Second World War

Chasing the Ice Moon

A new book describes the crackpot anthropological theories that Nazis used to justify their belief in Aryan racial superiority.

“Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past,” is one of the more famous slogans coined by George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The 1949 novel was a dystopian satire of totalitarian politics and thought control. But this particular adage had real-life application in the propaganda strategies employed by both the USSR and Nazi Germany.

Of particular note in this respect was the Ahnenerbe (Full name: Forschungsgemeinschaft Deutsches Ahnenerbe, or Research Society for the German Heritage of Ancestors), a body founded by the Nazis’ Schutzstaffel wing (better known as the SS) to perform anthropological, archaeological, and racial research aimed at proving the supposed superiority of the “Aryan race.” As the whole notion of there being any such thing as a “pure” Aryan race was always a fiction, the only way for Ahnenerbe scientists to fulfill their task was by making things up.

The leader of the SS throughout the Nazi period, Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945), is most infamous for being an architect of the Holocaust. At his command, the SS also committed countless other atrocities, including the use of concentration-camp prisoners for slave labour, and staged massacres of Romani, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and gay men and women. In part, it seems, his monstrous crimes were animated by a belief in the so-called völkisch movement, a mash-up of German ethno-nationalism, folk mysticism, and antisemitism. Adherents embraced a wide variety of bigoted beliefs, but generally held in common a reverence for the ancient German Volkskörper (“body of the people”) and a belief that Jews were an alien contaminant within that body. Needless to say, many Nazis were drawn to its precepts.

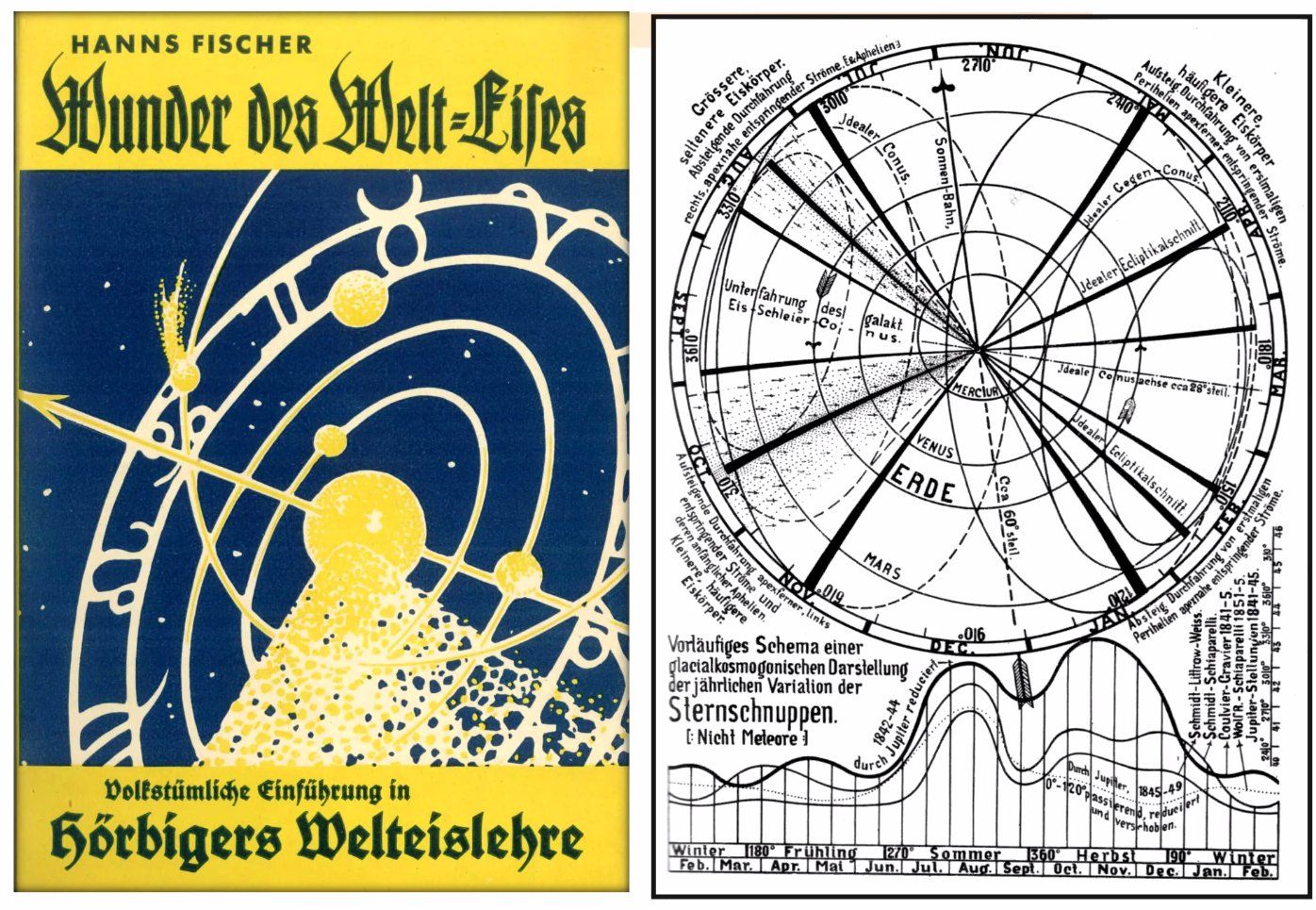

For all the Nazis’ pseudo-scientific claims about racial purification, the völkisch movement was suffused with many bizarre, crankish, and conspiratorial ideas that today might be associated with the most disreputable fringes of the “New Age” movement. Himmler himself was interested in whether Aryans came from outer space, and the myths of Atlantis. He seemed to imagine that the Norse gods might have once been real, racially superior individuals possessed of amazing powers and super-technologies; and assigned credence to a strange cosmological idea called Welteislehre (World Ice Theory), which taught that ice was the basic substance out of which the universe was constructed. And yes, as in an Indiana Jones movie, he wanted to uncover the Holy Grail.

These ideas didn’t die with the defeat of the Nazis, unfortunately. As I found out while writing my new book, Hitler’s & Stalin’s Misuse of Science, they’ve been adapted and reinvented in unlikely new forms.

The Ahnenerbe grew out of an earlier organisation, the Herman Wirth Society. Wirth (1885-1981) was a Dutch-German amateur scholar who identified as a “pan-German,” making him predisposed to welcome Hitler’s invasion of the Netherlands. As Wirth saw it, this wasn’t so much an invasion as it was a confirmation of his long-held völkisch view that the Germans and Dutch were one people destined for reunification.

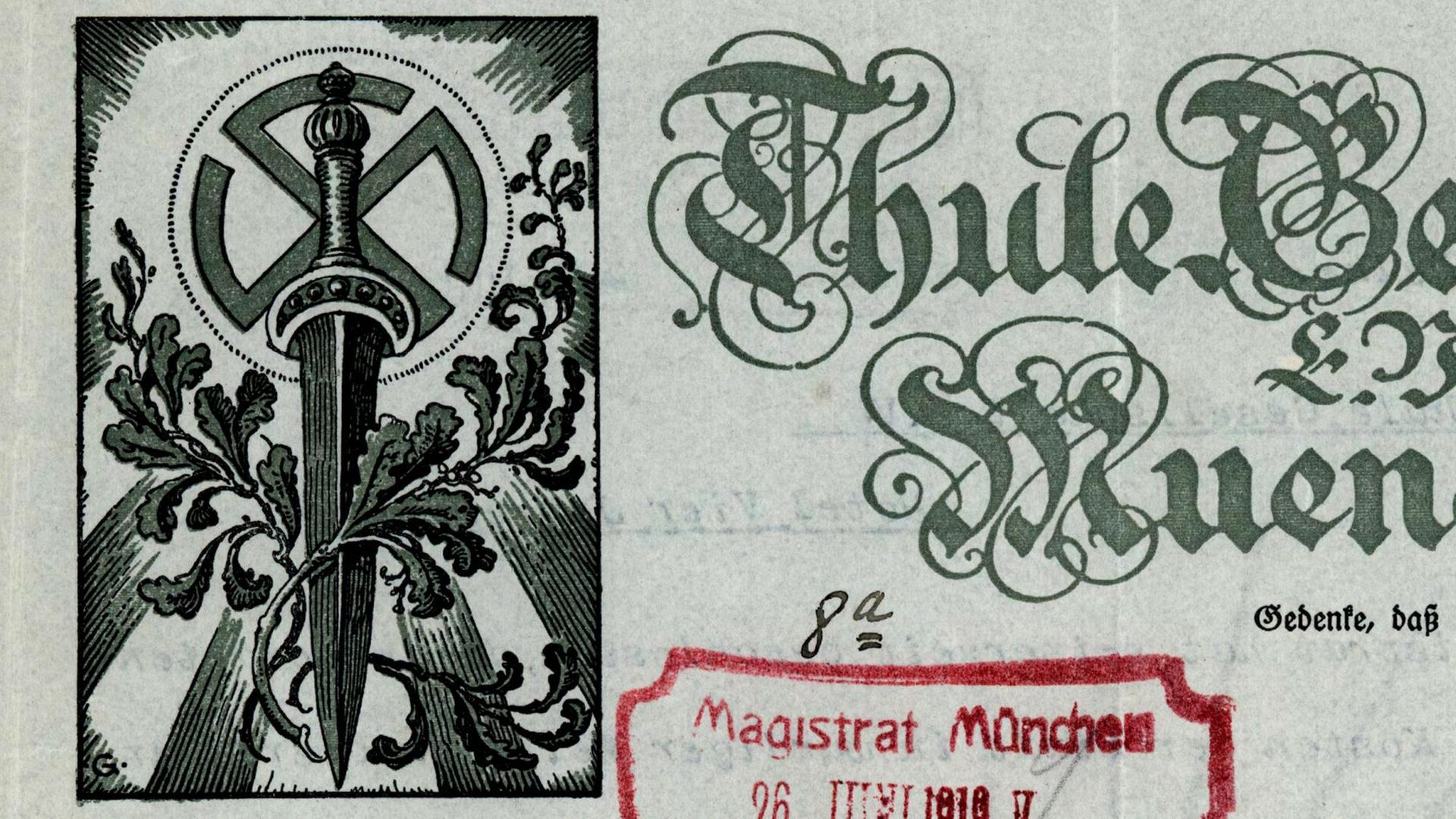

Like Himmler, Wirth was fascinated by not only Atlantis but also Thule, a fictional prehistoric Arctic ice-continent upon which the original frost-hardened Aryan race was supposedly born (a notion still advanced today by certain ultra-nationalist figures). Such ideas, fantastical as they were, presented an obvious appeal to racists who refused to believe that they, along with all the world’s peoples (Jews included, of course), emerged from the same original genetic origins. What they wanted was a separate, parallel, race-segregated backstory that had Aryans evolving in their own race-controlled evolutionary silo.

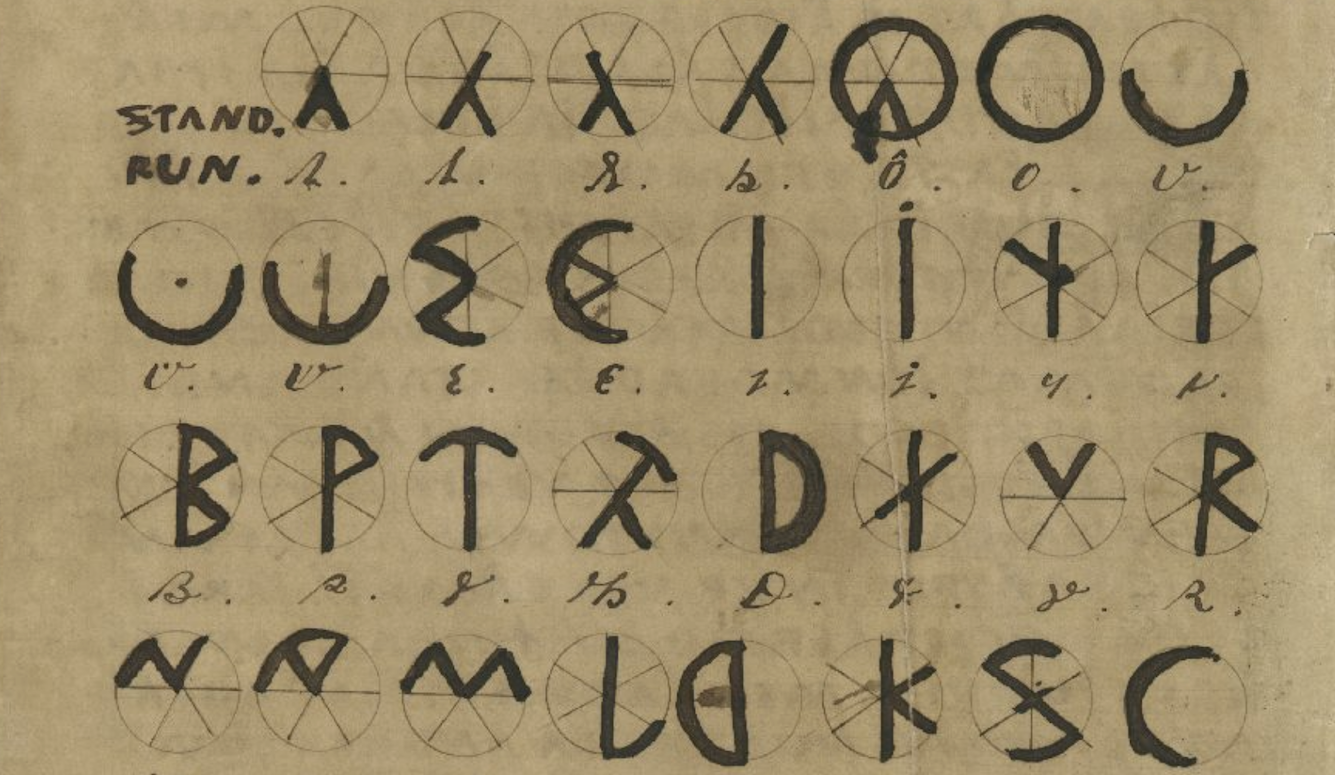

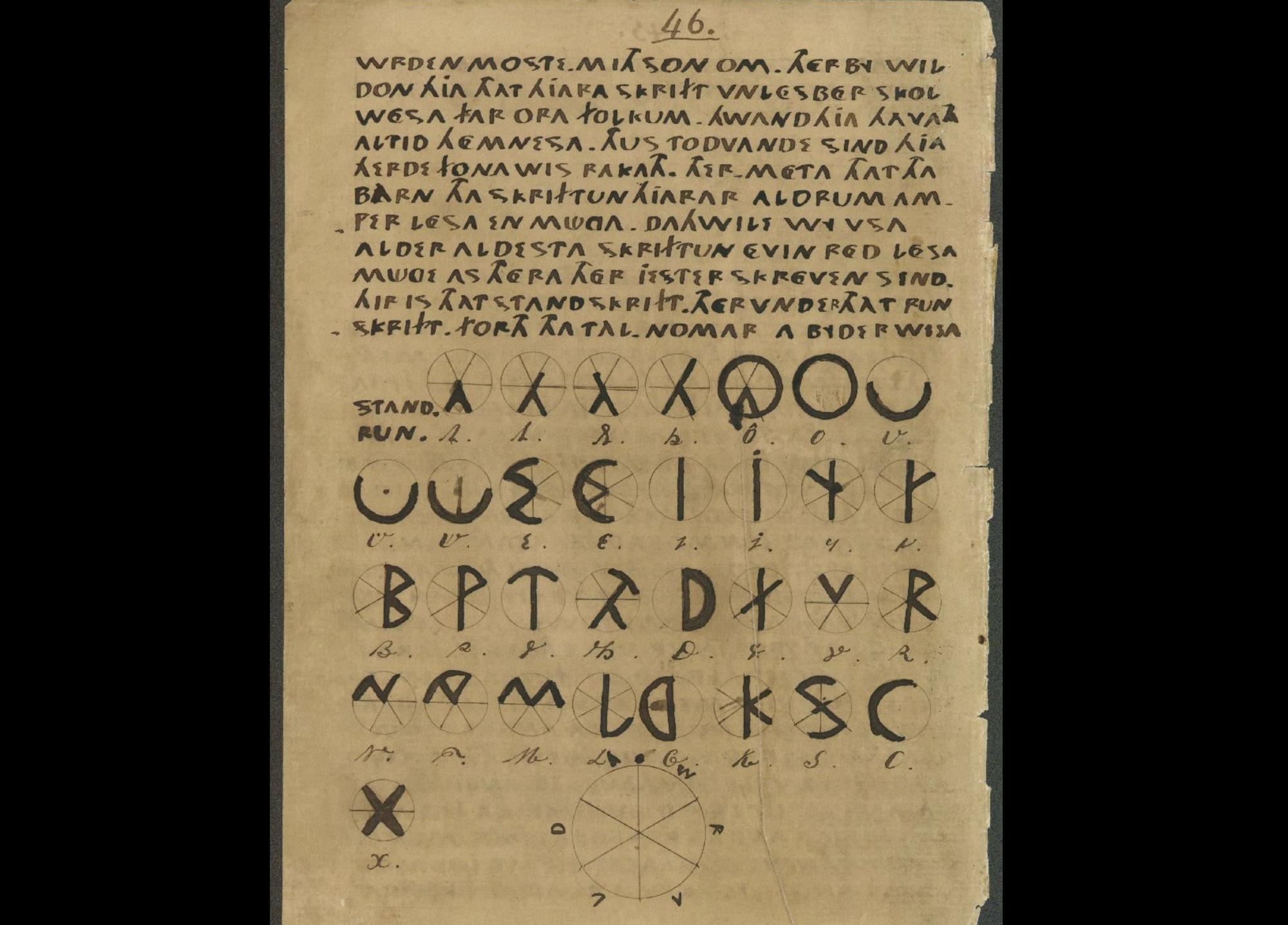

These belief systems were the stuff of bad science fiction and D-list comic titles. Wirth believed, for instance, that ancient Ice Age Aryans had once carved their astronomical moon-knowledge into rocks, thus creating the basis for their later runic alphabet. Wirth’s principal method of inquiry was to rely on the receipt of mystical visions. Following World War II, one Germanic carving of a prehistoric “Earth Mother” he’d unearthed turned out to be 1950s graffiti depicting a well-endowed Marilyn Monroe. Ancient cult symbols of birds and butterflies discerned on one cave wall, likewise, turned out to be the emblems of a local Scout group.

Wirth served as the Ahnenerbe’s original Honorary President from 1935 onward, when the organisation was founded. And it says something about how unscientific his methods were that even the group’s membership—men who spent their days hunting the Holy Grail—eventually felt compelled to remove him from his post (though that didn’t stop Himmler from continuing to fund some of his “research”).

In the worst tradition of horseshoe theory—by which extremists on both ends of the political spectrum come to embrace common claims and methods—Wirth betrayed himself as something of a postmodernist. “The time is now past when science believed its task was to search for the truth, such as it is,” he once declared. Instead, science’s supposed task was to “awaken” the sleeping German soul, which, “like the morning dawn,” would “light a new day” for the volk.

As Nazism was formally anti-Christian (Jesus being Jewish and all), Himmler and many of his fellow travellers felt the need to create a new national faith, possibly by resurrecting the old gods of the Norse pantheon. The problem was that little was actually known about these deities, as the ancient Nordics left little in the way of written records.

This did not deter Wirth, who argued that ancient Germans had invented the art of writing. Moreover, their ancient writings provided the instruction manual required for Germans to escape the corruptions of modern culture. His writings had titles such as What Does It Mean to Be German? A Look Towards Self-Understanding Aided By Ancient Spiritual Knowledge. This was the backward-looking message at the core of the völkisch movement: The moral blueprint of Germany’s future lay in its (supposedly) sacred past.

In her 2006 study of the Ahnenerbe, The Master Plan: Himmler’s Scholars and the Holocaust, historian Heather Pringle analysed Wirth’s unlikely rise to prominence. In 1909, he landed a position as a lecturer in philology at the University of Berlin, where he held magic-lantern shows and concerts featuring early Dutch folk music. Wirth dressed up as a medieval singer in green velvet and performed with the aid of an adoring young German lute player disguised as a fairy-tale princess. That woman, Margarethe Schmitt, became his wife. She reportedly thought her husband to be “the coming Messiah.”

After joining the Nazis in 1925, Wirth accumulated young acolytes who would dress in alpine-themed shorts and attend gatherings to hear their “dear father” preach the benefits of country living, vegetarianism, and abstinence from tobacco. He encouraged the establishment of völkisch rural communes where farmer-scientists would live together in harmony with Nature. The parallels with modern-day Indigenous-awakening political reveries are hard to ignore.

Such gatherings could be very odd, and included dinner-table meals during which Wirth and his wife would sit communicating telepathically with one another in total silence. It was through another such (self-described) psychic that Wirth was first introduced to Himmler in 1934: Gesine von Leers, the wife of a leading Nazi propagandist. She claimed to be the reincarnation of a Bronze-Age German priestess, a fact she advertised by wearing fake jewellery recalling this historical period.

Like Gesine and his own supposedly clairvoyant wife, Wirth claimed to possess paranormal powers. He explained to Himmler that, whilst wandering gloomily through the Dutch region of Friesland during the 1920s, pondering the collapse of Nordic civilization at the hands of Jews (as one does, apparently), he enjoyed a sudden moment of insight. As discussed by David Barrowclough in his 2016 work Digging for Hitler, Wirth found that Frisian farmhouses contained many carved decorations in simple shapes such as stars, hearts, diamonds, crowns, shamrocks, and crosses. He wondered: What if such items were not mere pretty patterns, but were actually forgotten remnants of a form of primeval Germanic hieroglyphics, from which all later styles of picture-writing, like those of ancient Egypt, had subsequently been developed?

As you might have guessed, the hypothesis was entirely baseless. The “hieroglyphs” that had attracted Wirth’s attention were just random ornamental shapes. But to Wirth, they were records of the ancient Aryan race’s origins in a Thule-like Arctic homeland two million years ago.

In the style of L. Ron Hubbard’s space operas, Wirth imagined an all-female ruling-caste of warrior-queens living within circular castles. Glaciation had forced them to migrate, he theorized, and so they set out to a new colony—in Atlantis, naturally, because where else?—in ships shaped like giant swans. Wirth even claimed he’d found geological records that proved his case. He referred sceptics to a supposedly ancient text known as the Ura-Linda Chronicle, which contained the history of circular fortress-dwelling matriarchs. Not surprisingly, the “Chronicle” turned out to be a hoax written to satirize absurd nationalistic fables of exactly the type Wirth himself was peddling.

So when Himmler sought information about the old pagan beliefs of his noble ancestors, Wirth was easily able to supply it—by making it all up. This did not mean he was consciously lying, per se. Legitimate scholars of the era felt he was suffering from a sort of “holy insanity,” much like a religious mystic who claims to channel the words of God. (This is about the time when other Ahnenerbe members felt Wirth was tarnishing their altogether more plausible ideas about ice moons and the search for the chalice used by Christ at the Last Supper.)

Unlike Himmler, who bit into a cyanide capsule after being captured by British troops (and was then thrown into an unmarked grave), Wirth survived the war and its aftermath. He posed as a victim of the Nazi regime (even while sometimes defending it), and continued to dabble at archaeology. His methods were so amateurish and inept that the Swedish government eventually banned him from examining any more of that country’s primeval rock art, on the grounds that Wirth kept accidentally damaging it. He died in 1981, still a minor cult hero among neo-Nazis. To this day, antisemites and members of some extreme right-wing groups cling to the hope that he left behind a foundational text that will reinvigorate their hateful movements.

It’s easy to see Wirth and his theories as a joke. But given the way his pseudoscience infused the beliefs of real Nazis who did real evil, it’s a very dark joke. And it shouldn’t be surprising that Wirth’s ideas have been taken up today by some Russian ultra-nationalists. When (formerly) fringe politicians come to power, so often do fringe scientists.

But fringe right-wing bigots aren’t the only individuals who’ve channelled such beliefs. In a twist that Wirth and his Nazi benefactors would no doubt find horrifying if they were still alive, his combination of crank historical research and racial supremacism has been adapted by some black Afrocentrists, who situate the origin of the ancestral supermen of yore not in Atlantis but Africa.

The Afrocentrism movement began as a reasonable corrective to excessively white-centred views of world history promulgated by Western historians. But it didn’t take long for its precepts to become co-opted by extremists, who turned it into an inverted version of the Ahnenerbe. In this variation, it is blacks, not “Aryans” whose ancestors (in Black Egypt) are the biologically superior progenitors of all the world’s great technologies and cultural adaptations.

The most notorious Afrocentrist has surely been Leonard Jeffries (b. 1937), once the chair of Black Studies at the City College of New York. A good account of Jeffries’ unusual methods can be found in Richard M. Benjamin’s aptly titled 1993 essay, The Bizarre Classroom of Dr Leonard Jeffries. Just as Wirth dressed in green velvet as a medieval meistersinger, so did Jeffries don traditional flowing African robes to deliver his lectures, which he often began by mouthing the Egyptian greeting of Hotep!

One Afrocentrist theme that would draw approval from Wirth is antisemitism: While Wirth would have disagreed with Jeffries about the black-white racial pecking order, the two men both described Jews as pests. In 1991, Jeffries made headlines after giving a speech blaming Jews and mafiosi for negatively depicting blacks through “Sambo images” in Hollywood movies. “We’re pinpointing their relationship,” he went on to say of the supposed global Jewish-mafia-whitey conspiracy: “We’re putting it into our African computer; the document is being prepared.” (City College’s subsequent efforts to remove Jeffries from his post led to a long-running legal battle that the disgraced academic ultimately lost.)

Rewriting history in the same obsessive fashion as Wirth, Jeffries proclaimed that “a false Greece” had been created by white men such as George Washington, which served to cover up the truth of how Greeks “went to learn at the foot of the Africans” in Egypt. In the fateful 1991 speech that would destroy his career, Jeffries also rather ominously told fellow educators that he and others were “preparing ten volumes dealing with the Jewish relationship with the black community in reference to slavery, so we can put it in the school system.”

“Whoever controls the history, controls the vision,” Jeffries once said. It’s tempting to see this as a rip-off of the totalitarian slogan from Nineteen Eighty-Four. But given what we know about the kind of ideology he espouses, it’s entirely credible that Jeffries arrived at this epiphany independently.