Israel

The Deadly Logic of Decolonization

Western countries are seen as colonizing nations and imperialists, while foreign autocracies and sectarian extremists like Hamas are perceived as freedom fighters and even forces for good.

When the Khmer Rouge embarked on their genocidal campaign against the Cambodian people in 1975, they aspired to mold Cambodia into a self-sufficient, socialist, agrarian society, emancipated from all foreign influence. Their mission was to usher in a “Year Zero,” which would return the country to an imagined golden age of peasant agriculture and upend society, giving the least privileged power over the most and punishing educated city dwellers, whom they believed had succumbed to the corrupting forces of Western capitalist culture.

If the Khmer Rouge were around today, some of the West’s left-wing commentariat might well applaud their actions as “decolonization.”

The term “decolonization” was historically used to refer to the process through which imperial nations relinquished control over their former colonies, thereby enabling them to attain sovereignty. This happened with the dissolution of the Spanish Empire in the nineteenth century; the disintegration of the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian empires after World War I; and the demise of the British, French, Dutch, Portuguese, and Japanese empires following World War II.

As former colonies gained independence, they also began to develop their own cultures and intellectual traditions, and the academic discipline of postcolonialism sprang up to study this phenomenon. Postcolonialist scholars asserted that European political and economic dominance was accompanied by a Eurocentric perspective that portrayed Western civilization as the pinnacle of human achievement, while unfairly disparaging indigenous culture and knowledge as primitive. In the former colonies, independence often resulted not only in the establishment of new national political and legal systems but also in the revision of educational curricula and a shift in focus away from the Western canon, which featured figures like Mozart, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Hobbes, and Locke.

However, decolonization—whether political, economic, cultural, or intellectual—can go well beyond all of that. For its most zealous advocates, the end goal has always been a tumultuous revolutionary struggle aimed at restoring a precolonial culture and society—essentially bringing about a Year Zero.

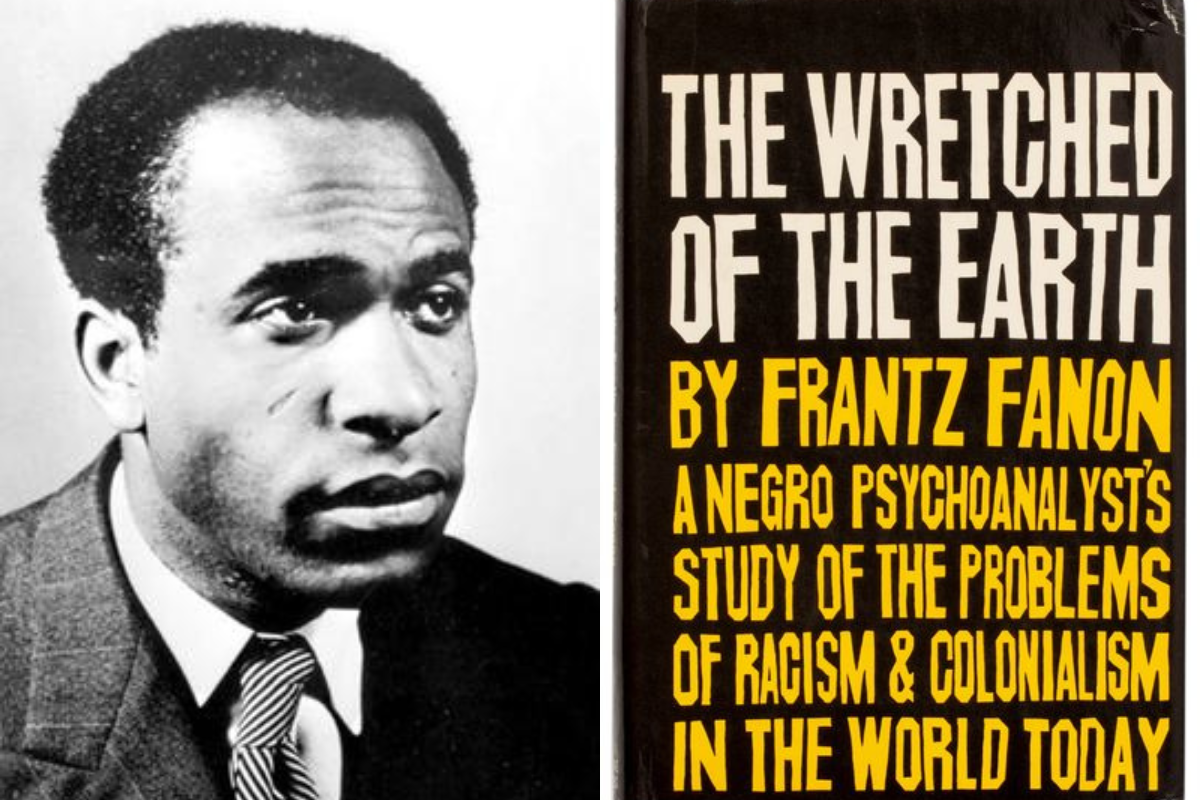

Consider the words of the progenitor of the decolonization movement, Frantz Fanon, in his 1961 book, The Wretched of the Earth. Drawing inspiration from Marxist and Leninist ideologies, Fanon adapts the concepts of class struggle and social justice to the context of racialized colonialism. Decolonization, for Fanon, necessitates political and intellectual upheaval and the complete upending of the social hierarchy. This “is always a violent phenomenon”:

For the last can be the first only after a murderous and decisive confrontation between the two protagonists. This determination to have the last move up to the front, to have them clamber up (too quickly, say some) the famous echelons of an organized society, can only succeed by resorting to every means, including, of course, violence.

Like Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot, Fanon contends that the colonized elite often embrace elements of Western culture and that local intellectuals are prone to adopt the values of the colonizers. These deracinated intellectuals will seek a way for settlers and natives to coexist, yet they are blind to the deeper problems with this: “[the intellectual] does not see, because precisely colonialism and all its modes of thought have seeped into him.” In regions less impacted by the liberation struggle, argues Fanon, colonized local elites may simply replace the foreign settlers while leaving the existing societal structures untouched. In more troubled regions, they may leverage the ensuing political instability for personal gain. It is impossible, Fanon claims, to bring about a fundamental shift in the sociopolitical order without violence.

Even though the Khmer Rouge leaders studied in Paris, there is no evidence that they ever read Fanon. But The Wretched of the Earth, published in 1961, eerily foreshadows the practices they employed a decade later.

Many people blame the rise of the Khmer Rouge on America, and in particular on President Richard Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. As the US–Vietnam War intensified in the late 1960s, Cambodian Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who had initially sought to remain neutral in the conflict, granted the Vietnamese communists access to the port of Kampong Som and allowed them to use eastern Cambodia as a supply route for weapons shipments to North Vietnam. In turn, eastern Cambodia was bombed by the Americans, and, as a result, in March 1970 Prince Sihanouk was ousted by the pro-US politician Lon Nol.

In a bid to return to power, Sihanouk forged an unholy alliance with the Khmer Rouge, a group he had previously sought to suppress. This gave the Khmer Rouge the political capital necessary to swell their ranks from 6,000 to 50,000 fighters, many of whom were peasants loyal to Sihanouk. Following the overthrow of Lon Nol and the Khmer Rouge’s ascent to power in 1975, Sihanouk was briefly allowed to be a puppet head of state before being placed under house arrest.

The extensive American bombardment of Cambodia between 1969 and 1973 fueled intense animosity toward the US and bolstered support for the Khmer Rouge insurgents. Yet, hostility to the US does not fully explain why, once the conflict had ended, the revolutionaries turned on their own people, singling out many groups for eradication, including government officials, Western-educated professionals, landowners, skilled laborers, and Buddhist monks, as well as the Cham and Vietnamese-Khmer ethnic minorities. The Khmer Rouge’s motivations went beyond the defense of Cambodian sovereignty against foreign powers; they were inspired by a broader revolutionary vision that led to a frenzied purge of anything and anyone seen as tainted by the influence of the colonists and invaders.

For scholar Karl D. Jackson, there is a clear connection between the Khmer Rouge and Fanon:

Fanon, like the Khmer Rouge, is anti-proletarian and anti-intellectual as well as being antibourgeois and opposed to nationalist politicians… Just like the Khmer Rouge, Fanon uses geographic location [urban vs. rural] as a most important criterion for identifying class enemies.

In his 1959 doctoral thesis, future Khmer Rouge leader Khieu Samphan contended that Cambodia’s dire economic circumstances stemmed from its exposure to a globalized modern economy. “International integration,” he writes, “is the root cause of the underdevelopment of the Khmer economy.” In his view, the intrusion of the international markets into Cambodia’s essentially pre-capitalist economy during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries diverted development onto a semi-colonial and semi-feudal path. This led to the disintegration of Cambodian “national crafts” like silk and cotton weaving, since cheaper mass-produced foreign goods outsold traditional textiles on the free market. The consequent destruction of Cambodia’s emerging industrial sector compelled unemployed laborers to return to subsistence agriculture. At the same time, modern urban areas populated by civil servants, military personnel, and commercial traders were simply parasitic on the country, argued Samphan—“unproductive investments” that failed to make a meaningful contribution to economic development. The people most to blame, in his opinion, were the middleman bourgeoisie, who sustained their lifestyles by selling agricultural exports produced by peasant labor.

The Khmer Rouge elite also lamented the impact of what they saw as “cultural imperialism.” An official announcement of April 1977 refers to the early years of Cambodian independence, when, after 1954, the country ceased to be part of French Indochina:

In this period, we lost all sense of national soul and identity. We were completely enslaved by the reactionary, corrupt, and hooligan way of thinking, by the laws, customs, traditions, political, economic, cultural, and social ways and lifestyle, and by the clothing and other behavioral patterns of imperialism, colonialism, and the oppressor classes.

The depth of the Khmer Rouge elite’s cultural alienation from the Western-influenced lifestyle of Phnom Penh is obvious in their official account of the city’s capture on 17 April 1975:

Upon entering Phnom Penh and other cities, the brother and sister combatants of the revolutionary army… sons and daughters of our workers and peasants… were taken aback by the overwhelming unspeakable sight of long-haired men and youngsters wearing bizarre clothes making themselves undistinguishable from the fair sex. Our traditional mentality, mores, traditions, literature, and arts and culture and tradition were totally destroyed by US imperialism and its stooges. Social entertaining, the tempo and rhythm of music and so forth were all based on US imperialistic patterns. Our people’s traditionally clean, sound characteristics and essence were completely absent and abandoned, replaced by imperialistic pornographic, shameless, perverted, and fanatic traits.

The aftermath of this social experiment in decolonization known as Year Zero left between 1.5 million and 3 million Cambodians dead from starvation, torture, execution, untreated diseases, forced marches, and forced labor.

Myanmar provides another example of how devastating the kind of radical decolonization described by Fanon can be.

In 1885, British forces took control of what was then Burma and opened its western border with British-controlled India. The colonial administration actively encouraged Indians to migrate to Burma—as they had done in Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and other colonies. This policy sparked considerable inter-communal tension. Indian immigrants assumed diverse roles within Burmese society—from laborers and civil servants to soldiers and moneylenders, some of whom played a pivotal role in local finance. Though some of these immigrants settled in the west of the country, frequently moving back and forth between Burma and India, others made their way to the capital, Rangoon, or took up residence amidst the rice fields of the Burmese delta. By the early 1930s, Rangoon alone was home to 212,000 Indians, both Hindu and Muslim, constituting over half of the city’s population. This demographic change heightened the sense of marginalization among the local Bamar population. As a global recession hit, a significant portion of Burma’s fertile land fell under the control of “non-resident landlords,” mainly of Indian descent. This situation further intensified the perception that foreigners were destroying local livelihoods and eroding the cultural and emotional “essence” of the country.

The growing animus toward the new arrivals soon spread to encompass the country’s Muslim population in general, particularly those who had married local Buddhist women. Since these wives typically converted to Islam and brought up their children in the same faith, these intermarriages were seen as diluting ethnic and religious Burmese bloodlines.

After the British Empire withdrew its colonial presence in 1945, Myanmar was quickly plunged into a maelstrom of ethnic strife. Central to this turmoil was the Bamar perception that Muslims were an unwelcome legacy of colonial rule—or colonizers themselves—and were responsible for a decline in Buddhism's historical prominence in society. In the service of restoring the pre-colonial character of Myanmar, the military began a harrowing campaign of relentless violence and persecution against the Rohingya Muslim community.

As historian Mukul Kesavan has written:

The scale of this ethnic cleansing represents the most extreme triumph of majoritarian politics in South Asia. The persecution of the Rohingya has made Myanmar something of an inspiration to majoritarian parties in neighboring states… Majoritarianism—the claim that a nation’s political destiny should be determined by its religious or ethnic majority—is as old as the nation-state in South Asia; it was decolonization’s original sin.

By January 2018, United Nations reports indicated that almost 690,000 Rohingya Muslims had fled or been forcibly displaced from Rakhine State and found refuge in Bangladesh. Others fled to India, Thailand, Malaysia, and other parts of South and Southeast Asia, marking the largest human exodus in the region since the Vietnam War.

There have been disturbing echoes of the call for radical decolonization in its most violent form in the aftermath of the Hamas attack on Israel on 7 October, which resulted in the tragic deaths of over 1,200 civilians (approximately 200 Hamas fighters were also killed). In response, Najma Sharif, a writer for Soho House Magazine, posted a since-deleted tweet: “What did y’all think decolonization meant? vibes? papers? essays? losers.”

George Washington University’s Students for Justice in Palestine likewise stated,

Decolonization is NOT a metaphor. It is NOT an abstract academic theory to be discussed and debated in classrooms and papers. It is a tangible, material event in which the colonized rise up against the colonizer and reclaim control over their own lives.

Similar sentiments were expressed at some of the top universities in the US.

Within Western academic circles, there is a prevalent worldview that frames Israel as a society of settler-colonialists who have usurped the lands of the indigenous inhabitants. Some of the same people who considered the question “Where are you really from?” to be a microaggression when directed at a non-white person are ready to label all Israelis as “colonists,” implying that their presence in the region is illegitimate. The chant “from the river to the sea” is also frequently understood to advocate the decolonization of Palestine through the complete obliteration of the state of Israel.

So, how has an ideological perspective that inspired the atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge gained so much traction within Western academic institutions?

At the core of this phenomenon is a worldview that categorizes people in binary terms: as oppressor and oppressed. According to this perspective, those identified as oppressors are considered white or “white-adjacent,” privileged individuals who exploit the less privileged both economically under capitalism and by colonizing their lands. It is easy to see how Israelis in particular and Jews in general can be viewed through this prism.

In many parts of the media and academia, this perspective has eclipsed traditional universal humanist values, such as respect for all human life. Yet, when this simplistic analysis grapples with the intricate realities of the Middle East, it cannot map these complexities onto an American racial grid. Stubborn facts like the existence of a substantial community of Ethiopian Jews, alongside approximately five million Mizrahi—descendants of Jews from Iran and the Arab nations—contradict the notion that most Israelis are “white.” These people are not settlers or colonialists. They are refugees, expelled from their original homes in places like Baghdad, Cairo, and Beirut after centuries of coexistence with the Muslim populations there.

The kneejerk hostility the decolonization proponents harbor toward Israelis is indicative of their broader attitudes toward Western democracies as a whole. According to them, Western countries are colonizing nations and imperialists, while foreign autocracies and sectarian extremists like Hamas are perceived as opponents of imperialism and thus deemed to be freedom fighters and even forces for good.

Western proponents of decolonization tend to romanticize groups like Hamas and the Khmer Rouge, whom they view as literally fighting a battle that, for the Westerners, is merely symbolic. The West itself will never be decolonized. The idea of exiling the descendants of white Europeans and giving the US, Canada, or Australia back to their original inhabitants is politically and logistically impracticable to the point of absurdity. Instead, these Westerners find solace in the Year Zero fantasy they believe to be unfolding in the Middle East, in which they hope to witness what they see as the rightful occupants reclaiming their land. “No peace on stolen land,” they chant. The lands where they themselves live will never be returned—no matter how many land acknowledgements they make. But they can assuage their guilt by championing the cause of those they see as the natives, the “rightful occupants” of non-Western countries, in their struggles against the heinous recent “invaders.” They are spectators of a dangerous game, in which someone else will always pay a bitter price.