Art

The Totalitarian Artist: Politics vs Beauty

After Duchamp, the art world came to view the pursuit of beauty as naïve and gravitated toward political art in their search for meaning. But this is a Faustian bargain: you can have meaning, but you do not get to make it for yourself.

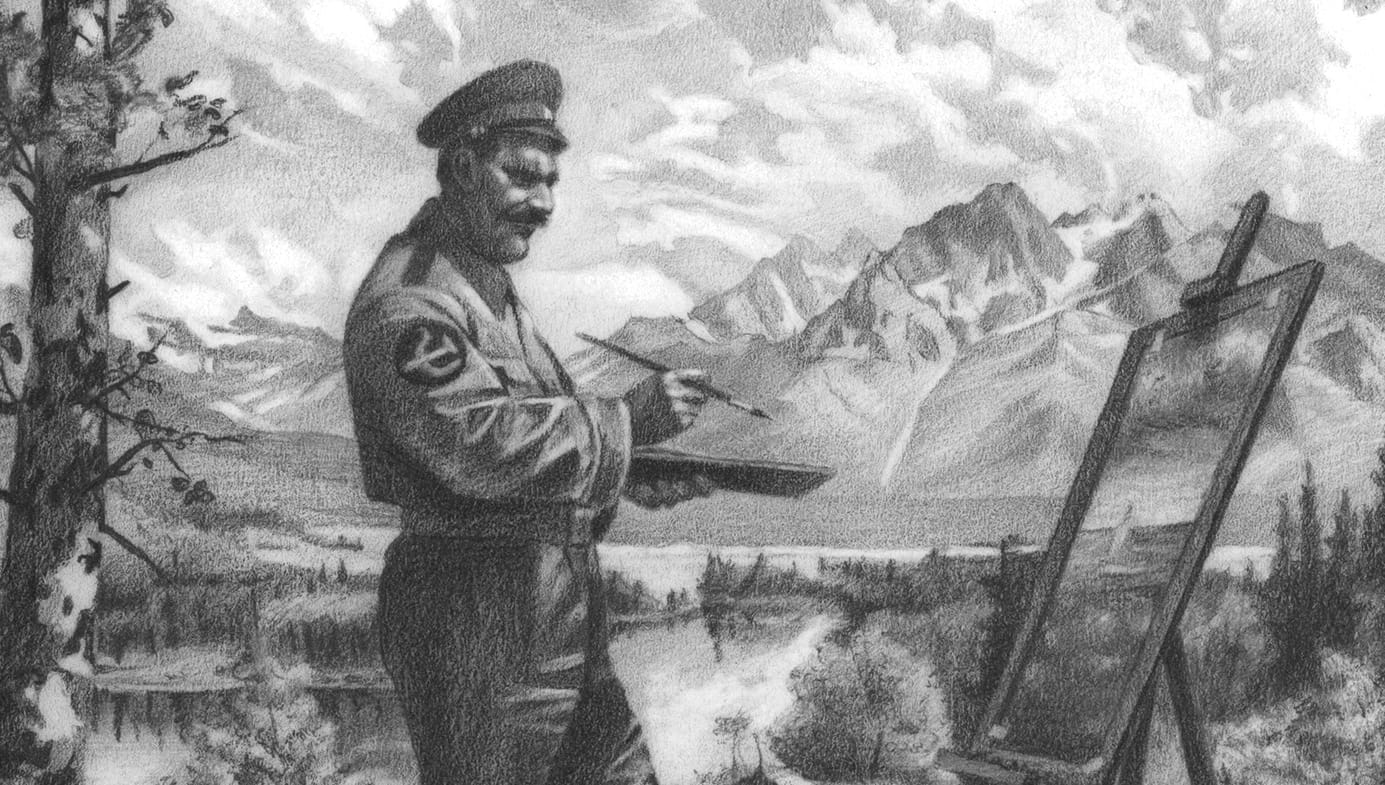

Hitler became the butt of a joke: a failed artist with a funny moustache. But we rarely ask ourselves whether there is an equivalent example of a leftist whose totalitarian personality emerged, in part, because the world shrugged at his bid for creative genius.

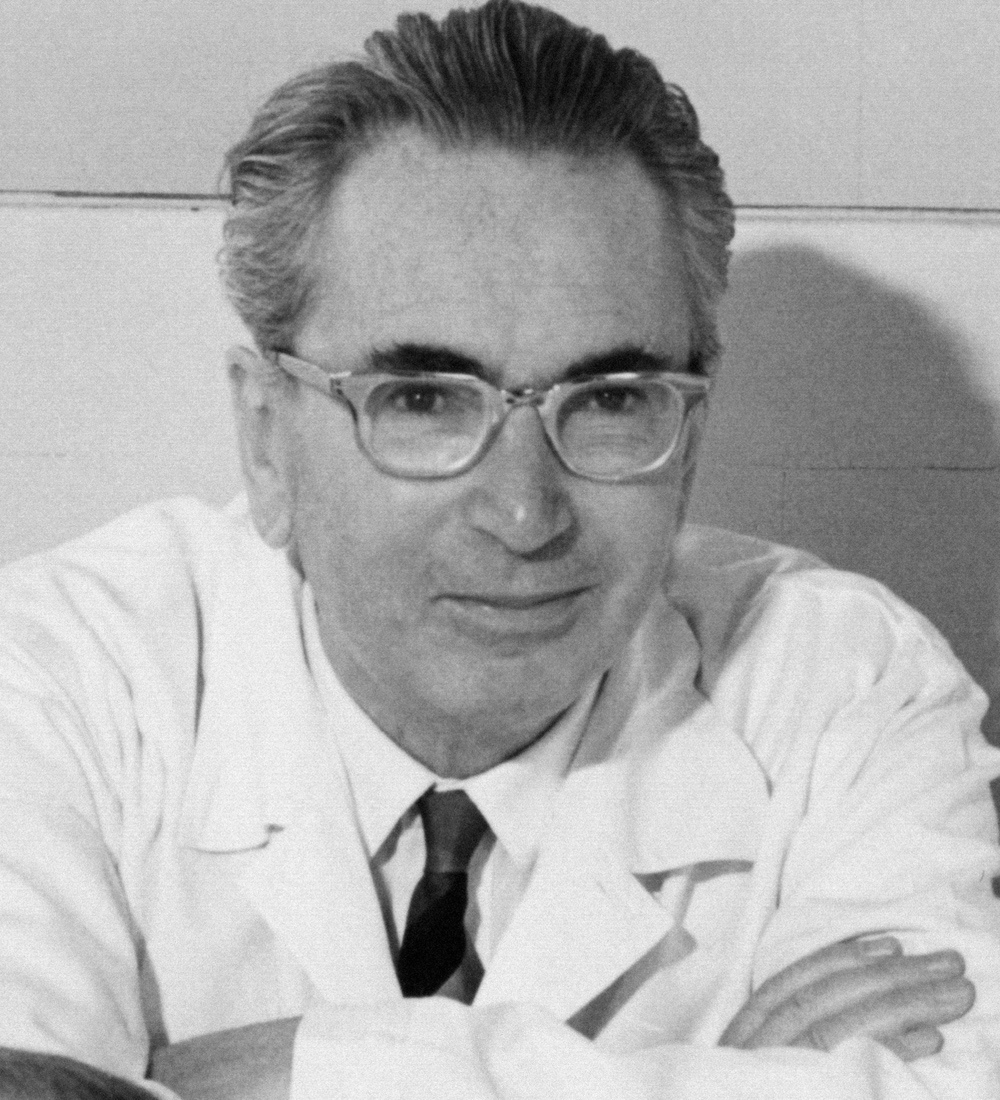

This was no idle question for Eric Hoffer, a philosopher of totalitarianism who helped shape the worldview of American presidents like Dwight D. Eisenhower, Lyndon Johnson, and Ronald Reagan, who awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He saw the totalitarian impulse as a temptation for failed artists of every political persuasion. In his 1951 book The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, he writes:

The man who wants to write a great book, paint a great picture, create an architectural masterpiece, become a great scientist, and knows that never in all eternity will he be able to realize this, his innermost desire, can find no peace in a stable social order—old or new. He sees his life as irrevocably spoiled and the world as perpetually out of joint.

Such a man often becomes, writes Hoffer, a “true believer,” a fanatic who is likely to embrace a revolutionary movement, since his personal frustration leads him to yearn for radical societal change. “All mass movements,” Hoffer argues, “draw their adherents from the same types of humanity and appeal to the same types of mind”:

A Saul turning into Paul is neither a rarity nor a miracle. In our day, each proselytizing mass movement seems to regard the zealous adherents of its antagonist as its own potential converts. Hitler looked on the German Communists as potential National Socialists: “The petit bourgeois Social-Democrat and the trade-union boss will never make a National Socialist, but the Communist always will.” Captain Röhm boasted that he could turn the reddest Communist into a glowing nationalist in four weeks. On the other hand, Karl Radek looked on the Nazi Brown Shirts (S.A.) as a reserve for future Communist recruits.

That the true believer can readily swap out Hitler for Stalin, or vice versa, explains historical curiosities like early twentieth-century Futurism—an art movement that celebrated the speed and dynamism of technology, industrialisation, and war—whose adherents were passionate fascists in Italy but communists in Russia. This is why artists of every political persuasion should heed the cautionary tale of Hitler’s frustrated artistic dreams.

Hoffer was particularly wary of “those with an unfulfilled craving for creative work” because they are “the most incurably frustrated”:

Both those who try to write, paint, compose, etcetera, and fail decisively, and those who after tasting the elation of creativeness feel a drying up of the creative flow within and know that never again will they produce aught worth-while, are alike in the grip of a desperate passion. Neither fame nor power nor riches nor even monumental achievements in other fields can still their hunger. Even the wholehearted dedication to a holy cause does not always cure them. Their unappeased hunger persists, and they are likely to become the most violent extremists in the service of their holy cause.

What should artists make of Hoffer’s special attention? The True Believer is a classic in the literature on totalitarianism, written by a celebrated thinker whom some have called a genius. Artists cannot simply ignore his charge that our failures are uniquely volatile threats to the social order.

To be sure, few failed artists have the chops to seize dictatorial power. But scores of progressive ideologues have been struggling to “make it” in the arts and have increasingly treated the creative realm as merely a way to further their holy cause. Over the years, Quillette has published a number of essays that document the ways in which ideology has compromised art. Taken together, these essays form a picture of the totalitarian artist.

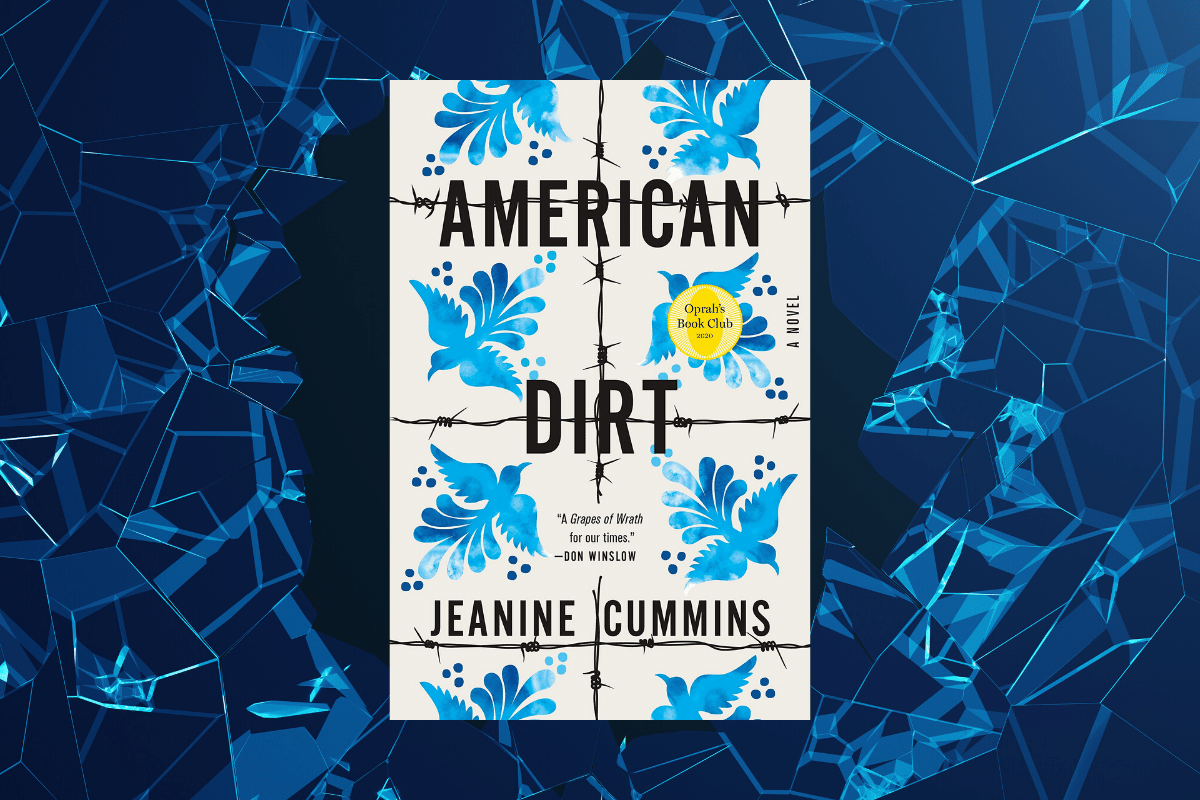

“How is art meant to happen when everyone is supposed to be thinking the same thoughts?” wonders novelist Seth Greenland in “The Balkanization of Art.” He bemoans our dogmatic cultural milieu in which the arts are “meant to serve a specific moral or didactic purpose.” In particular, Greenland laments the fact that the artist’s identity constrains the work he or she is allowed to produce:

In an unwritten cultural fiat, writers are granted “standing,” as in an author does, or does not have the “standing” (or, is allowed) to tell a particular story… Chinese-American author Amelie Wen Zhao postponed publication of her novel Blood Heir when she was accused of racism for writing insensitively about slavery (in a fantasy novel!). Award-winning author Kristine Kathryn Rusch decided to self-publish her novels about a black detective because of the degree to which she, as a white woman, was discouraged by traditional publishers from writing about a black character.

This precept applies across art disciplines:

The same problem roiled the art world at the Whitney Biennial of 2017, at which the artist Dana Schutz had the temerity to exhibit a painting of Emmitt Till. Till was a black teenager lynched in Mississippi after he was falsely accused of whistling at a white woman. His death was a tragedy for the entire nation. Schutz’s powerful canvas depicts the slain boy in his coffin. The painting was unveiled; an uproar followed. The Internet predictably vituperated. Protesters linked arms in front of the work to impede the view of museum-goers. Schutz’s crime? Creating this undeniably potent work of art while being a member of the wrong race.

This deference to identity politics is an example of Hoffer’s observation that the true believer “subordinates creative work to the advancement of the movement”:

The true-believing artist does not create to express himself, or to save his soul, or to discover the true and the beautiful. His task, as he sees it, is to warn, to advise, to urge, to glorify and to denounce.

The idea that politics must have a mandate over art seems self-evident to many contemporary art students—including many young hopefuls destined to shrivel into Hoffer’s “incurably frustrated.” When they begin to learn art history, students are typically given Janson’s History of Art. About fifteen years ago, I was assigned the seventh edition, which culminates in a chapter on postmodernism that largely focuses on politics. My classmates and I dutifully tried to pick up where history left off by making political art of our own. I had long since come to my senses by the time I returned to the classroom as a university lecturer—but I was still asked to teach students how to make “socially-engaged art.”

Students often perceive the history of art as a progression towards the evolution of ever more political art. And it’s no wonder. In Janson’s final chapter—his parting note about the cutting edge of art—the textbook concludes:

At the heart of European Postmodernism is the premise that all literature and art is an elaborate construction of signs, and that the meaning of these signs is determined by their context. … Context can change as viewers bring their personal experiences to the work. Postmodernists claimed there can be no fixed meaning, and thus no fixed truth. By the late 1970s, artists and critics had digested this theory and applied it to art. Postmodern theory now became the driving force behind much art making and criticism. …

Now a large number of artists and critics asked more overtly and persistently: How do signs acquire meaning? What is the message? Who originates it? What—and whose—purpose does it serve? Who is the audience and what does this tell us about the message? Who controls the media—and for whom? … Now scholars approached art from countless angles, using issues of gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, economics, and politics to demonstrate the many layers of meaning and ideas embedded in a work of art.

But these “countless angles” all happen to point in the same direction—towards progressive politics. The philosophical idea that there is “no fixed meaning, and thus no fixed truths” is instrumental to an identity politics that posits subjective experience as the paramount authority. Despite all the postmodern talk about “no fixed truth,” for critics and teachers who follow this line of thinking, there are certainly right and wrong answers to the questions they ask—and students are often afraid to give the wrong ones.

Velvet Favretto describes what it is like to be such a student in her 2018 essay, “Postmodernism and the Decline of the Liberal Arts.” She takes issue with those who “embraced a postmodern viewpoint” yet “tend to harshly ostracise any conflicting perspective, thereby eroding the intellectual freedom upon which the liberal arts had hitherto relied.” And she shares an anecdote about her experience at university that will resonate with any art student not on the political Left:

liberal arts students are taught that all interpretations are valid, and that disapproval of any idea is evidence of their own narrow-mindedness. This presents a paradox: on the one hand, we are instructed to be inclusive and indulge every student’s subjective experience, regardless of whether it is right or wrong because objective judgments about what is right and wrong don’t exist. On the other hand, this suggests that anyone who does believe in the existence of an objective right and wrong are, themselves, objectively wrong. Inconsistencies like this are often evident in everyday classroom interactions. One of my humanities lecturers, for example, in attempting to explain the complexity of identity, condemned the idea that people should dictate what other people think, and “make anyone who departs from that way of thinking feel fearful and different.” She seemed unaware that the course she teaches is saturated with cultural and political biases that exclude any student who holds differing views. Such is the devious nature of postmodernism in the modern classroom—the ‘tolerance’ only extends to those who conform.

Our propagandistic moralisers have reinvented the spirit of 1930s Social Realism, which also valorised identity by glorifying the working man. Then, as now, the art world demonstrated its fealty to progressive politics. By Tom Wolfe’s account, political art was even more dominant during the 1930s than today:

For more than ten years, from about 1930 to 1941, the artists themselves, in Europe and America, suspended the Modern movement … for the duration, as it were … They called it off! They suddenly returned to “literary” realism of the most obvious sort, a genre known as Social Realism.

Left politics did that for them. Left politicians said, in effect: You artists claim to be dedicated to an anti-bourgeois life. Well, the hour has now come to stop merely posing and to take action, to turn your art into a weapon. Translation: propaganda paintings. The influence of Left politics was so strong within the art world during the 1930s that Social Realism became not a style of the period but the style of the period. Even the most dedicated Modernists were intimidated. Years later Barnett Newman wrote that the “shouting dogmatists, Marxists, Leninists, Stalinists, and Trotskyites” created “an intellectual prison that locked one in tight.” I detect considerable amnesia today on this point. All best forgotten! Artists whose names exist as little more than footnotes today—William Gropper, Ben Shahn, Jack Levine—were giants as long as the martial music of the mimeograph machines rolled on in a thousand Protest Committee rooms. For any prominent critic of the time to have written off Ben Shahn as a commercial illustrator, as Barbara Rose did recently, would have touched off a brawl. Today no one cares, for Social Realism evaporated with the political atmosphere that generated it.

Albert Camus also disapproved. In a review of his rereleased 1957 speech “Create Dangerously: The Power and Responsibility of the Artist,” Clint Margrave discusses Camus’ opinion of Social Realism:

He sees it as an art with an agenda that destroys the freedom of the artist, and contributes little to art in the false way it depicts reality. Because its focus is idealistic, not realistic, it inevitably ends up as propaganda with “good and evil people,” sacrificing art for what the artist believes is the superior goal of social justice:

“In sum, it temporarily suppresses art so it may first support justice. When justice exists, in a future that is still unknown, art will be reborn…”

Today, pressure may be put on artists to toe the line ideologically in their art at the risk of social and career suicide. This type of pressure can intimidate artists to no longer work in the pursuit of truth, but rather for the “good” of society (which in fact, does not accomplish what it intends). It can discourage artists from exploring taboo subjects and become one of the biggest threats to their freedom. For Camus, art seeks to understand, not to judge, and the best works end up, “baffling all judges.” The role of the artist is not as a “preacher of virtue”:

“What writer would from now on in good conscience dare set himself up as a preacher of virtue? For myself, I must state once more that I am not of this kind. I have never been able to renounce the light, the pleasure of being, and the freedom in which I grew up. But although this nostalgia explains many of my errors and my faults, it has doubtless helped me toward a better understanding of my craft.”

Camus was not a true believer. He cherished freedom too much—and, as Hoffer writes, “Freedom aggravates at least as much as it alleviates frustration. Freedom of choice places the whole blame of failure on the shoulders of the individual.” The true believer flinches from freedom because “Unless a man has the talents to make something of himself, freedom is an irksome burden. Of what avail is freedom to choose if the self be ineffectual?” Art with an agenda is the antithesis of artistic freedom but it is an attractive prospect for some—because making propaganda provides an easy lift for the failed artist.

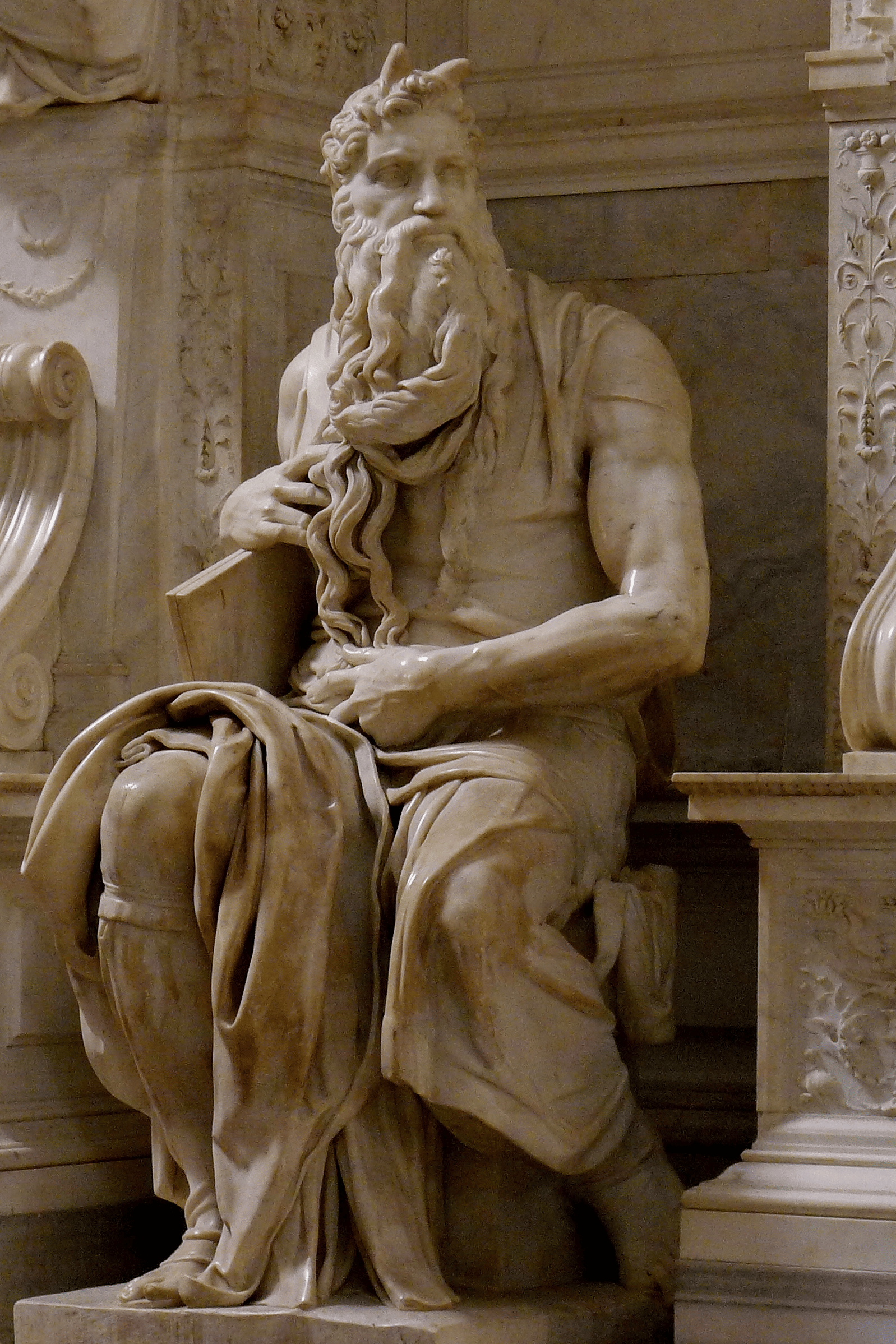

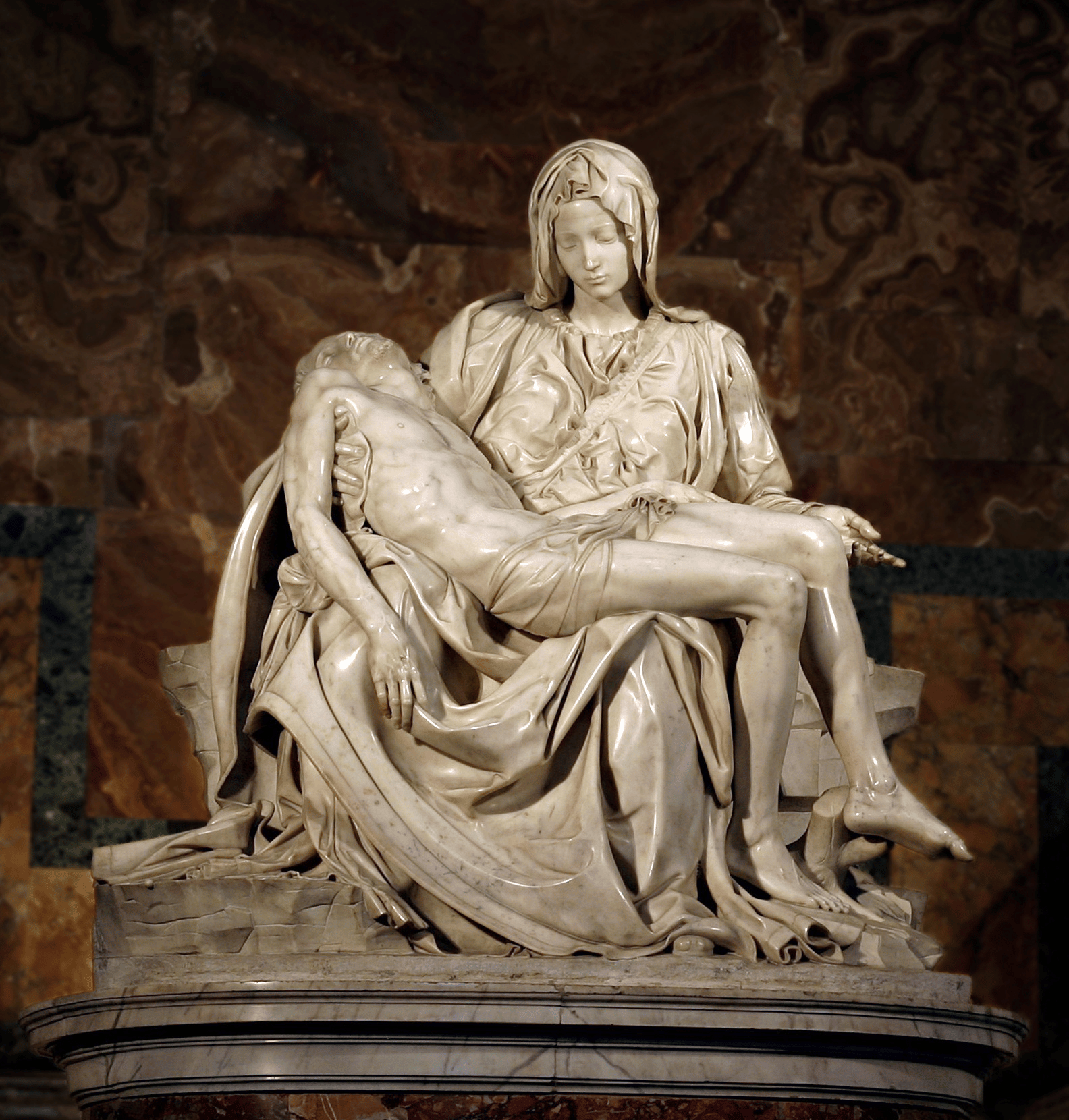

For over a century now, leftist politics has been ascendant in the art world, though its stridency waxes and wanes. But art has always been pressed into service by ideologies, usually religious. Historically, artists inspired by religious doctrines have produced marvels, as when the Renaissance blossomed in Catholic cities like Florence and Rome, and the Pope commissioned Michelangelo to strain against the limits of human achievement. Clearly, if ideology is to threaten art, then it is not enough for that ideology to hold power—it must also be fanatical.

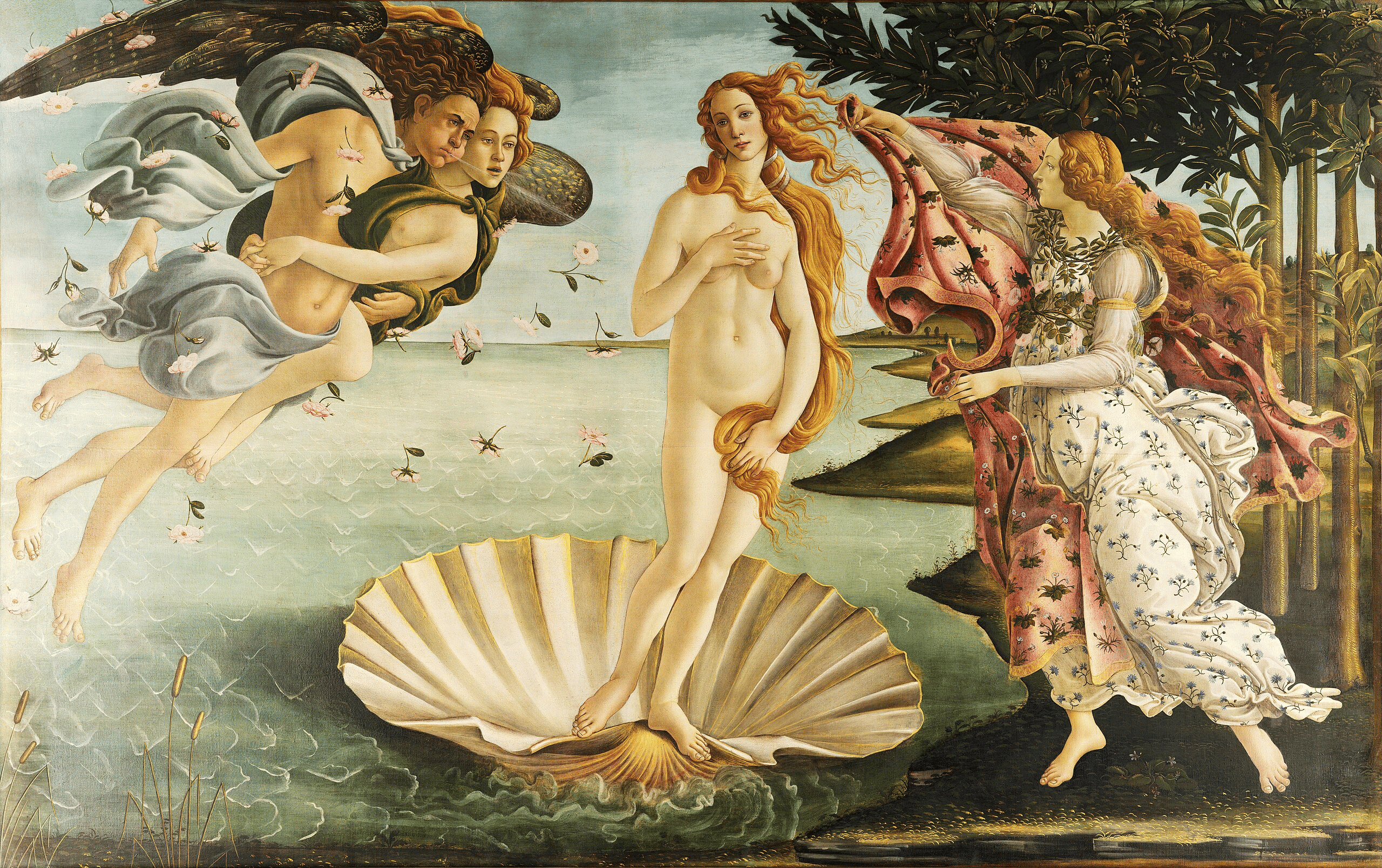

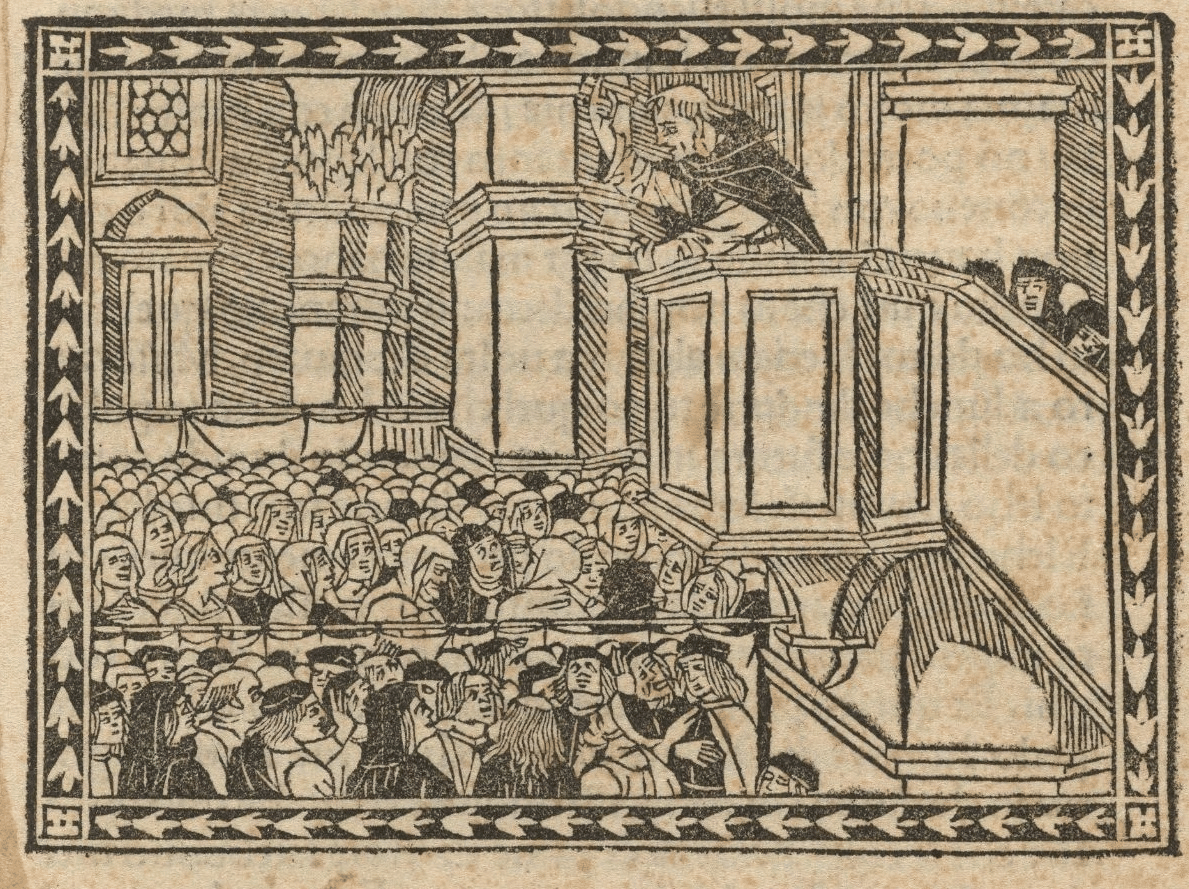

Compare Michelangelo to his contemporary Sandro Botticelli, who fell under the spell of Girolamo Savonarola and his fringe interpretation of Catholicism. The Dominican friar was notorious for his “bonfires of the vanities,” at which fanatics would burn secular art and luxury goods in the squares of Renaissance Florence. When Botticelli became a true believer in Savonarola’s movement, he is thought to have felt compelled to torch some of his own insufficiently Christian paintings—an incalculable loss to humanity.

Giorgio Vasari (1511–74) is often considered “the first art historian.” He was born the year after Botticelli’s death. In his chapter on Botticelli in The Lives of the Artists, Vasari writes:

He was apparently a follower of Savonarola’s faction, which led him to abandon painting; unable to make enough to live on, he fell into the direst of straits. Nevertheless, he obstinately remained a member of this faction and became a piagnone (as they were called in those days), which kept him away from his work. Thus he eventually found himself both old and poor, and if Lorenzo de'Medici (for whom Sandro, among many other projects, had done a great deal of work at the Villa dello Spedaletto in Volterra), along with his friends and other prominent men who were admirers of his talent, had not assisted him financially during the rest of his life, he would almost have starved to death.

The piagnoni—“the weepers”—cried because the world is full of sin. They burned any possessions that they loved more than God. How Botticelli must have loved his paintings!

In fifteenth-century Italy, men of God commanded artists. But the Pope presided over the status quo that governed Botticelli’s life in Florence, whereas Savonarola was an apocalyptic cult leader who agitated against it. By that point in time and space, standard-issue Catholicism was no longer fanatical. The difference between the Pope and the friar was that the latter desired change. As Hoffer notes, “A revolutionary movement is a conspicuous instrument of change,” and failure causes some to crave this:

It is understandable that those who fail should incline to blame the world for their failure. The remarkable thing is that the successful, too, however much they pride themselves on their foresight, fortitude, thrift, and other “sterling qualities,” are at bottom convinced that their success is the result of a fortuitous combination of circumstances. The self-confidence of even the consistently successful is never absolute. They are never sure that they know all the ingredients which go into the making of their success. The outside world seems to them a precariously balanced mechanism, and so long as it ticks in their favor they are afraid to tinker with it. Thus the resistance to change and the ardent desire for it spring from the same conviction, and the one can be as vehement as the other.

Hoffer singles out creative failure for its potency in driving people to seek revolutionary change:

Nothing so bolsters our self-confidence and reconciles us with ourselves as the continuous ability to create; to see things grow and develop under our hand, day in, day out…. It is impressive to observe how with a fading of the individual’s creative powers there appears a pronounced inclination toward joining a mass movement. Here the connection between the escape from an ineffectual self and a responsiveness to mass movements is very clear. The slipping author, artist, scientist—slipping because of a drying-up of the creative flow within—drifts sooner or later into the camps of ardent patriots, race mongers, uplift promoters and champions of holy causes.

Did Botticelli feel “a drying-up of the creative flow within”? Vasari only tells us that he “wasted” his time illustrating Dante’s Inferno—a project that he never completed. Did the early stages of artistic failure drive him into Savonarola’s fold, or was his creative flow dammed up by the friar’s withering sermons?

Hoffer summarises the history of the way in which mass movements have stifled creativity:

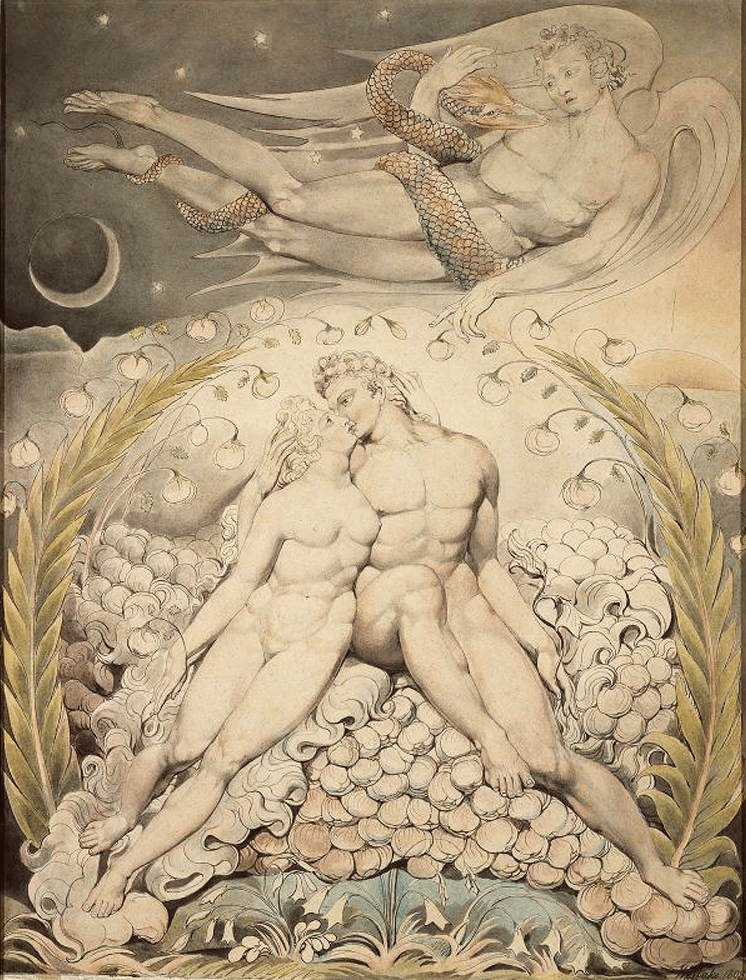

Trotsky knew that “Periods of high tension in social passions leave little room for contemplation and reflection. All the muses—even the plebeian muse of journalism in spite of her sturdy hips—have hard sledding in times of revolution.” On the other hand, Napoleon and Hitler were mortified by the anemic quality of the literature and art produced in their heroic age and clamored for masterpieces which would be worthy of the mighty deeds of the times. They had not an inkling that the atmosphere of an active movement cripples or stifles the creative spirit. Milton, who in 1640 was a poet of great promise, with a draft of Paradise Lost in his pocket, spent twenty sterile years of pamphlet writing while he was up to his neck in the “sea of noises and hoarse disputes” which was the Puritan Revolution. With the Revolution dead and himself in disgrace, he produced Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, and Samson Agonistes.

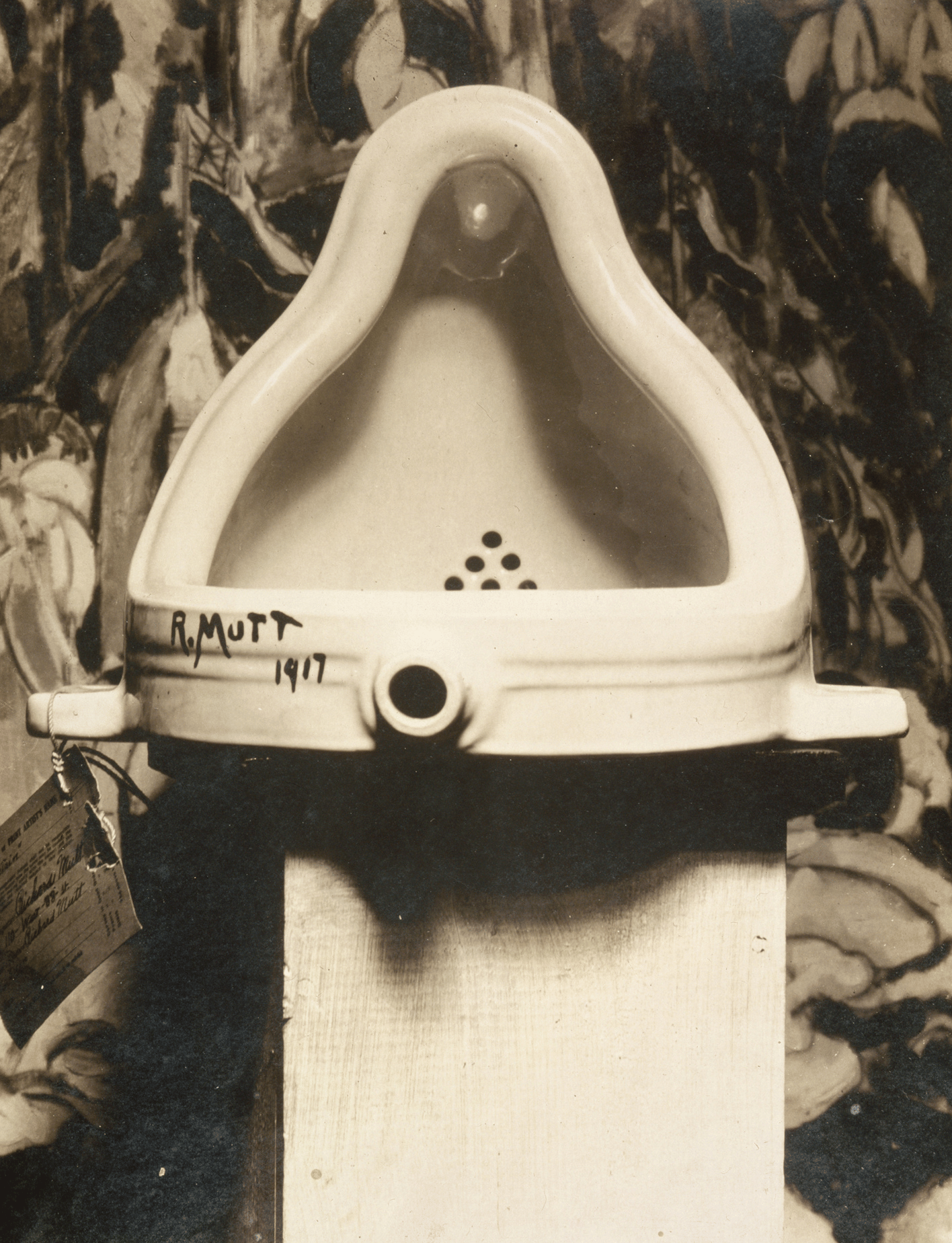

Totalitarian ideas suppress an artist’s capacity to create beauty. This tendency crystalised in the early twentieth century when Marcel Duchamp, the father of contemporary art, presented a urinal as an artwork. In doing so, he fixed an idea in the art world like a cuckoo laying its egg in another bird’s clutch. And just as the baby cuckoo, once hatched, pushes its adopted siblings out of their nest, his idea pushed out concepts like truth and beauty like so many doomed baby birds. Duchamp himself implicitly acknowledged this when he called his project “anti-art.”

Duchamp made “anti-art” to disabuse artists of their ancient raison d’être—beauty, and the skill necessary to bring it forth into the world. Dismissing nearly all art as “retinal,” that is, as superficial because it was intended only to please the eye, he instead wanted “to put art back in the service of the mind.” Declaring that “Anything is art if an artist says it is,” Duchamp used his Fountain to insist on this point—to prove that he meant it when he claimed that literally anything can be art. Many artists emerging from the meat grinder of World War I were receptive to Duchamp’s aesthetic nihilism. But theirs was hardly a virtuous response to evil, as Jason Newman insists in “Why Postmodern Art is Vacant”:

A nonsense has dominated modern art theory (insomuch as there is a theory) that, after the horrors of two World Wars, a return to conveying the beautiful, the sublime, and the transcendent would be fruitless, unfeeling, and in some way would serve to whitewash history. As Theodore Adorno, one of the most prominent cultural critics of the Frankfurt school, declared, “Writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.”

This is piffle. It is true that nothing could match the scale of the Holocaust for organised brutality or the Somme for mindless loss of life. However, the Renaissance saw large scale wars across Italy and Europe between warring kingdoms and city states, disease was widespread, and poverty was grinding. Yet in the midst of all this horror and death Italy and Europe underwent a cultural flourishing that yielded some of the greatest artistic masterpieces man has ever created. Late gothic art produced glorious carvings, panel paintings, frescos, sculptures and manuscripts in the years after the black death swept through Europe killing between 75–200 million people in a mere seven years. To somehow suggest that Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus” is any less captivating or magnificent post-1945 or post-1918 than it was pre-1939 or pre-1914 is fatuous.

Adorno and likeminded artists lacked the moral fortitude of Holocaust victims like Auschwitz survivor Viktor Frankl, who recalls in his 1946 memoir Man’s Search for Meaning how prisoners would rush out of their huts to glimpse a sunset reflected in the puddles on the muddy ground and whisper to each other of their awe at the world’s capacity for beauty. Frankl relates how:

As the inner life of the prisoner tended to become more intense, he also experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before. Under their influence he sometimes even forgot his own frightful circumstances. If someone had seen our faces on the journey from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp as we beheld the mountains of Salzburg with their summits glowing in the sunset, through the little barred windows of the prison carriage, he would never have believed that those faces were the faces of men who had given up all hope of life and liberty. Despite that factor—or maybe because of it—we were carried away by nature’s beauty, which we had missed for so long.

While Duchamp and Adorno believed in casting beauty aside, in compounding the horror of war and genocide by bringing more ugliness into the world, Frankl believed in “loving dedication to the beautiful”:

Should I perhaps try to explain for you with some hackneyed phrase how and why experiencing beauty can make life meaningful? I prefer to confine myself to the following thought experiment: imagine that you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favorite symphony, and your favorite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine; and now imagine that it would be possible (something that is psychologically so impossible) for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would agree with me if I declared that in this case you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like: “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!”

No one standing before Duchamp’s urinal feels overwhelmed with emotion because that moment alone has imbued their life with meaning. But of course, Duchamp never meant it to—he said that he made anti-art “based on a reaction of visual indifference, with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste… in fact a complete anaesthesia.” Because even a talentless hack can easily select a random object that is visually indifferent, Duchamp thereby eliminated the need for artists. He was “stripping each human entity of its distinctness and autonomy and turning it into an anonymous particle with no will and no judgment of its own,” as Hoffer puts it. If Frankl had shared Duchamp’s indifference to beauty, then he would have probably died in the camps.

After Duchamp, the art world came to view the pursuit of meaning through beauty as naïve. So, another reason that artists gravitate toward political art is as a replacement for their search for meaning. A sincere and earnest young artist, who does not have it in her to put on airs of ironic detachment, still yearns to make meaningful work. Political art offers that option without any snickering. It is a Faustian bargain: you can have meaning, but you do not get to make it for yourself.

Newman picks apart the idea that “post-war ennui” was the driving motivation behind Duchamp’s Dadaist movement:

It is foolish to say that this breakdown in realism and art in general can be put down to the traumatic events of the first half of the 20th century. Something much more nuanced appears to have been at work. The Dadaists and those who thought like them went through and came out of the wars convinced that the old techniques and traditions were now redundant and to be thrown on the bonfire. They rejected the old ideas convinced that the world was forever in flux and that it was time to start anew in an era where this flux was to be embraced. Objectivity was no more. Everything and anything could now be considered art, and everything was as good as anything else.

Intriguingly, there is another movement that broadly mirrors the development of Dadaism: that of the Postmodernists, more specifically the ‘Frankfurt School.’ Like the Dadaists, their genesis was in the interwar years but also like the Dadaists their influence really only started to be felt in the post-War years. They too came out of the first half of the 20th century traumatised. They were appalled by the rise of fascism, but also crestfallen at the failure of Marxist-Leninism to deliver utopia. Having conducted a postmortem on Marxism, they formed their own new ideology, still heavily influenced by Marx but with a new emphasis on the cultural rather than the economic. Like the Dadaists, they also felt the old traditions should be thrown on the rubbish heap of history— faith, family, and the nation had to be destroyed. And, like the Dadaists, they were convinced the subjective was king and objective truth was dead.

This is the central problem: Too many artists are in thrall to the belief that objectivity is overrated. The rejection of objectivity upended our tradition of depicting the real world in a beautiful way. When painters sketch their subjects from observation, they are trying to see the real world so well that they can replicate its image. Drawing and painting are ways of understanding objective reality by looking hard at it. If you nix objectivity, then how can you justify keeping realism, and by what standard do you measure beauty?

But objectivity and standards of aesthetic beauty are the enemies of the failed artist. A lack of talent, practice, or imagination can be masked if the art world no longer prioritises such things and that may bring the failed artist some relief. But that relief may prove illusory if the artist makes a political misstep, fails to conform ideologically, or cannot skilfully manoeuvre her way through the inevitable popularity contests that emerge when artistic greatness is not determined by artistic skill.

Progressives are not the villains in this story. The true believer can vacillate between Hitler and Stalin, as the precise flavour of the favoured ideology matters less than the psychology that marks out the true believer. The art world does not have a totalitarian character because it is left wing—it has a totalitarian character because Duchamp made it a refuge for the failed artist.

In his article, Newman rounds up examples of the most transgressive art to uphold Duchamp’s legacy. Provocations like Chris Ofili’s mixed-media painting The Holy Virgin Mary, which features elephant dung and pornography, and Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit—which is literally just that in a can—continue Duchamp’s irreverent theme. But even postmodern artists sometimes produced emotionally powerful work, such as “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) by Félix González-Torres.

This conceptual piece debuted in New York City in 1987, the year in which González-Torres’s partner was diagnosed with AIDS. It is simply two commercial clocks installed on a wall side-by-side, touching. They were initially set to the same time but fell out of sync over the course of the exhibit. The artist ached to be with his lover forever even as one of their heartbeats began to falter, just as one of his clocks lost time before the other. The piece evokes the injustice of mortality, and specifically the plight of gay men suffering from both a frightening new disease and the opprobrium of people who blamed them for dying from it.

“Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) is quintessentially postmodern. Mass-produced rather than made by the artist’s hand, its meaning is meant to come only from González-Torres’s subjective experiences and ideas, or the interpretations that others place upon them after encountering his installation. Many fans of González-Torres cherish his work in the spirit of “the personal is political,” and much of his following consists of gay men who see themselves in his story. For those who appreciate his art, the fact that he lacks a sculptor’s skill is irrelevant. The concept behind “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) can stir your heart if you let it, but it is not necessary to see the actual artwork to get the point. In fact, seeing the physical object itself is almost beside the point.

I have never seen En el Aire by Teresa Margolles, but it may be my favourite conceptual art piece. In 2003, Margolles filled a museum with bubbles. Here is how someone who did see the artwork described it:

In the museum’s soaring hall children play under bubbles that come from Teresa Margolles’ piece En el Aire (In the Air, 2003). Running, laughing, catching, they are fascinated by the glistening, delicate forms that float down from the ceiling and break up on their skin. A common motif in art history, the bubble has long been used as a memento mori, a reminder of the transitory nature of life. The children’s parents, meanwhile, studiously read the captions. Suddenly, with a look of disgust, they come and steer their offspring away. The moment of naive pleasure turns into one of knowing repulsion: they have learned that the water comes from the Mexico City morgue, used to wash corpses before an autopsy. It’s unimportant that the water is disinfected; the stigma of death turns the beautiful into the horrific.

Artists have long used literal corpses to make something beautiful. They dissect them to study their anatomy, and they sketch them to observe the pallor and texture of dead skin. Théodore Géricault never could have painted the dead and dying shipwreck victims in The Raft of the Medusa without spending time at the morgue.

But despite the grotesque nature of their materials, Margolles and Géricault are not irreverent like Duchamp, Ofili, and Manzoni. On the contrary, Margolles gathers wash water only from victims of the drug trade that has ravaged her home in Culiacan, Mexico, and she is adamant that her intention is to make people share in her sorrow. Margolles and González-Torres get away with creating emotive art because their personal identities add so much to the meaning of their art works—but even if you can’t stand identity politics, “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) and En el Aire are sincere expressions of the human condition and so you may still find meaning in their concepts.

So, not all postmodern artists “contribute to the ugliness and desecration” that Newman laments. Sometimes artists sneak meaning back in. But even these touching examples disregard artistic skill. As Newman demands to know, “Where is the skill and ability in all this?”:

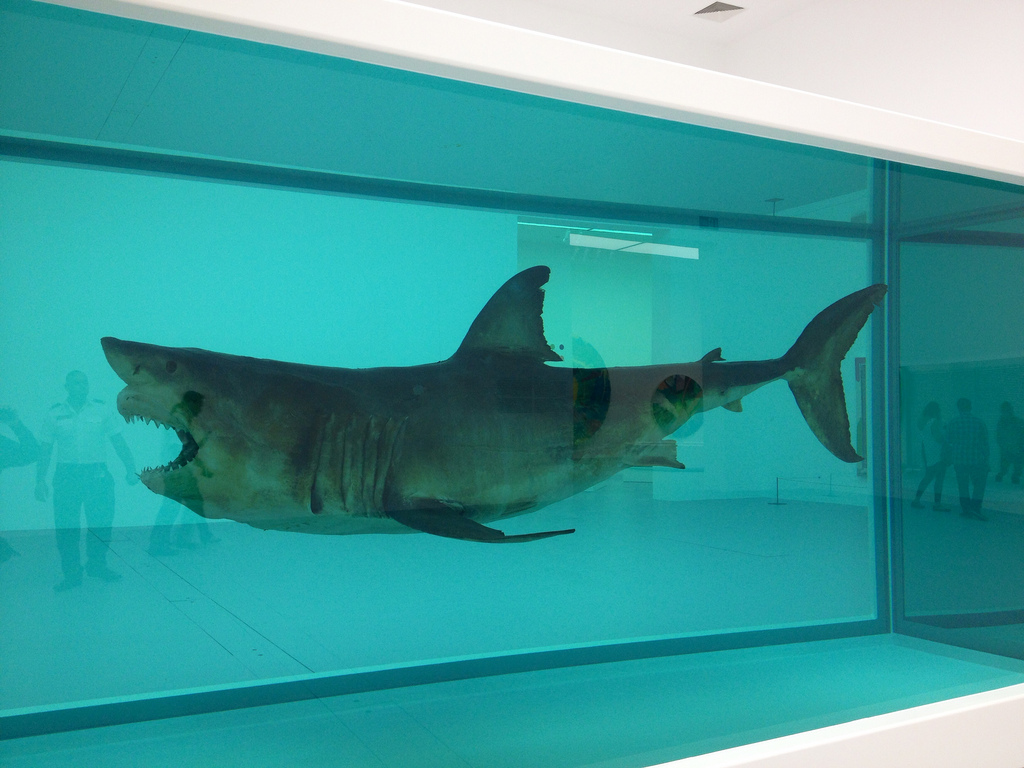

No skill is required to place a rotting cow’s head in a glass cube with an insect-o-cutor (A Thousand Years by Damien Hirst). No ability is needed to set up a room with a light that switches on and off (Work No. 227: The Lights Going On and Off by Martin Creed, a work that won him the Turner Prize). It is most probably the case that the electrician who installed said lights and the abattoir worker who severed the cow’s head possess more skill and expertise than either Mr Hirst or Mr Creed.

In a 2015 interview with the BBC about his forthcoming exhibition involving marble carvings, Hirst was confronted by the interviewer with the charge that he does not make many of his pieces. Hirst replied that: “to carve one of these structures takes two years, and it’s like, I haven’t got time to learn to carve. But I know exactly what I want, and I want it to look perfect and I can make it perfect using these guys” (referring to a team of sculptors he had employed). He finished by stating, “It’s never been a problem for me in art and I don’t think it’s a problem… I mean it’s amazing that we’re having this conversation really.”

Michelangelo’s Pieta, carved by his own hands, took two years to create and was the result of thousands of hours of anatomical study. Mr Hirst’s remark that he, “hasn’t got time to learn to carve” is symptomatic of what is wrong with modern art. His incredulity at having been asked such a question by a philistinic BBC interviewer is palpable. It is almost beneath him. Why should he—Damien Hirst, multi-millionaire darling of the art world!—waste his time doing something so trivial, so menial as actually crafting his creations?

Michelangelo’s skill can be judged by an objective standard: how well his sculptures and paintings resemble reality. Without objectivity, artists are no longer expected to achieve technical mastery. Many still do—but expertise has been so devalued that it is no longer a necessary qualification. And once expertise lost its lustre, the arts became fertile ground for true believers. The failed artists that Hoffer warned against have perfect camouflage in an art world that opposes standards of beauty.

But Hoffer’s views of art history in The True Believer are not all doom and gloom. Hoffer differentiates between the active phase of mass movements—that is, their rise to power, which Hoffer defines as “the phase molded and dominated by the true believer,” whose culture “is sterile,” and what happens next, once the active phase has ended. This is more encouraging for artists:

Whenever we find a period of genuine creativeness associated with a mass movement, it is almost always a period which either precedes or, more often, follows the active phase. Provided the active phase of the movement is not too long and does not involve excessive bloodletting and destruction, its termination, particularly when it is abrupt, often releases a burst of creativeness. This seems to be true both when the movement ends in triumph (as in the case of the Dutch Rebellion) or when it ends in defeat (as in the case of the Puritan Revolution). It is not the idealism and the fervor of the movement which are the cause of any cultural renascence which may follow it, but rather the abrupt relaxation of collective discipline and the liberation of the individual from the stifling atmosphere of blind faith and the disdain of his self and the present. Sometimes the craving to fill the void left by the lost or deserted holy cause becomes a creative impulse.

We are overdue for a renascence. About thirty years ago, the provocative art critic Dave Hickey declared beauty the “Issue of the Nineties,” protested that “nothing redeems but beauty,” and wondered “how, in the final two-thirds of the twentieth century, we have come to do without it.” The philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto discusses Hickey’s declaration in his 2003 book The Abuse of Beauty:

In 1993 when Hickey’s essay was published, art had gone through a period of intense politicization, the high point of which was the 1993 Whitney Biennial, in which nearly every work was a shrill effort to change American society. Hickey’s prediction did not precisely pan out. What happened was less the pursuit of beauty as such by artists than the pursuit of the idea of beauty, through a number of exhibitions and conferences, by critics and curators who, perhaps inspired by Hickey, thought it time to have another look at beauty.

In his introduction to The Abuse of Beauty, Danto admits that he initially “felt somewhat sheepish about writing on beauty” which “had almost entirely disappeared from artistic reality in the twentieth century, as if attractiveness was somehow a stigma, with its crass commercial implications.” But Danto came to understand the importance of beauty:

The spontaneous appearance of those moving improvised shrines everywhere in New York after the terrorist attack of September 11th, 2001, was evidence for me that the need for beauty in the extreme moments of life is deeply ingrained in the human framework. In any case I came to the view that in writing about beauty as a philosopher, I was addressing the deepest kind of issue there is…. But beauty is the only one of the aesthetic qualities that is also a value, like truth and goodness. It is not simply among the values we live by, but one of the values that defines what a fully human life means.

It took the single most brazen terrorist attack in history for a twenty-first-century philosopher of aesthetics to realise that beauty matters—and dare to say so in earnest, out loud. Danto was struck by what Frankl learned in the concentration camps. For Frankl shows us what Duchamp tried to take away from artists: the gift of generating meaning by summoning beauty into an often ugly world.

In Frankl’s thought experiment, he describes someone who believes that listening to a symphony makes life worth living—even with all the suffering that living demands of us. Now reflect on this story from the composer’s point of view: Imagine you can summon enough beauty to make someone want life, even a deeply tragic life, because “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!” Absorb the magnitude of Frankl’s exclamation: the torture and humiliation in Auschwitz was worth it just to hear your music. If we follow Duchamp and the postmodernist artists and reject beauty and meaning in art, then we rob the Holocaust survivor of a reason to live, and the artist of the honour of creating something worth living for.