Podcast

Podcast #239: Justin Trudeau’s Ominous Online Harms Act: ‘Minority Report’ Comes to Canada

Jonathan Kay talks to Atlantic Magazine staff writer Conor Friedersdorf about a censorious government bill that would allow officials to investigate Canadians for things they haven’t done yet.

Jonathan Kay: Welcome to the Quillette podcast. I’m Jonathan Kay. And as your podcast software may already have indicated to you, this is a short episode. I’ve even cast aside the usual boilerplate intro so I can dive in real quick.

Don’t worry, my co-host Iona and I will still be serving up long-form podcasts on a regular basis, but we’ll also be mixing in some shorter, newsier episodes when circumstances warrant.

Case in point: the conversation you’ll soon be hearing between me and Atlantic magazine writer Conor Friedersdorf. It’s an interview I arranged after reading Conor’s eye-opening 6 June Atlantic article entitled Canada’s Extremist Attack on Free Speech, in which Conor analyses an ominous new Canadian bill making its way through Parliament.

That bill, known as the Online Harms Act, would allow the government to throw people in jail, potentially for the rest of their lives, if found guilty of promoting genocidal hate speech. The Online Harms Act would also allow the government to throw citizens in jail—again, potentially for the rest of their lives—if a court finds that they were motivated by hatred in contravening any act of Parliament.

Worst of all, from a civil-liberties point of view, Justin Trudeau’s Online Harms Act would allow government officials to haul citizens before tribunals on suspicion that they might say something hateful in the future. If that sounds like science fiction, yes, you’ve probably seen at least one movie with that plot line.

Needless to say, this legislation has attracted lots of criticism in Canada, including from none other than famed novelist Margaret Atwood. But I was surprised to see that its provisions are so draconian and so alarming to defenders of free speech that the bill is even getting attention in the United States.

If this account of the bill is true, it’s Lettres de Cachet all over again. The possibilities for revenge false accusations + thoughtcrime stuff are sooo inviting! Trudeau’s Orwellian online harms bill https://t.co/GziivgfNGt

— Margaret E Atwood (@MargaretAtwood) March 9, 2024

Indeed, in Conor’s 6 June article, he wrote this of Justin Trudeau, Justice Minister Arif Durrani, and their Liberal colleagues:

No one who favors allowing the state to imprison people for mere speech, or severely constraining a person’s liberty in anticipation of alleged hate speech they have yet to utter, is fit for leadership in a liberal democracy. Every elected official who has supported the unamended bill should be ousted at the next opportunity by voters who grasp the fraught, authoritarian folly of this extremist proposal.

For more on Justin Trudeau’s Online Harms Act, here is the author of those words, Atlantic magazine staff writer Conor Friedersdorf.

J.K.: Conor, how did you even find out about this story?

C.F.: I saw that the Attorney General of Canada tweeted something about needing the ability to stop hate crimes before they happen, or something with that phrasing. And I thought to myself: What do you mean “stop crime before it happens”? Is this some kind of science fiction law that you’re referring to that you’re going to pass?

So, I just Googled around for a minute, and I saw that the Online Harms Act has been debated for a long time. I had heard about it in the context of mandates on [online media] platforms about what their responsibilities are for what people post and don’t post. But I hadn’t originally realised [the full extent of the law’s provisions] when, I think, Elon Musk might have been tweeting about it.

This is insane https://t.co/6ZLWHgdJKX

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) March 12, 2024

I hadn’t realised that there was this other aspect to it. And as soon as I started Googling and Twitter-searching a bit, I saw that I think FIRE had put out a statement, and a couple other free-speech people who I generally trust on those issues had raised alarms, and so I started doing some reading. And at first, the tenor of the objections were so extreme that I thought: I wonder if I’m going to find that when I read the text of the legislation myself, I’m going to be a bit less alarmed?

J.K.: Which often happens, right?

C.F.: Yeah, it does. But in this case, I found [it wasn’t the case]. I was astonished by what I was reading. In fact, before I even got to the part about preventing a crime before it happens, the parts of the bill that ostensibly were going to try and do that, I saw the line [indicating that if] you advocate for genocide, you’re liable for a life sentence in prison.

And I thought, wow, a life sentence in prison for mere speech. I assume that people regularly get less than that after murders or rapes in Canada. It was just astonishing to me. Wait a minute, this is madness.

J.K.: Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government did something clever here. They lumped in laws against child porn, stuff that everybody hates and wants banned. It makes it difficult for conservatives to object to it. On the other hand, other parts of the law are clearly animated by what might broadly be called “anti-racism” type speech prohibition.

So from an anti-speech point of view, it’s kind of like something for everyone. Is there any possibility this kind of law would be constitutional in the United States?

C.F.: No. It certainly would trample on the First Amendment. You can tell me whether this would pass muster under Canada’s constitutional protections, which I am much less familiar with than those in the United States. I’ve seen some indications that there would at least be disputes raised and adjudicated, but I don’t know how they would be resolved.

J.K.: Even in Canada, which has lower free-speech protections than in the United States, it’s very difficult to see how this would pass constitutional muster, especially the future-crime, or as you more correctly call it, being more of a Philip K. Dick expert, “PreCrime.”

And of course, unfortunately, this summons to mind Tom Cruise [in Minority Report], about whom everybody has their own views. But it isn’t quite that they [the Canadian government] throw you in the slammer if they’re worried that, like, you’re going to misgender somebody or talk about how much you hate Uzbeks or whatever. Could you talk about what happens if you’re suspected of future crime?

C.F.: Yes. I don’t have this in front of me right now. But, as I recall, it requires a sign-off from a government official [the Attorney-General]. And it allows a hearing. And then at that point, the process seems to look a lot like the kind of process that you would go through for a restraining order. But instead of saying that you can’t go within x number of feet of someone, because you’ve been doing similar behaviour in the past or something, instead it’s about whether there’s a likelihood that you’re going to commit a hate crime in the future.

You could imagine a little bit of overlap between the category of things that you could call hate crime and the category of things that you could call harassment. So you could plausibly get a restraining order in the United States, or I imagine in Canada, if someone kept coming to your house late at night and knocking on the door and yelling racial slurs at you, right? You could get a restraining order for that. If that were all we were talking about, it’d probably be uncontroversial and pass legal muster, but the way that hate crime is defined under the Online Harms Act, it can be mere speech.

It can even be mere speech that isn’t even uttered in person, and so could be construed by some stretch as fighting words. It can be mere speech that is only online. This provision would seem to apply to someone who I had a reasonable suspicion would denigrate me at some point in the future on Twitter. Now, I can think of a number of people who I have a strong suspicion will denigrate me at some point in the future on Twitter…

J.K.: On the basis of this interview, in fact.

C.F.: Maybe! You know, they’ve denigrated me on Twitter in the past. I’m likely to write things on the same topic that cause them to be so upset in the future. It just seems preposterous to me that I could bring them before a judge.

J.K.: Although, in fairness, they’d have to denigrate you on the basis of race, religion, gender, or analogous grounds. It couldn’t just be, “Oh, there’s another crap column from Conor, or another crap interview from Jon Kay.” It would have to be, “there’s another crap interview from Jon Kay, that notorious Jew,” or something like that.

C.F.: Oh, I mean, it could be “this privileged cis white man,” right?

J.K.: As you make clear in the article, [this bill] is at an early [legislative] stage. I won’t bog people down with the legislative protocols in Canada, but there’s a first reading, there’s a second reading, there’s a third reading. We have what passes for a senate here that gets involved, and then the governor general signs off.

But could I ask you about the reaction to your column? Like, did people say, “Oh, Connor, you must be mistaken. This must be Belarus or something like that. Canada is a liberal democracy.” Like, were people weirded out by what you were reporting?

C.F.: Yes. You know, the piece actually did relatively well.

J.K.: Canadian clicks. Canadians love when Americans write about them, even when it’s a shanda like this.

C.F.: You were saying earlier that in fairness, it would have to be denigration on the basis of protected characteristics [to be covered by the law]. And there is this other caveat that I mentioned in passing in the article—that there’s a bit of a check on this, in that before it gets to the judge, there has to be another government official [the Attorney General] that signs off on this sort of proceeding. That’s good, insofar as it would presumably [prevent] rampant use.

On the other hand, when I think of the kinds of people who need protection, something like a restraining order, it generally isn’t the most high-profile cases you can think of—[victims] who have access to a government minister who’s going to sign off. [Instead], it’s the relatively powerless people that you would worry about the most. And the idea of a kind of partisan party official signing off on which [cases] to allow to go to the pre-crime [adjudication] phase, to me, is alarming in its own right.

Especially in the context of, you know, we’re talking about: What is hate speech? What is genocide, for that matter? It could hardly be more contested than it is right now. We literally have two rival camps in the Israel-Palestine conflict who are insisting that the other camp is guilty of genocide, or supporting genocide.

We have these phrases like “globalise the intifada,” and “from the river to the sea,” that some people believe to be genocidal phrases… and other people say no. And you have IDF officials or far-right political figures in Israel saying things that seem a lot like they want to kill all the Palestinians. Those are kind of the most extreme of the Israeli statements—but let’s say they get retweeted by someone in Canada. Is that sufficient to get penalised under this law? It seems like it’s taking one of the most contested subjects in the world at the moment, and raising the prospect that you’ll go to prison possibly for life for saying it.

In terms of the reactions, I didn’t get a ton of push-back. I didn’t get a ton of people saying, no, this law is good. What I got were some people who thought that my piece was too alarmist. You know, they said, “look, this still has to go through a second reading. This government could fall before it even passes. And then at that point, it’s going to go through court review.”

All that’s correct, but you know, I tried to focus [on this theme] at the end: even if [this bill] doesn’t become law, if you champion this piece of legislation, I don’t know that you can be trusted with power in a liberal democracy.

It just seems to cross such extreme lines to me. Pre-crime is not a line we want to cross, nor is life imprisonment for mere speech, and I could have written a much longer piece that delved into the many significant different pieces of this legislation. Because I have other objections to some of the other parts of it.

But those are complex areas of law. Like, what are the platforms going to be compelled to do with some kinds of content? They’re complicated, evolving questions. And I think reasonable people disagree about them. And I might have a particular point of view about how these things ought to be adjudicated, but I’m not going to say that anyone who disagrees with me isn’t fit for government.

On the other hand, the pre-crime stuff and the life imprisonment for mere speech, these seem to me just so extreme. And I don’t understand why, in this moment when there’s so much alarm about fascism, about how we need to protect democracy, these seem like the kinds of tools that would terrify people if Donald Trump were to say that he was going to start wielding them.

These seem like the kinds of [government censorship] tools that would terrify people if Donald Trump were to say that he was going to start wielding them.

It’s certainly not unimaginable that if this law were to pass sometime in the near future, there would be a right-leaning government in Canada that used it in ways that the left hated. So, it’s baffling to me that, on a high-profile piece of legislation that at least one high-profile member of Justin Trudeau’s government is [pushing] on Twitter to this day, that these extreme things would be a part of it.

We need to define hatred in the Criminal Code. We need strict penalties for violent acts of hate. We need the ability to stop an anticipated hate crime from occurring.

— Arif Virani (@viraniarif) May 31, 2024

The Online Harms Act does all of this. The Conservatives need to get on board. Now. #StopHate #ProtectKids

J.K.: And I’m glad you raised the issue of how a conservative government might treat this kind of legislative tool. And the example you gave—“from the river to the sea,” which means either “exterminate all the Jews in Israel” or it means “let’s create a pluralistic thriving multicultural democracy between the river and the sea where everyone gets along.” You get two different views on that. And do Liberals really want a conservative government in power a year or two from now throwing protesters in jail on the basis of that chant?

One final question… When Justin Trudeau’s government came into power about a decade ago, there were many classical liberals and progressives in the United States who saw him as a kind of inspirational figure to some extent.

He was internationalist, he was kind of like the anti-Trump, he was all about free trade, he was young. I know you don’t follow Canadian affairs as your usual beat, but to the extent you follow it, are you surprised that Trudeau’s government is giving us this kind of thing?

C.F.: There was one other story that surprised me about the Trudeau government. It involved freezing the bank assets of the [protesting] truckers who were driving in and blocking streets [in Ottawa]. It struck me as very troubling, from a due-process perspective, at the time. So I guess I was a bit less surprised this time around that something would shock me in the kind of civil-liberties way from the Trudeau government, but I was still shocked by the extent of this.

I will say that, you know, having seen Scotland, the cradle of the Enlightenment, do this on speech and just observing the drift of progressive spaces over time, it is in keeping with this notion—that is very strange to me—that mere speech is so harmful that we need to bring about these draconian legal processes to punish it.

And a question that I’ve been asking people in the last few days on Twitter: look, generally, if you are going to impose life in prison as a possible sentence for something, [typically] you can cite a bunch of examples of that crime happening in the past where you think the sentence that was deserved was life in prison… and I’ve yet to find anyone who can point to some instance in Canada’s past and say, this person verbally supported calling for genocide and the penalty should have been life in prison.

As far as I know, it’s not something that is a live problem—people in Canada calling left and right for genocide. If anything like this law ever passed, I suspect that it would be immigrants of one kind or another who would be most likely to run afoul of it, because they [are the ones who] tend to have the least sophisticated read on the country that they are moving to and what exactly you can get away with and what you can’t get away with.

It’s much easier to get a read on that if you’re someone who grew up in the country and attended its universities and know not only the formal rules and the informal rules, but also the pulse at the moment. And so it tends to be people who are relatively new to the society or people who are relatively marginalised within the society who tend to be punished more often by overreaching speech codes.

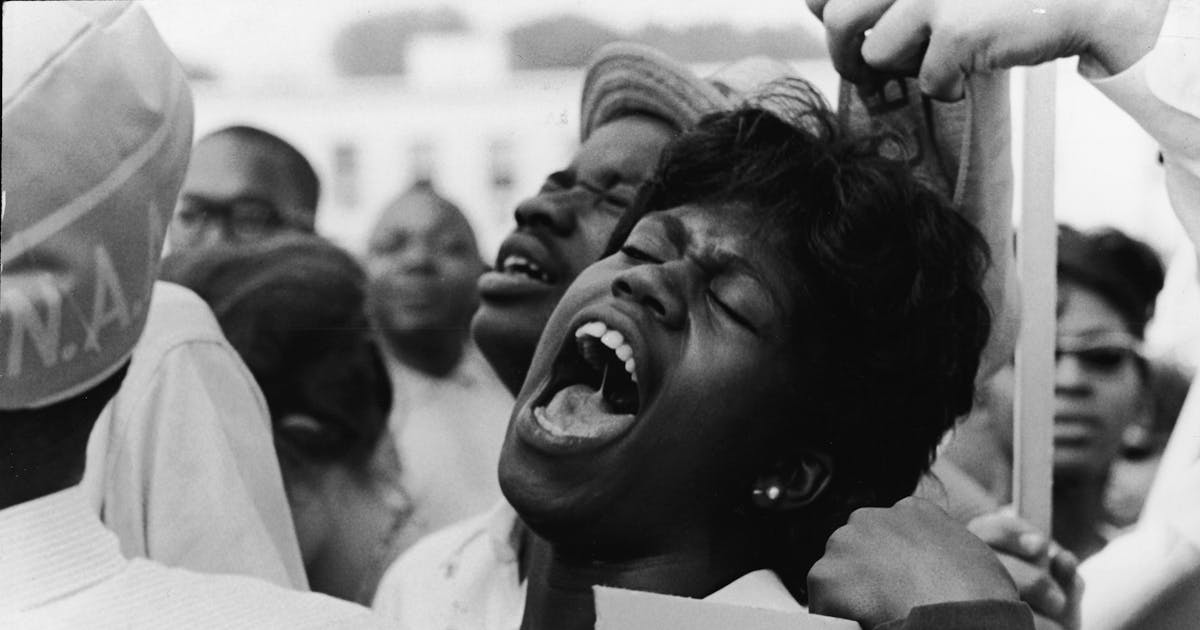

Henry Louis Gates is the first person I saw to put it well, in response to the earliest speech codes of the 1990s on college campuses and the rise of the critical race theory movement. Very early on, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. reviewed a book called Words That Wound, in The New Republic.

And he had a long review about how important free speech had always been to the civil rights movement and to other movements on behalf of disfavoured groups in society. And he grappled with why the critical race theorists were moving away from associating free speech with a tool for the powerless. He wrote [about why this was wrong]. And he wrote that with allies like this, we may be undone in the end. And this is like [1993]. The piece absolutely holds up.

And then [progressive censors] have moved just about as far as you can go without imposing the death penalty—i.e. life in prison for mere speech. So I think it’s a significant moment. I hope we look back on it as the peak of madness when it comes to legislation that would infringe on free speech, but we’ll see.

J.K.: Well, that’s Canada’s role in the world right now. Apparently we provide cautionary tales for everybody else. So people like you can point to us and say: “What they’re doing… Don’t do that.”

Conor Friedersdorf, thanks so much for being on the Quillette podcast.

C.F.: Thanks for having me.