Politics

The Immigration Conundrum

Migration from the developing world to the West will continue until and unless international development can improve the societies people are leaving.

Immigration from poor countries has a perverse effect on the rich. Instead of working out, through observation and experience, how to address the poverty and violence which convulses so many developing nations, the preferred response is a mixture of moral posturing and ignorant prejudice. Sir Paul Collier, an Oxford professor, stands out for his clear thinking on this and for his unwearying advocacy of change. His work, and his pleas for a reform of how we confront this increasingly perilous matter, ought to be better attended.

In 2015, Angela Merkel, then Chancellor of Germany, decided—without consultation—to open Germany to migrants. Around a million came, mainly from Syria: a huge, rapid shift in a country where immigration had been moderate. The largest German minority had been Turks, attracted to work in Germany’s large manufacturing sector, and in most cases, they had been in the country for decades. Merkel was applauded by liberals everywhere for her generosity of spirit, yet her gesture was, more quietly but at times venomously, resented by her neighbours, who believed she had left them to cope with the consequences of a policy that had made Europe an even greater attraction to immigrants than before.

Inside Germany, the legacy of Merkel’s decision became clearer, albeit with a time lag. In the latest Politico poll, the far-right party, the Alernativ für Deutschland (AfD), is now running ahead of the ruling Social Democrats, second only to the centre-right coalition, the CDU/CSU. The AfD’s success has grown in a few years from a gathering of conservative economists to one of the most successful populist parties in Europe, and it now drives wedges within the centre right. Friedrich Merz, the CDU leader, broke the strict cordon sanitaire between the AfD and the centrist and left-wing parties when he countenanced the possibility of collaboration with the upstart group at regional and local levels, especially in the east of Germany, where it is the dominant force.

In 2015, the conservative government in Sweden followed Merkel’s lead and opened its doors to all who wished to enter: then Prime Minister, Fredrik Reinfeldt, asked Swedes to “open their hearts” to the record pace of immigration, arguing that refugees “come into Swedish Society to build it together with us.” Many did “open their hearts”; many more saw the immigrants as overwhelming their famed welfare system. As the Brookings Institute has pointed out, the nearly 166,000 people who rapidly migrated to Sweden were equivalent to five million immigrants abruptly settling in the US (which received only 83,000 applications for immigration that year).

The result has been similar to that seen in Germany. The Sweden Democrats (SD), the far-right party founded in 1988, soon became the most powerful force on the country’s right wing, and was largely responsible for the right coalition’s victory in the polls last year. The new government, under the strong influence of the SD, has quickly moved to radically restrict immigration—a move which will see Sweden take a dim view of the new European Union migration pact, which is about to be debated.

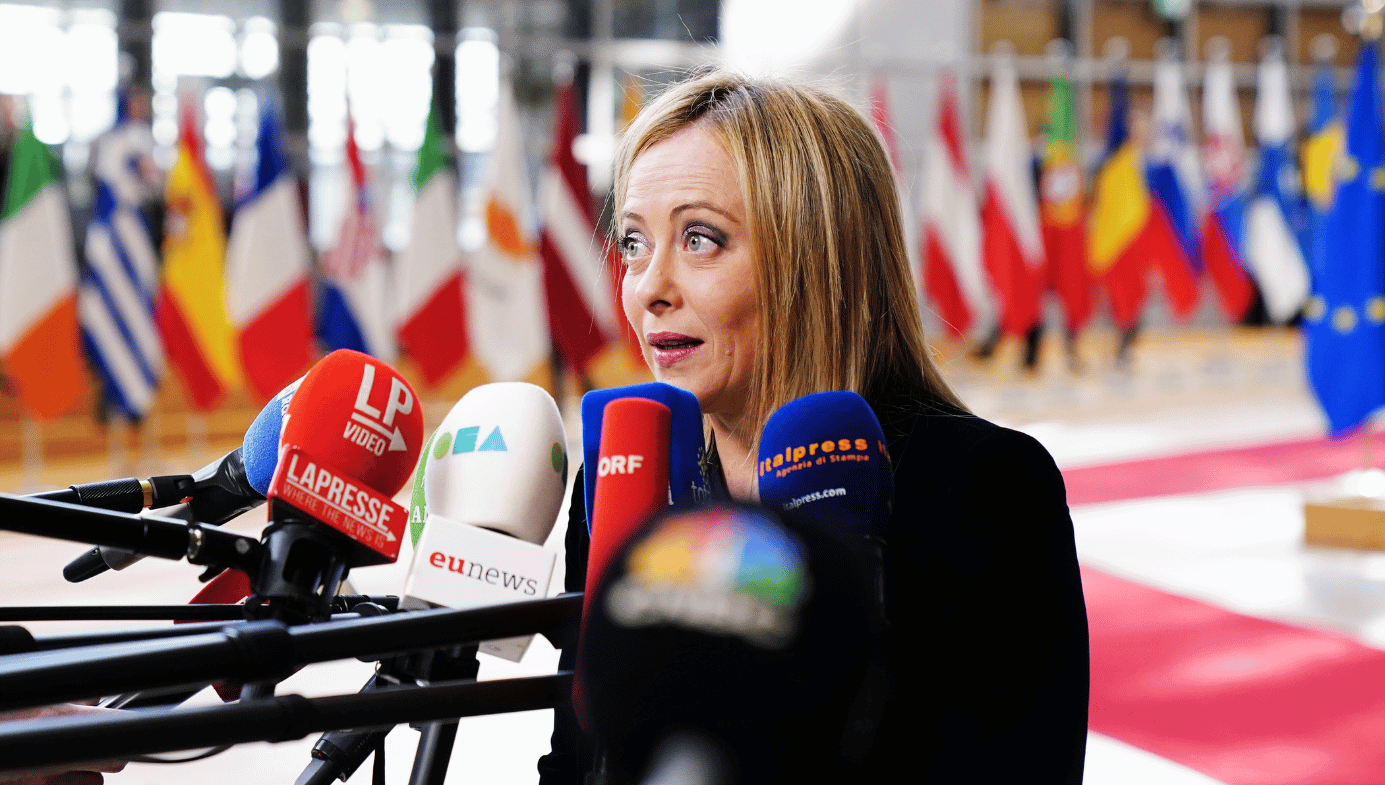

This trend reproduces itself almost everywhere: the Italian government is led by the far-right Fratelli d’Italia, which produced Italy’s first female Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni. It is noted for proposing harsh solutions to the surge of immigrants in a country whose position in the Mediterranean makes it the target of growing waves of migrants. In France, Marine le Pen, whose Rassemblement National takes the hardest line of any major party on immigrants and on the threat of Islamism, is presently on track to be the next president of the country. In the UK, the ruling but unpopular Conservative Party finds itself beset by protests. The numbers crossing the English Channel in small boats grew to over 45,000 last year in defiance of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s assurance that they would be halted (there is likely to be a small decline this year).

Mass migration empowers a new right everywhere. Only in Spain, where the far-right Vox saw a sharp fall in popularity in a snap general election, has the trend been challenged. For politicians of the right and left elsewhere, the conclusion remains stark: talk tough, and try to act tough, on flows of migrants. Though this stance has conventionally been the recourse of the Right, there is now little dividing it from the Left on this topic. In Denmark, the ruling Social Democrats have one of the most restrictive policies in Europe. In the UK, Sir Keir Starmer, the leader of the opposition Labour Party, commands a large lead in the opinion polls, travelling to France to seek an agreement with French President Emmanuel Macron that will treat people-smugglers as “terrorists.”

Democratically elected leaders must respond to the demands of their electorate; it is wholly legitimate to demand control of national borders. But to leave it there, and to compete in displays of adamant hostility to the influx of often desperate men and women born on the wrong side of the rich/poor chasm, has been shown not just to be tasteless, but also useless. The more Donald Trump railed at “rapists and criminals” entering the US, the greater the number of families who tried to elude the US border guards, and still do. For all of Prime Minister Meloni’s hard line on migrants, prompting public rows with France last year and Germany this month, they stream into Italy, recently causing fights with the Italian police and the collapse of facilities on the Sicilian island of Lampedusa.

Collier has been the most authoritative public voice insisting on the possibility of a third way. In an interview with Social Europe, he argued that politicians in the rich world must combine two approaches: compassion and solidarity combined with enlightened self-interest. Compassion and solidarity may be more easily generated, as horrors unfold in Morocco and Libya.

But even now, responses to the plight of the poor and the homeless are split. On the Right, there is a tendency to see immigrants, especially when illegal, as violating the law and taking advantage of the wealth and order of societies which they have done nothing to create. On the Left, the aspiration remains for a borderless world, in which the poor, destitute, and displaced are free to enter and to stay in peaceful and economically developed countries. In all societies, working and lower middle class citizens, often hard-pressed, may resent recent immigrants lengthening queues for public housing, health and social services, and good school places.

In his Social Europe interview, Collier argues that former Chancellor Merkel “ignored the 2011 refugee crisis, woke up to it in a panic in 2015 and very irresponsibly and unilaterally opened the [German] door, thinking only ten thousand would come.” The million who did come panicked her again into “doing an incredibly expensive deal with President Erdogan (of Turkey)”—Turkey keeps potential future immigrants to Europe in camps and Germany foots the bill.

This, Collier believes, aptly illustrates the Western tendency to oscillate between unsustainable compassion and generosity on one hand, and reactive, panicky door-slamming in response to public outrage on the other. Neither extreme answers the desire for compassion or the pressure for entry. Only by understanding this can a long-term resolution be found that makes sense to both sides and gives migrants real assistance.

The developed world, he believes, must break its habit of self-congratulation when it brings in well-trained doctors, engineers, and IT specialists from Africa and SouthEast Asia. This is a warning especially for the UK, where it is often a matter of preening that the Prime Minister and much of his cabinet are the children of immigrants. Rishi Sunak was born in England to parents of Indian descent who came to the UK from East Africa; Home Secretary Suella Braverman was born in England to a Mauritian mother and Kenyan father, both immigrants; Business and Trade Secretary Kemi Badenoch was born to Nigerian parents in England; and Foreign Secretary James Cleverly’s mother is from Sierra Leone.

Collier sees the large numbers of African, Middle Eastern, and Asian professionals in British institutions not as evidence of a lack of racism in British society (though a recent report finds that the UK is among the least racist societies in the world), but as a selfish grabbing of highly skilled men and women who are needed much more in their own countries. “People think,” Collier observes, “that they are doing some great and noble act, luring bright young people away from their real obligations and opportunities in Africa. … It’s actually very sad that people define themselves by an aspiration to get out of their country. And inadvertently, Europe is in danger of doing that with Africa.”

At the 2016 London Pledging Summit, a “Jordan Compact” was agreed, in which finance and trade concessions were granted to Jordan in exchange for that country providing work permits to Syrian refugees. The scheme was the brainchild of Collier and his Oxford University colleague Alexander Betts. They had visited Jordan and realised that the country would take thousands of Syrians but would not allow them to work, since refugees accustomed to low wages would severely undercut Jordanian workers, whose average wages are some ten times higher. The migrants were thus safer than they had been, but without any way of making a living or contributing to the society in which they now resided.

The solution was the creation of Special Economic Zones, into which foreign companies would be invited to set up manufacturing companies, where the refugees could legally work and Jordanian workers would not be undercut. Some 180,000 Syrians now received work permits, in a country where they had hitherto been denied the right to work. A later report concluded that the results of the initiative were mixed: the Syrians could work and wished to, but few foreign companies were prepared to participate. Most of the companies created were Syrian and in the garment sector. They mainly employed women and not many Jordanian workers wished to work there “for a range of reasons.” The Compact has, however, been used as a template for other African states to grant at least a limited right to work to refugees.

The basic insight driving Collier’s work is that immigrants, whether they are refugees from danger or people simply seeking a better life, need not compassion but physical safety and job security, while Western states short of highly trained professionals need to stop “luring” these workers from poor and developing states and invest more in training their own young people. (Collier believes that the British Medical Association, the doctors’ trade union, has deliberately curtailed the supply of doctors, because it has “found it very advantageous to keep their numbers of British doctors very small so they got the plum jobs.”)

In his best-known book, The Bottom Billion, Collier writes that “within the societies of the bottom billion there is an intense struggle between brave people who are trying to achieve change and powerful groups who oppose them … the struggle for the future of the bottom billion is not a contest between an evil rich world and a noble poor world. It is within the societies of the bottom billion and to date we have largely been bystanders.”

The certainties of Left and Right, each of which sees the other side’s position on immigration as foolish if not evil, are an easy luxury for “bystanders.” The societies of the most wretched of the earth must convince their citizens to stay, bring corruption under control (the bottom rungs of the Corruption Perceptions Index are overwhelmingly occupied by African states), and make clear to Western states what they need for economic development. If they do not, the future of the immigration crisis is likely to involve more than mere scuffles between immigrants and the police on the crowded island of Lampedusa.