Russia

How Russia Evades Western Sanctions

Shady trade routes and oil tankers keep the Russian economy ticking over.

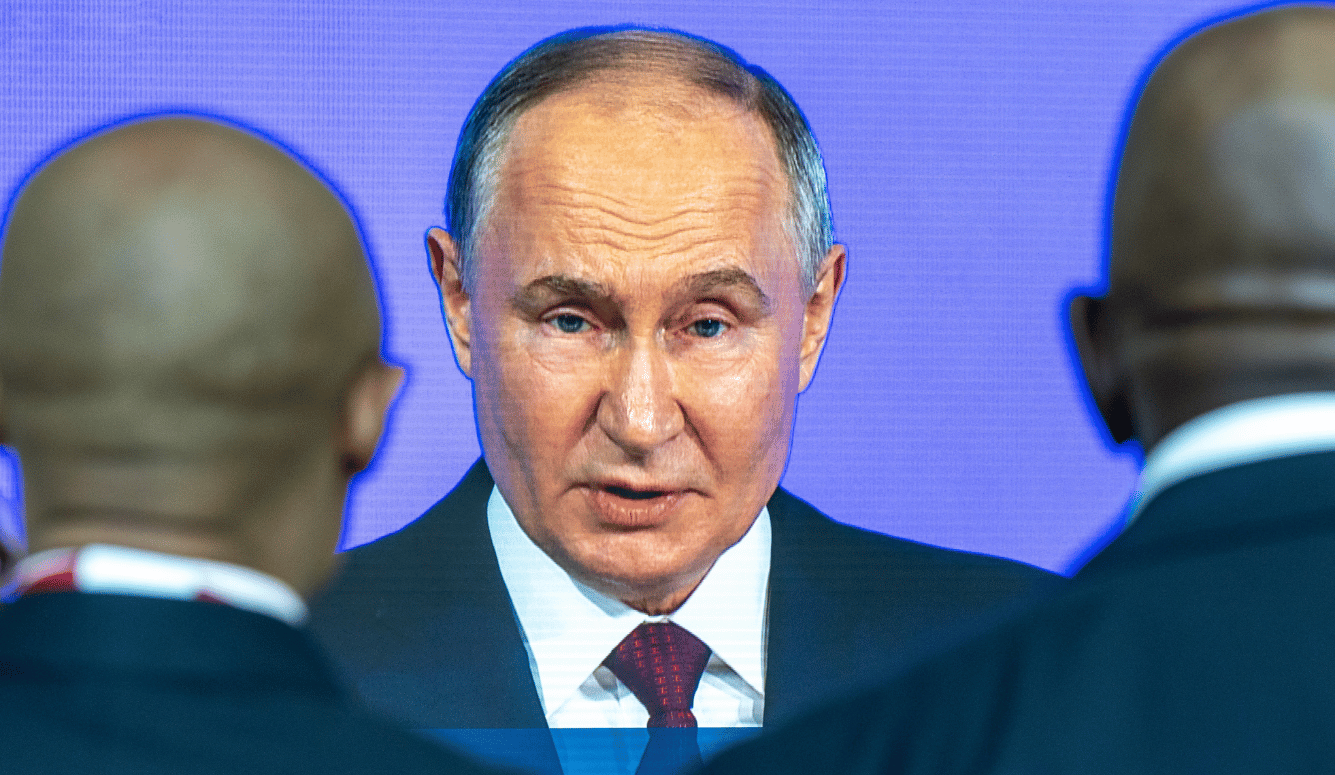

Russia currently exists in a state of economic purgatory. Since Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Western powers seeking to limit his nation’s warmaking capacity have instituted one of the harshest sanction regimes the world has ever seen. Imports of Russian oil, above a certain price, have been outlawed, as have exports of sensitive materials, such as semiconductors, engine parts, and communications equipment,that might find their way into Russian weaponry. The country’s banks have been cut off from SWIFT—the main system banks use to coordinate international payments. And some $280 billion worth of Russian assets remain frozen in European banks.

Despite this, Russia’s war continues. The Russian economy grew at a rate of around 4 percent in the second quarter of 2024, down from a first quarter high of 5.4 percent. And despite predictions that the Russian military would suffer crippling shortages, Putin’s war machine has proved surprisingly efficient at rearming itself. In fact, the Russian arms industry is booming. The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a UK defence think tank, estimates that Russia’s domestic production of Kh-101 cruise missiles has increased eightfold over the last year. And Russian military spokespeople have boasted of supply lines that deliver tanks, drones, and artillery shells in their thousands.

Though the Russian boasts are surely hyperbole, Russia’s military resilience continues to embarrass the world’s economists. Shortly after Russian troops crossed the border into Ukraine, the International Monetary Fund predicted that the sanctions would cause Russian GDP to shrink by more than a tenth by the end of 2023. The Economist speculated about the possibility of a coup. Analysts at Reuters opined that Russia would probably collapse under such financial pressures. How then, has the Russian war machine kept on rolling?

The answer is that trade flows of restricted goods have shifted in response to the global sanctions. Those European technology companies, for example, that were previously Russia’s biggest suppliers, are now banned from supplying Russian customers. They have not, however, been banned from selling their wares to countries like Kazakhstan—where a once tiny tech industry is enjoying an unprecedented boom. The value of Kazakh tech exports has skyrocketed from $50m in 2020 to more than $500m in 2023. Much of this increase can be attributed to a rise in Russian business: tech exports to Russia have increased sevenfold since 2021—and this boost in trade has resulted from an increase in imports from exactly the same countries that have vowed not to do business with Russian clients. Kazakhstan now imports around €6.6 billion more from Europe than it did in 2021.

Yet, Kazakhstan is not the only nation acting as a middleman in Russia’s war economy. Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey—together with most of Central Asia— have become a porous borderland through which European goods can be funnelled into Russian hands. The region now imports €46 billion worth of extra goods from the EU, compared to 2021. That amounts to around three-quarters of the European imports Russia has lost out on since the start of the war. And crucially, the biggest boosts in trade have been in the products facing the heaviest restrictions. Armenia, for instance, imported twice as many chemicals, four times as much machinery, and four times as many electronic goods—all product categories under heavy sanctions—from Europe in 2023 than it did in 2021. As Alexander Kolyandr, of the Centre for European Policy Analysis has explained, through this multi-tiered system, landlocked Kyrgyzstan has started “importing half a million euros worth of naval navigation every month, on average.” These circuitous trade routes have enabled Russia to keep its military relatively well supplied with hardware. And according to the Royal United Services Institute, counterfeit Western tech continues to play a vital role in Russia’s high-end weapons.

The simplest way to address this problem would be to implement secondary sanctions that target the nations facilitating Russian trade. US President Joe Biden has announced that he plans to take action against foreign financial institutions that are doing business with Russia’s military-industrial complex. This policy has already had some success. Bloomberg reports that at least two Chinese banks have now stopped taking Russian payment for forbidden items.

There are, however, issues with such a strategy. First, it risks clogging up trade flows of civilian goods. The most recent round of EU sanctions, for example, not only bans firms from exporting semiconductors and drones to Russia, but ball bearings (which have civilian as well as military uses) and microwave ovens. What is more problematic, however, is that this approach risks abandoning third countries to dependence on regional autocrats. Places like Georgia are not natural allies of Putin. But cut off from Western economies, such countries may be dragged further into his orbit—and into that of autocracy more generally.

The sanctions may slow supplies of military components in the short term, but result in a global game of whack-a-mole wherein Western policymakers have to continually alter their sanctions to respond to ever changing trade routes. And in the long-term, such an approach risks undermining the West’s dominant position in the global economy. Autocracies like China, Russia, and Iran have long sought to establish payment systems and trading blocs outside Western influence. So far, these networks have failed to undermine the primacy of the dollar-based financial system from which the US draws its superpower status. But for the first time last year, more of China’s cross-border payments were conducted in yuan than in dollars. Most of the world’s population lives in countries that decline to enforce Western sanctions. Any attempt to strongarm these nations into following America’s lead risks alienating them entirely and further undermining an already fragile liberal world order.

The alternative is to offer the countries in Russia’s orbit Western support. Armenian trade with Russia has begun to slow since the EU awarded it some €270 million worth of monetary aid. But Russia has decades of experience at flouting Western financial rules, and is adept at funnelling its money through hidden channels, and offering lucrative trade deals to its shady partners.

This is most obvious in the oil industry. Here, Russia’s problem is not what it can buy, but what it can sell. Sanctions limiting the purchase of Russian oil initially caused a fall in the country’s energy exports, encouraging more excitable analysts to make bold predictions of Russia’s impending collapse. But, as commentators at Re: Russia have noted, Russia now brings in upwards of $60 billion more in exports (mostly oil and gas) than it did in the 10 years prior to the invasion of Ukraine. That is almost enough to finance Putin’s war, the costs of which are running at around $100 billion per annum.

Crucially, Russia has only been able to maintain the flow of oil thanks to a thriving shadow industry first tested by Iranian mullahs and Venezuelan oil cartels. Since Russia crossed the Ukrainian border, for example, the second-hand tanker market has grown exponentially. The smaller “Aframax” and “Suezmax” ships—the only ones that can fit into snug Russian ports—now fetch the same price as ships roughly twice their size did in 2022. These ramshackle freighters sail to private ports around the world, with their transponders switched off. They are renamed and repainted, often mid-voyage, to circumvent monitoring agencies. And they deliver illicit Russian oil to traders in India, Turkey, and the UAE—many of whom have only recently set up shop in so-called “free zones” meant to tempt businesses with a lack of red tape. Western officials suspect many of these to be fronts for Russian firms under sanction. In busy terminals, their crude is blended with that of others before being refined and sold on—sometimes to European customers.

The West is learning the hard way just how difficult it is to apply effective sanctions to a large, economically developed adversary. Strangling small, regional economies like those of Iran and North Korea is one thing. But suffocating an economy as large as Russia’s is another game entirely. This is a lesson that should have been learnt in the 1930s—when, as historian Nicholas Mulder points out, the fear of international sanctions was one of the factors that allowed autarchy to flourish in Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. But Western powers continue to view sanctions against Russia as a cheap alternative to military support for Ukraine. This is a dangerous illusion. Direct military and financial aid is the only way to help Ukraine achieve the victories that will be necessary to bring Putin to the negotiating table.

This is not to say that sanctions are worthless. Even leaky sanction regimes require complicated supply lines to outmanoeuvre—supply lines that are invariably more volatile and expensive for the Russian war machine than they would otherwise be. More could certainly be done to punish Russia economically—by, for example, tackling the off-shore tax havens and the anonymously owned shell companies that operate out of them, where the world’s autocrats and criminals stash their money. And more could—and should—be done to make use of the frozen assets of Russian oligarchs and of the Russian central bank. This is, after, already stolen money. It is true that such a move could undermine trust in the Western financial system—and push autocratic allies, particularly from the Gulf states, to shift their capital out of Western markets. That might hurt business in the short term. But it was the West’s embrace of Russian blood money that helped paved the way to Putin’s war.

Despite claims from Putin’s apologists that America and its European allies have spent decades antagonising his regime, Western powers have had a longstanding amnesty with Russia. When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, for example, it was Russian investments in European capitals that slowed the implementation of what turned out to be a largely ineffective programme of sanctions. There was then—as there was when Putin butchered civilians in Chechnya and Syria—a belief that Russia’s aggression could be contained, or at least directed somewhere beyond Western attention. But this logic was influenced, in no small part, by the long-running flow of Russian blood money into Western markets.

This dates back to at least the 1950s, when Soviet politicians realised that the resource wealth they had stolen from the people of the USSR was best kept in US dollars. And it’s a business model enthusiastically embraced by the City of London, which laundered around £100 billion every year for clandestine customers, thus exposing Western nations to Russian influence. Swiss banks are thought to hold over $200 billion in stashed Russian cash. Russians with links to the Kremlin hold at least £1.5 billion worth of UK property—at a conservative estimate. The true number is likely to be much higher, because there are almost 90,000 other properties held by opaque shell companies with unknown—and unknowable—owners.

This property empire exists only because, as Tom Burgis has pointed out, Western accountants, lawyers, and politicians accept hefty sums to help Russia’s oligarchs navigate the complex world of financial regulations, libel laws, and lobby groups. Tony Blair’s consultancy, for example, received $13 million from a Kazakh president—following his supposed 95% electoral victory—who was looking to repair his reputation after his security forces shot 15 oil workers dead for the crime of protesting for fair pay. Britain’s high-street banks have made millions processing money laundered by Russian oligarchs. Nobody wants to upset their clients. The money that flows from Putin’s allies into the white-collar West has created a dependency that for a long time prevented outright confrontation with Putinism.

Ironically, it is this patronage that helped Putin establish his grip on power by offering generational wealth to the oligarchs and privateers willing to act as enforcers for his regime. Yevgeny Prigozhin is a prime example of these. A hot-dog seller turned state-sponsored caterer, the Wagner leader was known as “Putin’s chef” before he rose to head up Russia’s flagship mercenary outfit. Multi-million-pound payments from Putinistas like Oleg Deripaska—head of EN+, the mining company that funnels the mineral wealth of Russia into private hands—to Greg Barker, a life peer in the House of Lords, make clear this nefarious chain of influence.

Sanctions and financial ostracisation are one way to exorcise this corrosive influence. They are steps in the right direction. But Putin’s fascist expansionism cannot be defeated by financial measures alone. Military aid may be expensive, but if we allow Ukraine to fall, other European democracies could be next in line.