sex differences

Tickle vs. Giggle

Women-only spaces are valuable, and we should prevent biological males from accessing them, whatever their stated gender identity.

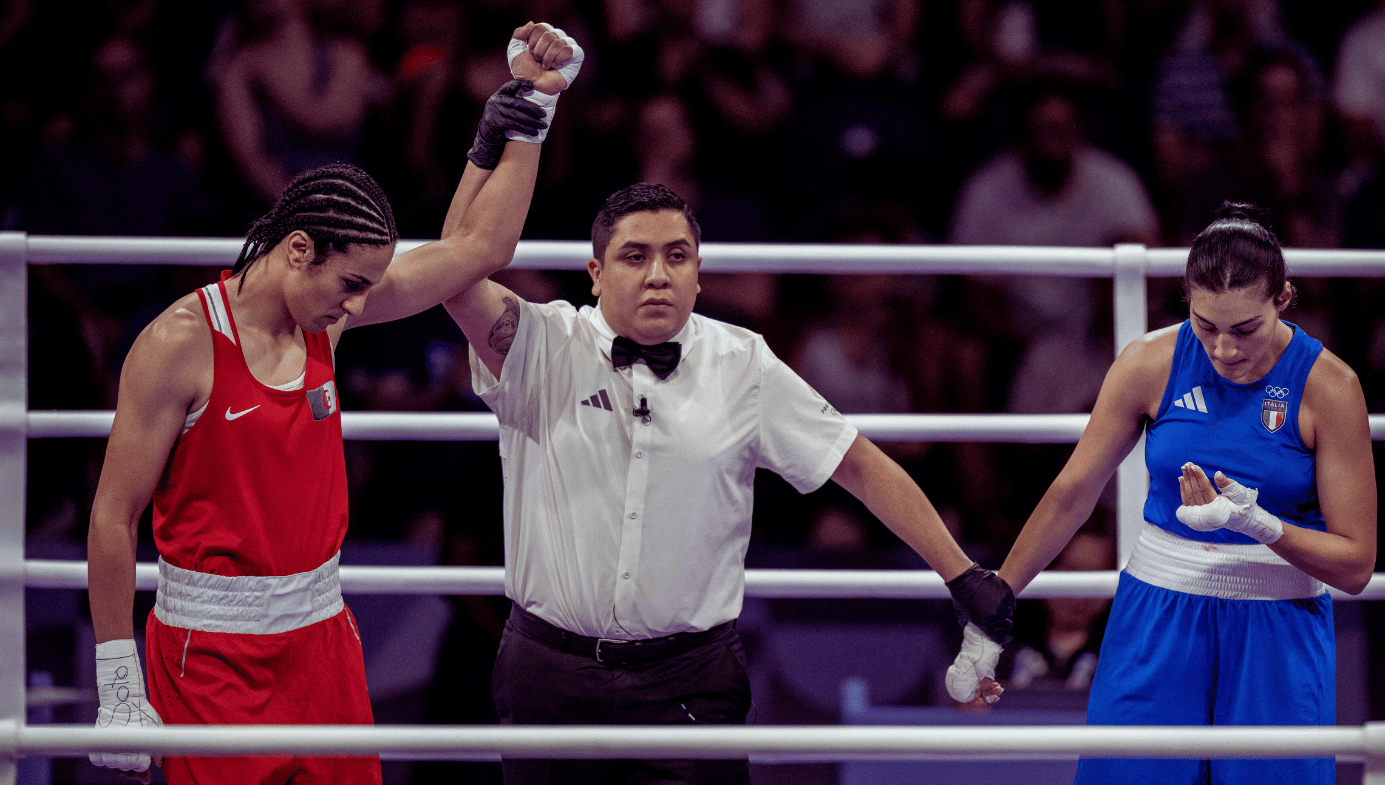

In his Reasons for Judgement delivered this Friday 23 August in the legal case of Tickle v. Giggle, Justice Robert Bromwich declared that “Roxanne Tickle was of the male sex at the time of birth, but is now recognised by an official updated Queensland birth certificate… as being of the female sex.” Tickle was male, then, but is now recognised as female. Just in case you’re envisaging a reverse version of the intersex condition 5-ARD that we heard so much about during the Olympics, no, this is not that (no such reverse condition exists). This is about a straightforward male supposedly becoming an admittedly not-so-straightforward female.

The case concerned Tickle’s access to a female-only social media platform (‘Giggle’), specifically, whether his exclusion from the platform was a form of discrimination. There were big social issues at stake. Biological sex has historically been an axis of oppression and remains one in many countries. It had become unclear whether the law in Australia could recognise biological sex, or only the adjacent concept of legal sex. Since 2018, when the UK considered introducing self-identification for “gender recognition,” there has been a huge public debate over what a woman is. Gender-critical feminists and their allies say that a woman is an adult human female (‘female’ here refers to biological sex, not legal sex); trans activists and their allies say that anyone who identifies as a woman is a woman, ergo, transwomen are women. Most gender-critical feminists think woman is a ‘natural’ kind, something you are from birth and will remain throughout your life; most trans activists think woman is a ‘social’ kind, something that can change over the course of your life, that you can cease to be or start to be. This has led to especially fierce debate over female-only spaces, and the question of whether spaces that previously excluded males on the basis of their biological sex must now admit them on the basis of their self-identified or legal sex.

I have never read a judgement as obtuse as Bromwich’s. He simply declares all these fraught social issues to be irrelevant. Of biological sex he says, “it is not my role in forming a judgement about the issues in dispute, and the relevant law, to have regard to the evolutionary or biological definitions or features of human sex.” It is as though biological sex were just an esoteric scientific matter that only a few experts could possibly know or care about, and legal sex is the thing most people mean when they talk about sex (“sex is not confined to being a biological concept… but rather takes a broader ordinary meaning”; “in its contemporary ordinary meaning, sex is changeable”). He never grants, not once in ninety-three pages, that biological sex is an important ordinary concept, even if it’s not the concept that the law tracks.

About what a woman is, he says “Any debate around the concept of woman, of womanhood, or gender more broadly as a natural, biological, or social construct falls well outside what I must, legally, determine in this case.” This is an extraordinary assertion, given that his judgement determines that men with ‘woman’ gender identities cannot be excluded from women-only spaces.

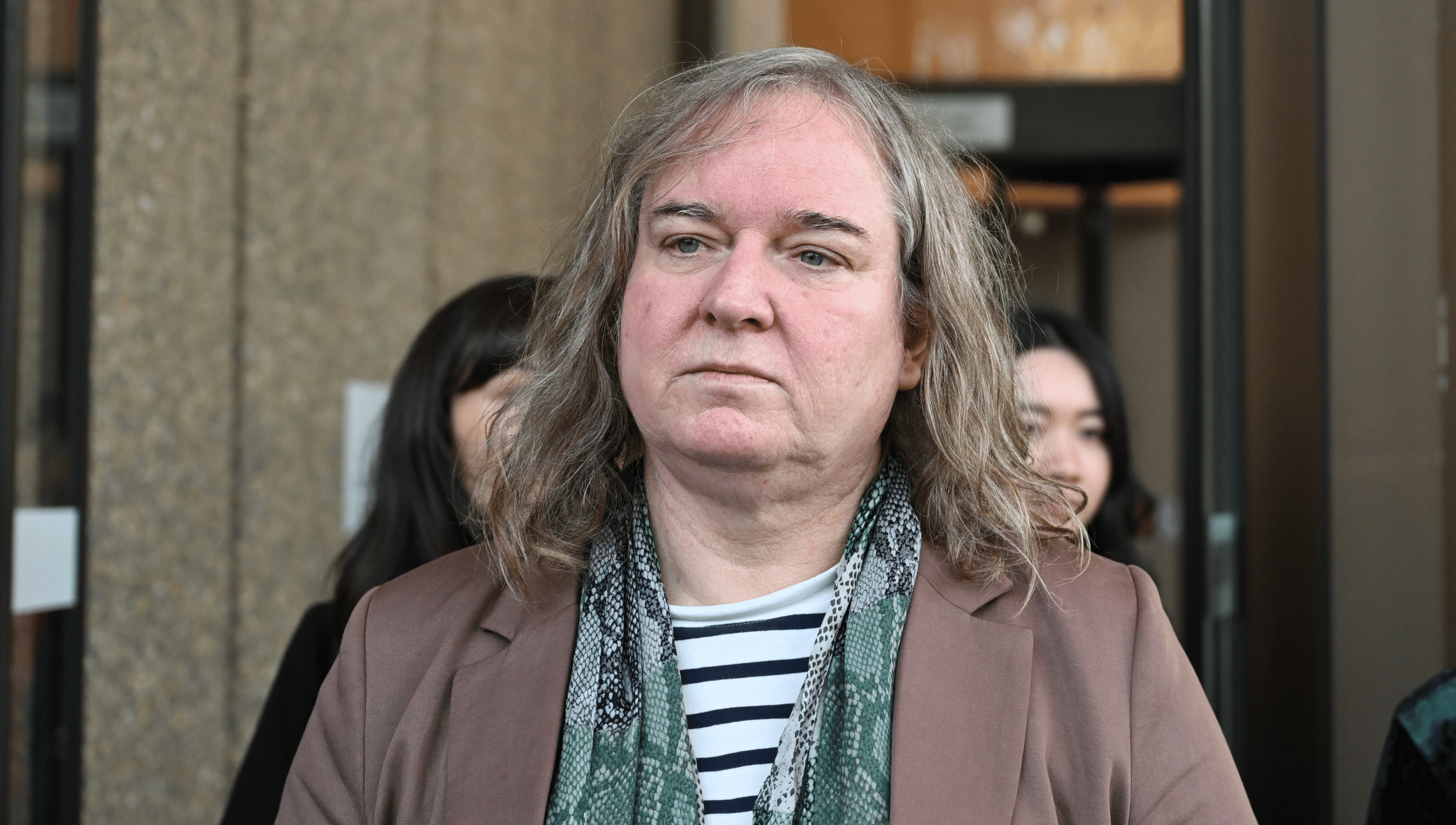

Helen Joyce’s expert evidence as to the importance of women-only spaces comes in for the most contemptuous treatment from Bromwich. He notes her view of “the importance of single-sex spaces such as bathrooms for the protection of women and girls from sexual assault and harassment, as well as for women’s privacy and dignity, mutual organisation, aid and comfort.” But he waves it away: “She is entitled to her opinion,” he writes, “but it is of no assistance to the respondents’ case, or to this Court.” Bromwich declares Joyce to have “lacked sufficient expertise for the exception to the opinion rule to apply,” since she is a “journalist and author” who “has a PhD in mathematics, but does not have any formal education or qualifications even in biology, let alone in gender, sex or law.” He does not even appear to accept that her registered human rights charity is such, instead describing it as “an organisation… which she describes as a human rights organisation.” He dismisses her with the comment, “For the purposes of this proceeding, she is not an expert at all. She has no recognised expertise in any of the areas in which she expresses an opinion.” This is a remarkable claim to make about an accomplished journalist who has published a book on the ideology of trans activism and its social implications, and who is a director of the UK’s sex-based human rights charity Sex Matters. Bromwich’s real objection to Joyce may well be ideological, since, as he notes, Joyce “is strongly … committed to the idea that transgender women do not exist.” Obviously, this very much conflicts with his own view that Roxanne Tickle is a female.

I asked Joyce what her reaction was to this disparagement of her in the judgement. She replied,

What help would it be for me to be an academic in gender or sex to give the evidence Sex Matters has gathered on the need for genuinely single-sex spaces? We have actually done that research, and as far as I know no organisation anywhere else has. … I’m absolutely certain that if someone who worked for a UK human rights charity that pushed transgender ideology [had been put forward], that person would have been accepted as an expert. … This is a really obviously biased decision.

In his verdict, Bromwich found Giggle’s exclusion of Tickle to be indirect discrimination on the basis of gender identity. He did not find direct discrimination because he accepted that the app’s CEO, Sall Grover, was not likely to have known what Tickle’s gender identity was simply from looking at a photograph of him. Such a method could not reliably “distinguish between cisgender men and transgender women” (i.e., Grover may reasonably have assumed Tickle to be a man). Indirect discrimination “is the imposition, or proposed imposition, of a condition, requirement or practice that has, or is likely to have, the effect of disadvantaging a person relative to another person or persons who have a different gender identity.” To understand this, we need to get a grip on Bromwich’s interpretation of the same versus a different gender identity. And to understand that, we need to know what he thinks gender identity is. This is where things get a bit strange, because while gender identity is defined in the Sex Discrimination Act, Justice Bromwich appears to have something different in mind in his judgement.

The Sex Discrimination Act defines gender identity as “the gender-related identity, appearance or mannerisms or other gender-related characteristics of a person (whether by way of medical intervention or not), with or without regard to the person’s designated sex at birth.” It does not define ‘gender’—or specify which features of identity, which characteristics of a person, and which mannerisms or aspects of appearance are relevant. But Justice Bromwich writes that, “The applicant alleges being removed from the App upon the basis of her gender identity as a transgender woman.” He also talks about the “imposed condition” of the Giggle app being “that a person must be a cisgender woman or be determined as having cisgendered female physical characteristics by Ms Grover on review of their photograph,” and finds that to be a case of indirect discrimination on the basis of gender identity.

So it would appear that he thinks transgender woman and cisgender woman are gender identities. He writes of “persons who have the same characteristics as the aggrieved person, here having the same gender identity as Ms Tickle, namely that of a transgender woman.” To figure out whether someone has been disadvantaged we must first establish the relevant comparison class. Who does Tickle have “the same” gender identity as—if anyone—and who does Tickle have a ‘different’ gender identity from? Are transgender woman and cisgender woman the same, or different? Bromwich writes:

As to exclusion, ordinarily there is a need for a careful comparator exercise to be carried out, in order to identify how and why a condition, requirement or practice imposed or proposed to be imposed has or is likely to have the effect of disadvantaging the person indirectly discriminated against, or persons who have the same characteristics of the aggrieved person, here having the same gender identity as Ms Tickle, namely that of a transgender woman. This requirement must still be addressed, but on the way in which the evidence has unfolded and the competing arguments advanced, it is straightforward.

Why does he think it’s straightforward? Because “the existence of the condition and its effect is not disputed or otherwise in issue.” Bromwich seems to be simply assuming that the comparison class is cisgender women, so that a face-screening method that looks for signs of maleness will disadvantage transgender women. The app is ostensibly for women, but the imposed condition disadvantages those ‘women’ who have an additional protected attribute, namely gender identity. This raises some interesting questions. Suppose that butch lesbian women, trans men, and other gender non-conforming females were excluded from the app. Would they have an indirect discrimination claim on a par with Tickle’s? Is this verdict really about the difficulty of using sex-detection methods in a context where there is deliberate confounding of sex-based appearance going on? Or—despite Bromwich’s explicit denial that he is weighing in on the matter of who is a woman—is it actually an assertion of the activist slogan that trans women are women?

If the comparison class were cisgender men, then Tickle would not have been treated differently from them, or disadvantaged, since all cisgender men are excluded from the app. Discrimination is easier to establish in cases where there are only two groups: in the old days, there were just biological females and biological males, and to decide whether sex-based discrimination against a female had occurred, you only had to compare her treatment with that of males. With gender identity, things are a lot less clear, because there may be more than two gender identities, and it is unclear which group we should be using as our comparison. Bromwich has assumed the relevant group is cisgender women, but has provided no reasons to establish that, or to explain why it isn’t cisgender men.

The Sex Discrimination Act includes a “reasonableness test,” such that the imposed condition (in Giggle’s case, the sex screening) wouldn’t count as discrimination so long as it was reasonable. To determine reasonableness requires considering “the nature and extent of the disadvantage,” “the feasibility of overcoming or mitigating the disadvantage,” and “whether the disadvantage is proportionate to the result sought by the person who imposes… the condition.” Strangely, the respondents did not rely on this provision, a version of which gets a lot of airtime in the UK’s parallel debate.

Women-only spaces are important to women, and more than proportionate to the disadvantage experienced by the few excluded males who would have liked to be included in these spaces. As things stand, at least until the verdict is appealed in the High Court, those who use women-only spaces appear to have little choice but to either tolerate the self-inclusion of these new legal females, or to self-exclude until sex-based exemptions are reinstated.