Some of the most celebrated novelists of the past half-century died this year, including Cormac McCarthy, A.S. Byatt, Martin Amis, D.M. Thomas, Milan Kundera, and Kenzaburō Ōe. The deaths of those writers justifiably generated numerous tributes and appreciations in the pages of the world’s most venerable newspapers and magazines. I would like to take time here to remember three writers who also passed away in 2023 but whose deaths did not receive the attention they deserved.

Gabrielle Carey (1959–2023)

Australian novelist Gabrielle Carey, who died in May of this year, was born on January 10th, 1959. At the age of just 20, Carey and her close friend Kathy Lette published a scandalous autobiographical novel titled Puberty Blues about the exploits and misadventures of under-aged girls who strayed into the mostly masculine world of mid-20th-century surf culture. In discussions of Australian literature, Carey and Lette’s provocative coming-of-age tale is often compared to The Catcher in the Rye.

Both authors were born in Sydney (Lette was just two months older than Carey), and their novel is set largely in Cronulla, one of the city’s beachfront suburbs. Girls were welcomed into surfing groups so long as they fetched food and towels, ran errands, and made themselves available for any kind of sexual activity the boys demanded. The novel’s 13-year-old protagonists, Deb and Sue, duly endure a series of often degrading experiences at the hands of the surfers they long to call their boyfriends. Sadly, their home lives are so dull that these experiences strike them as an exciting change.

The novel opens with this:

When we were thirteen, the coolest things to do were the things your parents wouldn’t let you do. Things like have sex, smoke cigarettes, nick off from school, go to the drive-in, take drugs and go to the beach.

The beach was the centre of our world. Rain, snow, hail, a two-hour wait at the bus stop, or being grounded, nothing could keep us from the surf. Us little surfie chicks, chirping our way down on the train. Hundreds of us in little white shirts, short-sleeved jumpers, thongs and straight-legged Levis covering little black bikinis. We flocked to the beach. Cheep. Cheep.

Carey and Lette didn’t sugarcoat surfie chick life, and the frank discussions of sex (usually referred to as “rooting”) made the book notorious from the moment it was published. The most painful scenes occur when Deb, the narrator, describes her attempts to give some boy or other the sex he wants, despite the fact that her 13-year-old body clearly wasn’t yet ready to be used in this way.

As Deb explains:

You didn’t necessarily have to like a guy to go out with him. If he was part of the gang and he chose you, you felt privileged. You’d go out with him about three times… well, you wouldn’t actually go out with him. You’d go out with his gang to a party and when everyone else paired off, for a pash [make-out session] on the front fence, or a finger behind the Holden [an Australian model of vehicle], or a “tit-off” down the other end of the hall nearly in the linen press. You wouldn’t talk, you’d just “be with” him. From that night on, you’d know you were going around with him.

The various beaches in Sydney are ranked according to their desirability. South Cronulla is the least prestigious of the beaches. North Cronulla is slightly more attractive. But the real goal of every surfie chick was to attract a boy who surfed at Greenhills, the most exclusive beach in the area. The more desirable the surfing spot, the more the girls were willing to do to get there. Here’s Deb again:

At South Cronulla we’d let the boys “tit-us-off” and occasionally get a hand down our pants. At North Cronulla we’d progressed to dry roots. When we graduated to our new gang at Greenhills, we’d hit the big time. It was time for the spreading of the legs and the splitting up the middle.

You had to “go out” with a guy for at least two weeks before you’d let him screw you. You had to time it perfectly. If you waited too long you were a tight-arsed prickteaser. If you let him too early, you were a slack-arsed moll. So, after a few weeks, he’d ask you for a root, and if you wanted to keep him, you’d do it.

While Deb sits in the front seat of the surfers’ panel van awaiting her turn to be deflowered, she listens “to the suppressed screams of agony as Sue lost her virginity to Danny in the back. That’s the way it goes for girls. Every car in the parking lot was doing it… the panel-van bop. Then it was my turn. I couldn’t say no. Bruce had picked me out of all the other girls. Bruce was the top guy of the gang. Even better than Darren Peters. He was the eldest. He had a car, a job, money, and the biggest prick.”

Hip and profane, Puberty Blues made instant celebrities of its two young authors, and for a while they wrote a column together for the Sun-Herald under the byline “Salami Sisters.” But soon they drifted apart, and fell out of contact for 20 years. Although they both went on to write more books, they never again collaborated on one. Carey wrote one solo novel in 1994 titled The Borrowed Girl and then retreated into obscurity. The pair reunited for a TV profile in 2012, when Puberty Blues was being adapted as an Australian TV series.

A 2020 profile of Carey by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation notes that: “The public reaction to Puberty Blues was one of outrage and incredulity, and the media hovered over the girls constantly. While Kathy embraced her growing fame, Gabrielle felt a strong urge to escape it. She moved to Ireland, then lived in Mexico for many years before returning to Australia to build a career as a writer and academic.”

I couldn’t find Carey’s cause of death listed anywhere online, but most of the obituaries state that she died “suddenly,” which is often a euphemism for suicide. One of them noted that, “Her death comes just months after she wrote an article revealing that she was ‘terrified’ of turning 64, after her father’s death by suicide at the same age.” In that article, published last December, Carey insisted that she had conquered depression and would not end up emulating her father. Alas, the article has a sort of “whistling past the graveyard” quality to it—it sounds like someone trying to convince herself that everything is fine when, deep down, she knows it isn’t.

As a teenager, Carey dropped out of high school and triumphed over the puberty blues by turning them into art. But decades later, it appears she was unable to triumph over the Boomer Blues that have afflicted many people of her (and my) generation. Having been let go from her university job at the age of 63, she faced an uncertain future armed with very little in the way of financial resources. That’s a great shame because Puberty Blues remains a small masterpiece of English-language popular fiction.

John Jakes (1932–2023)

American author John Jakes died in March of this year, just 20 days shy of what would have been his 91st birthday. He studied creative writing at DePauw University in Indiana and graduated in 1953. From there, he went on to earn a Masters in American Literature from Ohio State University. He began selling stories to pulp magazines in the early 1950s but didn’t achieve true national recognition until the mid 1970s.

Prior to that, he published in a wide variety of pop-fiction genres, including five books featuring a character he called Brak the Barbarian, which clearly owed something to both Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian books as well as to the Bible (the Brak books contain many parallels to the early days of Christianity). In 1972, he wrote Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, a novelization of the film. Then as now, the movie tie-in genre was considered sub-literary and it is likely that Jakes took the job for the money. His career seemed to be petering out.

In 1973, a New York entrepreneur named Lyle Kenyon Engel established a production company that would churn out paperback books in much the same way that poverty-row studios in Hollywood used to churn out films. Engel called the company Book Creations Inc., and enlisted his wife and his son to help him run it. Typically, the Engels would come up with an idea for a series of novels, outline the narratives, sell the idea to a publisher, and only then hire a writer to actually produce the books. Here’s how the New York Times described their operation in a 1979 article:

Mr. Engel, who calls himself a book producer, runs what is reputed to be the most successful “fiction factory” in the world. In three Tudor‐style buildings in Canaan, N.Y., just across the border from Massachusetts, Mr. Engel, his wife, his son, several editors and a librarian will create in 1979 alone 75 novels for publication by 10 leading paperback houses. More than 300 million books produced by Mr. Engel's company—Book Creations—have already been sold. He thinks up the ideas for the various series (his most famous one—“The Kent Family Chronicles”—has turned up in paperback, hard cover and as several mini‐series on television), sells the series to a publishing house, then assigns one of the professional writers under contract to him to write the book from his outline. For his share in the creative and selling process, Mr. Engel gets 50 percent of the royalties.

In 1972, Jakes was churning out a novelization of an ape movie for which he was paid a flat fee of $1,500. A year later, Lyle Engel hired him to write the Kent Family Chronicles series, which would go on to become one of the publishing sensations of the decade. In 1975, Jakes became the first author ever to have three books on the New York Times bestseller list in the same calendar year. By the end of the decade he was reported to have earned more than a million dollars in royalties from the Kent Family Chronicles.

The books were timed to coincide with America’s 200th birthday, and while Jakes had plenty of competition, few writers profited from the Bicentennial fiction boom as much as he did. The eight volumes in his Kent Family Chronicles, published between 1974 and 1979, were all massive bestsellers. And they deserved to be—Jakes was already well-versed in American history, having already produced numerous Westerns and other historical fictions under the pseudonym Jay Scotland, and the Kent Family Chronicles benefitted from his familiarity with his country’s storied past.

As far as I know, no contemporary publisher is producing a comparable series of novels to mark America’s upcoming 250th anniversary in 2026. Nowadays, a book series intended to celebrate the colonists who threw off the yoke of British rule is likely to attract derision from American academics and critics convinced that their country’s creation was simply an act of heinous dispossession. A splashy new reprint edition of the Kent Chronicles also seems unlikely for the same reason.

But Jakes wasn’t a mindless celebrator of all things American. The title of the first book in the series—The Bastard—indicates that Jakes didn’t intend to tell a story about saintly American colonists. He and Engel wanted the series to provide a warts-and-all portrait of the men and women who fought for American independence. The second book in the series, called The Rebels, features a character named Judson Fletcher, who is a drunk, a womanizer, and a rapist. He kills a man in a duel and causes the man’s niece to commit suicide. Nonetheless, Fletcher is a complicated and, at times, admirable character. When his best friend is killed by an uprising of black slaves, he defends the action to his plantation-owning father, causing him to be tossed out of the family home. The series is a chronicle of America’s founding generation, but not necessarily a celebration of it.

“I feel a real responsibility to my readers,” Jakes told the Washington Post in a 1982 profile. “I began to realize about two or three books into the Kent series that I was the only source of history that some of these people had ever had! Maybe they'll never read a Barbara Tuchman book—but down at the K mart, they'll pick up one of mine.” And as the Post notes, “Millions did, and in the process developed a ravenous appetite for the fastest growing genre in publishing: the paperback original, multi-volume family historical saga.”

After eight novels, Jakes decided to sever his connection with Engel. He was now a big enough name in the publishing world that he could demand huge advances. He could also leave behind the world of paperback originals and insist that his future novels receive the full hardback treatment. He then produced a trilogy of novels about the Civil War that became massive bestsellers. The first volume in that series, North and South, was the eighth bestselling novel of 1982, one notch below Stephen King’s Different Seasons. Love and War was the fourth bestselling novel of 1984. Heaven and Hell was the ninth bestselling novel of 1987, one notch above King’s Eyes of the Dragon. The last of Jakes’s monster bestsellers (though he produced plenty of other successful novels) is my favorite, California Gold—a massive standalone historical novel that was the ninth bestselling novel of 1989. His final novel, The Gods of Newport, was published in 2006.

John Nichols (1940–2023)

John Nichols, who died in November at the age of 83, had a little in common with both John Jakes and Gabrielle Carey. Like Carey, his first published novel (he claimed it was the eighth he’d written) was completed when he was relatively young (23). When it appeared in 1965, The Sterile Cuckoo also drew comparisons with The Catcher in the Rye (or at least Alan J. Pakula’s 1969 film adaptation did). And like Jakes, Nichols was best-known for writing a series of novels about American rebels.

The Milagro Beanfield War, Nichols’s best-known novel and the first in his New Mexico Trilogy, was published in 1974, the same year as Jakes’s The Bastard. He followed it with The Magic Journey in 1978 and The Nirvana Blues in 1981. All three books bear some resemblance to Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang (published in 1975, so probably not a huge influence on Nichols) insofar as they all deal with people willing to go to extreme lengths to protect America’s desert southwest from the ravages of capitalism and overdevelopment.

Nichols claimed he wrote a novel a year and was able to publish only about a quarter of the books he actually completed in his lifetime. This sounds like typical writerly bluster, but this bizarre seven-minute video suggests that, if anything, he may have been understating his productivity:

I first discovered Nichols’s work when I read The Magic Journey at the age of 25, and I thought it was the most brilliant book I’d ever read. It begins in 1930 and spans 40 years in the life of Chamisaville, a fictional New Mexico town probably inspired by Taos. It opens with a literal bang, when a cache of illegally acquired dynamite accidentally explodes and exposes a mineral spring under the town center. A handful of greedy entrepreneurs decide to exploit the discovery and turn it into a tourist destination, and soon the place is rife with development, dollars, and environmental destruction. Decades later, April McQueen, the daughter of the man who hauled the dynamite into Chamisaville, will band together with a small group of idealistic radicals and try to undo the damage wreaked by her father and his cronies.

Prior to discovering The Magic Journey, I had read The Monkey Wrench Gang, Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle, and plenty of other novels about left-wing social activists trying to save the world. But none of them spoke to me as directly and movingly as The Magic Journey did. I’m still not sure why I enjoyed it so much. I was never an activist, nor have I ever been all that interested in environmentalism. Politically, I’ve always been a rather middle-of-the-road Democrat. And I could tell from his books that Nichols was as leftwing as you could get without being a terrorist of some kind. But something about The Magic Journey spoke to me.

At the time, I felt very alone in my love of this book, because I never encountered another living soul who had read it. Today, thanks to the internet, I can go online and find a handful of other superfans. A review at Goodreads begins: “I believe this is probably my favorite book,” and an Amazon review describes it as “the greatest book ever.” After re-reading The Magic Journey several times in the mid-’80s, I went back and read all of Nichols’s earlier novels, including The Sterile Cuckoo, The Wizard of Loneliness, and The Milagro Beanfield War. I continued reading every novel he published until about the mid-1990s, and while I enjoyed most of them, none of them had the same effect on me that The Magic Journey did. If I re-read it today I would almost certainly discover that it is not the masterpiece I remember, so I prefer to hang on to the memory of how it made me feel instead.

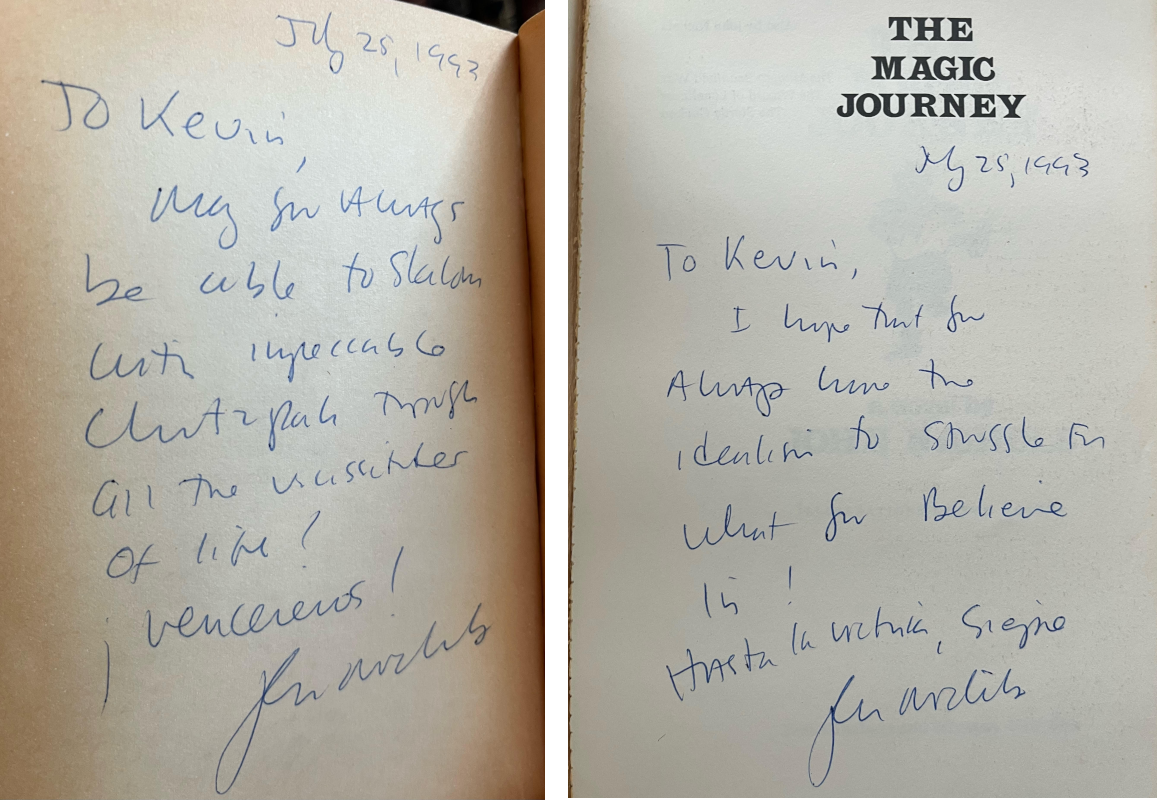

In 1993, a friend of mine, novelist Karen Joy Fowler, mentioned that she was going to be teaching at a writers’ conference with Nichols that summer. I was still enough of a fan that I asked her to take him a couple of novels to autograph. I supplied her with my dogeared trade-paperback copy of The Magic Journey, as well as a cheap mass-market paperback copy of The Milagro Beanfield War. I was broke at the time (a chronic condition, alas) and couldn’t afford to purchase hardback books. Occasionally, I have been sneered at by writers when I showed up at their book signings bearing tattered paperbacks, so I knew I might be putting Karen in an awkward position. I needn’t have worried. Karen returned the books to me, warmly and amusingly inscribed. Dated July 25th, 1993, the inscription in The Milagro Beanfield War reads:

Kevin,

May you always be able to slalom with impeccable chutzpah through all the vicissitudes of life.

Venceremos!

John Nichols.

(“Venceremos” is Spanish for “We will win.”) Inside my copy of The Magic Journey he wrote: “I hope you always have the idealism to struggle for what you believe in!”

Now that I’m 65, I suspect that Nichols might be disappointed in me. I’ve spent my adult life mostly just struggling to keep a roof over my head, so idealism hasn’t played much of a role in my daily grind. And only rarely have I found myself slaloming with impeccable chutzpah through all the vicissitudes of life. Most of the time it has been a somewhat arduous trek. But even when it has been a complete slog, I’ve always been able to find solace and joy in the works of popular-fiction writers like John Nichols, John Jakes, and Gabrielle Carey. They will be much missed.