Music

Leonard Bernstein Deserved Better Than ‘Maestro’

Netflix somehow managed to turn the most talented, beloved, and complex American musician in history into a two-dimensional domestic villain.

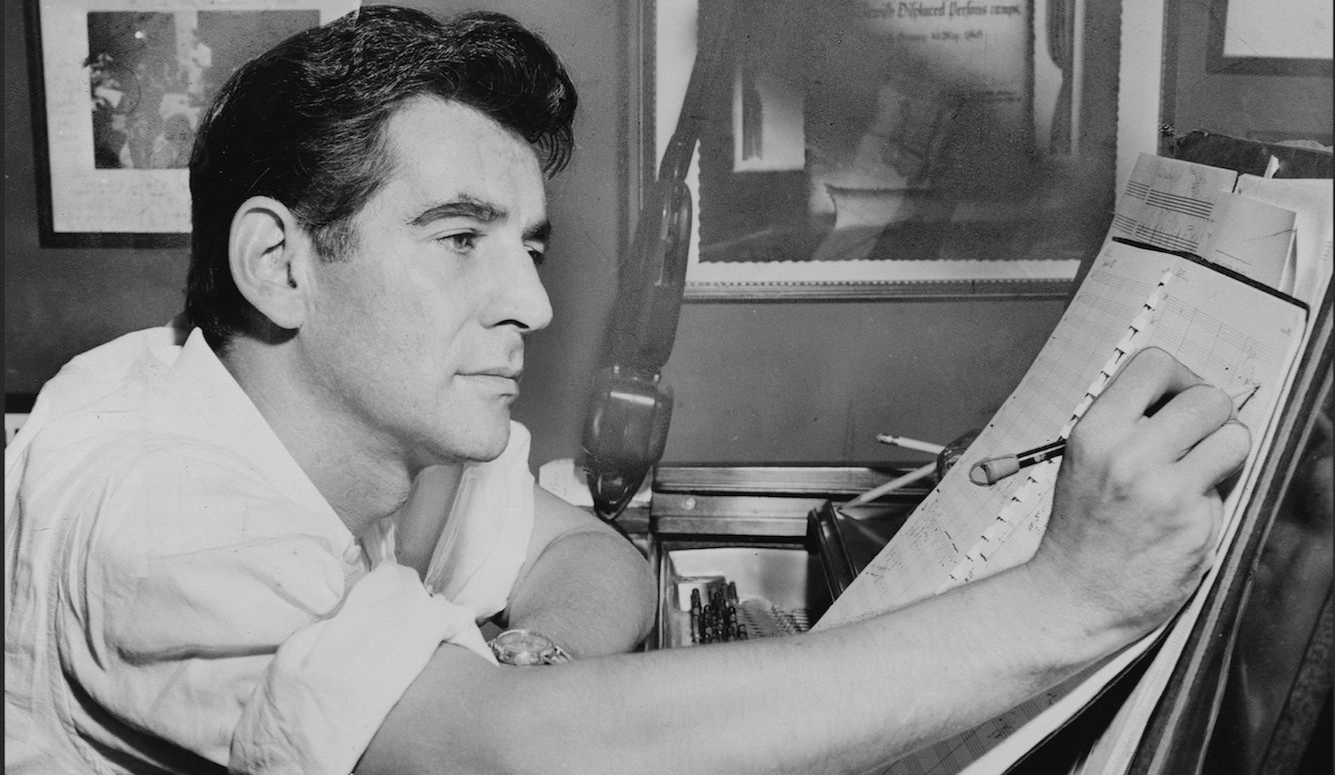

American musician Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990) was, by any measure, an extraordinary talent—as composer, conductor, pianist, and teacher. He came of age in the 1940s, at a time when America was a safe haven for European musicians in flight from the Nazis. Yet Bernstein was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, not Berlin or Vienna, or even New York City (which became his lifelong home as an adult). His rise to international fame showed, for the first time, that the United States could produce music on par with the finest artists of Europe. Whether composing the irresistibly stylish music in West Side Story (with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and a book by Arthur Laurents), or conducting Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 on Christmas Day, 1989, upon the fall of the Berlin Wall (less than a year before his death), Bernstein personified musical excellence.

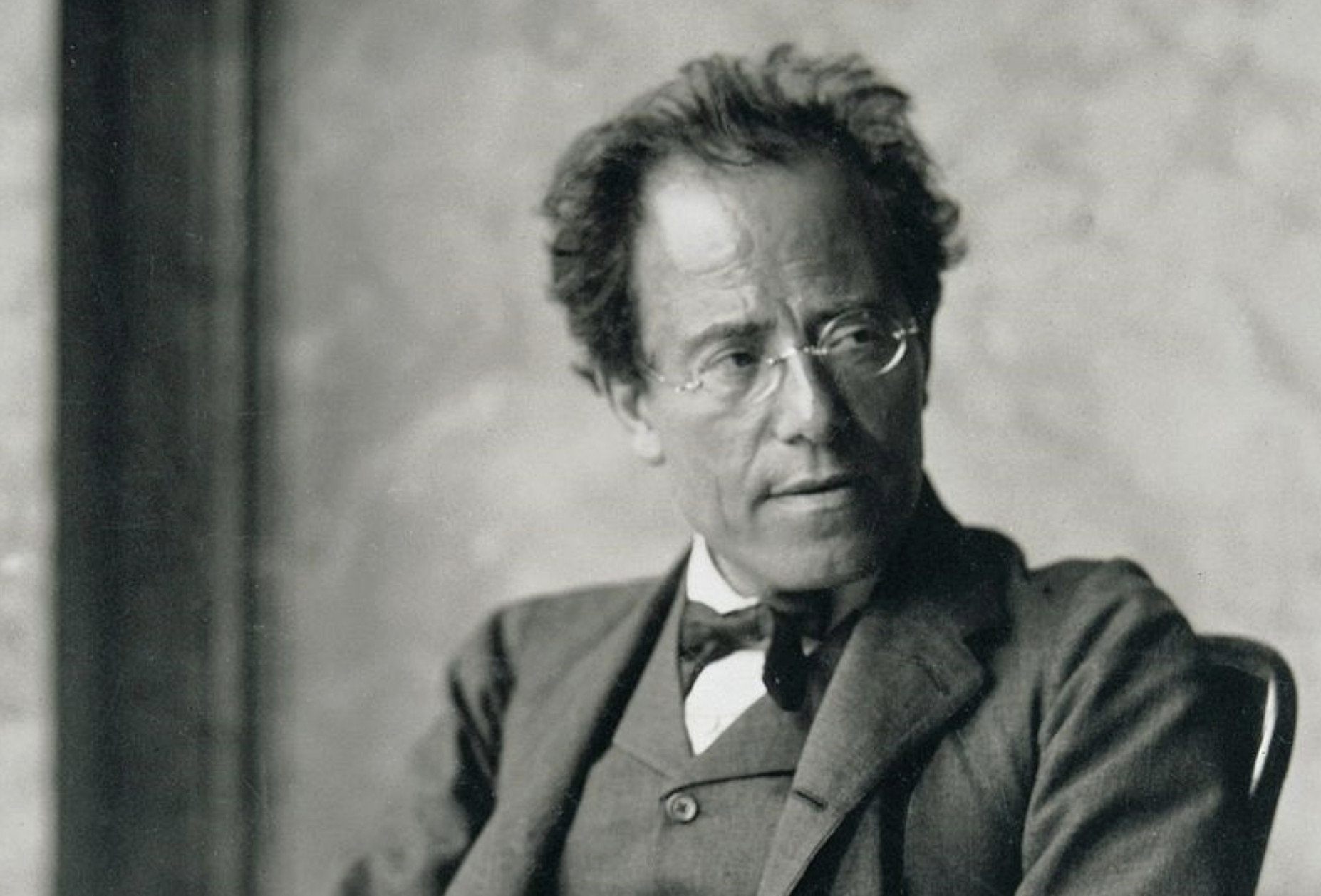

Bernstein the conductor was the first Bernstein whose art I came to know. My earliest memory, in this regard, was familiarizing myself with his phenomenal recordings of the eccentric, groundbreaking, difficult, thorny and (at times) impossibly gorgeous symphonies of the Austro-Bohemian Jewish composer Gustav Mahler (1860–1911).

In music, there are certain composers whose music—like that of Beethoven—has been part of the classical canon for many generations. But Mahler, who was famously underappreciated during his lifetime, is not in that category. Until the 1960s, he still occupied a mere niche in the musical world, being celebrated mostly by a relatively small group of aficionados.

Yes, he was acknowledged as a great conductor, but his compositions were considered too esoteric, too folk-inspired, too difficult to play; in short, too weird. He famously said that he was “thrice homeless, as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, as a Jew throughout the world—always an intruder, never welcomed.” But he knew his time would come, and thanks to Bernstein, it did.

Several of Mahler’s pieces now enjoy iconic status—none more so than the slow-moving Adagietto from his epic Symphony No. 5, which achieved popular acclaim in part thanks to its prominent inclusion in Luchino Visconti’s 1971 film, Death in Venice (Morte a Venezia). That Adagietto remains strongly associated with Bernstein, who’d performed it three years earlier, during Robert F. Kennedy’s funeral mass.

But while Bernstein illuminated Mahler, Mahler also, in a way, illuminated Bernstein—for it is when listening to Bernstein discuss and perform Mahler’s work that I mostly fully understand the degree to which Bernstein was able to fully inhabit the music he conducted.

Bernstein’s influence was so enormous that it pushed beyond the boundaries of music, shaping our wider culture, and even politics—as with this Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra performance of Symphony No. 5, conducted by Bernstein in 1971.

On the surface, it just looks like any other concert. But consider that, from the interwar period on into the 1970s, the Vienna Philharmonic hadn’t played Mahler’s symphonies with any regularity. The country’s cultural establishment had harboured animus toward Mahler on the basis that his compositions evoked a “Jewish” sound. Among German-speaking critics, this line of attack predated the Nazis, as when Rudolf Louis wrote in 1909, “Aber sie ist mir widerlich, weil sie jüdelt”—“it is repulsive to me because [the music] acts Jewish.”

During rehearsals of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, Bernstein became frustrated at the failure—or perhaps reluctance—of these Vienna musicians to evoke the folksy klezmer-inflected character of Mahler’s style. At one point, he scolded the orchestra—the same Philharmonic Orchestra that Mahler had once conducted—with the words, “This is not Mahler.”

It would have been an amazing scene to observe: Just a quarter century after the Second World War had ended, here was an American Jewish conductor teaching one of the most distinguished orchestras in the German-speaking world how to play—or perhaps accept—their own native music. This is the liminal space between music and history.

Many artists are cranky misanthropes who personify the adage, “never meet your heroes.” The opposite was true of Bernstein, who loved educating others about music. While he died long before my own professional music career began, many of my teachers and mentors played with Bernstein or studied under him, and they regaled me and my classmates with stories about—and lessons from—this larger-than-life figure. To this day, Bernstein still inspires me through musical time capsules uploaded to YouTube; and I have found him to be a more compelling, charismatic, and insightful speaker on the subject of music than anyone else I’ve heard.

He changed music education with his legendary Young Peoples’ Concerts at the New York Philharmonic. In 53 performances spanning fourteen years, Bernstein spoke disarmingly to an audience of children, on grown-up topics such as Jazz in the Concert Hall and The Latin-American Spirit. He also addressed abstract subjects such as What Does Music Mean? His lectures were so successful that they were broadcast by CBS at prime time, translated into other languages, and syndicated to dozens of other countries. (For those seeking a sample, here is a complete broadcast from 1962 on the topic of What is a Melody?)

Bernstein also gave a series of six lectures at Harvard University in 1973, titled The Unanswered Question, starting with an incredible instalment called Musical Phonology. These were aimed at a sophisticated specialist audience. Yet such was his natural audience appeal that even these more esoteric lectures were adapted into a book, broadcast on PBS, and went on to rack up millions of views on YouTube.

Bernstein has been critiqued as a showman who used gimmicks to popularize classical music. But his effusiveness was really just a reflection of his irrepressible love of music—which could manifest itself in impish innovations, as in this video of the final movement of Haydn’s Symphony No. 88, in which Bernstein drops his arms and conducts the orchestra with his face. In another well-known performance, this time of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 17, Bernstein found a way to both conduct the orchestra and perform as a piano soloist.

Given my appreciation of Bernstein’s genius and historic legacy, I had high hopes for Netflix’ recently released biographical drama from director Bradley Cooper, Maestro—billed as a “towering and fearless love story chronicling the lifelong relationship between cultural icon Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre” (played by Cooper and Carey Mulligan respectively).

Was it any good? The fact that the first extended scene about music didn’t come till about 90 minutes into the two-hour film should be enough to supply you with your answer. By confining the plot to a small part of Bernstein’s personal life, Cooper somehow managed to turn the most talented, flamboyant, beloved, successful, and complex American musician in history into a two-dimensional domestic villain.