Canada

In Canada, ‘Decolonization’ Has Become a Profitable Enterprise

British Columbia’s nursing regulator paid consultants almost $100,000 to design a special complaints process for Indigenous patients.

As regular readers of Quillette will know, many Canadian institutions have fervently adopted the cause of “decolonization”—a vaguely defined term that one university describes as the dismantling of “assumed Euro-western disciplinary constructs and traditions.” This can mean anything from abolishing musical scales (which “perpetuate and solidify the hegemony of [the] Euro-American repertoire“); to reimagining our scientific understanding of sunlight, so as to correct “the reproduction of colonialism” that has infected “physics and higher physics education”; to assailing the gender binary through a “decolonizing act of resistance.”

That’s the theory, anyway. In practice, institutional efforts at “decolonization” generally translate into affirmative-action hiring programs and policies to mandate symbolic (generally empty) gestures such as land acknowledgements. They’ve also created a cash cow for “specialist” administrators and third-party consultants in what is now known as the “equity, diversity, inclusion, and decolonization” sector. The premise is that decolonization is so difficult and complex that it can only be overseen by said (highly paid) professionals.

My own professional sector, nursing, provides a useful case study. In British Columbia, where I live and work, nurses are licenced by the British Columbia College of Nurses & Midwives (BCCNM), whose offices are located “on unceded Coast Salish territory, represented today by the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations.” In other words, Vancouver.

If a patient feels that he or she has experienced “incompetent, unethical, or impaired nursing or midwifery practice,” he or she can complain to the BCCNM through its complaints portal. It’s not a complicated process. You send an email describing what the nurse allegedly did, when the incident occurred, and whether there were any witnesses. If you’ve already complained to someone else, you’re supposed to note that as well, along with your suggestions for resolving the complaint. That’s it.

But apparently, this process is just too onerous—and even dangerous—for Indigenous people. And so the BCCNM has paid C$97,000 to a self-described “boutique business process management firm” called Novatone, which has duly produced a lengthy report on how to “make the BCCNM complaints process safer for Indigenous Peoples.” The same title—mantra might be a better word—appears at the top of all 50 pages: Looking Back to Look Forward: How Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and doing must inform the BCCNM feedback process and reflect the principles of cultural safety, cultural humility, and anti-racism.

(For the benefit of those outside Canada, the mystical-sounding phrase, “ways of knowing,” along with its “being” and “doing” variants, has now entered the official idiom as a means to signify the unfalsifiable shaman-like intuitions that supposedly guide the consciousness of Indigenous people throughout every facet of their existence—including, apparently, complaining about the care they receive from nurses.)

Everyone deserves to be served respectfully by medical professionals. And it is true that Canada has witnessed tales of Indigenous people being treated abominably by nurses. But the composition of complaints made to the BCCNM does not suggest that the abuse of Indigenous patients is a systemic problem in BC. In fact, Novatone’s own analysis of 887 Indigenous complaints, as detailed by the BCCNM’s Inquiry, Discipline, and Monitoring team, shows that only two percent could be described as “possibly” related to Indigenous-specific racism.

Oddly, in fact, Novatone’s main concern seems to be that not enough Indigenous people are choosing to “engage with the current complaints process.” The reason why there is so little evidence of racism to be found, the consultants conclude, is that “Indigenous Peoples” must find the above-described email process to be “complicated, confusing, and inaccessible.”

Too many complaints? That’s racism. Too few complaints? Well, that’s racism, too. Make it make sense.

Much of Novatone’s report consists of boilerplate summaries of the United Nations Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples and the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action—lengthy swathes of text that read like a ChatGPT response to the question, Why is absolutely everything racist? Various consciousness-raising passages urge nurses to escape their Eurocentrism through the channeling of a “one heart one mind” philosophy, “Two Eyed Seeing,” and “an anti-racist ethos that honours individual truths and stories.” (I have no idea what these concepts mean, and I suspect the authors don’t either.) For good measure, Novatone also threw in a lengthy international literature review, extolling, for instance, “the interconnectedness, cohesion, community, and accountability [of] Māori law, [which] invites a collective practice of restoration into their communities while adhering to traditional principles of justice.”

I’ve been a BC nurse for over a decade. The only examples of overt racism I’ve witnessed in that time are similar to the condescending claims contained in the Novatone report—i.e., Indigenous people being depicted as noble savages, or even infants, who are incapable of negotiating simple institutional protocols unless the entire process is redesigned in a way that (supposedly) aligns with their ancient “ways of knowing.”

Over the course of my nursing career, I’ve seen the focus of professional development and institutional policy-making shift—gradually, at first, then rapidly in the past four years—from regulating and improving skills and competencies, to monitoring our pronoun usage, obsessing over “safe spaces,” and lecturing us about our supposed white supremacy. We are now told to accept that white people working within BC’s health system are suffused with subconscious racism. And to deny one’s “subconscious racism” is, apparently, to declare oneself both a heretic and an overt, capital-R Racist. The BCCNM has claimed that the entire Canadian healthcare system was “designed to eradicate Indigenous Peoples.” Readers will be gratified to learn that I have never tried to eradicate a single Indigenous person, nor seen any of my colleagues do so.

It’s no secret that the BC nurses being endlessly hectored about diversity, equity, inclusion, and decolonization are already overworked and burnt out. To see our regulator spend almost $100,000 on another ideologically driven initiative purporting to identify its members’ inadequate commitment to anti-racism confirms just how detached healthcare regulators are from front-line nurses—the nurses who do the actual caring.

I do not believe that it is too complicated or confusing for an Indigenous person to send an email complaint to the BCCNM, whether by themselves or with the assistance of a trusted friend or family member. White people can do it. So can people who aren’t white, and who may even be new immigrants who don’t or barely speak English. It happens all the time. And it’s bizarre—I’d go so far as to suggest, racist—to insist that only Indigenous people lack basic 21st-century communications skills.

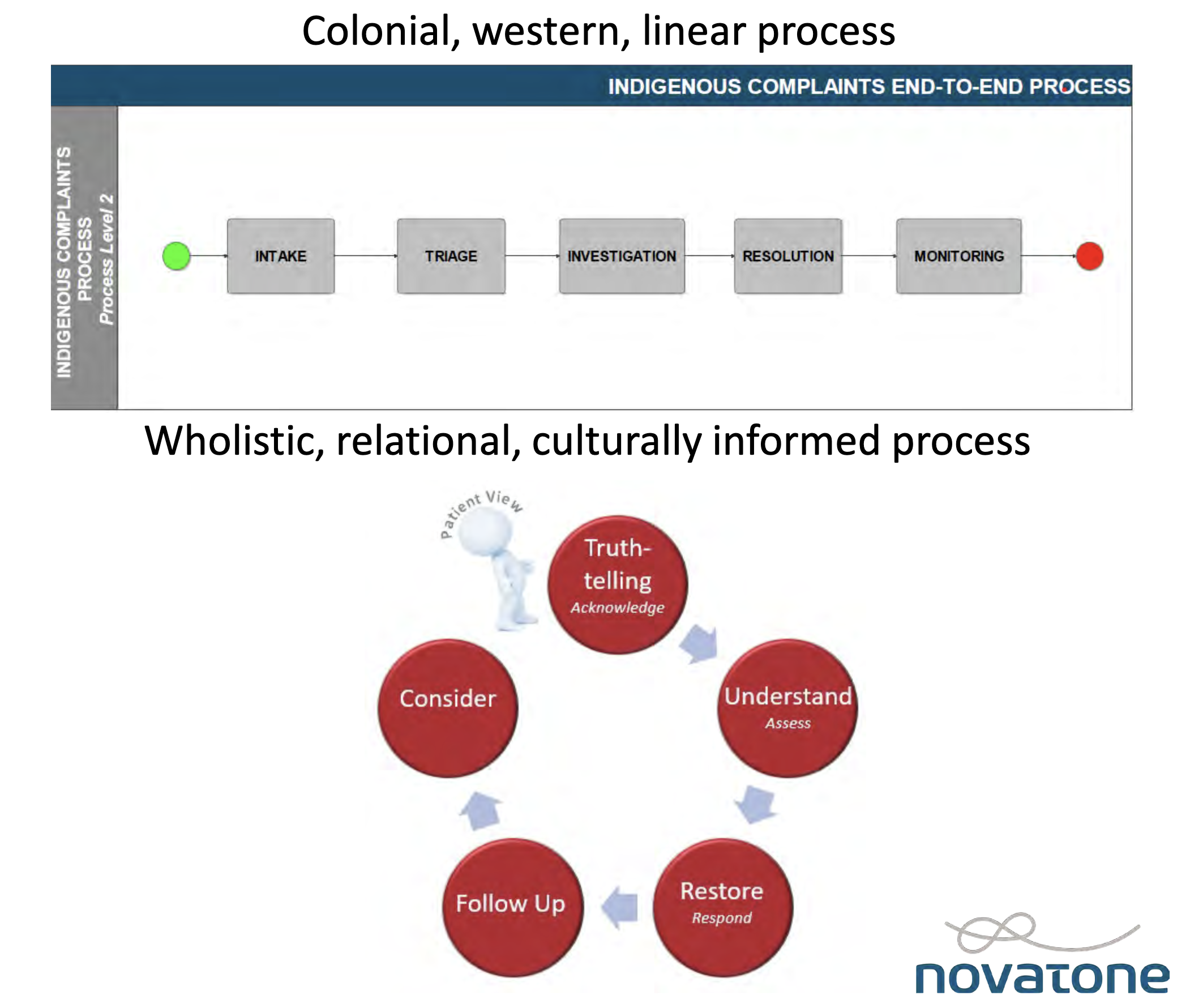

Novatone’s proposed solution to spare Indigenous people exposure to BCCNM’s current “colonial, western, linear” complaints process is a separate process for Indigenous persons—yes, that’s right; “separate but equal,” as the expression goes. This will consist of a “feedback journey” that includes a “truth-telling form.” Rather than having Indigenous people submit a complaint in their own words, a BCCNM official will fill out the “truth telling” form on their behalf, much as one might do for a small child, or an illiterate person. How progressive.

What isn’t clear is how Indigenous complainants will connect with the BCCNM to “tell their truth” in the first place: While Novatone has explained at great length how it is too confusing for Indigenous people to send an email to [email protected], there’s no proposed alternative for launching a “feedback journey” en route to the promised “restoration” at the end of the new process.

Presumably, the “journey” will be launched in much the same way as it is now—which is to say, by email. Except, this time, there will probably be a special Indigenous email address, such as [email protected]. If so, I eagerly await the BCCNM’s self-congratulatory announcement of this bold decolonization-industry innovation.

Racism has no place in healthcare. And I support organizational policies that punish or remove staff who engage in racist or otherwise discriminatory conduct. I would be happy to see my annual BCCNM license fees go toward investigating and disciplining nurses who commit such real abuses. What I can’t support is paying a consulting firm more than the average nurse’s annual salary to write what is, in effect, a padded out undergraduate paper laced with faddish social-justice jargon. Not a word of it will help the Indigenous people who are the professed beneficiaries of the exercise. What a waste.