enlightenment

Anti-Enlightenment Thinking, Past and Present

The Enlightenment was as remarkable as it was unexpected, but it led directly to the benefits we enjoy today.

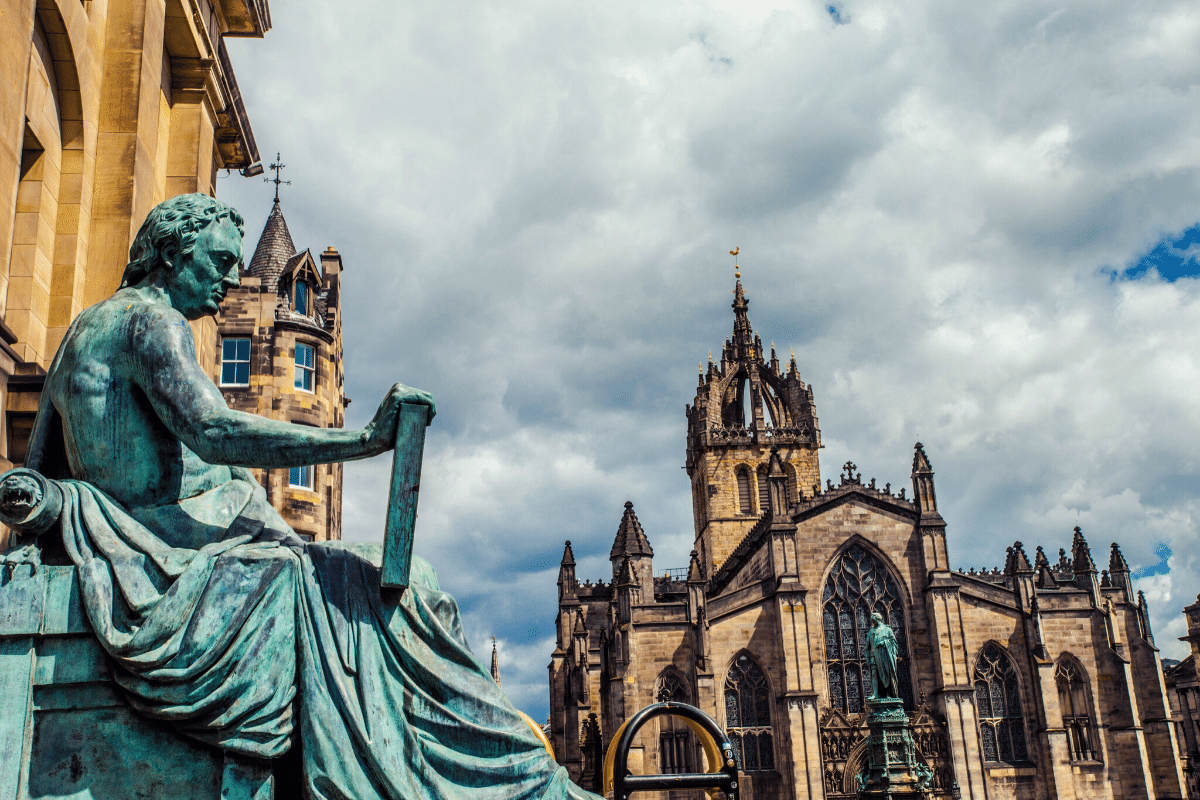

On the morning of 27 October 1553, as the bells of St. Pierre Cathedral began to strike eleven, the constabulary of Geneva led a bound man out of the city’s south-east gates. The prisoner was a Spaniard called Miguel Serveto. We know him today as Michael Servetus. He was immensely learned—a polyglot, scholar, theologian, scientist, and Renaissance man in every sense of the word. While studying medicine in Paris, he had written the first book in Europe to give an accurate description of how the blood circulates between the heart and the lungs (Middle Eastern scholar Ibn al-Nafis had previously written one in Arabic).

Servetus was best known, however, as a heretic. This might seem odd, for Servetus was a devout Christian, who professed Christ as his saviour. But after reading the Bible and the works of the Church fathers, Servetus concluded that there was no basis for the concept of the Holy Trinity—one God in three persons: the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Jesus was undoubtedly the son of God, he concluded, but Jesus did not exist until God created him in Mary’s womb. Christians described Jesus as the “eternal son of God” when, in fact, they should call him “son of eternal God.” The placement of the word “eternal” would prove a matter of life and death.

Anti-Trinitarianism was not Servetus’s only heresy: he also opposed infant baptism, arguing that people should only be baptised if they decided to join the Church of their own volition. But it was his refusal to call Jesus the “eternal son of God” which proved his undoing.

Servetus was a very intelligent man, but also a fiery and intemperate one. In his writings, he called infant baptism “a diabolical invention and infernal falsehood destructive of Christianity” and described the Holy Trinity as a three-headed monster. He was expelled from France for these views. On 24 October, he was arrested in Geneva. That same day, the city council found him guilty of heresy and pronounced the sentence dreaded throughout Medieval Europe:

We condemn thee, Michael Servetus, to be bound, and led to the place of Champel, there to be fastened to a stake and burnt alive, together with thy book, as well the one written by thy hand as the printed one, even till thy body be reduced to ashes; and thus shalt thou finish thy days to furnish an example to others who might wish to commit the like.

Servetus would not change his opinion. He spent the morning of his execution debating Protestant theologian, William Farel, who urged him to repent and save his soul. Servetus asked Farel to produce a Bible verse that described Jesus as the son of God before his incarnation. Farel could not satisfy him. The exchange was interrupted by the arrival of Geneva’s de facto religious leader, Protestant reformer John Calvin himself.

Calvin and Servetus had once been friends, before they fell out over the question of the Trinity. The two men were alike in many ways, from the depth of their erudition to the steadfastness of their views. Servetus had been arrested at a sermon that Calvin was preaching, and Calvin had been the driving force behind his prosecution.

Since Calvin’s own followers were being sent to the flames throughout Catholic Europe, Calvin had good reason to sympathise with Servetus. But he failed to make the connection, as he thought of his followers not as heretics but as martyrs to the truth. In addition, his position in Geneva was far from secure; the city was riven with theological strife between Calvin’s followers and those of a rival Protestant sect. Calvin needed to show that he could be just as tough on heresy as the Catholic Church that he sought to overthrow. And this wasn’t difficult, since he believed wholeheartedly that heresy deserved death. “Whoever shall now contend that it is unjust to put heretics and blasphemers to death will knowingly and willingly incur their very guilt,” he writes in his own tract on heresy. Throughout the trial, he prayed Servetus would repent, and when he did not, asked the council to grant his old friend a faster death by beheading, as a final mercy. But he did not doubt either the justice or necessity of putting Servetus to death.

At their final meeting, Calvin insisted that he had never born any personal animosity against Servetus:

Sixteen years ago I spared no pains at Paris to gain you to our Lord. You then shunned the light. I did not cease to exhort you by letters, but all in vain. You have heaped upon me I know not how much fury rather than anger. But as to the rest, I pass by what concerns myself. Think rather of crying for mercy to God whom you have blasphemed.

Servetus remained quiet and humble, but he would not repent. In obedience to St Paul’s exhortation to shun heretics (Titus 3:10–11), Calvin left the room. The kindly Farel stayed with Servetus to the end, walking beside him on the fateful road to Champel. Servetus asked God to forgive both his sins and his accusers and professed his belief in Christ as his saviour. But he would not repent.

Today, Champel is a leafy suburb of Geneva offering fine views of the rocky Salève massif to the south. The University Hospital now stands opposite the spot where Servetus was executed. A nearby street bears his name.

On that fateful October day, the Lord Lieutenant of the city and his herald were waiting on horseback amidst the drifts of fallen autumn leaves, beside the executioner and the stake, which was surrounded by bundles of wood. Servetus saw that the wood was still green and knew that his death would not be fast. A small procession of spectators gathered round. Farel called on them to pray for Servetus; Servetus remained silent.

The first person in Europe to write an accurate account of pulmonary circulation was then led to his pyre. The executioner secured Servetus to the stake with an iron chain, placed a copy of his heretical book Cristianismi Restitutio in his arms, and bound book, man, and stake together with a rope. He placed a crown of leaves covered with sulphur on his head and bought forth the burning torch. “Misericordias!” Servetus cried.

Green wood burns slowly. Some of the spectators—either out of impatience or compassion—threw bundles of dry firewood onto the pyre to hasten Servetus’s end. As the flames began to take hold of him, the air filled first with smoke and then with the stench of burning flesh. The ordeal continued for minutes. Finally, Servetus gave a last cry of “Jesus Christ, thou Son of the eternal God, have mercy upon me!” Son of the eternal God, not eternal Son of God—Servetus held to his beliefs to the end. He spoke no more, and the fire consumed his body.

Servetus’s fate was unexceptional in the Europe of that time. But not everyone approved. One of Calvin’s critics, Sebastian Castellio, writes in his book Contra Libelum Calvinim (“Against Calvin’s Booklet”):

To kill a man is not to defend a doctrine: it is to kill a man. If Calvin had killed Servetus for saying what he believed to be true, then Calvin killed him for telling the truth. He should have been taught, not killed, if he was wrong. I believe that on judgment day God will judge morals, not dogmas.

It was, perhaps, a sign of things to come.

I first wrote Servetus’s story in 2019, as the prologue to a book defending the Enlightenment. As I wrote, I frequently found myself wondering if there was any point to this enterprise. Enlightenment values had prevailed throughout the Western world, after all, and would never again be challenged. Defending the Enlightenment seemed unnecessary.

I don’t have those doubts anymore.

In 2020–21, the world was thrown into chaos by the global COVID-19 pandemic, which eventually claimed between 7 and 32 million lives. But thanks to modern science and industry—products of the Enlightenment—we were able to rapidly develop, mass produce, and roll out vaccines, which prevented an estimated 19.8 million deaths, reducing the worldwide mortality toll by around 63 percent.

Yet throughout this, many thousands of people around the world committed acts of collective self-harm. They packed themselves together indoors, creating superspreader events. They rejected centuries of modern science dating back to Servetus’s studies of human circulation in favour of quack treatments ranging from silver-infused toothpaste to household bleach. Some spread bizarre conspiracy theories through social media; some even denied that the virus exists.

COVID-19 has not been our only challenge. On 16 October 2020, Samuel Paty was beheaded by an Islamic extremist outside a suburban Paris school after he showed a caricature of the Prophet Mohammed in class during a lesson on freedom of speech. Fourteen people were charged with complicity in the murder. This was not the psychotic act of a lone madman, but a premeditated crime carried out by people who shared John Calvin’s belief that those who fail to show due deference to their religious beliefs should be killed. Four centuries ago, this attitude would have been unexceptional in much of the world, including France. Hundreds of millions of people in non-western countries are still sympathetic to that view. Blasphemy remains a capital crime in Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Brunei, Mauritania, and Saudi Arabia.

According to NASA, 2020 was also the joint hottest year on record. The world is warming at a rate unprecedented in historical times; much of this warming is driven by the burning of fossil fuels; and these changes are causing disruptions to our agriculture and water supply, as well as more frequent and severe heatwaves, fires, and storms. A good understanding of science will be critical if we are to manage these risks and reverse the trend. Yet, as in the debate over our collective response to COVID-19, many of the loudest voices on this subject are also the least informed. In the wake of devastating bushfires in Australia in the summer of 2019–20, the internet was filled with false or exaggerated claims that the fires were caused by arson.

There were more troubles to come: the Chinese government’s brutal crackdown on peaceful pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong in June 2020; the storming of the US Capitol in January 2021; Vladimir Putin’s indefensible invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 in a bid to resuscitate the supposed glories of a pre-Enlightenment imperial Russia, cheered on by a wacky coalition of the far left and far right.

And then, on 7 October, we witnessed an almost unimaginably horrific terrorist attack on Israeli civilians, which has been greeted with denialism and even celebration—not only from Islamists, but from sections of the Western hard left, some of whom have gone beyond valid criticism of Israel and concern for the Palestinians to excuse barbarism and savagery. The attack of 7 October was as pointless as it was obscene, showing the same level of intolerance and brutality as the burning of Servetus.

All this suggests a failure to appreciate just how much we’ve gained from science, the rule of law, the recognition of human rights, and the rest of the legacy of the Enlightenment.

“What is Enlightenment?” asked Immanuel Kant in 1784. It is the desire to take responsibility for our own welfare and—rather than praying for divine intervention or hoping for a better world in the afterlife—make concrete improvements to our lives in the here and now. It means liberation from the brutal constraints of the world we were born into and from the worst excesses of our own nature. As a historical movement, the Enlightenment was as remarkable as it was unexpected, but it led directly to the benefits we enjoy today, including the right to publish articles like this one without fear of being sent to the flames for heresy. This right must be defended.

Parts of this article have been adapted from the book Why the Enlightenment Matters: The Shift in Our Thinking that Made the Modern World by Adam Wakeling, 415 pages, Australian Scholarly Publishing (May 2023).