Nations of Canada

Return of the Jesuits

In the 22nd instalment of ‘Nations of Canada,’ Greg Koabel describes how Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu used their nascent Quebec colony as a means to promote French global power and spread Christianity.

What follows is the twenty-second instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialised Quillette project adapted from Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name.

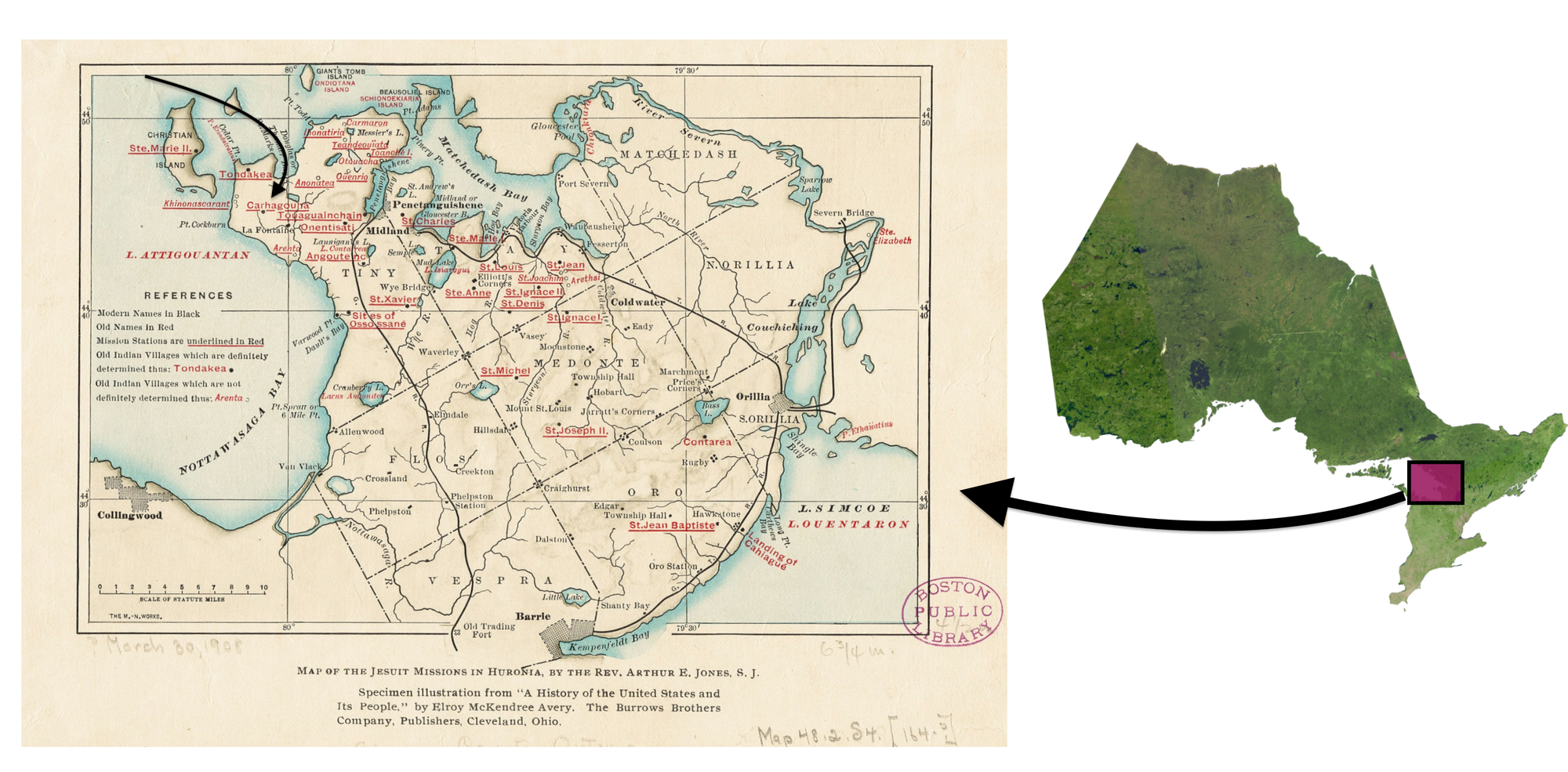

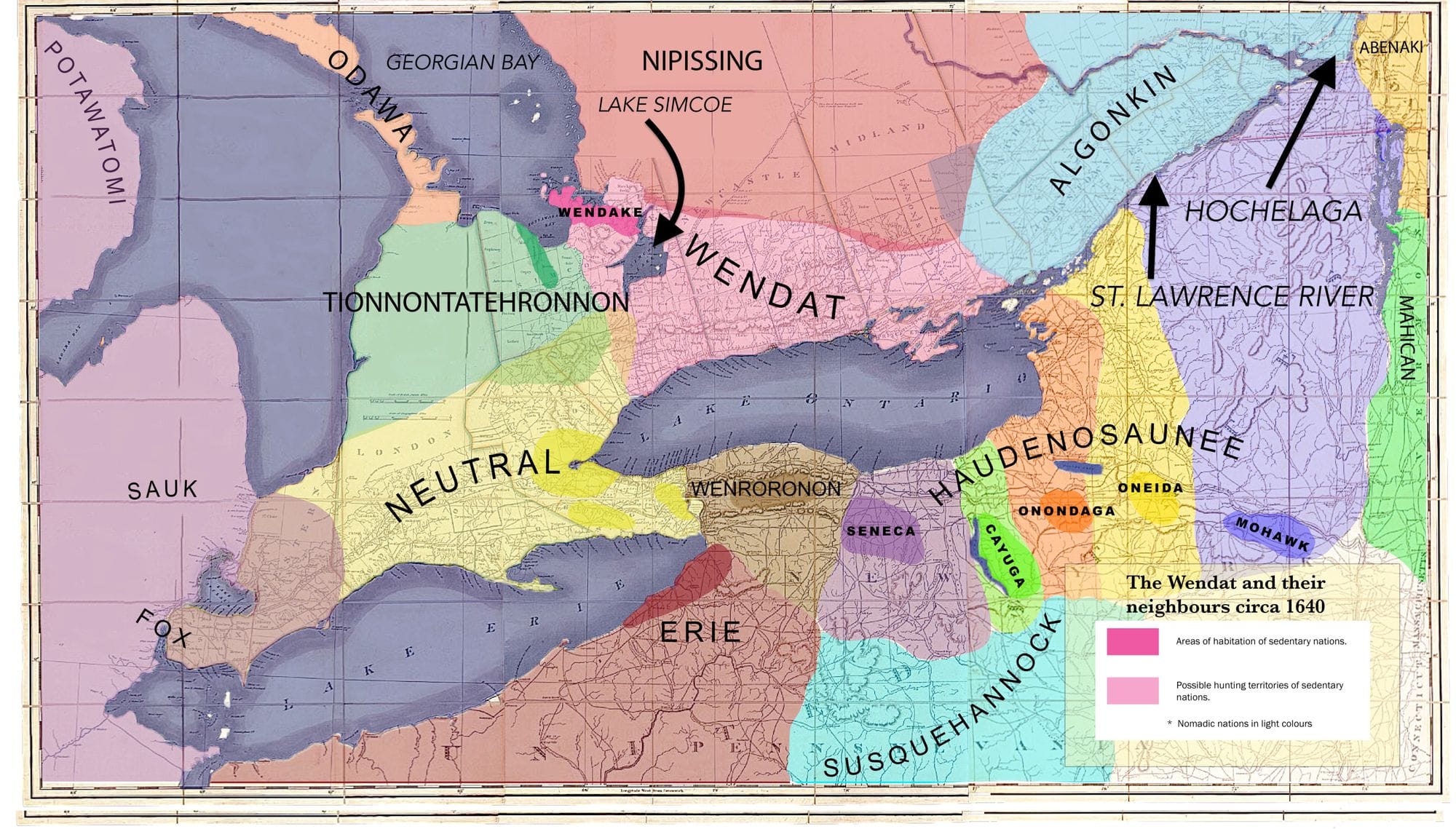

By the early 1620s, where we left things last time around, the French commercial project on the St. Lawrence River was running smoothly. Convoys of fur-laden canoes regularly made their way down the Ottawa River to the St. Lawrence each summer—amidst generally good relations between the fur trade’s two poles—the Wendat Confederacy in the west, and the French base at what is now Quebec City in the east. Together with the Innu, and the Algonquin nations along the Ottawa River, this is what I’ve been referring to as the Laurentian Coalition.

The time was approaching when New France would make the jump from commercial experiment on the margins of French society to an integrated component within a nascent global French Empire. And a key player in this transition would be Armand Jean du Plessis, known to history as Cardinal Richelieu.

Richelieu had originally begun his political career in the service of the Queen Mother, Marie de' Medici. But amid the chaotic political jostling that took place at the end of young Louis XIII’s regency, Richelieu re-invented himself as a servant to the now-adult King, and would eventually entrench himself within the monarch’s governing inner circle.

For the next two decades, French politics would be driven by a partnership between Richelieu and King Louis XIII. Indeed, it was largely through Richelieu that Louis, once in his mid-20s, started to exercise power independent from his regents. For Canada, this heralded a more stable and coherent colonial policy, as New France would no longer be whipsawed by an unstable royal court contested by multiple factions.

To (vastly) over-simplify their approach to governance, Louis and Richelieu envisioned a centralisation of the French state—a project that would require them to dismantle medieval-era traditions and laws that had allowed France’s aristocratic families to operate quasi-independent fiefdoms. It was this problem, the pair believed, that had caused the country to be divided by region and religious sect, which, in turn, had helped spark the bloody civil conflicts France had endured over the previous century (and which were discussed way back in the seventh instalment).

While their agenda included curtailing the autonomy enjoyed by Huguenot (i.e., Protestant) enclaves such as La Rochelle, Richelieu also found himself at odds with the Dévots, a hard-line Catholic faction whose members saw European affairs in good-versus-evil (which is to say, Catholic-versus-Protestant) religious terms. Though Richelieu had been consecrated a bishop, he always saw religion as coming second behind French national interests.

And so, unlike his political predecessors, Richelieu didn’t consider Canada to be just a commercial enterprise run for the benefit of a few merchants, but rather an important contributor to French geopolitical power. In a sense, Richelieu was thinking along the same lines as the Dutch, who (as we saw in our last instalment) were incorporating their Hudson River trading post into a global war effort against Spain.

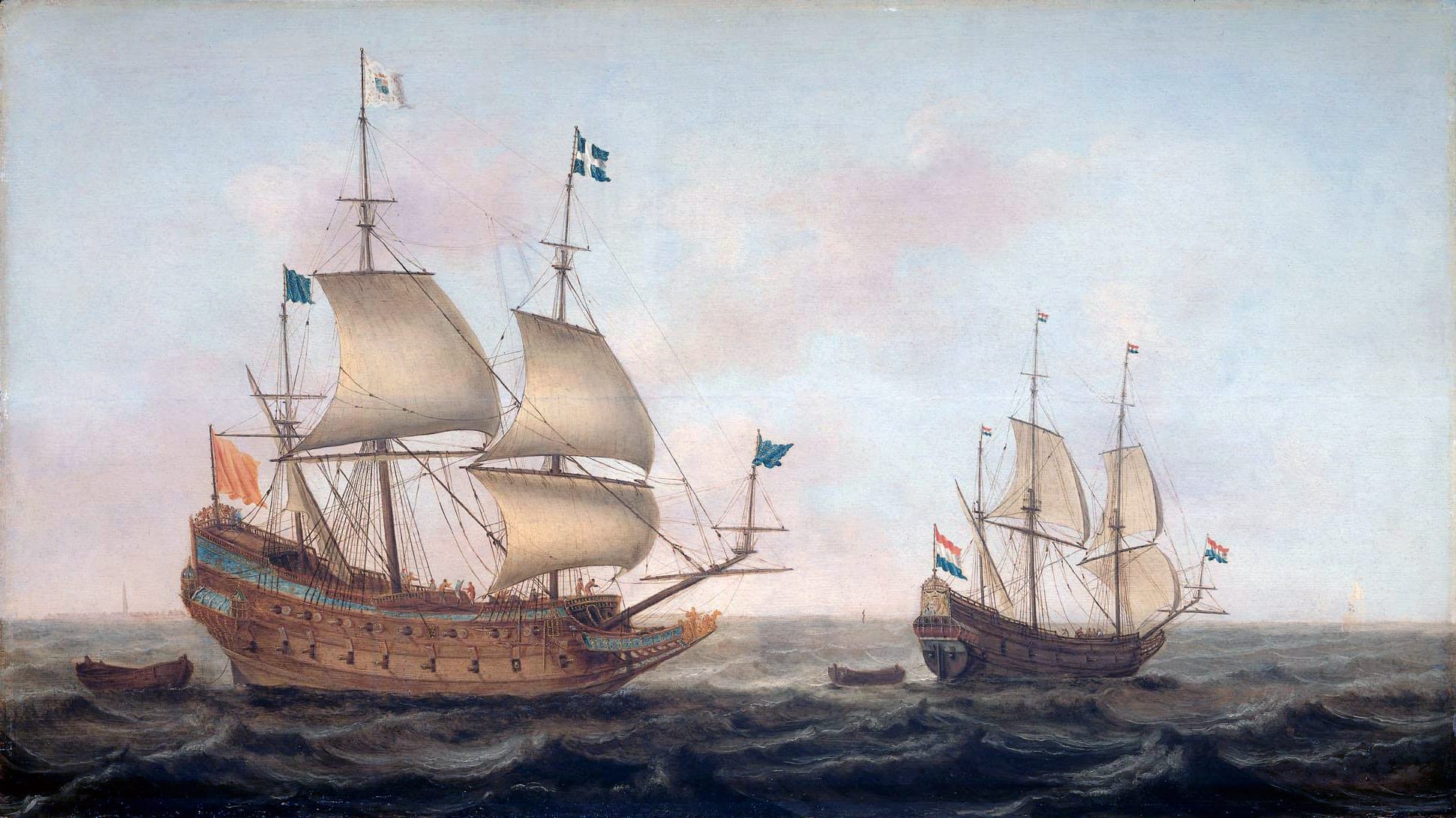

Looking around Europe, Richelieu observed that power increasingly rested on naval strength. The tenuous links that held Spain’s mighty empire together, for instance, were often being broken by English and Dutch raiders. But navies were expensive propositions for early modern states. While a mass of pikemen might be trained relatively quickly, or recruited as mercenaries, a proper navy required substantial capital investment and the work of full-time seafaring professionals. As the English and Dutch had learned, it also required forging partnerships with deep-pocketed private traders—such as those French merchants who’d been working the Canadian fur trade.

And so, for Richelieu, modernising the French navy went hand-in-hand with reforming France’s Canadian operations. And he placed both projects under the jurisdiction of the same man—Isaac de Razilly, a 38-year-old captain who had long experience in the Mediterranean.

He was also a member of the Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (also known as the Order of Saint John, the Knights Hospitalier, or simply the Hospitaliers), a Catholic military order founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem during the twelfth century. By the seventeenth century, the Hospitallers had long been pushed out of Jerusalem, and had since set up their headquarters on the island of Malta, from which they fought an endless battle against the North African raiders harassing Mediterranean shipping.

At the same time, Richelieu pushed out Quebec’s incumbent colonial viceroy—Henri de Montmorency, 4th Duke of Montmorency, whom we briefly met in our twentieth instalment. This was not so much because Montmorency had fallen afoul of Richelieu’s political or religious views, but because the Duke had treated the position more as a decorative title than a real job. (In fact, the office was just one of many that Montmorency held.) Determined to secure more energetic leadership for the colony, the Cardinal engineered Montmorency’s resignation.

The new viceroy would be Montmorency’s nephew, Henri de Lévis, Duc de Ventadour—a young aristocrat with a deep devotion to the Catholic Church. Both he and his wife were closely associated with the Jesuits, and shared Richelieu’s desire to convert Canada’s Indigenous peoples to Christianity. Indeed, the family confessor, Philibert Noyrot, taught at the Jesuit college of Bourges, and adhered to a faction within the Jesuits that wanted to take another crack at Canadian missionary work following their expulsion from Acadia in 1614 at the hands of the English (a setback that we discussed in our seventeenth instalment).

The Jesuits—a Catholic missionary institution founded in 1540—had become controversial figures in France, however. King Henri IV had banished them from the kingdom in the 1590s following their involvement with seditious Spanish-backed political schemes. Once France’s sixteenth-century Wars of Religion finally ended, Henri welcomed the Jesuits back, but many still suspected them of being beholden to Spain. When the King was assassinated by a Catholic zealot in 1610, accusations abounded that the Jesuits were involved (or at the very least, that they’d celebrated the murder).

Returning the Jesuits to New France therefore presented complications. Nevertheless, in March 1625, within just a few weeks of taking over as viceroy, Ventadour arranged for the Jesuits to assist the Franciscan Récollets, who, by now, had been performing missionary work in Quebec for several years.

In keeping with their doctrinaire Catholic approach, Ventadour and Richelieu also agreed to the creation of new restrictions on Protestants in Canada. From now on, the summer trading fleet would have to be commanded by a Catholic (a blow to the influence of Guillaume de Caën, the Huguenot trader who typically served in this role). And Protestant religious services would be barred on New France’s soil, another step in the transformation of the colony into an explicitly religious project.

In the summer of 1625, a trio of Jesuit missionaries arrived in New France, led by a former Jesuit college administrator named Charles Lallement. Joining him was Énemond Massé, who’d been part of the Jesuits’ ill-fated Acadian mission a decade earlier, and Jean de Brébeuf, a 32-year-old Norman-born missionary whose talent for languages would earn him a prominent place in Quebec’s history.

Up until this point, the Récollets had made slow progress in deciphering the Algonquin and Iroquoian tongues of their prospective Indigenous converts. Joseph Le Caron, the leader of the Récollets mission, was in the process of producing a dictionary of Wendat tongues—whose contents he’d originally compiled while living among them over the winter of 1615–16. But his work was rudimentary, and would soon be eclipsed by that of Brébeuf.

The French settlement that the Jesuits arrived at on the St. Lawrence was still tiny. Of the roughly seventy people in Quebec, only about twenty were permanent residents. Despite getting a decade-long head start, Quebec had actually been outstripped by newer European settlements in the region. About 200 Dutchmen now resided in their colony on the Hudson, and over 300 Englishmen were living in New England.

Despite getting a decade-long head start, Quebec had actually been outstripped by newer European settlements in the region. By the mid-1620s, about 200 Dutchmen were residing in their colony on the Hudson, and over 300 Englishmen were living in New England.

The arrival of the Jesuit trio was the opening move in a French campaign to close that gap. The hoped-for religious glory they’d earn, properly publicised back home, would hopefully inspire greater investment in the form of both money and manpower.

But that whole enterprise hung on the Indigenous side of the equation. Would the Christian message find a receptive audience in Canada?

In this regard, the early returns on French efforts had been decidedly mixed. By 1625, Récollet missionaries had been on the ground for more than a decade, with little to show for their work.

Le Caron seemed especially frustrated by what he saw as a total lack of any religion (as per his blinkered European conception of that category) within Indigenous society. During their training back in France, he and his fellow missionaries had learned to joust against adherents of rival faiths such as Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism. In those cases, there were rival priestly classes to use as foils, and rival theological precepts to debunk. But the Wendat didn’t provide the Récollets with any such rhetorical latch points. And Le Caron had no interest in behaving as the Spanish did—which is to say, forcing conversion rites on Indigenous populations that had no understanding of what such rituals signified.

In this regard, Le Caron was following the well-worn European tradition of associating civilisation with organised religion. From his perspective, a well-ordered society simply could not exist without a formalised set of beliefs concerning God and God’s relationship with humanity.

The French described Indigenous North Americans as les sauvages. (Indeed, Samuel de Champlain’s account of his first visit to the Americas in 1603 was titled, Des Sauvages, ou, Voyage de Samuel Champlain.) It’s tempting to translate this into English as “savages.” But that would be inaccurate. For seventeenth-century Frenchmen, sauvage was a descriptive term without an explicitly pejorative connotation. Roughly speaking, it referred to people who lived in forests, as opposed to settled European-style communities.

Of course, just because the word wasn’t an insult doesn’t mean it didn’t connote a form of moral judgment. All sorts of assumptions about the unstructured nature of life in the wilderness were bound up in the term. In the absence of a stable, sedentary lifestyle, it was believed by Europeans, there could be no law, no coherent order to society, and, most importantly for Le Caron, no true religion.

Importantly, though, sauvage indicated a cultural condition, not any kind of pre-determined racial status: A sauvage could become a Christian (just as a European Christian could become a heretic). Le Caron believed that Indigenous people were fully capable of taking up European habits, manners, and economic practices. His dream was to see them move to European-style farming villages, where they would become church-going Christians like any other.

It was in this light that Le Caron re-assessed the Récollets’ strategy following his 1615–16 trip to Wendat territory. Instead of returning to live with the Wendat (or any other Indigenous group), he focused on bringing potential Indigenous converts to live with the French at Quebec.

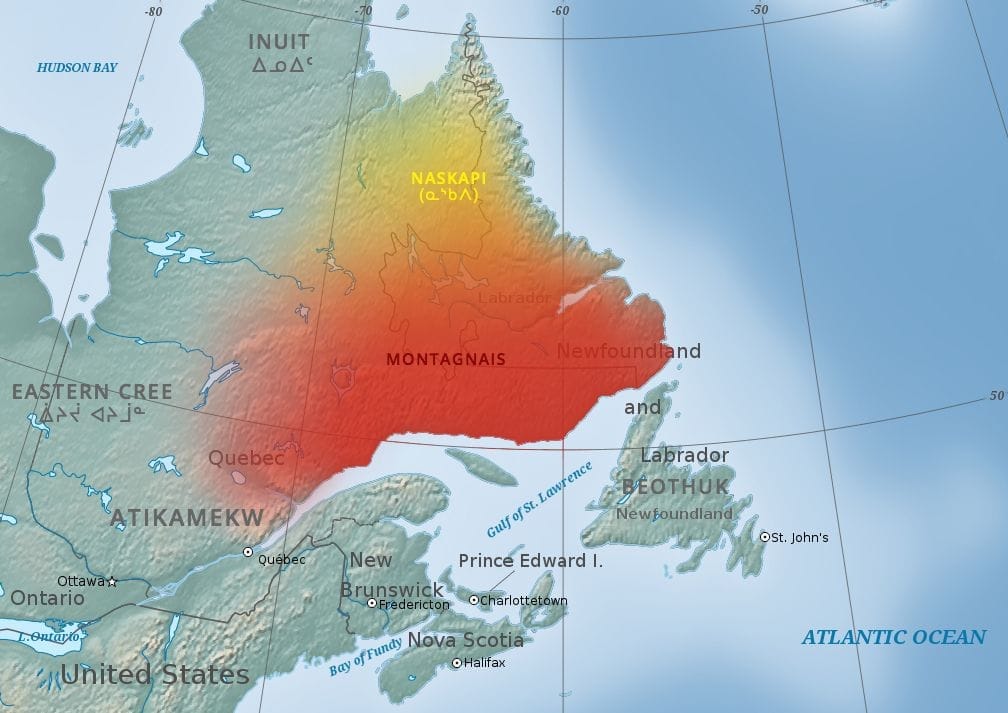

For the most part, this meant the Innu, who were based in the eastern part of what is now the province of Quebec. They were seen as less important to the fur trade (which, by now, was shifting west toward the Ottawa River), and so were becoming the Laurentian Coalition’s poor cousins.

Le Caron himself spent most of his time in France, lobbying for financial contributions to the missionary effort. But his Récollet subordinates remained in Quebec, where they started turning their modest headquarters just outside the settlement into a seminary for the education of young Indigenous boys.

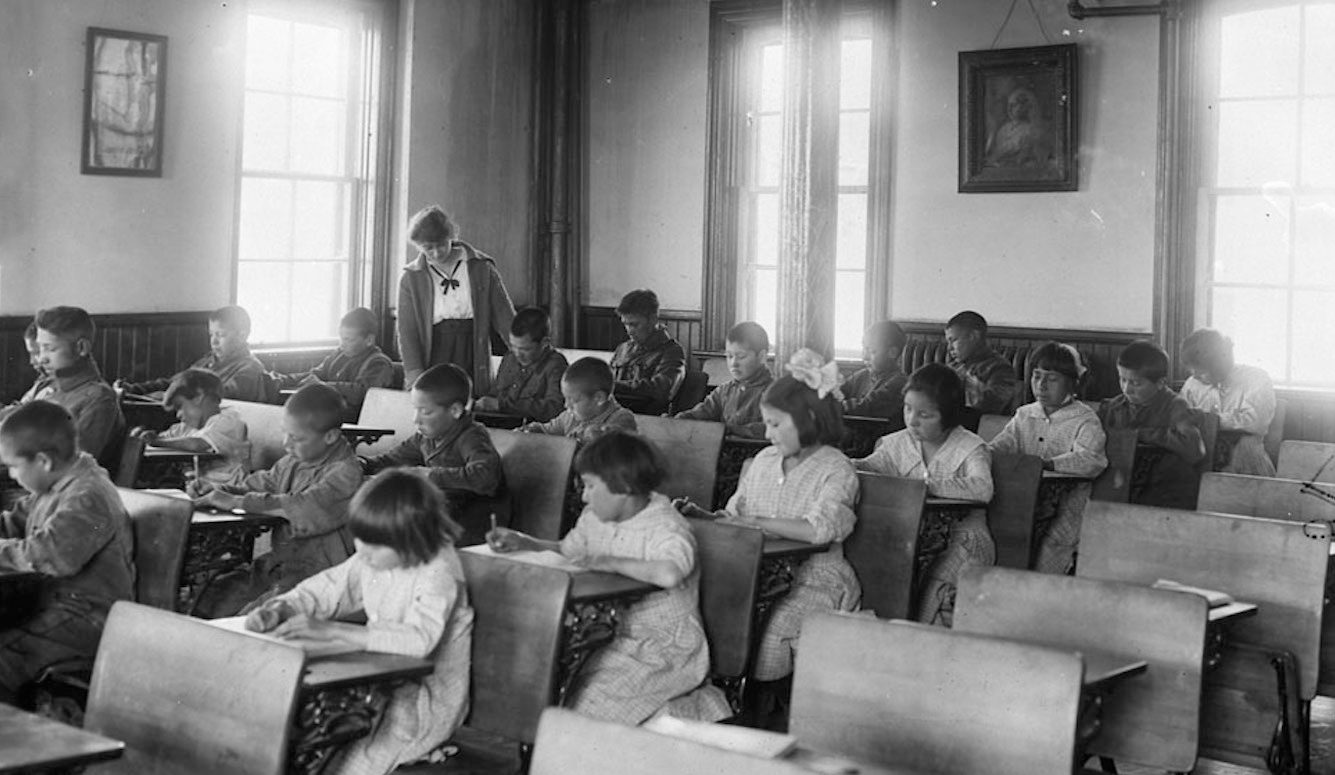

The project never really took off, however. Swapping care of one family’s children for another was a traditional way to forge bonds within the Indigenous world. But the Récollet priests were, of course, childless, and the institutional nature of their seminary didn’t exactly fit the familiar Indigenous model. Moreover, European methods of education relied heavily on stern discipline—or even physical violence—which Indigenous observers (including early Indigenous visitors to Europe) found to be abhorrent.

At any given time, the seminary hosted only one or two children. In a foreshadowing of traumas inflicted by Canada’s Residential School system in the nineteenth century, what few students there were often ran away to return home, or were pulled out by their families when news spread of the treatment they’d endured.

Even the handful of success stories turned out to be disappointments (to the missionaries, that is). In a European village, even a young and inexperienced priest would typically be treated with a degree of respect and deference by older parishioners. But Indigenous societies tend to be more gerontocratic, because children—having accumulated no experience with the hunt or other important economic activities—hold little social status. And so, while the missionaries wanted to create a Christian corps of what we would now call “influencers,” their star influencers had no real influence.

Le Caron embarked on one last missionary project in summer 1623, when he and two other Récollets—Gabriel Sagard and Nicholas Viel—joined 11 other Frenchmen in tagging along with a convoy of Wendat traders returning home after the season’s trading. Although it had been seven years since Le Caron last preached to the Wendat in their homeland, other Frenchmen had been keeping up the relationship, including translator Étienne Brûlé, who’d been living continuously with the Wendat for many years by this time.

The Wendat regarded this as something like an official diplomatic delegation, as they were aware that the missionaries were seen as powerful by other Frenchmen (even if the precise nature of that power remained unclear). But our knowledge of what happened on that trip is clouded somewhat, as the only surviving detailed account is provided by Sagard, who exhibited the usual biases in regard to Indigenous societies.

Moreover, Sagard published his report many years later, and did so with a specific political purpose. Not to get ahead of our narrative, but the Jesuits will eventually supplant the Récollets and take exclusive control over French missionary work in Canada. Sagard’s narrative describing his time among the Wendat was (in part, at least) an attempt to discredit the Jesuits, and prove that the Récollets (he, in particular) had made important progress.

With those caveats out of the way, let’s proceed to Sagard’s description of what the Récollets found in Huronia.

The French were welcomed as honoured visitors at Carhagouha, the same village that had acted as Le Caron’s base of operations in 1615. And as before, Le Caron and his colleagues refused Wendat offers to live as guests in their longhouses. Instead, they insisted on a separate space in which they could privately conduct their Christian rites; and remained aloof from the various feasts and festivals that marked the Wendat calendar.

This rejection of traditional hospitality would have struck the Wendat as odd and antisocial. It also would have been burdensome from a practical point of view, as Carhagouha was then in the process of being phased out due to the depletion of the local soils. Work had already begun on clearing land and constructing a new village nearby. The need to peel labour off from that project to build an extra cabin for the missionaries (and one that would soon be abandoned to the elements once the village moved) was presumably not appreciated.

The consensus among historians is that the Wendat treated the missionaries with more tolerance than affection. If the Wendat had their choice of French guests, they would have preferred men with guns; not only because this would at least have provided security against Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) winter raids, but also because the Wendat were becoming interested in firearms more generally.

(This is a subject we’ll be exploring more systematically in future instalments. But for now, I’ll note that the French had banned the use of muskets in the fur trade, for fear of losing their technological military advantage. In the long run, these restrictive French rules would affect the balance of power in the region, as the Dutch were far more liberal in trading guns with their own Mohawk neighbours. In part, this was a matter of leverage, as the Dutch were not always in a position to dictate the rules of trade.)

In trying to make sense of the missionaries, their Wendat hosts fell back on Indigenous understandings of the spiritual world. Within that world, there was no equivalent to the Church, or even to a distinct priestly class. Instead, the spiritual realm formed a kind of substructure to the visible world, connecting humans, animals, and the physical environment. And that network was broadly accessible to ordinary people. Everyone caught glimpses of it in dreams (which could foretell the future, or provide clues for curing illnesses). However, some particularly wise men were believed to be able to access this spiritual world more effectively than others, through ritual. In doing so, it was thought, they were sometimes able to cure their neighbours, provide a bountiful hunt, or protect warriors in battle.

But—and this is where the missionaries really knew they weren’t in Kansas anymore—these spiritual power-ups were morally neutral. They could be used to heal your friends, yes; but they could also be used to curse your enemies. (And, likewise, your enemy could use them to curse you.) It was the intent of the user that determined whether good or evil would result.

And it was through this lens that the Wendat understood the missionaries. They were clearly the wisest of the Frenchmen—men who’d discovered methods of accessing the spiritual world that even the wisest Indigenous elders hadn’t yet uncovered. This supposition (along with the demands of courtesy) is what encouraged them to listen to what the French holy men had to say.

Many missionaries understood this apparent eagerness to learn about Christianity as evidence that conversions would come easily. However, they were frequently disappointed when audiences failed to exhibit Christian behaviour in their day-to-day lives. In part, this is because the audience members weren’t coming to learn about the totalising belief system that the priests were espousing. They were more interested in practical lesson plans that would help them be more successful within their (retained) Indigenous way of life.

French missionaries were probably also confused by Indigenous rules of social etiquette, which encouraged interlocutors to be respectful and silent when someone else was holding forth—even if you disagreed with their message. For the Récollets, who’d grown up in a European world full of religious debates and rival forms of pamphleteering, this was an alien concept. As noted above, adversarial discourse had been a focus of their education. What had not been a focus was dealing with audiences whose members expressed curiosity, responded politely (or even enthusiastically), but nevertheless failed to become Christians.

For their part, the Wendat struggled to decipher the missionaries’ intentions, especially given their physical reclusiveness. The rituals they conducted in public seemed benign enough, but who knew what they got up to in their secret cabin?

Moreover, the missionaries consistently refused to direct their powers toward fairly standard objectives—like ensuring the rains came to help crops grow. The priests would have seen such a gesture as a blasphemous nod to paganism. But for the Wendat, it was baffling. If the priests refused to use Christian powers to feed and protect their friends, what was their real agenda?

There was also another factor at play. As in medieval European societies, marriages between groups were an important tool for creating alliances and demonstrating good faith. This was a lesson French fur traders had been quick to pick up on, as even temporary sexual relationships with Indigenous women were seen as a means of forging bonds within the community. But of course, Catholic missionaries were bound by a vow of chastity, so that form of bonding was off the table.

It was soon after the Récollet missionaries had established their permanent presence among the Wendat that their Jesuit reinforcements arrived at Quebec. And they were in a hurry: Brébeuf, who’d shown an early aptitude for languages while a student at the College of Rouen, was eager to visit the Wendat right away, and get started on learning their language.

As noted above, Le Caron had been having a difficult time with this project. In particular, the leader of the Récollets had found it difficult to translate core Christian concepts such as temptation, faith, and resurrection. Most sensitive of all were the ideas underlying the rites of communion. As one might expect, Le Caron struggled to explain how bread and wine turned into the body and blood of Christ using his limited Wendat vocabulary.

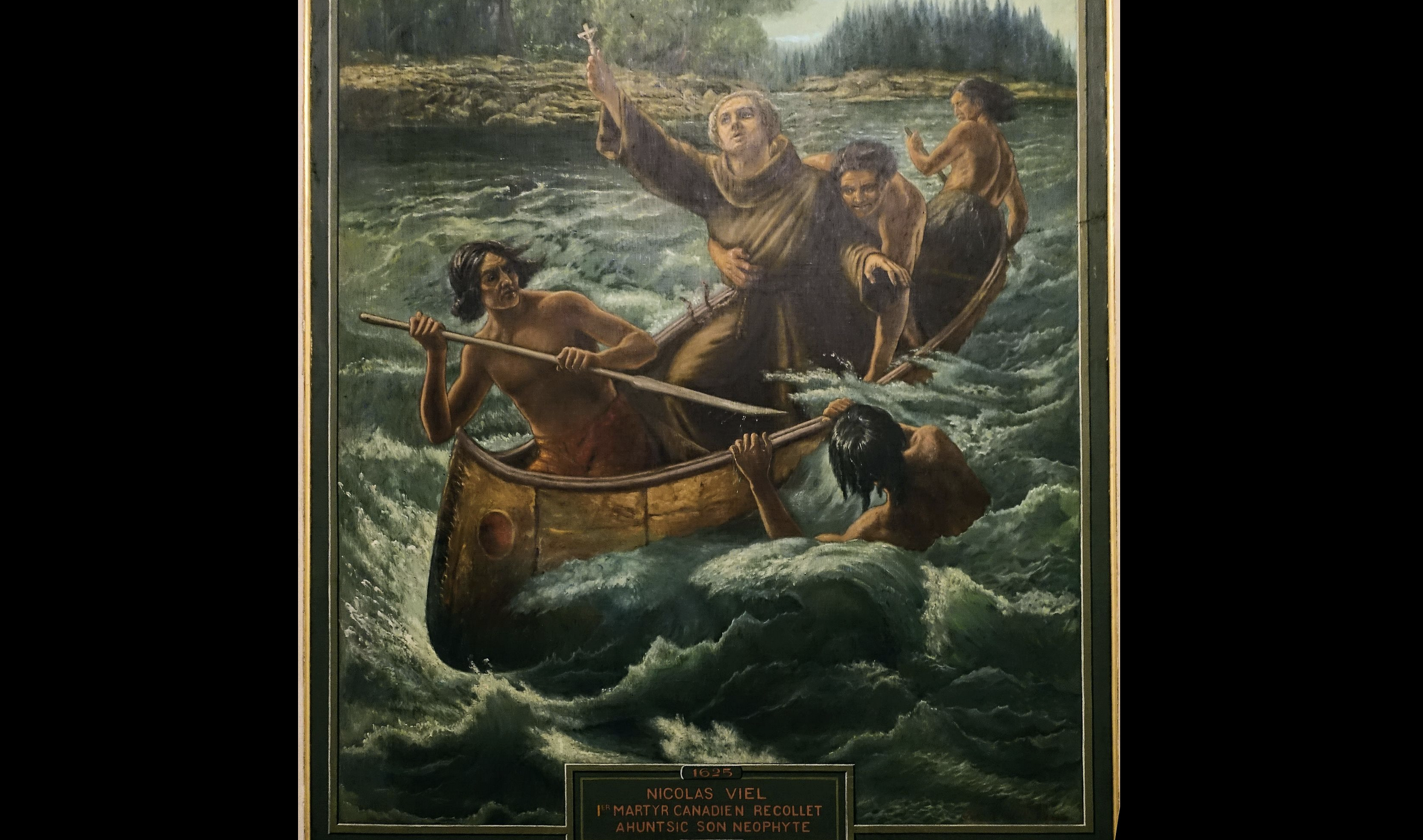

Brébeuf intended to take a more methodical approach to studying the languages of the Wendat confederacy, rather than simply jumping straight to theology. However, his hopes of immediately travelling to the Wendat in summer 1625 were dealt a tragic blow when Nicholas Viel, one of the Récollet missionaries, drowned in rough water while travelling by canoe between Quebec and Huronia. His Wendat escorts worried that they’d be held responsible for the death, and so were reluctant to complete their trading mission that summer. Brébeuf’s trip had to be delayed, at least until the French-Wendat relationship could be repaired.

Making matters worse for Brébeuf was that fact that, with both Le Caron and Sagard now back in France, Viel had been the only missionary in North America with any knowledge of the Wendat language. And so when Brébeuf did arrive in Huronia the following year, he’d be starting from scratch.

For the time being, Brébeuf would spend his time among the Innu, and soon was making greater progress with their language than any of his Récollet predecessors. Partly, this was due to his skills and training as a linguist. But the Jesuit also benefited from a much closer relationship with the translator employed by French traders in the region, a man named Nicolas Marsolet. In the past, such traders had resisted the meddling of missionaries, whom they saw as a distraction from the fur business. But Marsolet, who’d been personally recruited by Champlain back in France, was on board with the broader project of colony-building, and had ambitions of parlaying his work among the Innu into a prominent place in French colonial society.

When summer 1626 arrived, the spectre of Viel’s death still hung over the French-Wendat alliance. Nevertheless, Indigenous traders agreed to bring Brébeuf back with them to Huronia, along with a Récollet colleague named Joseph de la Roche Daillon. It was a fateful decision, as Brébeuf would end up becoming the most influential Frenchman within Wendat society, eclipsing even Brûlé, who by now had become fluent in Wendat language and customs.

This shift was seen as welcome back in Paris, where Brûlé’s loyalties had come to be seen as suspect. After so many years living apart from his fellow Frenchmen, Brûlé now often seemed to act as an advocate for the Wendat, and so couldn’t be considered an official representative of the trans-Atlantic French empire that Richelieu was trying to build. In fact, Brébeuf carried with him orders for Brûlé to return to Quebec permanently, as the plan was for the missionaries to now take over the management of the Franco-Wendat alliance.

However, both Richelieu and Brébeuf would discover that switching out personnel was not quite as easy to do in Canada as it was in Paris. Brûlé did not meekly disappear from the Canadian story, and (spoiler alert) would retain the power to upend French designs in unforeseen ways.

As for Daillon, he had another mission entirely, which was to make contact with the Neutral Confederacy that bordered the Wendat to their south on the Niagara Peninsula. The name “Neutral” comes from Champlain, who observed that this Confederacy seemed to be on good terms with both the Wendat and their Haudenosaunee rivals. (In fact, the Neutrals traded regularly with both the Wendat and the Seneca, who were the westernmost of the five Haudenosaunee nations.)

The Neutral Confederacy rivalled the Wendat in size (though precise figures are hard to know), and likely played a far more influential geopolitical role in the Great Lakes region than French observers realised.

Back in 1615, Champlain had hoped to visit the Neutral Confederacy when he’d travelled to Huronia, but was dissuaded from doing so by his hosts. The Wendat claimed that a member of the Neutral Confederacy had been killed by a Frenchman during a previous battle, and so were determined to kill the next Frenchman they laid eyes on, by way of revenge. In all likelihood, this was a fabrication, however—one intended to prevent the French from creating an alliance with another powerful confederacy; or, worse (from the Wendat perspective), using the Neutrals as middlemen in forging an alliance with the Haudenosaunee.

Why Le Caron and the Récollets chose to reopen the Neutral file is a bit of a mystery. But we do have information about what happened after Daillon set out for Neutral territory in October 1626, a few weeks after arriving in Huronia. According to French accounts, the priest met with a man called Souharissen, whom Daillon described as the great chief of the Neutrals.

Daillon also reported that the Neutrals exhibited a far more hierarchical power structure than existed in the Wendat Confederacy. The evidence for this is weak, however, and it should be remembered that French observers didn’t have a great track record of decoding Indigenous political systems.

Daillon went so far as to propose a formal trade relationship with the Neutrals, and offered to spend the winter in their territory. Souharissen, likely acting in consultation with other Neutral chiefs, hesitated, knowing that hosting a Frenchman would upset the Wendat. And so he stalled for time, and dispatched messengers to the Wendat Confederacy in a bid to clarify the situation.

Although the Neutrals were likely tempted by the prospect of a closer relationship with the French, their priority was maintaining a positive relationship with neighbouring Indigenous confederacies. Moreover, the Neutrals were already able to acquire European trade goods—French commodities from the Wendat, and Dutch commodities from the Haudenosaunee. And so there was little to gain from a direct relationship with the French, and much to lose.

Ultimately, the Neutrals managed to extricate themselves from the awkward diplomatic situation. They explained to Daillon that although they welcomed French friendship, they didn’t feel they could competently access the St. Lawrence directly from their territory on the western shores of Lake Ontario. And so they thought it best to continue trading with the French by using Wendat intermediaries. This was almost certainly a pretext, but it allowed Souharissen to get out of the predicament without offending either the Wendat, the French, or the Haudenosaunee.

Daillon’s failure with the Neutrals would prove costly for the Récollets, whose reputation among the Wendat had now been severely undermined. Daillon returned to Quebec in disgrace, and would prove to be the last Récollet missionary to set foot in Huronia. From now on, the French mission to the Wendat mission would be an exclusively Jesuit affair.