The New Right’s Political Insurgency

Liberals have been slow to understand the frustrations fuelling the rise of the New Right.

Within democratic states, a battle is being fought over the meaning of conservatism. A populist attack on the prevailing liberal consensus is being led by insurgent nationalist parties with a counter-liberal ideology hostile to—or at least deeply suspicious of—free trade, mass immigration and multiculturalism, foreign intervention, and supranational organisations and bodies, including the EU. Although their nationalist rhetoric, and their emphasis on family values and the importance of tradition, place these parties on the cultural Right, their rhetoric on economics and class draws on the legacy of the Old Left. As a result, they have been drawing support from working- and lower-middle-class constituents, some of whom have voted for social-democratic, socialist, and even communist parties for generations.

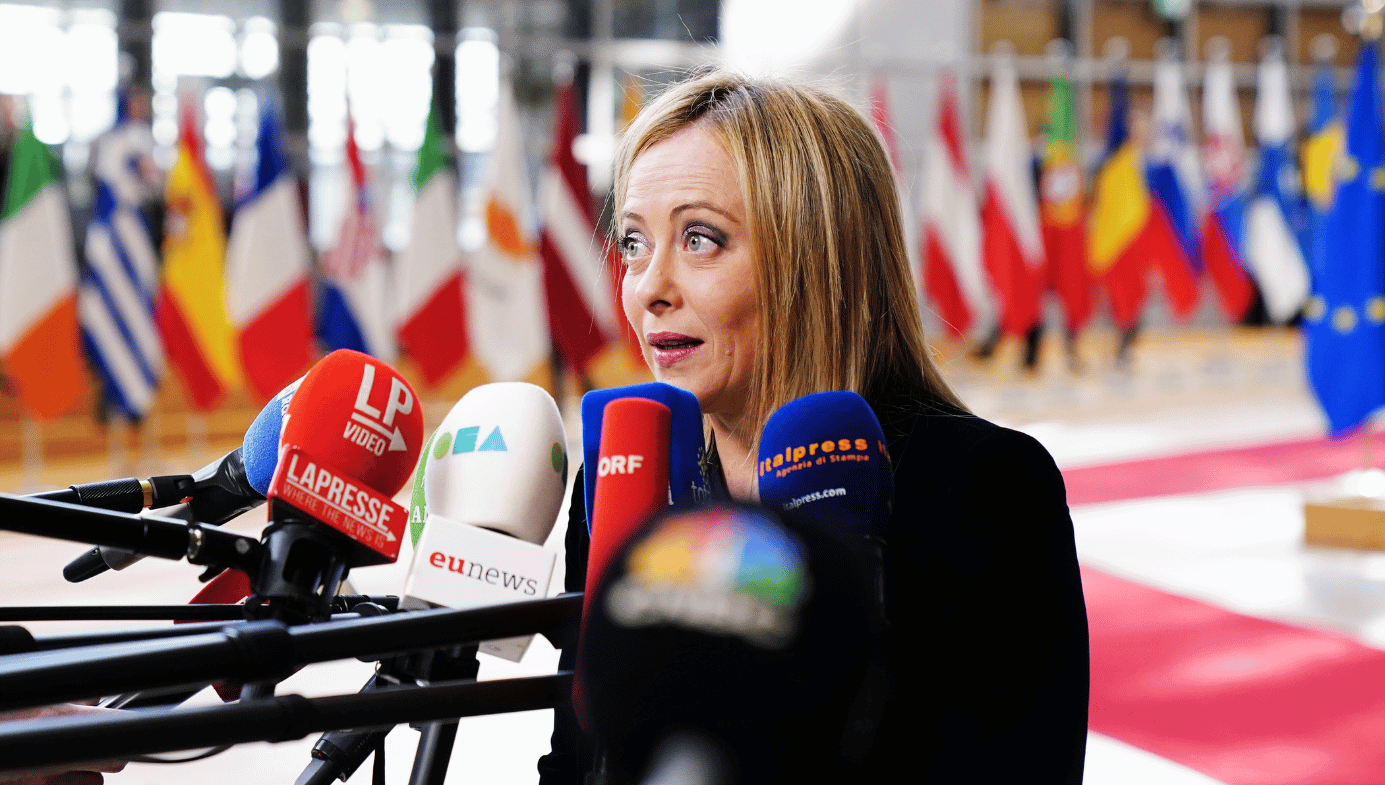

For the time being, the insurgents are—for the most part—winning. This is a potentially consequential shift at a time when established political commitments everywhere are facing disruption. In the Swedish and Italian elections last September, the New Right won significant victories. In Italy, they became the government, and Giorgia Meloni, founder and leader of the Fratelli d’Italia, was installed as prime minister. The Sweden Democrats, meanwhile, until then shunned by all other parties in a state usually governed by social democrats, became the largest party on the Right. By agreement, they took no ministries, but they were put in effective charge of immigration and law and order policies, which had been critical to their electoral success.

In Sweden, the populist gains have produced a somewhat paradoxical effect. During a recent interview, the leader of the Sweden Democrats, Jimmie Åkesson, counterposed liberal Swedish values, policies, and laws with far more conservative beliefs and practices prevalent among devout Muslims: “It’s difficult to be considered Swedish for more ‘fundamentalist’ or ‘fully practicing’ Muslims. … If you are a fundamentalist Muslim, you also tend to have values that we do not associate with modern society … the view of gender equality, how to raise children, the view of animals and such, it differs … it is difficult to be considered Swedish by other Swedes.”

At the same time, immigration to Sweden has become significantly more difficult, even for Ukrainian refugees. In April, Åkesson made a series of demands in various interviews: asylum seekers should be processed in countries outside the EU (such as Rwanda); the EU’s migration pact should not be permitted to become Swedish law; and the government should have the right to influence cultural events (such as drag shows) paid for by the taxpayer. His criticism of the EU has, naturally, been scathing, and he has raised the possibility—set aside before the September election—of “Swexit.”

The new Italian prime minister was raised by a single mother in the working-class Garbatella area of Rome. She believes that her focus on the family, patriotism, and faith resonates better with the lower social classes than the agenda of a Left now more interested in cultural issues than in understanding the economic needs and the beliefs of those they used to represent. The September 2022 elections in these two states have brought them closer together, and Meloni visited Sweden in February to discuss common policies on immigration.

Sweden and Italy have also forged closer ties with the populist governments of Hungary and Poland. Poland faces a general election in the autumn, and the governing Law and Justice party presently shows an eight-to-10-point lead in the polls over the liberal-centrist Civic Coalition. In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz is now 30 percent clear of the leftwing Democratic Coalition. Orbán has been something of a mentor to the other New Right leaderships, especially Meloni, although it is unclear if that relationship will continue.

These parties can now bring government power to bear on their proposals and actions. The new Italian government depends on the EU for around €200bn (money that Italy is finding hard to disburse “due to its elephantine bureaucracy, limited human resources, and a general administrative and political system unfit to manage such a vast task”) and Italy’s membership of the euro currency makes an “Italexit” economically unrealistic. Nevertheless, Italy quietly agrees with Sweden, Poland, and Hungary on the need to oppose further integration and to undo some of the integration already achieved, thereby returning power to national administrations.

These parties are buoyed by the growing popularity of New Right parties in opposition elsewhere. Marine Le Pen, leader of France’s National Rally (Rassemblement National) is now the most popular politician in France, benefitting from President Macron’s slump in the polls and from his prolonged struggle to raise the pensionable age from 62 to 64.

During Finland’s general election in April, the Finns Party came in only two seats behind the victorious National Coalition Party, which remains hesitant about forming a coalition with the Finns, even though it needs them for a parliamentary majority. Support for the Finns dropped after a period in coalition from 2015 to 2017, but has revived under the leadership of Riikka Purra, nicknamed the “vote queen” of the election. Her party is now challenging the National Coalition and the Social Democratic parties for first place, and has established itself as the natural home of working-class voters. Its new popularity was achieved by turning to the right when out of power, and placing opposition to immigration at the centre of its platform.

The Alternative for Germany (Alternativ für Deutschland) party has fallen in the polls over the past year, but at 16 percent of the vote, it still beats the Greens (which are part of the governing coalition) and sits only three points behind the Social Democratic Party (which leads that coalition). The AfD, like the Finns, has also taken a turn to the right under the influence of Björn Höcke, leader of the Thuringia branch of the party. Höcke has been accused of using rhetoric that recalls the Nazi period:

Höcke has called for a “180-degree turnaround” in the way Germany looks at its past, and he regularly uses expressions like “degenerate” or “total victory” in his speeches—despite the fact that as a former history teacher he knows full well which dark chapter of German history he is conjuring up.

Axel Salheiser, a right-wing extremism researcher in the eastern German city of Jena, says the speeches that Höcke and many other AfD politicians deliver are riddled with words and phrases “confusingly similar” to those used by the Nazis.

In Denmark and Greece, the governing parties have adopted harsher measures to deter immigration, now likely to be copied by other states. Greece’s centre-right New Democracy party won the most votes in the election earlier this month but did not manage to secure a majority. In response, it has toughened up migrant control after camps set up on Greek islands degenerated into squalor. In Denmark, the ruling Social Democratic party has likewise hardened immigrant legislation, and subsequently won the election in November 2022.

The New Right parties believe they have found fertile ground on which to build larger constituencies. They appeal to, but also inflame, the grievances of men and women from the lower social classes who are struggling to maintain decent lifestyles. Pew polling shows that immigrants who come to work legally, and who wish to integrate into social and working lives, are welcome, but that opinion about illegal migration is far more negative:

Even though many people in the [European] nations surveyed say they want less immigration, there is considerable support for accepting both refugees who flee violence (a median of 77%) and immigrants who are highly skilled (64%). At the same time, large shares back deporting immigrants currently in the country illegally (a median of 69%).

However, Pew also found that:

European publics tend to want less immigration. A median of 51% believe their country should allow fewer immigrants or none at all, while 35% think the number of immigrants should stay about the same. Just 10% want more.

Governments that tighten controls and/or promise to reduce the flow of migrants gain electoral points. This helps to explain the spread of restrictionist policies, which may or may not follow EU practice, and which are making the prospect of efficient continental coordination increasingly unlikely.

Absent some unforeseen change, migratory pressure is all but certain to increase, and most migrants will try to enter the wealthier countries of Europe, North America, and Australasia. Many of these states have ageing populations and a birthrate below replacement levels, so they need immigrants to maintain the workforce, services, and tax intake at current levels. European states will be caught between the rock of a declining population and the hard place of unpopular annual migration surges. Populists have been slow to address the former, even as they aggravate anxieties and fears about the latter with conspiratorial theories of elite malevolence. One or another version of “replacement theory”—which holds that elites are deliberately increasing immigration to suppress wages and gain political support—has now been widely embraced among US Republicans and is growing in Europe.

Rising poverty in Africa and the Middle East, civil strife in Latin America, and resentment of the rich by the poor are all likely to throw Western governments back on enhanced strategies for blocking immigration. Many states are already putting these into place or planning to do so. The New Right parties argue that the competition for health, social services, and education has already become appreciably sharper and that pressure on all three will only increase as migration figures continue to rise. They have refocussed attention on the plight of towns and regions that have endured forced de-industrialisation, where high-paid and skilled jobs have been replaced (if they have been replaced at all) by lower-paid service jobs. Many liberal commentators and politicians have been slow to understand these frustrations, and have sought to stigmatise New Right parties as “fascist” instead, blaming populist politicians for the growing revulsion against conventional centre-left and -right administrations.

This is what lies at the root of the febrile politics in Europe and North America, where often inchoate but increasingly powerful movements are rising to governance. Britain has not yet developed a New Right party, but it may now follow the European example as populists like Nigel Farage seek to blame the deleterious economic effects of Brexit on an establishment too incompetent to deliver its expected dividends. A poll in the Daily Telegraph last November reported that many millions of voters would consider supporting a new party led by Farage, even though he remains coy about taking a decision to establish one. The most popular reason for such support was that “we need someone to stand up for ordinary British people.”

‘Brexit has failed’ GB News presenter Nigel Farage admits after he is read a list of negative facts about the UK economy https://t.co/P0zxS1DNGF pic.twitter.com/mUrnHee5mb

— BBC Newsnight (@BBCNewsnight) May 15, 2023

New Right policies are substantially the same wherever they attract support—opposition to the EU, distrust of globalisation and corporations, dislike of mass and illegal immigration, support for families and local communities, aversion to the “woke” phenomenon and to cancel culture (at least when it is employed against the Right), and wariness of the claims of LGBTQ lobbies. But each iteration of this populism is a product of its own political culture, and varies from the relatively liberal Sweden Democrats to the harsher rhetoric and beliefs of the Alternative for Germany. There has been too little time to judge how far the new governments of Sweden and Italy will go in pursuing hardline policies which, in both cases, they claim to have substantially softened.

More importantly, none yet, in or out of power, has faced up to the responsibility their growth has bequeathed them—that is, to develop proper planning for the large dilemmas now facing the world, especially the rich world in which most have grown. It will not be enough to simply erect larger and less porous barriers to keep poor and often desperate men and women out of their relatively comfortable homelands. Only by displaying in their deeds a sincere attachment to democratic forms and substance will they deserve to represent the millions for whom they claim to be the champions.