A review of Napoleon Symphony: A Novel in Four Movements by Anthony Burgess, 416 pages, W.W. Norton (October 2014).

Napoleon Bonaparte died in 1821, but it has taken until 2023 for Hollywood to produce a definitive biopic of the man who came closer than anyone else to conquering the European continent. One could argue that the story was just waiting for the right director; that Ridley Scott is to cinema what Bonaparte is to world history. But what most people don’t know is that Napoleon could have been released fifty years earlier, with an arguably even bigger name attached to it than Scott’s, had things turned out differently.

Deterred by financial burdens and the poor performance of Waterloo (1970) at the box office, Stanley Kubrick never managed to get his blockbuster about the life and death of Napoleon Bonaparte past the planning stages. But that does not mean it left nothing to show for itself. Off the back of the success of A Clockwork Orange—a stupendously successful adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s book of the same name—Kubrick enlisted Burgess’s help to mould the life of le petit caporal into a cohesive narrative. Burgess would write the Great Napoleonic Novel, and the producers would transubstantiate the raw prose into a serviceable screenplay. Although the film eventually fell through, the novel was completed and published in 1974.

As much a musician as a writer, Burgess intended the novel as a counterpart not only to Kubrick’s movie, but also to Beethoven’s Third Symphony, “which began by being about Napoleon and ended by being about any great military hero.” His vision for the book was “the filling out of the theme which had inspired the symphony,” or, as he more poetically puts it in the book itself:

Somehow to give

Symphonic shape to verbal narrative,

Impose on life, though nerves scream and resist,

The abstract patterns of the symphonist.

Burgess was a failed composer, and he had a profound knowledge of music that is evident throughout his œuvre. Indeed the “abstract patterns” of Napoleon Symphony echo the framework of Burgess’s earlier novel The Worm and the Ring, an adaptation of Wagner’s Ring Cycle set in an English grammar school. The decision to use Symphony No.3 for inspiration this time around was not random. The piece was originally dedicated to Napoleon, although Beethoven later renamed the Bonaparte Symphony the Eroica, after learning that Napoleon had styled himself Emperor: “Now he will think himself superior to all men, become a tyrant!”

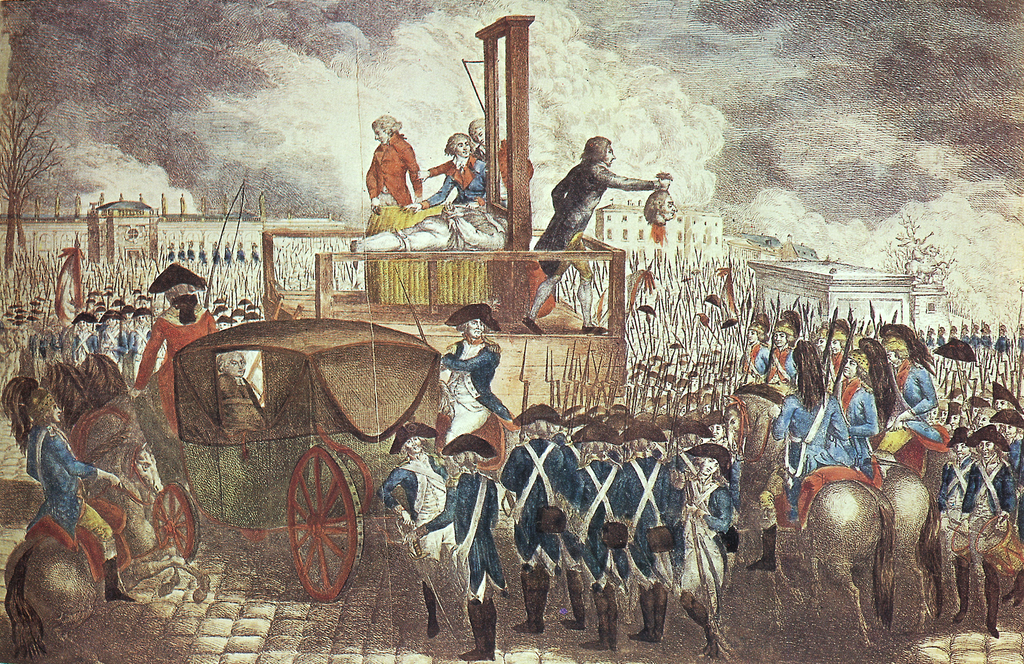

Eroica, née Bonaparte, is a symphony in four movements. Thus, the novel’s four acts: the Italian and Egyptian campaigns; Napoleon’s coronation in Paris; the Russian campaign; and his exile on St Helena after the defeat at Waterloo (which is itself conspicuously absent from the book). The novel’s style also attempts to echo the complexity of Beethoven’s orchestral tour de force, which makes for difficult reading. Burgess expects readers to slog through vast expanses of turgid prose, punctuated here and there by random outbursts of verse, nonsense songs, and occasional dream sequences. Mirroring the decline of Napoleon’s mental faculties, the prose becomes progressively more febrile, until every third word seems to be capitalised, italicised, prolonged, truncated, or simply made up. In the fourth act, the Corsican’s thoughts are more a mudslide than a typical stream of consciousness:

Bastille tuiler massac swiss guaaaaaaar sept massac…Nat conven proclam 1st rpblc louis 16 reign terror marie antoin 9 thermidooooooor…Marriage jsphn jsphn jsphn general buon bon campaign italy love…Alexander alxndr lxndr xnd x war austr fren occup vien 2nd time annex papal states pius vii excommun pius vii arrested.

It is a shame Napoleon Symphony never became an audiobook, as the novel strives at every turn for a particularly aural quality. The book contains far more dialogue than description—as we might expect in a novel that doubled as a script—and even the descriptions are rich in a kind of Joycean wordplay that betrays a delight in the silliness of how things sound. Napoleon spends his time in exile musing on the etymological connections between the English “spade” and the Italian “spada.” Entire paragraphs are rendered in French, Italian, and Latin, while the omniscient, omniglot narrator has no qualms smuggling unwieldy German loanwords like “Guglhupf” and “Topfenpalatschinken” into otherwise austere passages, where they loom like guests wearing Lederhosen at a black-tie dinner. Nor can Burgess ever resist a good pun: for instance, his characters speak of “the fundaments of army law” and nickname a certain Admiral Tshitshagov “Shit Shag Off.” And Burgess’s determination to compare everything to music soon becomes tiring. Who else would liken Bonaparte’s eyes to “a whole Haydn orchestra”, or describe an act of sexual intercourse as lasting “rather less time than sixteen bars of an aria in moderate tempo”? (The Bad Sex in Fiction award would not be introduced for another twenty years.)

Napoleon Symphony probably wouldn’t be published nowadays. Besides its frustrating opacity, it revels in lascivious episodes and brutal acts of violence, all rendered in close, lecherous detail. The descriptions of the Russian campaign are especially vivid. Hunger compels the soldiers to turn their horses into soup, while as freezing weather gnaws away at the French forces, the dead soon outnumber the living: “Hundreds of yelling bodies piling up… you could see the blood pouring out and freezing at the same time, boots crunching into skulls and eyes popping out.” Burgess writes:

As soon as the mob saw the flames licking they were all seized with a great fucking panic and they began to run to both bridges and then to run over, pushing and clawing (those that had any claws left), screaming and cursing us for the flames, then a great number went over screaming, all outlined in fire… The river was no longer ice and water but people, dead and dying, absolutely fucking blocked.

In Burgess’s version of events, Napoleon ultimately returns to Paris to clear his name amidst a maelstron of defamatory rumours. In an invented episode in which the man who believes himself to be “greater than Charlemagne” makes his way about Paris in disguise, evesdropping on the conversations of his soldiers, he hears nothing but slander and sedition. When he is recognised at a café, he is rewarded with “a small cup of diarrhée noire.”

Burgess also ridicules Napoleon’s supporting cast and the revolutionary agenda in general. Talleyrand is an ass, Berthier a bumbling, stuttering oaf. Germaine de Staël is most notable for her “outsized clitoris.” Burgess’s criticisms of the ravenous ambition and utopian naïveté that propelled Napoleon on his quest to conquer Europe are scathing. In his version of events, the death of God and the birth of the Napoleonic era are rolled up into a kind of irreligious ritual: “Heaven had been cancelled by some act of the Year One. God had been put to sleep like an old dog. No history, no vindication.”

It’s easy to pick on the dead, and easier still to rubbish moth-eaten ideologies that linger on long after their use-by date. A staunch monarchist, Burgess would have baulked at the rise of republican sentiment in his own country were he alive today, and despised the broader reshaping of Western society along secular lines. Like Edmund Burke, who lambasted the revolutionaries’ division of France into “square measurements” that could inspire no “sense of pride, partiality, or real affection,” Burgess was content to live in an imperfect world; he believed that the rational always came at the expense of the cultural, and took issue with any attempt to simplify the machinery of civilisation, whether it was the calendar or the cash in one’s pocket. In 1971, only a few years before the publication of Napoleon Symphony, the British government decimalised the pound sterling. “Before the shameful liquidation of the British penny into a p,” Burgess would later reflect,

there had been an eminently rational coinage, with twelve pence to the shilling and twenty shillings to the pound… By brutal government fiat… this beautiful and venerable monetary complex was abolished in favour of a demented abstraction that was a remnant of the French revolutionary nightmare.

The protagonist of Napoleon Symphony often seems to be little more than a punching bag on which Burgess can take out his grievances about the dullness of modernity and the brutalities of the Revolution. But the novel, for all its faults, is more nuanced than that. Burgess’s Napoleon is more tender-hearted than the primary sources suggest, equally capable of developing friendships with Milanese priests and the daughters of English governors. He is also a bulwark against other dangerous ideological currents. In one passage that prefigures the rise of Nazism, for instance, a German prisoner waxes lyrical about the destiny of the Germanic people. Napoleon responds that “It’s a sin to want to die for a nation. What I want is a united Europe, not a bundle of yapping and farting little nations.”

Ironically, Napoleon was to get his wish for a united Europe, as the “Epistle to the Reader” with which the novel ends points out:

This, then, is what the novel is about:

Its key E-flat, its form pseudo-symphonic,

Ending upon a forte major tonic,

Napoleon triumphant—so he is,

Since, unfulfilled in life, that plan of his

Now operates at last: proud England, cowed

Back into Europe, bumbled, silenced, bowed.

Let hell’s or heaven’s belfries clang out loud.

Burgess is referring to Britain’s entry to the European Economic Community in 1973. He did not foresee that, less than fifty years later, Britain would have left again. Perhaps recent events have warranted another go at the Napoleon story. But whether Ridley Scott’s Napoleon will be bold or moralising or anachronistic enough to make such a connection remains to be seen. Personally, I’ll settle for finally getting to see Waterloo.