Politics

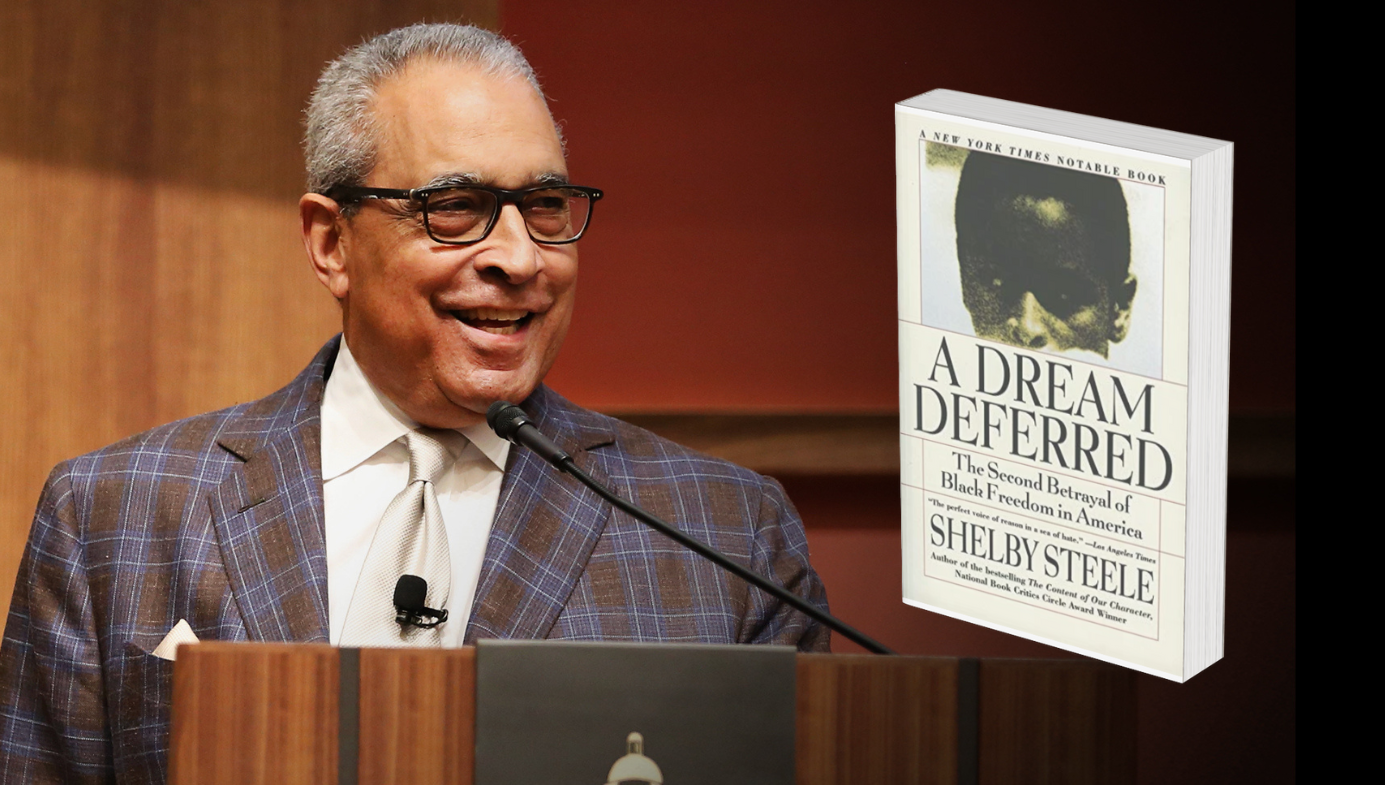

‘A Dream Deferred’ Revisited

Shelby Steele’s masterful second book invites black America to reject redemptive liberalism and the helplessness it demands for a humanistic politics of advancement.

“The second book you publish,” Shelby Steele’s editor once told him, “is the hardest one you will ever write.” In Steele’s case, it turned out to be his best. After the publication of The Content of Our Character: A New Vision of Race in America in 1990, Steele found himself in the intellectual spotlight on the most contentious issue in the country. That experience changed his life. “Ultimately, what I found after The Content of Our Character is that people wanted more, wanted me to go further,” he told me earlier this year. “So that became the struggle. I had to go deeper to get to material and get my own thinking onto a different phase.”

The success and attention Steele received, however, came at a steep price. He was ejected from academia after a 20-year tenure at San José State University as an English professor, and he became a pariah to the post-1990s civil-rights establishment. He lost a number of friends and found that his university lectures were now routinely shouted down by students. “My career in universities sort of ended at that point, involuntarily,” he recalls. “The campus I taught on for many years sort of canceled me. I brag today [that] I was one of the first canceled people.” These unwelcome developments resulted in his second book, A Dream Deferred: The Second Betrayal of Black Freedom in America, in 1998—an extended reflection on his new role as a black conservative in America’s cultural landscape, and on the country’s racial iconography and moral psychology. “So, all these things I had to absorb and understand. It was a difficult, alienating period of my life that now, in retrospect, I’m grateful for.”

Steele was an unlikely black conservative. He was born in 1946 near the South Side of Chicago to an integrated family of civil-rights activists. His early upbringing saw the end of segregation, the successful passage of key civil-rights legislation, and the dawn of a new America. His parents, Shelby Sr. and Ruth Steele, were both pillars of their community and founding members of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality. Consequently, young Shelby spent much of his childhood attending protests to integrate public institutions. Forced into an all-black neighborhood and subpar schooling, he was subjected to all the indignities and humiliations of living on the wrong side of the color line in a separate and unequal society.

By the time he arrived at Coe College in 1964, Steele was shifting away from the nonviolent principles of his parents and steadily transforming into a race man, growing out a big afro, leading multiple student protest groups on campus, and grounding himself in the post-integration black-power politics of the moment. After graduating college, he worked in some of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty programs in East St. Louis, helped to develop some of the first black-studies curricula, and even traveled to Africa to visit countries newly liberated from colonial rule. But eventually, he became disillusioned with activism as he grew to appreciate the freedom and opportunity he experienced in America after the 1960s. By the time his first book was published, his parents’ classical, freedom-centered liberalism had become the new conservatism on the topic of race.

The Loneliness of the Black Conservative

The lengthiest essay in A Dream Deferred is titled, “The Loneliness of the Black Conservative,” and it is here that Steele first considered how he came to accept that unfamiliar label: “I realized, finally, that I was a black conservative when I found myself standing on stages being publicly shamed,” he wrote. His previous book had argued that racism was no longer the major issue for black people in America, and that America’s obsession with uncovering white persecution of blacks resembled an extension of the country’s stormy racial history, not a break from it. This view was considered heresy in many quarters.

As Steele “traveled around from one little Puritan village (read: university) to another, a common scene would unfold. Whenever my talk was finished, though sometimes before, a virtual militia of black students would rush to the microphones and begin to scream.” He was invariably accused of betraying his race. “My confronters were not freedom fighters; they were Carrie Nation-like enforcers, racial bluenoses, who lived in terror of certain words. Repression was their game, not liberation, and they said as much.” This outrage, Steele believed, illuminated an ironic reversal in the nature of black protest from the 1960s to the ’90s: “a shift in focus from protest to suppression, from blowing the lid off to tightening it down.”

While most students didn’t react this way, the very decency of the majority made the shaming of the minority more effective: “I learned what it was like to stand before a crowd, in which a coterie of one’s enemies had the license to shame, while a mixture of decorum and fear silenced the decent people who might’ve come to one’s aid.” In what Steele and his son would later refer to as “bathroom black,” many of these same confrontational students would meet with him in the bathroom after his talk to let him know that they agreed with what he said but that they were afraid to say so in public. “The goal of shaming was never to win an argument with me; it was to make a display of shame that would make others afraid for themselves, that would cause eyes to avert. … Shame’s victory was in the averting of eyes, the cowering of decency.”

Shame, in one shape or form is the likely fate of the black conservative. The label conjures a unique national archetype that appears to many observers to be a contradiction in terms. Although a great deal of viewpoint diversity exists within the black American community, nothing quite invokes the same incongruity as pairing black with conservative. “Most people could empty out half a room simply by saying what they truly believe,” Steele wrote. “If, somehow, you come by the black conservative imprimatur, you will likely empty a lot more than half before you say what you believe.”

“What, in fact, is a black conservative?” Steele asked. “Well, he is not necessarily a Republican, or free-market libertarian, or religious fundamentalist, pro-lifer, trickle-down economist, or neocon. I have met blacks in all of these categories who are not considered conservatives.” The term itself is something of a misnomer. As a consequence of America’s racial history and the triangulation of forces that opened the door to black freedom in the 1960s, Steele observed, the liberal-conservative axis is somewhat different for blacks than it is for other Americans. Because anti-racist activism gave rise to the Civil Rights movement and liberated blacks from second-class citizenship, black Americans had become tethered to a specific form of politics and activism that focuses exclusively on their group’s historical victimization at the expense of other forces and factors:

Certainly, no explanation of black difficulties would be remotely accurate were it to ignore racial victimization. On the other hand, victimization does not, in fact, explain the entire fate of blacks in America, nor does it entirely explain their difficulties today. It was also imagination, courage, the exercise of free will, and a very definite genius that enabled blacks not only to survive victimization but also to create a great literature, expand and deepen the world’s concept of democracy, influence popular culture around the globe, and so on. No people with this kind of talent, ingenuity, and self-inventiveness would allow victimization to so singularly explain its fate unless it had become a primary source of power.

What makes someone a black conservative is not a denial of white racism or black suffering, but a refusal to draw a straight causal line between the two. “Very simply, then, a black conservative is a black who dissents from the victimization explanation of black fate when it is offered as a totalism—when it is made the main theme of group identity and the raison d’être of a group politics.” A person can be liberal or progressive on policy issues and still be considered a black conservative if he dissents from the prevailing racial contract of majority guilt/shame and minority rage/indignation over past injustice. As Steele noted:

When victimization is treated as a totalism, it keeps us from understanding the true nature of our suffering. It leads us to believe that all suffering is victimization and that all relief comes from the guilty goodheartedness of others. But people can suffer from bad ideas, from ignorance, fear, a poor assessment of reality, and from a politics that commits them to the idea of themselves as victims, among other things.

Such a stance places the black conservative at odds with the moral authority of the group. “This authority is very often based on a strategic explanation of a group’s fate, a narrative that explains why the group is in a given situation and therefore why it is justified in pursuing a certain kind of power,” Steele wrote. “This explanation is all-important because it establishes the group as a collective being with a history, a present, and a future—a life, as it were, that entitles it to all the considerations of sovereignty. ... In the schools of every nation, children hear the story of their country’s struggle for sovereignty. But for a minority group like American blacks, whom history has left with a deep sense of vulnerability, shame becomes a primary means of reinforcing the group’s story.”

Steele elaborated on the shaming power of groups as it pertains to the black conservative predicament:

The Czech writer Milan Kundera—a man whose experience under the hegemony of the Communist Party taught him much about the shaming power of groups over individuals—says that shame transforms a person “from a subject to an object,” causes them to “lose their status as individuals.” And to suffer this fate means that the group—at least symbolically—has determined to annihilate you. Of course, we have no gulags in black America, but black-group authority—like any group authority—defines itself as much by who it annihilates as who it celebrates. Thus it not only defines group, it also defines grouplessness. And here, on this negative terrain, where his or her exclusion sharpens the group identity, the black conservative languishes as a kind of antithesis.

It is for this resistance that black conservatives are stigmatized in the American imagination as “race traitors” and “Uncle Toms.” Epithets like these imply a lack of group loyalty, cunning self-interest, and even racial self-hatred. “And this is the most constant charge against the black conservative—that he does not love his own people—an unpardonable sin that justifies his symbolic annihilation. Because the capacity to love makes us human, it is precisely the charge that he is without love that transforms him ‘from subject to object’ and causes him to lose his ‘status as [an] individual.’”

A Dream Deferred

Throughout A Dream Deferred, Steele mapped the cultural territory enveloping the black conservative archetype and race in America more broadly—the set of taboos, stigmas, and unconscious fears and longings that enforce conformity on race issues and prevent an honest accounting of American inequality. Under what Steele called “redemptive liberalism,” policies around race are pursued less for what they accomplish than for what they represent, and anyone who stands in the way of said redemption is stigmatized as either a racist (if you’re in the majority) or a race traitor (if you’re a minority). When a country has committed a grand act of historical evil and is then forced to reckon with that evil, there arises a deep and urgent need among its citizens and, importantly, its institutions, to be morally redeemed of its past and forge a new identity of national innocence. As Steele explained:

This formula always begins the same way: a society runs into a problem that shames it. At the turn of the century it was the inequities and backwardness of a society stuck in czarist imposed feudalism—against the backdrop of a rapidly modernizing Western Europe—that brought shame to Russia. In Germany it was the grating shame of defeat in World War I, the specter of a great power humiliated. In the United States it was the shame of three centuries of virulent racial oppression that contradicted every principle the society supposedly stood for. These societies then conjured ideas-of-the-good that they hoped would redeem them from shame. Against the inequities of feudalism Russia would have a ‘classless society.’ Against its post-war lowliness Germany would have Aryan supremacy. And against the shame of American racism there would be a new ‘multicultural,’ ‘inclusive’ ‘diversity.’ Always the idea-of-the-good contrasts the specific shame the society is dealing with.

As a vision for what is redemptive for the shamed society, this idea of the good has three specific qualities: It simplistically demarcates good from evil so that all who disagree with it are aligned with evil and against their nation's redemption; it is so vague that it imposes no serious accountability, sacrifice or principle on those who support it; however, it always requires governmental and institutional interventions, if not new governments altogether. This kind of ‘good,’ of course, is a recipe for power.

Importantly, in the American case, “these ideas do not respond to black need; they respond to American shame. They treat the nation’s shame, not the people whose suffering shames the nation.”

The burden of human freedom and responsibility is a major theme in Steele’s work, and in A Dream Deferred in particular. In that book, he outlined human agency as responsibility combined with possession. “You have agency over something … when two things are true: You have the freedom that allows you to be responsible for it, and you accept that this responsibility belongs to you and not to someone else.” Steele offered the example of an American slave, who will ”certainly suffer in his life, but the very nature of his dehumanization is that he has no freedom in which to assume responsibility for his life. Nor does he truly possess his life, since he literally belongs to others. But once in freedom, suffering is the surest indication of where agency ought to be, of where responsibility ought to be accepted.” This is what makes freedom a “burden,” as the existential philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre famously put it, in that it “removes the obstacles to responsibility, so that if we do not accept it, we stand accused.”

“We all, as individuals and groups, have an ambivalent relationship to agency,” Steele continued, “because it is always a call to the will. To be free, and to have ultimate responsibility for a problem, is to be called upon to exert one’s will to resolve it. … Thus one of the most common dodges in the human experience is to deny agency by denying freedom. … Often we escape freedom by saying that others are to blame for our problem, and therefore they have agency over our problem and must exert their will to solve it.” [italics in original] While this ambivalence toward freedom and responsibility is all too human, Steele argued, it has had a particular impact on the black American community after the civil-rights victories of the mid-20th century.

“To put all this another way,” Steele wrote, “there is something at work in our time that has broken the archetypal relationship between suffering and responsibility in the area of race.” Throughout human history, suffering has been an incentive to change and grow. “Suffering, whether caused by fate or injustice, has always been the most common spur to agency over one’s experience,” Steele wrote. “When we get to the point where suffering doesn’t prod us to take agency over our lives, then we are cut off from the meaning of suffering—which is to be cut off from the meaning of reality.” There is nothing worse than to suffer without learning. Not only is that suffering bound to continue, but other people generally lack sympathy for those who don’t learn from it.

Steele argued that redemptive liberalism has not permitted black Americans to benefit from their collective historical experience. Its reigning ideas-of-the-good only reward black victimhood rather than what can be achieved and what has already been achieved. “For the sake of its redemption, the United States has needed black suffering to be a helpless suffering, a suffering in which the exercise of our will is essentially futile. Only this kind of suffering is contingent on the good will of white America to redeem itself. … This is how redemptive liberalism steals the meaning of black suffering away from blacks.”

It wouldn’t be enough for Steele simply to criticize things as they are without offering some vision of how they might otherwise be, and he was not naive about the challenges we face as Americans. Steele briefly discussed the struggle of other groups to make meaning of their suffering after their oppression has come to an end:

In thinking about all of this I am reminded of a passage by the Italian writer and Holocaust survivor, the late Primo Levi, in which he describes what it was like to be liberated from the concentration camps. He makes the point that there was not much happiness in liberation, that “almost always it coincided with a phase of anguish.” He says of those liberated, “Just as they were again becoming men, that is, responsible, the sorrows of men returned.”

It is difficult to confront the idea that once freed from profound and unjust suffering and dehumanization, the human being remains responsible and the journey has only just begun to regain his full humanity. Freedom, as Steele has written elsewhere, especially for members of a group that’s been historically mistreated, is experienced as a kind of shock or even a humiliation. It comes with a terrible and weighty responsibility that didn’t exist in oppression.

In A Dream Deferred, Steele argued that social reform in America should be thought of as an initiation into adulthood, which spares us the symbolic quest for redemption and lets us focus on practical realities that impact everyday lives. This quest has also kept the majority from undergoing its own initiation into Americanness. Instead of reflecting on our history at the level of human experience, we compulsively attempt to abstractly absolve ourselves of it through moralistic politics.

We can’t fix our history, Steele insisted, because it is who we are. We cannot regain our innocence, for we are human beings and no one is innocent. The Civil Rights movement should have disabused us of the idea that we can fix our history or reestablish a lost innocence. The only way to cut the cord between race and power in America, he argued, is by returning to the same democratic and humanist principles that allowed the Civil Rights movement to occur in the first place: fairness by individual rights, opportunity by freedom, advancement by merit, equality by individual rather than by group. “In American life race will always be an opportunity for evil. … Only the separation of race and ethnicity from public entitlement and an insistence on the freedom of the individual will curb the evil and license that always follows race into public life.”

Over the past 30 years, Steele has argued that race is almost always a corruption, a mask to hide our true motivations and selves. “Wherever we self-consciously use race—whether out of hate or love—as a tool, a convenience, a proxy for disadvantage, a currency of entitlement, a means to power, a basis for group preferences, then we are using it precisely to gain the license to break the normal human and democratic principles we live by for some ulterior reason.” This is how we end up in a situation where things mean the opposite of what they say—where a word like “diversity” actually means fewer whites, where “inclusiveness” implies another form of exclusion, and where “antiracism” starts to look and sound just like racism—a means of judging individuals by their skin color instead of their character.

For Steele, the post-Civil Rights era, despite its many positive developments, has been the saddest period in black American history. “The only way out of this situation,” Steele wrote, “is to use a strictly human analysis of our social problems, even when those problems are caused by race. This means simply seeing those who suffer social problems as first of all human beings and American citizens, so that whatever the source of their problems may be, their needs are understood to be human and not racial. The United States should now be racially experienced enough to understand that a multi-racial democracy simply cannot have an obligation to meet the racial needs of its citizens; its only obligation can be to address their human needs without regard to race.” [italics in original]

Suffering and What We Make of It

A Dream Deferred is my favorite of Steele’s books because it provides the deepest account of his ideas. The pain and stress produced by the success of his first book found expression in his second. “In A Dream Deferred,” Steele told me back in January, “I was really scratching in that territory for the first time. To go against the black identity at that moment, as someone like me from my background who grew up in segregation, I was somehow giving the back of my hand to black people. That’s how they took it. Still do. A Dream Deferred really meant something to me—I began to understand the pitfalls of identity. So that was a hard book to write and it took a long time but I’m grateful for it.”

So am I. Innocence, shame, ideas-of-the-good, freedom and responsibility, the symbolic quest for redemption and moral authority, the moral psychology and iconography of race in America—the ideas developed in A Dream Deferred are where Steele really thrives. He is at his best when discussing the particular and peculiar psychology that emerged around race after the 1960s, right when you might expect that the importance of race in American political discourse would begin to decline. Steele has done a better job than anyone else at marking that mid-20th-century cultural shift and its consequences. As he says in the preface, “If there is an insight that unifies the essays that comprise this book, it is that America’s collision with its own racial shame in the civil rights era is the untold story behind today’s polarized racial politics.”

I’ve never encountered a writer with such prescient instincts. Steele’s civil-rights background uniquely positioned him to be a critical voice in American social discourse, but it did not turn out to be the one he might have expected. When I asked Steele where his sense of optimism comes from, he credited his activist parents for the courage they instilled in him.

“My father was born in the Deep South, third grade education, truck driver, taught himself to read and write. My mother had a master's degree from the University of Chicago, from the middle upper class around Cleveland, Ohio. Her father was a building contractor. They loved each other. They got married, had children. They met in the Civil Rights movement. They had faith. An interracial couple in the 1940s. They didn't miss a beat, they were like stars in the neighborhood. People looked up to and admired them. They went to a segregated church, convinced the minister to break off and start a new church. Swept through the community. They closed down my elementary school because it was segregated.

“So they were activists on a high moral plane, yet very down to earth, very real. With parents like this I wasn’t afraid of anything. I had the arguments with which to defend what I was doing, to stand on my own. That was my big advantage in life. I was in favor of integration when people were afraid of integration, blacks as much as anyone. I could explain why integration was healthy, was a good thing. These were rare ideas at that time in our history. It was clearly my parents who gave me this sense that you keep the faith, you be happy in your resistance. They were happy people. Their belief system was consistent with the life they were living. I could take risks in my thinking that other people were afraid to take. I never had to conform. It gave me a freedom to look at things and be open to ideas and the world in my own way.”

If Steele were just reiterating up-by-your-bootstraps arguments, his first book would have passed under the radar without comment. But that’s not what happened. The almost unfathomably harsh reaction he has received for making his arguments in public deserves sober consideration. Such is the cost of the black conservative label. In many ways, Steele was a man ahead of his time, and there’s still time yet. He’s been working on a documentary with his son Eli as well as another book for a contemporary audience that hits similar notes to his second.

Ultimately, the issue of race in America is about suffering and what we make of it. It is obvious that human suffering is not evenly distributed in this life. There are disparities and inequalities of human suffering everywhere, whether they arise from the cruelty of circumstance or nature, and much of our culture and politics emerges to come to terms with this difficult fact. Race is merely one way to make sense of suffering, and it has become the deepest and most contentious issue in America’s politics because it is so intertwined with our national and moral idea of ourselves.

But race is not a good proxy for human suffering in America. None of us can answer for the suffering of our history. It’s enough to simply be mindful of the suffering of the present or of our own suffering or of the person right in front of us. Suffering is felt on a human level beneath the skin and that is where our care and concern ought to lie. It is time to walk away from our past into the vast and frightening future for which none of us is prepared.