Activism

Mailer and the Second Wavers

“The Prisoner of Sex”—in both magazine and book form—was largely a baroque riposte to Kate Millett’s bestselling feminist polemic Sexual Politics.

The March 1971 issue of Harper’s was one of the most famous—and notorious—that the magazine had published in its then-121-year history. Even now, 50 years later, it is still just as famous and just as notorious. The issue consisted almost entirely of a cover-story essay by Norman Mailer (then aged 48) entitled “The Prisoner of Sex,” that ran into tens of thousands of words and declared war on the movement then known as “women’s liberation.” Within two months, the essay appeared in slightly altered form as a book, also entitled The Prisoner of Sex, and shot to the top of the bestseller lists. Mailer was already infamous in feminist circles for such remarks during media interviews as “All women should be kept in cages” and “[T]he prime responsibility of a woman probably is to be on earth long enough to find the best possible mate for herself, and conceive children who will improve the species.” (He maintained that both statements were testimony to women’s powers.)

At the time “The Prisoner of Sex” appeared, Mailer had already burned through four of the six wives he would marry, and fathered six of his nine children, at least one by each of his spouses. In 1960, he had made headlines for stabbing his second wife, Adele Morales, during a rowdy all-night party in Greenwich Village. Morales fully recovered and declined to press charges (although the marriage stumbled to its end two years later), and Mailer was sent to New York’s Bellevue Hospital for psychiatric observation, then placed on three years’ probation. Over the ensuing months, “The Prisoner of Sex” became the subject of a sustained attack in print and on television by such public-intellectual luminaries as Germaine Greer and Gore Vidal.

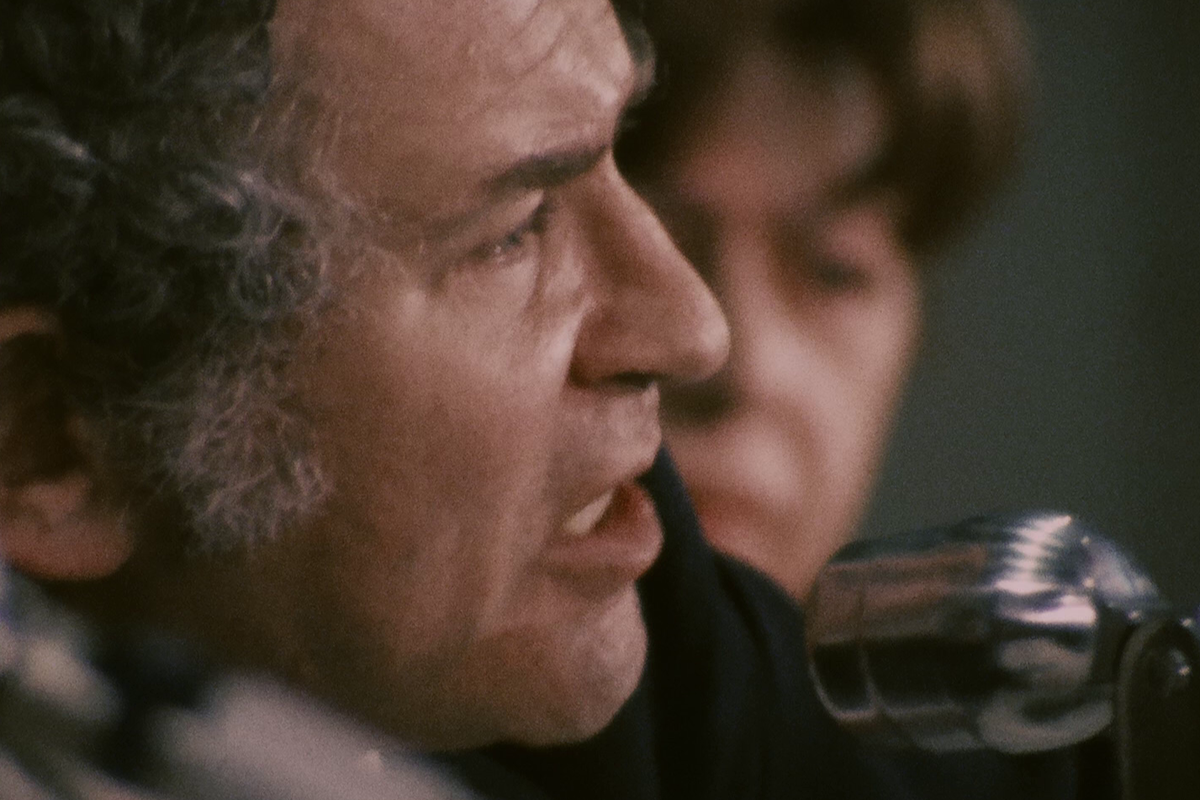

Most notably, the essay was memorialized in a debate entitled “A Dialogue on Women’s Liberation.” The event was held on April 30th, 1971, at the Town Hall, a performance space in midtown Manhattan, and featured Mailer, Greer, the literary critic Diana Trilling, the president of the National Organization for Women (NOW)’s New York chapter Jacqueline Ceballos, and the lesbian polemicist Jill Johnston. The city’s intellectual-elite were all in attendance and the 1960s cinéma verité documentarian D.A. Pennebaker sneaked into the auditorium with two other cameramen to film the debate. It was rumored that Pennebaker’s involvement was at the instigation of the publicity-hungry Mailer, who had previously collaborated with the filmmaker on three avant-garde films. Pennebaker’s footage was eventually edited by Chris Hegedus (who later became his wife) and turned into a 1979 documentary entitled Town Bloody Hall. In 2017, the Wooster Group, an experimental theater company in Manhattan, restaged Town Bloody Hall as a Mailer-bashing play, The Town Hall Affair, that reminded the New Yorker writer Rebecca Mead of Donald Trump’s “arrogant objectification of women.”

“The Prisoner of Sex”—in both magazine and book form—was largely a baroque riposte to Kate Millett’s bestselling feminist polemic Sexual Politics. Published in 1970, Sexual Politics had been the academic salvo (although not the only representative) of a radical wing of second-wave feminism that managed to displace overnight in the public imagination the middle-class, “respectable” wing of the movement represented by Betty Friedan’s 1963 monograph, The Feminine Mystique. Friedan had argued that women’s emancipation should be pursued via legal changes that would help transform women from unpaid housewives into equal participants in economic and political life. Millett—whose unsmiling face was turned into an icon of women’s liberation by its appearance on a 1970 Time magazine cover—went many Marxist steps further, attacking “patriarchy” as a pervasive and brutal system of male domination intended to objectify women economically, politically, and personally.

Sexual Politics was an amplification of Millett’s doctoral dissertation in English literature at Columbia University, so it singled out three male 20th-century novelists for condemnation who had focused on explicitly sexual subjects—Henry Miller, D.H. Lawrence, and Mailer. Blasting past any aesthetic analysis of their works, she castigated all three as primarily “sexual politicians… concerned with a social order in which the female would be perfectly controlled.” Literature, she argued, is essentially an epiphenomenal manifestation of political power structures; in that sense she was among American academia’s first postmodern theorists. She was also perhaps the first cultural Marxist, defining the female sex as an oppressed class. Millett contrasted what she saw as themes of brutish male domination of women via sexual conquest in the work of these three men with the works of the French novelist and playwright Jean Genet, whose fictionalizations of his experiences as a petty criminal, homosexual prostitute, and career prisoner, she admired. Genet’s narratives of pimps, drag queens, and sadistic male-on-male prison sex, Millett argued, were actually instructional parodies of “the power structure of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ as revealed by a homosexual, criminal world that mimics with brutal frankness the bourgeois heterosexual society.”

Millett denounced Miller’s sexually graphic (and long-banned) novels as exercises in “the pleasure of humiliation” of women, typically described in unappetizing detail. She accused Lawrence of indulging in “an increasing fondness of force” in certain of his novels that feature highly educated, artistically sensitive women surrendering to men of primitive masculinity (Lady Chatterley’s Lover was not Lawrence’s only foray into this topos). As for Mailer, Millett targeted his 1965 novel, An American Dream, in which the first-person narrator, Stephen Rojack—a Harvard-educated World War II veteran like Mailer himself—strangles his estranged wife after a quarrel in which she belittles him sexually. The murder is an existential catharsis for Rojack, who is transformed from his hollow previous life as college psychology professor and talk-show host into something more real and authentic, if decidedly violent—immediately after the crime he has rough anal sex with the housemaid in an act close to rape. Millett called Mailer “a prisoner of the virility cult” whose “powerful intellectual comprehension of what is most dangerous in the masculine sensibility is exceeded only by his attachment to the malaise.”

The Harper’s article and its subsequent book version were quintessential Mailer, with all the faults and virtues of that unique genre. During his early career, Mailer’s reputation had been mostly as a novelist of varying critical success. His widely acclaimed first novel, The Naked and the Dead, based on his World War II experiences in the Philippines, had made him a celebrity at the age of 25, but he followed it with several others that critics largely panned, including An American Dream. Between works of fiction, he led a boisterous and well-publicized personal life, helped found the Village Voice, dabbled in money-sucking avant-garde filmmaking, and in 1969 ran unsuccessfully for mayor of New York City.

But almost inadvertently—in magazine articles for Esquire and other periodicals that paid more reliably than trying to write the Great American Novel—he became a pioneer of 1960s New Journalism, which used the techniques of fiction in nonfiction reporting. (He had dress-rehearsed this change of genre in a 1959 collection of essays as well as fiction, Advertisements for Myself.) A 90,000-word cover story for Harper’s about his participation in an anti-Vietnam War protest at the Pentagon in 1967 became a 1968 book entitled The Armies of the Night that won him the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction. The Prisoner of Sex employed literary approaches that Mailer had perfected in The Armies of the Night. Like other New Journalists, Mailer made himself a third-person participant—indeed the protagonist—in the action he narrated. This strategy enabled him to portray himself, with large doses of self-mockery, as the much put-upon victim of whatever malign forces he deemed were arrayed against him.

In The Armies of the Night, he had been “the Novelist,” contriving to get arrested and then complaining about the breakfast menu in jail and wondering whether he should give away the bail money he had brought with him or use it to get himself out. In The Prisoner of Sex, he was “the Prisoner”—of “the legions of Women’s Liberation”:

…a vision of thin college ladies with eyeglasses, no-nonsense features, lips as thin as bologna slicers, a babe in one arm, a hatchet in the other, gray eyes bright with balefire. Four times beaten at wedlock, his respect for the power of women was so large that the way they would tear through him (in his mind’s eye) would be reminiscent of old newsreels of German tanks crunching through straw huts on their way across a border.

In a lengthy prelude, he either amused or exasperated his readers by recounting his dashed expectations of receiving the Nobel Prize for literature, a lunch he had eaten with a hostile but “never unattractive” Gloria Steinem, and a deadpan narrative of the six weeks he had spent during the summer of 1970, after his estrangement from his fourth wife, the actress Beverly Bentley, playing stay-at-home parent to five of his children in a Maine cottage. He wrote that “he could be a housewife for six weeks, even six years, if it came to that”—although in fact, as he admitted, he’d had to recruit his sister, his mistress, the two older of his daughters there, and a full-time cleaning lady to bring order to the ensuing chaos.

Mailer’s writing style, honed (if that’s the word) by his facility at turning out massive amounts of copy in short order (he wrote all 90,000 words of The Armies of the Night in two months), was in the classic American tradition of verbose rhetorical extravagance exemplified by Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, and Allen Ginsburg: often brilliant, often merely wordy and overblown. It is hard to know what to make of this nearly interminable sentence in which Mailer avers that the “male contempt of the pussy” hammered by Millet can be evenly matched by what he calls female “penis contempt”:

Now penis contempt may well accompany the others, for the look in the woman’s eye bemoans the fact that she is not a man, since if she were a man, or better still, a woman with command of a phallus entrusted to her, she would know how to use it, God she would know how to use it better than a man, which may not be an unfair portrait of a woman thinking across the gulf of sex: whereas a man is not often ready to explain that a phallus is not a simple instrument but a contradictory, treacherous, all-too-spontaneous sport who is sometimes the expression of a part of oneself not quite under Central Control, indeed often at odds with the will.

Is this bombast, misogyny, or a profound recognition of the terrifying vulnerability that men as well as women bring to the sexual act? Mailer’s preternaturally vivid prose, dumped onto the page in mounds like scoops of ice cream with nuggets of humor folded into the boozy apocalyptics, has a hypnotic quality that makes The Prisoner of Sex, for all its shortcomings, impossible to put down.

For some reason, Mailer never got around to responding specifically to Millett’s critique of An American Dream, except to say she had misread his work of fiction as an instruction manual on “how to kill your wife and be happy ever after.” (During the Town Hall event he railed repeatedly at the feminists present for not being able to distinguish between the words uttered by fictional characters and their creators.) Instead, he tore into Millett’s habit of quoting Miller and Lawrence selectively and out of context in order to make polemical points. Mailer had majored in aeronautical engineering at Harvard, and he used his acumen to drill down with mathematical precision into Millet’s textual distortions, citing passage after passage comparing Millett’s truncated quotations to their less malign authorial originals.

But his real quarrel was with Millett’s assertion that the sexes were exactly alike except for accidents of genitalia, and that men had contrived over the centuries—by imprisoning women in cycles of enforced monogamy, childbirth, and economic dependency—to bend them to their wills, sexual and otherwise. Millett argued for an end to all societal taboos against homosexuality, non-marital sex in general, out-of-wedlock childbearing, prostitution, and the double-standard, with the goal of creating a “permissive single standard of sexual freedom” that would make women the equals of men. Mailer derided this proposal as creating a “free market for sex, a species of primitive capitalism where the entrepreneur with the most skill and enterprise and sexual funds could reap the highest profit—the adoration of countless mates and mistresses in that ubiquitous world where men and women were as interchangeable as coin and cash.”

Besides Millett, Mailer attacked other second-wave feminists who had made headlines by demanding release from perceived male domination. Among them: Anne Koedt, whose 1970 essay “The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm” argued that the clitoris was the primary source of women’s sexual pleasure, so that conventional male-female sex was neither necessary nor necessarily normal; and Ti-Grace Atkinson, whose 1969 pamphlet “Radical Feminism” advocated the development of “extra-uterine conception and incubation” that would disconnect sexual intercourse from “[s]ociety’s means to population renewal” so that women would no longer have to “bear the burden of the reproductive process.” “[I]n order to improve their condition… [w]omen must, in a sense, commit suicide, and the journey from womanhood to a society of individuals is hazardous,” Atkinson declared. Koedt and Atkinson were probably among the most radical of the second-wavers, but there were others. Alix Kates Shulman wrote “A Marriage Agreement” in 1969, which proposed to turn wedlock into a tit-for-tat business partnership (“Husband does all the house-cleaning in return for wife’s extra child care”). Contributors to Robin Morgan’s 1970 anthology Sisterhood is Powerful lauded two medical inventions of the 1960s and early 1970s—the birth-control pill and the suction-abortion machine (“The entire process takes about two minutes,” Lucinda Cisler enthused)—that promised to level the sexual and career playing-field for women at last.

Mailer decried all of this as the “technologizing of sex.” He was already notorious for his opposition to contraception and masturbation as sterile dead ends of sexuality, and in The Prisoner of Sex he doubled down. He described the second-wavers’ call for a single standard of sexual freedom as “all part of the huge revolutionary statement that all fucking high and low, by any hole or any pit, was pleasure, and pleasure was the first sweetmeat of reason… Well, conception stood in the way of reason, for conception was embarkation on a train whose stations were obligation and guilt.” The prospect of conceiving a child, relished or dreaded, rendered sex serious. And the fact that conception took place inside the body of a woman rendered the difference between the sexes the most important of all human differences:

Men were by comparison to women a simple meat; men were merely human beings equipped to travel through space at a variety of speeds, but women were human beings traveling through the same variety of space in full possession of a mysterious space within… Women, like men, were human beings, but they were a step, or a stage, or a move or a leap nearer to the creation of existence, they were—given man’s powerful sense of the present—his indispensable and only connection to the future…

Mailer asserted, contra Millett, that Genet’s literature of prison homosexuality, far from parodying heterosexual males’ subordination of females, realistically portrayed a “world where everything is homosexual and nowhere in the world is the condition of being a feminine male more despised… For whatever else is in the act, lust, cruelty, the desire to dominate, or whole delights of desire, the result can be no more than a transaction—pleasurable, even all-encompassing, but a transaction—when no hint remains of the awe that a life in these circumstances can be conceived.” By this measure, heterosexual coupling with contraception was little different from homosexual encounters, Mailer averred. But this, he wrote, was exactly the aim of the feminist movement—to “technologize” women, turning them, unencumbered by the naggings of their reproductive systems and living atomized without the freight of either babies or prudish inhibitions, into efficient, career-oriented “units” of production in a brave new world—mechanized, contractual, and run for the benefit of the corporate state, but where they could count on their sexual desires being satisfied by someone or something. He called this phenomenon “Left totalitarianism,” marked by its mix of sexual radicalism, bureaucracy, and faith in science. He called himself a “Left conservative.” That was a fair summary.

Released exactly at the time when nearly every college-educated woman in America, schooled in Friedan and then electrified by Sexual Politics and its counterparts, was starting to call herself a feminist and resonating vicariously to second-wave radicalism, The Prisoner of Sex garnered enormous attention, most of it negative. On March 4th, 1971, within days of the publication of the magazine version, Willie Morris, the 36-year-old editor-in-chief of Harper’s who had commissioned the piece, resigned under fire. Morris, regarded as a 1960s wunderkind, had also commissioned the magazine version of The Armies of the Night, and his penchant for edgy, if critically acclaimed New Journalism narratives had cost the magazine advertising. This time the owners of Harper’s were said to be disturbed by the number and frequency of four-letter words in Mailer’s article, some in quotations from Miller and Lawrence, some in the writings of the feminists Mailer scrutinized, and some in Mailer’s own vocabulary choices. Then came the book reviews. Some were flattering. The critic Anatole Broyard, writing in the New York Times, called The Prisoner of Sex “a love poem” to women and Mailer’s “best book.” Most women seemed to think otherwise. Novelist Brigid Brophy’s review, also in the New York Times, was scathing. She called the book “an appreciative meditation by Norman Mailer on Norman Mailer. It establishes merely that if Kate Millett could put him down with bad logic and bad prose, he can puff himself up with more and worse of both.”

But it was Mailer’s appearance at the Town Hall event on April 30th that firmly, perhaps finally, placed him and his views on women beyond the ideological pale. His double role—he was both panelist and moderator—had been the idea of the dancer and choreographer Shirley Broughton, who liked to bring artists and celebrities together in symposia that she called the Theater of Ideas. She had hoped to induce Millett to join the panel, but Millett refused to debate Mailer. Other leading second-wave feminists also declined, including Friedan, Steinem, Ti-Grace Atkinson, and Susan Brownmiller, author of Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. They were apparently offended by the notion of a male moderating a panel on feminism, and they also might have wondered whether they would be participating in a publicity stunt orchestrated by Mailer himself. Broughton did manage to recruit Jill Johnston and the literary critic Diana Trilling. Johnston was something of a cult figure. Technically she was the dance critic for the Village Voice, but her column had long since evolved into a rambling, free-association exploration of her sexual orientation. (Her book Lesbian Nation, a compilation of those columns, would follow in 1973.) Friedan headed NOW at the time, and she sent Jacqueline Ceballos to represent the organization in her stead.

Finally, there was the Australian-born Greer, in New York promoting her internationally bestselling first book, The Female Eunuch. The Female Eunuch was even more popular with women readers than Sexual Politics; an excerpt appeared in the March 1971 issue of McCall’s, a leading middlebrow women’s magazine. Greer, although academically trained (she had a PhD in English literature from Cambridge and a teaching post at the University of Warwick), knew how to write in a zesty, racy style that never shied away from the outrageous, as, for example, when she famously advised women: “[Y]ou might consider the idea of tasting your own menstrual blood—if it makes you sick, you’ve a long way to go, baby.” Mailer had quoted this passage with a degree of awe in The Prisoner of Sex: “[N]ow women were writing about men and themselves as Henry Miller had once written about women.”

The thesis of Greer’s book was that women had internalized this male revulsion—exacerbated by consumerist, cleanliness-obsessed suburban culture and the stifling nuclear family—at the grosser aspects of their reproductive functions. They had weakened and desexed themselves—taken on “impotent femininity”—in order to make themselves acceptable, and then, as wives and mothers, became resentful, nagging shrews who damaged their children irrevocably. Greer urged women to flaunt their sexuality and leave their husbands or, preferably, not marry at all, and bring up their children in free-form communal arrangements in which the youngsters would essentially “raise themselves,” liberated from the stifling “Oedipal” dynamics of the middle-class Western household.

Greer was already a celebrity in Britain, annoying other feminists by flaunting her own sexuality and announcing that just as men hated women, women also hated women—a claim which undercut the idea that sisterhood was powerful. In The Female Eunuch, she had mocked NOW and its push for legal tinkering with the system instead of outright rebellion. The prospect of her confrontation with Mailer was irresistible. The Town Hall sold out all 1,500 of its seats and went to standing room only, even though the tickets cost $25, about $161 in today’s dollars. The attendees, zoomed into close-ups by Pennebaker’s telephoto lenses, included such notables of second-wave feminism as Friedan, Steinem, Robin Morgan, Susan Sontag, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Cynthia Ozick, as well as Broyard and the poets Gregory Corso and John Hollander. What followed was a raucous piece of performance art that gave the audience its money’s worth. According to Greer, in an essay for the September 1971 issue of Esquire entitled “My Norman Mailer Problem,” the Town Bloody Hall rushes became the subject of a legal dispute between Mailer and Greer over whether Pennebaker had the right to use them. In any event, the reels languished on Pennebaker’s shelves for several years until Hegedus, newly hired by Pennebaker, viewed them, decided to edit them, and proved that a panel of five talking heads sitting at a table on a stage can make for rip-roaring entertainment. (The title of the documentary came from Greer’s exasperated cry that she was being “heckled” by Mailer at the “Town bloody Hall.”)

From the beginning, it was a contest between the outsize personalities of Greer and Mailer over who was to own the evening. Greer, six feet tall, with a mane of brunette hair and inch-long eyelashes, had attired herself in a fur stole and a long black sleeveless dress that showed off her arms and shoulders. Around her neck she wore an enormous silver pendant: a Venus’s mirror with a raised fist inside. At 32, she was at the peak of her good looks, which coincided with the peak of her readerly popularity (none of the 16 books she published after The Female Eunuch sold so well). It wasn’t hard for her to upstage Ceballos and Trilling in their ladylike suits and Johnston in her blue jeans and denim jacket. She sat herself down next to Mailer, the latter looking natty in a pinstripe suit and a frizz of graying corkscrew curls. Pennebaker’s hand-held cameras feasted on the electricity generated by the physical proximity of the two. “There was just so much sexual tension between Norman and Germaine, and I knew I wanted to keep that element in the film,” Hegedus recalled in a 2004 video interview accompanying the release of the film on Blu-ray. “But also I wanted to keep the humor, because it was very funny,” Hegedus said. “Norman was witty and funny, and Germaine was. And Jill was hysterical.”

Still, except for a list of NOW demands (wages for housework, pensions for retired housewives) read by Ceballos that received only polite applause, the evening was essentially a spectacle of Mailer as Prometheus chained to the rock, with the eagle, or in this case, a convocation of feminist eagles, pecking at his liver. Only occasionally was there applause for him, or for his half-hearted defender on the panel, Diana Trilling. Greer, for example, who was next up after Ceballos, used her time at the microphone to blowpipe lethal darts at Mailer and his turbulent marital life: the “masculine artist, the pinnacle of the masculine elite… more killer than creator.” “The masculine artist’s path,” she said, was “strewn with the husks of people worn out and dried out by his ego,” Greer continued. To masculine artists, “we were either low, sloppy creatures or menials, or we were goddesses. Or worst of all we were meant to be both, which meant that we broke our hearts trying to keep our aprons clean.” There was the obligatory reference to Sylvia Plath. She got a sustained ovation. Come the feminist “revolution,” Greer declared, art “will be the prerogative of all of us and we will do it as those artists did… who made the cathedral of Chartres or the mosaics of Byzantium, the artists who had no ego and no name.” Another sustained ovation. Mailer shot back that this flight of romantic historicism, from women’s liberation to utopian collectivism, was “a species of social instrumentality that I call diaper Marxism.” Boos for Mailer.

Next on was Johnston, who (she later revealed) had spent the afternoon drinking at the Algonquin Hotel. She was indeed, as Hegedus recalled, hysterical. “All women are lesbians,” she began. Then, in a slurry monotone, she read a rhythmic monologue that was essentially an early version of slam poetry: “He said, ‘I want your body,’ and she said, ‘You can have it when I’m through with it.’” The audience laughed and cheered. After she had gone on for a while, Mailer informed her that she had exceeded the assigned 10-minute limit for speeches and ought to wrap it up. Boos. Mailer took an audience vote on how many wanted to hear more from Johnston. She lost by a hair—so she left the podium to roll on the floor in a dry-humping session with two female admirers. “Either play with the team,” Mailer suggested, “or pick up your marbles and get lost.” She appealed for additional time. “Come on, Jill, act like a lady,” he said. An attendee called out, “What’s the matter Mailer? You feel threatened because you found a woman you can’t fuck?” “Hey cunty,” Mailer replied. “I’ve been threatened all my life, so take it easy.” Johnston stomped off-stage. The audience loved it.

Trilling, an old-school liberal, tried to split the difference. She said that while she found Mailer’s insistence on the primacy of biology in relations between the sexes, especially his rejection of birth control, prone to go to “dangerous poetic excesses,” she “would take Mailer’s poeticized biology in preference to the no biology at all of my spirited sisters.” She could not resist criticizing “Miss Greer,” declaring that she was not impressed by her theory of the “Oedipal” nuclear family that “rejects children.” “One of the characteristics of oppressed people is that they always fight among themselves,” Greer retorted during a subsequent disagreement. “I don’t feel as oppressed as you do, and I’m not fighting with you,” said Trilling. “I have a great deal of loyalty to my sex and I’ve had it for a very long time. But that doesn’t mean I can be indiscriminate about the positions that I subscribe to just because they’re put forward by other women.”

Mailer began his own contribution to the discussion by telling his “dear old friend” Diana Trilling that she had, as usual, misread him. “What I was trying to say in my usual incoherent fashion in The Prisoner of Sex,” he went on, “was that biology—or physiology, if you will—is not destiny, but it is half of it. And if you try to ignore that fact, you then get into the most awful totalitarianism of them all—because it’s a Left totalitarianism… If we get a left-wing totalitarianism, that will mean the end of all of us, because we will have nothing but scrambled minds trying to overcome the incredible shock that the destruction of human liberty came from the Left and not the Right. And there is an element of women’s liberation that terrifies me. It terrifies me because it is humorless, because, with the exception of Germaine Greer’s book on The Female Eunuch, there’s been almost no recognition that the life of a man is also difficult, and that of all the horrors that women go through, some of them absolutely determined by men, even more of them, I suspect, determined by themselves.”

After that, it was question time and a rout. The heavyweights in the audience had been seated ringside in order to prime them, and the taunts poured in. Betty Friedan accused Mailer of defining women in essentialist fashion as “the eternal face of Eve.” “Women have the right to define our agency,” Friedan said. With a wave of his hand, Mailer responded: “I simply don’t know what you’re talking about.” Boos. “Betty, you’re just making speeches.” More boos. Susan Sontag called Mailer “patronizing” for introducing Trilling as a “foremost lady literary critic.” “I will never use the word ‘lady’ again in public,” Mailer promised sardonically. (His half-hearted attempt to provide a serious answer didn’t go down any better.) Feminist writer Lucy Komisar accused Mailer of writing novels that promoted male sexual violence, to which Mailer replied, “I look forward very much to the advance of women’s liberation because women are finally going to have to come into contact with the best aspect of the male brain which is its modest accuracy.” His explanation of the difference between a character’s viewpoint and that of the author segued into a discussion about the militaristic nicknames Mailer may or may not have given to his own penis. Some additional levity was provided by the following exchange with Cynthia Ozick, who had just described Mailer (with apparent sincerity) as “a sacerdotal, sexual transcendentalist priest”:

OZICK: Mr. Mailer, in Advertisements for Myself, you said—quote—”a good novelist can do without everything except the remnant of his balls.” For years and years I’ve been wondering, Mr Mailer, when you dip your balls in ink, what color ink is it? [laughter]

MAILER: Miss Ozick, if I don’t find an answer quickly, we’re gonna have to agree that the answer is yellow. [more laughter] I will cede the round to you. I don’t pretend that I’ve never written an idiotic or stupid sentence in my life, and that’s one of ’em. [laugher and applause]

But the Q&A was a mostly fraught and bad-tempered affair. Anatole Broyard asked Greer what women were asking for. “You may as well relax,” she snapped, “because whatever it is they’re asking for, honey, it’s not for you.” She scoffed that Mailer’s domestic arrangement in Maine had been “four nurturing women and three boys: Norman and his two sons.” Mailer’s response: “Did you come all the way from Australia to land a cheap shot like that?” He said that women’s liberation had “lesbian overtones… a detestation of men.” Then a member of the audience named Ruth Mandel rose to announce that she had no need for children. “Biologically,” she explained, “I don’t find myself tied down to my body so that it limits the definitions of me… Is [Mr. Mailer] tied down so much to his body that he can’t define himself outside of it?” Here Mailer tried to put a fine point on what was bothering him:

MAILER: What I was trying to say in The Prisoner of Sex over and over again is that there’s nothing in Women’s Liberation… that deals with what I think is the heart of the problem… [which] is that human nature strives in the way it works against painful, torturing paradoxes. And I’m quite aware that many women—perhaps most of the women on Earth by now—don’t want to have children; don’t want to be in that sexual organic biological game. And maybe they’re right! I don’t know. And I’m not saying “stop them!”; I’m not saying they’re evil; I’m not saying they’re wrong; I’m saying we’re gonna have to find out. Human history has got to the point where the majority of women are essentially rebelling. But we could save a lot of time if we cut out the crap and the name-calling. Because the one thing that is really gonna close off the ranks of men against the power of this movement is precisely the fact that men have had to deal with the abysmal lack of a sense of justice that women have for their point of view. Now you may counter by saying, “Yes, but that’s just a male sense of justice.” Alright and maybe it is. But in the dialogue, you’ve got to allow us our terms as well… Let me point out to you where the paradox of male and female violence takes place.

The mention of male violence seemed to inflame the audience (there was already nearly inaudible heckling), but Mailer plunged ahead:

MAILER: You’re asking for a dialogue, well, here it is! This is my half of the dialogue and you can counter it—

HECKLER: We want to teach you!

MAILER: I’ll teach you and you teach me! Fuck you! I wanna teach you too! I mean, fuck you, y’know? I’m not gonna sit here and listen to you harridans harangue me and say “Yes’m! Yes’m!” [smattered applause] Let me aim the point. If a man has sworn that he will not strike a woman and the woman knows that uses that and uses it and uses it, then she comes to a point where she is literally killing that man because the amount of violence being aroused in him is flooding his system and slowly killing him. So she’s engaged at that point in an act of violence and murder even though no blows are exchanged. Now all I’m getting at is that this is the simple existential difficulty of the moment. The argument about the justice in this human relation is where is that point? Because that is where there is absolutely never any agreement—whether it is the man or the woman who is playing with that point. If you women are not willing to recognize that life is profoundly complex, and that women as well as men bugger the living juices out of it, then we have nothing to talk about. Again.

Mailer might have been summarizing his own wedded life. With Beverly Bentley, especially, as she recounted in Joseph Mantegna’s 2010 documentary, Norman Mailer: American, it had been a roller-coaster lurch between tenderness and screaming matches that at least on one occasion ended with his beating her. (Paradoxically, perhaps, he remained on affectionate terms with some of his ex-wives; his third, Jeanne Campbell, starred in his tumultuous 1971 movie Maidstone along with Bentley, and Adele Morales hovered on the set.) But the point that he was trying to make—about the different ways in which men and women express aggression—was lost on the Town Hall audience.

The months that followed produced further controversy. Greer’s Esquire article appeared, and there she averred that her “masculine artist” jabs had been aimed specifically at Mailer’s stabbing of Morales and his inability to live with Bentley. She implied that the Town Hall event had been a façade for Mailer’s efforts to pre-empt her book tour in order to promote his own career, and that he had hired Pennebaker to do the filming, which was supposed to be the exclusive province of the BBC, trailing her on the tour. The legal conflicts to which she alluded apparently petered out, and indeed, Trilling, in her own memoir of the event, said she had seen Greer and Mailer posing together with a copy of The Female Eunuch just before the panel began. Rumors persisted that either the two had slept together or that Greer had hoped they would. Greer denied both rumors, although she told Hegedus in 2004 that she had wanted Mailer’s “approval. I wanted him to find me interesting, intelligent, and attractive.” (One of the paradoxes of the Mailer-Greer fallout is that the two actually had much in common in their anti-modern stances—but it was a commonality that neither ever explored. Their writing styles—hyperbole, self-dramatization, and a tendency to dump every thought that crossed their minds into their prose—were also surprisingly similar.)

Gore Vidal entered the fray in July 1971, writing a 4,900-word article for the New York Review of Books that was ostensibly a review of Patriarchal Attitudes: Women and Society, by the novelist Eva Figes. Vidal paid only perfunctory attention, however, to Figes’s complaints about capitalism and sexual taboos and devoted most of the article to an attack on The Prisoner of Sex. “There has been,” he wrote, “from Henry Miller to Norman Mailer to Charles Manson a logical progression. The Miller-Mailer-Manson man (or M3 for short) has been conditioned to think of women as at best, breeders of sons; at worst, objects to be poked, humiliated, killed.” Five months later, Vidal and Mailer were guests on the Dick Cavett show, along with Janet Flanner, the Paris correspondent for the New Yorker; her prim suit, pumps, and white gloves looked oddly discordant with her enormous physical frame. It was another audience debacle for Mailer.

Waving a copy of Vidal’s article, Mailer proclaimed that Vidal’s writing was “no more interesting than the contents of the stomach of an intellectual cow.” The audience booed. “Gore Vidal,” remarked Flanner, “is the cow on the program.” To which Vidal added: “And Norman Mailer is the veal.” Mailer had good reason to be outraged at Vidal’s insinuation that “the next reincarnation for me is going to be Charles Manson,” as he put it, but he could not get his point across. (The fact that he seemed to be sloshed, lurching across the vast brown 1970s shag rug on the television stage to take his seat, didn’t help.) Neither Flanner nor Cavett (who later said he felt “twinges of guilt about not having treated [Mailer] nicer”) showed much sympathy for his agoniste’s performance. Flanner said she was “bored” by the display, and Cavett told Mailer he could “fold it five ways and put it where the moon don’t shine.” Mailer looked out at his hostile audience: “This joint is loaded with libbers.” And yet, as at the Town Hall, he had a way of sucking the air off the stage. It was impossible for the viewer not to be riveted by his performance.

Mailer was never to return to the subject of The Prisoner of Sex, at least in print. He went on to win a second Pulitzer Prize in 1979, for fiction, for The Executioner’s Song, a novelized but extensively reported account of the Utah murderer Gary Gilmore’s violent life and death by firing squad in 1977. He wrote several more novels and works of nonfiction that received the usual mixed reviews. He had not only lost his battle against the “libbers”; he had lost the war of feminist opinion. When Mailer died in 2007, the novelist Joan Smith, writing in the Guardian, called him “an arch-conservative who pulled off a stunning confidence trick” and a “faux-radical who used the taboo-breaking atmosphere of the ’60s as cover for a career of lifelong self-promotion.” In the Nation, Katha Pollitt wrote: “What a failure of imagination and humanity there is in his ravings about the evils of birth control and women’s liberation, his cult of hatred and domination and violence, his fatuous pronouncements about what women should be (goddesses, whores, mothers of as many children as a man could stuff into them), his pronouncements of doom on a culture that let them get out of their cage.” Rebecca Mead wrote in her 2017 New Yorker article: “What is most shocking about revisiting Town Bloody Hall today—either in the form the Wooster Group presents it, or without their commentary—is the raw misogyny of the language Mailer feels comfortable in using in the public forum that has been provided to him.” It seems that all that can be remembered today about Mailer and women is that he said they belong in cages.

Mailer certainly had his faults, personal and writerly. His marital life invariably included strings of infidelities, even during his last and happiest marriage to the former model Norris Church. His stabbing of Morales might have been mostly owing to drink and the excesses of Greenwich Village bohemian culture, but he did have a genuinely alarming tendency to romanticize lethal violence as a rite of male passage into masculinity. It was a rite that he himself seemed compelled to perform, although non-lethally, in any number of brawls and fistfights with other men, including Vidal, whom he punched with a liquor glass at a 1977 party in another spat over The Prisoner of Sex. In what was surely the most embarrassing episode of his life he used his reputation to help parole the convicted killer Jack Henry Abbott out of a federal prison in 1981. Mailer gave him a job as his assistant and landed him two articles about his prison experiences in the New York Review of Books. Six weeks after his release, Abbott stabbed to death a young waiter in a restaurant who had denied him the use of an employees-only restroom.

The Prisoner of Sex suffers from hasty writing and Mailer’s penchant for indulging in verbal gymnastics at the expense of clarity and argument-construction. Mailer managed to misspell the surname of Valerie Solanas, Andy Warhol’s would-be assassin, whose 1967 SCUM Manifesto (“destroy the male sex”) was one of the books he covered. He overrated as literary figures both Henry Miller and D.H. Lawrence. Miller, at least in the excerpts Mailer provided from Tropic of Cancer, Tropic of Capricorn, and Sexus, basically wrote pornography. His authorial style consisted of jackhammer prose lacking even rudimentary efforts at either characterization or color; it’s all Miller’s first-person narrator shoving various things into the private parts of women who love it. And it is hard not to laugh out loud at the overripe Chatterley sex scenes, with gamekeeper Mellors painstakingly teaching Her Ladyship how to say four-letter words in Nottinghamshire dialect. Mailer’s extended quasi-mystical romanticization of women and their wombs, aligning them with the forces of the universe just because they bear babies, seems over the top even if one agrees with Mailer about the profound biological differences between the sexes.

Nonetheless, it is a brave and important book. Mailer understood that sex isn’t merely about pleasure: obtaining an orgasm from some frictional source or other. Human beings endow sex with meaning. A man wants to know that the woman he is with experiences pleasure from him, and a woman that she is particularly desired. (The absence of these elements is at the root of the sourness and disappointment accompanying today’s hookup culture: the abrupt and crude coitus, the unwanted moves, the nagging suspicion that your partner might have found you revolting—or worse, nondescript—instead of lovely.) The fact that meaning is integral to the human sexual act derives from the fact that the act itself is full of meaning; it is the act that makes life. Mailer had a point in decrying its technological manipulation and the relentless effort to sever the connection between sex and reproduction.

One of the astonishing things about reading The Prisoner of Sex a half-century after its publication is the realization that many of the radical-sounding future phenomena that Kate Millett and Ti-Grace Atkinson demanded and Mailer denounced as dystopian have not only come to pass but are an integral, even humdrum part of everyday life. Even when Mailer was writing in 1971, his distaste for birth control seemed laughably retrograde to everyone but fringe religious traditionalists. Now, of course, we have government-mandated, government-subsidized free contraception, and we seem to be on our way to government-subsidized free abortion as well. We have fairly succeeded in obliterating those supposedly non-essential differences between the sexes; the very word “sex” to denote biological self-identification has been replaced by “gender identity,” a fluid and entirely subjective concept that includes picking one’s own personal pronouns. Indeed, so thorough has been the revolution in this department that Germaine Greer has met the fate of Danton; in 2015, transgender activists tried to push her off the university lecture circuit for refusing to go along with the now-de rigueur proposition that transwomen are really women. There is something ironic about the fact that a long-term consequence of women’s liberation has been the erasure of “woman” as a definable category.

And if we don’t have artificial wombs quite yet, we do have the “surrogate” wombs of Second- and Third-World women hired to gestate fertilized eggs that may or may not have been produced by the people whom the law deems their parents. We do not have children who “raise themselves,” as Greer had hoped, but we have millions of children who might as well be doing so, with fathers and sometimes mothers who have long since disposed of their parenting responsibilities, and millions of other children parked in day care or with nannies. Far from burdening women with housewifery and babies at the expense of career advancement, we have a record low marriage rate and a birthrate that has collapsed to the point of alarm among demographers. We also have a record number of single people—15 percent, double that of 50 years ago—living alone, especially in cities, isolated in rabbit-warren, “high-density” apartment buildings where, during this time of coronavirus, they can neither meet nor mate. All this to the tune of survey after survey indicating that women are actually less happy than they were during the early 1970s.

Mailer was remarkably prescient. In The Prisoner of Sex he wrote about the liberated woman of the future: “She was a way of life for young singles, a species of city-technique. She gave intimation by her presence that the final form of the city was nearer to the dormitory cube with ten million units and the perfect absence of children or dogs.” He was wrong about the dogs. At the Town Hall panel Diana Trilling said “in 50 years we’ll find out” what radical feminism might do to those it would affect. Those 50 years are now up.