surviving her daughter by 22 years. She was mentally unstable—paranoid schizophrenia was the official diagnosis, probably inherited from her own mentally ill and alcoholic father—and Norma Jeane spent most of her childhood from the age of two weeks in a dozen foster homes and a Los Angeles County-run orphanage. She lived with her mother only briefly during 1933–4, before Gladys suffered yet another mental breakdown and was institutionalised in state and private hospitals off and on for most of the rest of her life. So, Norma Jeane was abandoned as much by her maternal parent as her paternal one. As an adult, she told reporters stories that might well have been true but were impossible to verify: that someone had tried to strangle her in her crib when she was thirteen months old, and that she had been raped in at least one of her foster homes.

Gladys was a strikingly attractive woman. A photo of her from the early 1930s (inferable from her dress style) shows an uncanny resemblance to her daughter: a less busty Marilyn without makeup and with unruly curls unstyled by a hair salon. She had worked, when she was able to work, as a negative-cutter for a Hollywood film-processing company, Consolidated Film Industries, and later for RKO Pictures. DNA tests released in 2022 revealed that Monroe’s biological father had been Charles Stanley Gifford (1898–1965), a good-looking co-worker of Gladys’s at Consolidated, who, with pencil moustache and rakish fedora, bore a startling resemblance to Clark Gable.

Monroe, by most accounts, knew all about her Gifford ancestry (obviously learned from her mother) and tried in vain on several occasions to persuade the twice-married Gifford to acknowledge her as his daughter. But she was said to have told schoolmates that Gable was her father, a datum that must have seemed odd when she made her last completed movie, The Misfits (1961), with him. At twenty years her senior, he played her ageing-cowboy lover (and died of a heart attack shortly after filming wrapped in 1960).

This true story of a neglected child marked by paternal indifference, maternal mental illness, and (possible) childhood sexual abuse is a sad one, but it also became an easy trope: Marilyn Monroe’s “daddy issues.” Her unusual dependence on Hollywood men who turned her into a sex symbol was supposedly evidence of this. As was her choice of paternalistic second and third husbands: Joe DiMaggio (to whom she was married for nine months in 1954) and Miller, even though both men were actually only 12 years and 11 years older than her, respectively.

And so, Monroe’s yearning for her absent father became part of her mythology. She also yearned to be taken seriously as a bona fide actress, not just a charming blonde—hence her attachment from 1955 to Lee Strasberg, godfather of 1950s Method Acting. Strasberg’s wife, Paula Strasberg, even accompanied her to the set for every shoot, demanding retakes when she deemed Monroe’s performance inadequate. This was promptly translated by Monroe’s admirers into assertions that she was in fact a serious actress, her high intelligence and prodigious latent talent ruthlessly muffled by the Hollywood studio system that insisted on typecasting her as a vacuous sexpot.

Already weighed down by malign genetics, let down by the men she loved, and systematically stymied in her career (or so she believed), Monroe sank into alcohol- and drug-dependency (vodka, tranquillisers, the 1960s pop-opioid Demerol, and “Valley of the Dolls” barbiturates combined with Dexedrine to jolt her into alertness, most of which was apparently supplied by the psychoanalyst she was by then seeing daily). Consequently, her behaviour became increasingly erratic and unprofessional—she was habitually late to shoots, failed to memorise her lines, and threw emotional tantrums on set. In the spring of 1962, her longtime studio, 20th Century Fox, fired her from the uncompleted remake of screwball comedy Something’s Got to Give, in which she was supposed to have co-starred with Dean Martin.

This postmortem hagiography went full-blown in 1973, when Norman Mailer wrote a verbose 100,000-word introduction to a coffee-table collection of more than a hundred oversize photographs titled Marilyn Monroe: A Biography. Here is a sample of Mailer's rococo prose:

No force from outside, nor any pain, has finally proved stronger than her power to weigh down upon herself. If she has possibly been strangled once, then suffocated again in the life of the orphanage, and lived to be stifled by the studio and choked by the rages of marriage, she has kept in reaction a total control over her life, which is perhaps to say that she chooses to be in control of her death, and out there somewhere in the attractions of that eternity she has heard singing in her ears from childhood, she takes the leap to leave the pain of one deadened soul for the hope of life in another, she says good-bye to that world she conquered and could not use.

That same year, as if to outdo Mailer in Marilynolatry, Elton John released one of his most famous songs, “Candle in the Wind”:

Goodbye Norma Jeane

Though I never knew you at all

You had the grace to hold yourself

While those around you crawled

They crawled out of the woodwork

And they whispered into your brain

They set you on the treadmill

And they made you change your name

And it seems to me you lived your life

Like a candle in the wind

Never knowing who to cling to

When the rain set in....

It was a hauntingly beautiful piece of music, composed at the very height of John’s most creative period during the early 1970s. By then, Monroe already had her own religious iconography, in the multiple silkscreen prints that Andy Warhol had made from a photograph of her in 1962 and 1967. “Candle in the Wind” became her Te Deum.

Meanwhile, brand-new second-wave feminism arrived to contend that Marilyn Monroe hadn’t simply been a victim of the studio system’s stereotype-fuelled miscasting, she was a victim of male-gaze misogyny as well. In a 1972 article for Ms. magazine titled “Marilyn Monroe: The Woman Who Died Too Soon,” Gloria Steinem wrote:

She was a student ... a pupil of Lee Strasberg, leader of the Actor’s Studio and American guru of the Stanislavski method, but her status as a movie star and sex symbol seemed to keep her from being taken seriously even there. She was allowed to observe, but not to do scenes...

Yet she was forced always to depend for her security on the goodwill and recognition of men; even to be interpreted by them in writing because she feared that sexual competition made women dislike her. Even if they had wanted to, the women in her life did not have the power to protect her. In films, photographs, and books, even after her death as well as before, she has been mainly seen through men’s eyes.

Steinem’s feminist leitmotif, later incorporated into a full-length book, Marilyn: Norma Jeane (1986), has woven itself into nearly every subsequent take on the actress. In a heavily footnoted 535-page biography, Marilyn: The Passion and the Paradox (2013), Lois Banner, a now-retired professor of history and gender studies at the University of Southern California, added a twist: Monroe’s very position as a “sex symbol” (to use Steinem’s phrase) was a platform of feminist rebellion against the very misogyny that sought to objectify her:

I dismissed Marilyn as a sex object for men. By the 1990s, however, a generation of third wave feminists contended that sexualizing women was liberating, not demeaning. … Was she a precursor of 1960s feminism? Was there power in her stance as a sex object?

Banner’s book is perhaps the longest and most macabre of all Marilyn Monroe biographies. It portrayed young Norma Jeane's childhood as oscillating between multiple episodes of sexual abuse starting at age eight (to reiterate, there is little actual evidence that this occurred, although it could have) and hellfire terror of her sexuality, allegedly induced by her evangelical foster parents in the longest-lasting of her foster domiciles (Banner had been raised evangelical-Christian herself so she could relate).

“[N]o other film star endured a childhood so traumatic,” Banner wrote. “[T]he sexual abuse she had endured as a child had programmed her to please men.” A combination of “childhood trauma” and the “male gaze” was what caused Monroe’s deterioration into unprofessional conduct as time passed. It was, according to Banner, a kind of private rebellion against the studio heads and directors who personified the masculine abuse she had been forced to endure for most of her thirty-plus years. Banner also claimed that “significant among my discoveries about Marilyn are her lesbian inclinations. ... No other biographer has addressed her bisexuality.”

As for Monroe’s death, Banner speculated that it might have been homicide (a drug-laced enema?), arranged by a Kennedy to put a stop to the increasingly embarrassing rumours about her involvement with the two brothers. (August 1962 was only a few months after Monroe had famously sung a bleary “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” during a celebration at which Jackie Kennedy was conspicuously absent.) Alternatively, Banner theorised, “Marilyn killed herself because she couldn’t handle her lesbian urges.”

III.

Joyce Carol Oates’s Blonde preceded Banner’s biography by twenty years, but it is very much in the same vein. “Men ruled Hollywood, and men must be placated,” Oates has Norma Jeane reflect during an apparently mandatory assignation with “W” (Oates’s tag for Richard Widmark, Monroe’s co-star in her 1952 movie Don’t Bother to Knock). “This was not a profound truth. This was a banal and thus a reliable truth.”

But what if Marilyn Monroe was actually not much of an actress at all, and the notion of her as a brilliant player relentlessly stifled by male sexism was so much feminist hooey? The New Yorker’s celebrated film critic and essayist Pauline Kael believed scarcely a word of the official story. In a 1973 review of Mailer’s book for the New York Times, Kael hinted that Monroe’s tales of childhood sexual mistreatment and obsession with finding her father were likely fabrications, the sole source of which was Monroe’s own interviews during the mid-1950s, decades after these episodes were alleged to have taken place.

Kael had a point. Much of the purported information we have about Marilyn Monroe’s abuse-laden early life is uncorroborated data offered by Monroe in conversations with journalists at the height of her fame, most luridly in a 1956 Time magazine cover story. Although Time maintained that a team of 34 reporters contributed more than 100 interviews to the story, it now seems clear that Monroe’s tales of her childhood verged on the fantastical: the abusive fundamentalist foster parents who beat her with “a razor strop,” forced her to scrub floors as a toddler, and took her to church three times every Sunday, and the Dickensian orphanage where she earned five cents a month washing more than a hundred dirty dishes after each meal.

Kael speculated that Monroe had bamboozled the press, “embroidering that raped and abused Little Nell legend that Time sent out to the world in a cover story.” Far from being an actress of stunning talent misused by the studios, Kael maintained that Monroe had no acting talent whatsoever:

[A] good case could be made for her as the first of the Warhol superstars (funky caricatures of sexpot glamour, impersonators of stars). Jean Harlow with that voice of tin may have beat her to it, but it was Monroe who used her lack of an actress’s skills to amuse the public. She had the wit or crassness or desperation to turn cheesecake into acting—and vice versa. ... She would bat her Bambi eyelashes, lick her messy suggestive open mouth, wiggle that pert and tempting bottom, and use her hushed voice to caress us with dizzying innuendos.

In the Time cover story, Monroe had expressed a lifelong desire to play Grushenka in a film version of The Brothers Karamazov. Kael scoffed that the idea of Marilyn Monroe starring in a period picture of any kind was laughable.

In a review of Lois Banner’s Monroe biography for the Atlantic, Caitlin Flanagan echoed some of Kael’s sentiments. Flanagan theorised that Monroe, suicidal or not, had died just in time, before the counterculture revolution of the late 1960s rendered blonde bombshells in stilettos obsolete:

The next few years made a mockery of women like her, banishing them to television variety shows and gag roles: the bottle blonde with the chinchilla stole and the sugar daddy, stuck like a La Brea Tar Pit mammoth in the hardening pastel Bakelite of ’50s populuxe. Only a veterinary-level dose of barbiturates stood between Marilyn and a second callback for Eva Gabor’s role on Green Acres. Maybe she even saw it coming: “Please don’t make me a joke,” she is supposed to have said, not long before the end.

There is something to be said for all this. At the end of her life, Marilyn Monroe was on the downward slope of the decade that leads to forty and her face was already displaying the flaccid ravages of drug and alcohol over-consumption. She looked terrible in her last movie (although it didn’t help that she had been put into a stiffly styled blonde wig to save having to have her hair redone for every take in the windy Nevada desert). The video of her “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” is cringe-inducing.

And her “serious” filmography isn’t much. The Misfits was a flop Marxist morality play, scripted by Arthur Miller, about eat-the-poor capitalism Wild West-style. Bus Stop (1956) was the incoherent handiwork of heartlands playwright William Inge, with a heavy-handed comic plot involving a blowhard rodeo cowboy (Don Murray) and a talentless nightclub singer (Monroe). It was also one of the two movies she made with her short-lived production company. The other was The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), another flop (although fairly popular in the UK, since it co-starred Laurence Olivier).

Flanagan identified only one redeeming role in all of Monroe's 23-film oeuvre: Billy Wilder’s wonderful (although now politically incorrect, what with its drag sendups) classic Some Like It Hot (1959): “a perfect script, co-stars who were better than she was, a role that let her play dumb without in any way giving a dumb performance.” I would add another: Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955), the film with the billowing dress over the subway grate. In that movie she demonstrated what she could demonstrate best, and why it was impossible for men not to fall in love with her and to forgive her anything: a pure innocence in her frank enjoyment of her own carnality.

She could kiss a man (costar Tom Ewell) in a completely artless fashion, simply to bestow pleasure; she could camp out in his apartment only—yes, only—so she could cool herself with his air-conditioning during the stifling Manhattan summer; she could persuade him wordlessly and unthinkingly that it would be a mistake for him to betray his wife with her because that would ruin everything. That sweetness, coexisting comfortably alongside the slathered-on sexiness—of course she loved babies and children and dogs—was what people identified immediately and cared for intensely. It was what differentiated her from other Hollywood blondes—Jayne Mansfield, Diana Dors—who were merely busty glamour queens.

As for what the real Marilyn Monroe was like, I have no idea. Her family on both sides hailed from the vast Midwestern (and Southeastern and Southwestern) migration to the dusty and underpopulated flatlands of Southern California during the early 20th century, memorialised in novels like Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust and John Fante’s Ask the Dust (both 1939). My husband’s family was part of that migration on both sides. He grew up in Hawthorne, a working-class town south of Los Angeles where Monroe’s mother had lived when Norma Jeane was born. The evangelical couple about whom Monroe complained to Time, Albert and Ida Bolender, were, in fact, Gladys’s Hawthorne neighbours and friends. She had handed off her two-week-old infant to them and left her there until she scooped her up again at the age of seven, visiting only occasionally (the Bolenders attended Norma Jeane’s first wedding; Gladys was hospitalised and could not attend).

When I read Monroe's description in Time of Hawthorne as a “semi-rural semi-slum,” I knew she had embellished her recollections. Hawthorne was semi-rural in the sense that some residents kept chickens and occasional cows and hogs in their unusually large back yards (land was cheap), but it was mostly modest but tidy bungalows, small retail businesses, and the Lions Club. My husband’s maternal grandfather was the city clerk during the 1930s and a respectable figure. Many residents made their living, as Gladys did, in the workaday support periphery of “the Industry,” commuting up La Cienega Boulevard to the lights and glamour. One of my husband’s great-aunts had been Douglas Fairbanks’s hair-stylist.

Marilyn Monroe certainly had a spectacular body—so spectacular that even as a teenager she was voted “Miss Oomph” by her high-school classmates in 1941. Her figure has been described as an “extreme hourglass”—a tiny waist (22 to 24 inches in her recorded measurements) that made the rest of her look voluptuous. It helped that somewhere in the modelling classes she took as a seventeen-year-old she learned to lean forward into the camera to display her breasts. But her greatest asset was her face: not conventionally beautiful but pretty enough, and so expressive in its eagerness to be seen and admired that it’s the first thing you notice in photos of her, even the famous nude shots that showed up in the premiere issue of Playboy. You can’t take your eyes off that face. It loved the camera, and the camera loved it back. You can see that mutual adoration—and her trademark glossy smile already abloom with layers of lipstick—in her first-wedding photo, taken in 1942 when she was just sixteen.

In Oates’s novel, where all the males are leering grotesques of one sort or other, her first husband is portrayed as an oafish semi-perv who introduces her to posing nude by taking pornographic pictures of her and showing them off to his work pals. In real-life, Monroe’s first husband, James Dougherty (Oates mercifully changed his name when she fictionalised him), actually seemed to be a decent fellow, although he and his young wife were obviously mismatched. He later built a successful career as a Los Angeles police detective and police-academy instructor. Monroe, meanwhile, was “discovered” a year after their wedding, when Dougherty joined the United States Merchant Marine and was shipped to the Pacific, and she got a Rosie the Riveter job at a munitions factory in Burbank. An Army photographer snapped her on the job for a Yank magazine feature on women in the war effort. Then, impressed by her figure and photogeneity, he came back for more. Soon enough, she was signing up at a Hollywood modelling agency and doing magazine and calendar pin-ups all over Los Angeles. Movie bit-parts were next.

Monroe was clearly not stupid, although it is difficult to say whether her much-publicised highbrow activity—taking an extension class in literature at UCLA in 1951, talking to Time about playing Grushenka (or Natasha in The Three Sisters in Andrew Dominik’s movie), or compiling an impressive personal library of literary and philosophical classics and classical-music records—reflected her genuine tastes or merely her aspirations. In a famous 1955 photo of Monroe in a striped bathing suit poring over a copy of Ulysses, does the fact that the book is opened to the very end mean that she is reading Molly Bloom’s soliloquy, or is she simply posing with the back flyleaf?

Of one thing, we can be sure. Monroe was extraordinarily dependent on other people and their approval: her husbands and lovers, the New York theatre world whose acceptance she craved as a validation of her seriousness, the acting coaches she dragged to every set, the two psychoanalysts (one on each coast) she retained for daily talk therapy, the army of physicians who supplied the multiple prescriptions for uppers and downers that she chased with vodka. She craved affirmation, and merely accumulating piles of heavy-duty books and talking about them might have reassured her that she was not a nobody who never finished high school, but someone to whom attention must be paid, like Willy Loman in her third husband’s play. It was crucial for her identity to be thought of as avant-garde.

IV.

But this pockmarked real-life narrative wasn’t enough for a feminist following that insisted Monroe was a great talent and intellect broken on the Hollywood wheel rather than a victim of her own insecurity, addictions, and dismal choices in love. Of course, Dominik’s Blonde was not the movie for them. But Joyce Carol Oates’s novel was the novel for them, and it became a bestseller upon its publication in 2002. Elaine Showalter provided a new introduction to a 2022 edition timed to coincide with the opening of the movie, in which she wrote:

[Marilyn Monroe] is the artificial creation of the Hollywood studio system, with a “sexy murmurous” name and a whispery, babyish voice. Voluptuous and seductive, her natural beauty transformed with braces, peroxide, false eyelashes, bright-red lipstick, tight clothes, and wobbly stiletto heels that make it hard for her to run away, Marilyn is all body. Yet, paradoxically, behind that glittering, glamorous image, Marilyn bears the shame and self-hatred of living in a female body in a misogynist culture—fear of being unclean; disgust with her sexuality; a lifetime of menstrual cramps, gynecological problems, miscarriages, and abortions.

This is what audiences wanted to see on the page and on the screen. Oates delivered it to them, in massive gothic chunks detailing every stick of shabby furniture in the wretched, roachy apartments she inhabited when young; every unappetising scrap of overcooked 1950s food; every unpleasant sensation and every drop of oozing, smelly byproduct from her frequent bouts of sexual intercourse; every anxiety and nightmare and woozy stomach cramp—and all of this is interspersed with pages of Joycean stream-of-consciousness, scraps of her purported poetry, bits of her purported diary rendered in arty, unreadable typography, and far too many sentences like this one. “Stinging red ants crawled inside her mouth as she lay in a paralysis of phenobarbital sleep.”

And if 738 pages of this weren’t enough (Oates is famous for her high-volume literary output, sometimes churning out two or three lengthy novels a year), Showalter reported that the original manuscript had been almost twice as long as the published book. Few of the many readers who bought Blonde (predominantly females, I am willing to bet) are likely to have got through it all. I confess that I didn’t, although I managed about 65 percent of it, skipping around to the high points.

It was Oates who invented many of the outré plot episodes that became the spine of Dominik’s movie. For example, there is no evidence that Norma Jeane’s mother tried to drown her in a bathtub as the movie relates in a variation on a plot point in Oates’s novel. The apocalyptic 1934 wildfire that sweeps through the Santa Monica Mountains is also completely fictional—although such massive conflagrations, fanned by Santa Ana winds roaring down the canyons and fuelled by the bone-dry Southern Californian underbrush at the end of summer, were and are far from uncommon. Oates’s (and Dominik’s) fictional blaze seems to have been modelled after a devastating 1933 fire that swept through Los Angeles’s Griffith Park, also in the Santa Monica Mountains, and killed at least 29 volunteer firefighters.

Darryl F. Zanuck, head of 20th Century Fox, to which Monroe was under contract for most of her career, was notorious as king of the casting couch, but there is no evidence that he (“Mr. Z” in book and movie) forced her into anal sex in his office—or had sex with her at all—as a condition of her first movie role. As a rising actress, Marilyn Monroe did date (and likely sleep with) the famous-actor scions Cass Chaplin and Edward G. “Eddy G” Robinson Jr. (Evan Williams in the movie), but not at the same time, and there is no evidence that the two men were lovers or even gay. Most significantly, the letters Monroe received over the years—supposedly from her mysterious father—never existed in real life. She always knew that Charles Gifford was her male parent, and Gifford, for his part, persisted in hanging up on the few occasions she tried to call him.

What Dominik did, I believe, was to pick through Oates’s overwrought and unwieldy novel and pull out what he thought would support a narrative of damnation. Yes, Monroe would be a victim, but not the kind of victim everyone expected. Mark Kermode correctly identified the film’s underlying theme as a “deal with the devil,” but it wasn’t the sort of explicit deal that informs, say, Rosemary’s Baby, where the actor-husband arranges for his wife to be impregnated in return for a coveted stage role. It was something more subtle and more corrosive: the demonic and fatal lure of Hollywood represents the glamour of evil. Indeed, in both novel and movie, Hollywood is simply and ominously the Studio, for which nearly all the characters work and by which they are magnetised.

In Dominik’s film, both the mother and the daughter (played as a child by a preternaturally affecting Lily Fisher) are victims. Gladys is a victim twice over— she clings to her menial job at the very edge of the stardust she hopes will be shed onto her, and then she is seduced, impregnated, and abandoned by the mysterious Clark Gable-like figure who becomes an obsession. The fire raging through the Hollywood Hills immediately recalls the apocalyptic painting “The Burning of Los Angeles” in The Day of the Locust, a novel about desperate people making meagre livings on the fringes of the film industry: “[T]he people who come to California to die; the cultists of all sorts, economic as well as religious, the wave, airplane, funeral and preview watchers—all those poor devils who can only be stirred by the promise of miracles and then only to violence.” But those flames, licking the roadsides and the horizon against the stygian darkness of the night, are also the flames of hell, toward which the mentally deteriorating Gladys and her hapless daughter are sucked and allured. It is Dante’s Inferno, with its perpetual darkness, its blazing flames, and its ceaseless torments—but it is also tauntingly glamorous.

All this infernal imagery sits beneath a plangent score of vocals, electronics, and conventional instruments (piano and guitar) composed and performed by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis. The music isn’t just haunting, it is haunted, and it bespeaks primeval terror and heartfelt anguish. I’m a native Southern Californian who has driven up and down the canyon roads of the Santa Monica Mountains more times than I can count, but the vicarious experience of that flame-licked road in Blonde still seemed horrifying, and the Cave-Ellis music made the film coherent to me. I watched Blonde three times as I prepared this essay, and on the first round I was ready after five minutes to dismiss it as a cheap melodrama. Then the music took over, and I began to see what Dominik was after. The cinematography by Chayse Irwin rolls along lyrically under the music, switching from bleached-out, Depression-starved early scenes to noir-esque black-and-white and Technicolor-style brilliance as we are led through Monroe’s film career. Blonde is visually gorgeous.

Gladys’s infatuation with the photo of Norma Jeane’s supposed father and her insatiable craving for the man she cannot have are the driving forces in Dominik’s movie that impel her to try to murder her daughter by drowning her in the bathtub. The explicitly homicidal aspects of this episode are not in Oates’s novel—there is a bathtub episode, but it consists of Gladys filling the tub with scalding water and trying to force the terrified girl into it for punitive cleansing. Norma Jeane wrests herself free and runs naked and screaming to the neighbours for help as her mother shrieks, “You’re the reason he went away. He didn’t want you!”

But in Dominik’s movie, the episode is, pointedly, a kind of belated abortion attempt, a prelude to the daughter’s own abortions later on. The curse is hereditary, passed from mother to daughter. Heredity, generation, and then abortion and miscarriage, which are cessations of generation, are the thematic engines of the film. “Because the very father of the child had wished it not to be born, because he had scattered bills across the bed,” a voice-over intones. It’s bone-chilling. After the bathtub debacle, Gladys is taken away to the funny farm and Norma Jeane is carted off to the orphanage. “I’m not an orphan!” the child screams. But of course she is—the object of both parents’ desire to obliterate her.

Dominik doesn’t simply skip over Norma Jeane’s first marriage, he also excises much of the tedium in Oates’s novel about the fictionalised orphanage and its denizens, who aren’t very interesting (one of them, the butch-ish “Fleece,” Artful Dodger to Norma Jeane’s Oliver Twist, probably had a much larger role in Oates’s first draft). He also removes an invented succession of married droolers and gropers who are unable to keep their minds and hands off the sweater-girl teenager. Instead, he jumps straight from the exterior shots of the orphanage to Hollywood, as Norma Jeane transforms herself into Marilyn Monroe.

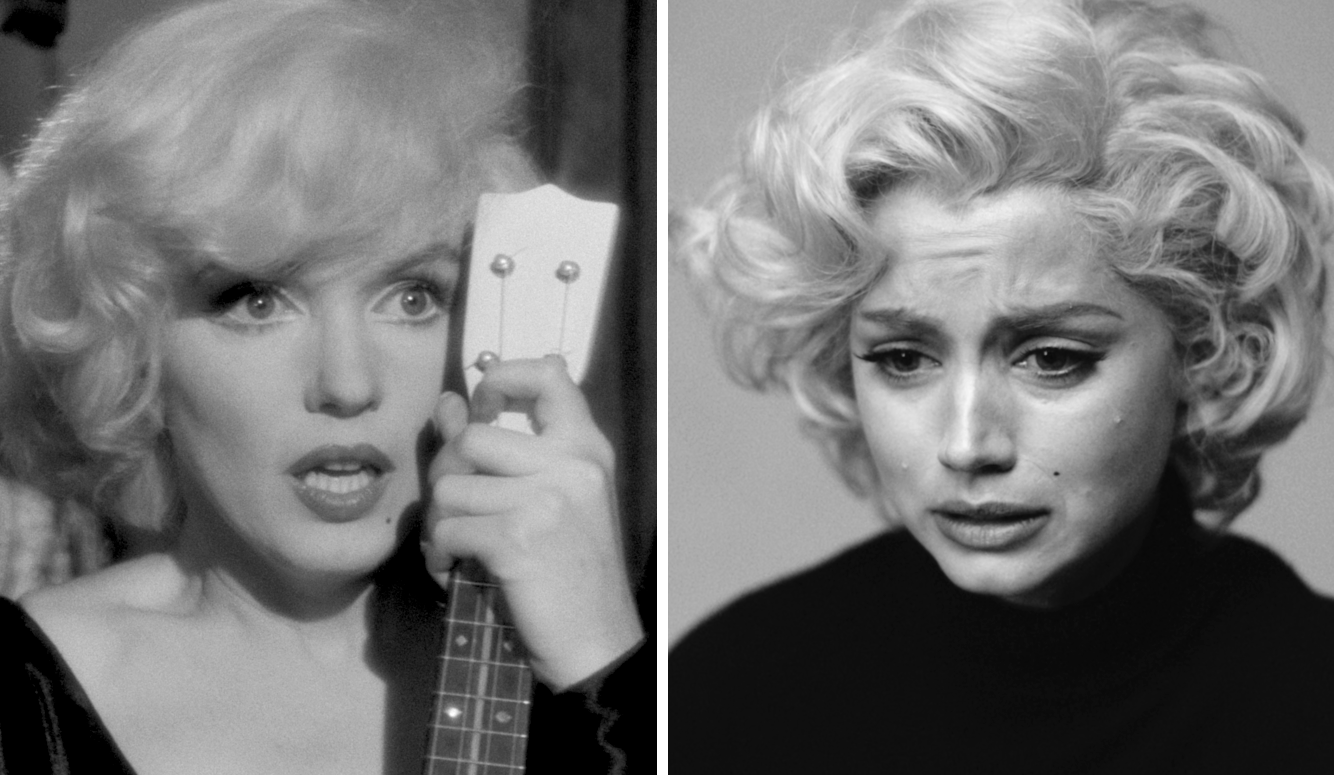

It’s hard to heap enough praise on the performance of Ana de Armas in the title role. She is a natural Latin brunette, with brunette colouring like my own Peruvian mother, and before I saw Blonde, I was dubious that she could pull off the portrayal of a star and icon whose pearly peaches-and-cream skin was essential to her allure. Yet de Armas manages to accomplish exactly that illusion, looking more like Marilyn Monroe than Marilyn Monroe herself. She recreates iconic scenes from Monroe's movies—the rendition of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, for example—with such precise fidelity that it’s hard to believe we’re not viewing actual clips. It’s only when you look at side-by-side photos, such as the movie’s reconstruction of a famous 1957 shoot of Monroe in a blue polka-dot sundress being embraced by Arthur Miller, that we realise the two women don’t really resemble each other physically at all. What de Armas does best is replicate the incandescent, ever-so-slightly fake smile that Monroe could turn on like a lightbulb whenever cameras or fans spotted her, switching out of whatever misery or drug haze she happened to be enveloped in at that moment.

Still, Dominik’s abrupt cut from the shrieking lost child to the performer on the professional make is a glaring narrative weakness. How exactly did this happen in a 1940s Los Angeles overcrowded, as it still is, with young wannabe stars who also had pretty faces and busty figures? He tries to paper over the sudden transition with a a clichéd montage of whirling early-Monroe pinups to the ironically chosen tune of “Every Baby Needs a Da-Da-Daddy” from her awful 1948 film Ladies of the Chorus—a clever play on father-hunger that doesn’t really work. (And why, later on in the movie, do Cass and Eddy G. succeed in blackmailing DiMaggio by threatening to release some of those early nude photos? Hadn’t everyone in America, including DiMaggio, already seen them in Playboy?)

But the abrupt flash-forward does accomplish what Dominik wanted to emphasise: that Norma Jeane has entangled herself in a situation she cannot control. She is lured to the Studio by powerful but unseen forces just as her mother was. And it is a deadly lure. In Dominik’s film, Marilyn Monroe’s career is bookended by two ugly acts of sexual violation: the anal rape by “Mr. Z” at the beginning, and an extended episode of fellatio with “the president” near the end, while he lies on a hotel-room bed sparring on the phone with J. Edgar Hoover and watching a science-fiction flick on television (a rocket lift-off, of course).

That second scene, filmed from JFK’s point of view with graphic frankness, is probably what earned Blonde its NC-17 rating (a first for Netflix). It is so extended, and so deliberately degrading to its drug-dazed subject—delivered to the president’s room nearly unconscious by the Secret Service (“Miss Monroe”) just months before her death—that I have never been able to watch it in full. After that, the president throws her onto the bed and has his way. A Secret Service-monitored abortion follows that is even more nightmarish than her first one.

The two post-stardom marriages are disasters, just as they were in real life. The “ex-athlete” is a half-civilised Italian brute who knocks his wife around when he learns about the nude photos, and again when he sees the image of her with her dress up in The Seven-Year Itch. (He’s probably not unlike the real-life Joe DiMaggio, who was notorious for his primitive manners and general thuggishness.) The “playwright” seems more solicitous and loving, especially when she stumbles and miscarries at their beach retreat, but then she visits his desk and discovers that he is using her neuroses and their conversations as material for his plays. (Miller’s a clèf 1964 play, After the Fall, was widely denounced for exploiting the couple’s marital confidences and portraying Monroe, by now dead and unable to defend herself, as whorish and self-destructive.)

But the really—and surprisingly—satanic figure in the movie is Cass Chaplin, who is the sadistic instrument of her total ruination. He is the one who introduces her to three-way sex—that is, sex for bottomless sensation—and also to the drugs that will ravage her looks, destroy her career, and ultimately kill her. Xavier Samuel gives the film’s sleeper performance as Cass, with exactly the right combination of boyish good looks and winking insinuation, as he and Eddy G use their own melodramas of supposed rejection by their famous fathers to manipulate Norma Jeane’s crippling insecurities about her parentage. It is they who play upon the lure of Hollywood stardom and the adulation of countless fans that will presumably make up for the love that is missing. It is they who drive her to the billboard of her 1953 breakout movie, the noir-in-Technicolor Niagara, where she is sprawled for all the world to see, overcome with passion above the roaring falls. “An actress wants to be seen,” Cass tells her with the suave verve of the Father of Lies as he caresses her in front of a bathroom mirror. “An actress wants to be loved by a multitude of people.”

And so she is in Dominik’s movie, except that the “multitude”—the hordes of men with their reporters’ flashbulbs popping and the chanting of “Mari-lyn!” at her premiers or at the grate scene in The Seven-Year Itch where all eyes are fixed on her underwear—is a sea of male faces and grimacing open mouths distorted by lust, greed, and envy. It is horrible, but it is also irresistible. It is something that Norma Jeane wants. And wants enough to kill the baby that Cass has planted inside her (and to whose fate Cass displays indifference). We can see the payoff, too, while it lasts: the billboard fame, the massive fandom, the beautiful clothes and furs, the top-shelf men with whom to mate.

It is Cass and Eddy G who wreck her marriage to DiMaggio with blackmail. But Cass’s coup de grâce is his final destruction of Norma Jeane’s soul and body after she has already been terminally weakened by drink and drugs (her dealer in Dominik’s movie is another Hollywood creature, her makeup man—the one who creates the persona that will endear her to the camera). In both the book and the movie, the anonymous letters Norma Jeane receives from a man who signs off as “your loving father” or “your tearful father” turn out to have been forged by Cass, something she learns after his death via a package mailed to her by Eddy G.

This is where Dominik makes a significant departure from Oates’s novel, in which the delivery of the package is just one more piece of bad news for Norma Jeane during her final days. Her death, an exceedingly protracted affair that consumes pages, comes not at her own hands, but at those of the Sharpshooter. But in Dominik’s film, the revelation about the letters is pivotal and it is an act of purest malice. Handwritten inside a sappy greeting card featuring a little girl wearing a nursery-rhyme bonnet, it reads, “There was no tearful father. Love, Cass.” The word “Love” is crossed out. Already addled and disoriented from whatever she has been taking from the nest of bottles at her bedside, her screams are the sound of unendurable pain. Then she climbs into the rumpled bed with as many more pills as she can swallow. It is to be hoped that somewhere, in death, she will at last find merciful respite for her ruined soul.

This was not Marilyn Monroe’s real life. But then again, there is a way in which it was. The real-life Marilyn Monroe really was cursed by her heredity, and she really did destroy herself, whether accidentally or intentionally. The curse of heredity and the possibility of self-destruction are realities for everyone. As are the temptations. Everyone has a Hollywood—a Studio—to lure him to ruin as it did Marilyn and her mother, Gladys. The virtue of Andrew Dominik’s Blonde is that it strips away more than a half-century of sentimental folklore and dull-witted feminist ideology surrounding the Marilyn Monroe myth. It presents a myth of its own, but it is one that reveals some terrible truths.