Nations of Canada

The Quest for Pelts

In the ninth instalment of an ongoing Quillette series on the history of Canada, Greg Koabel describes how the late 16th-century fur trade developed amid a disrupted Indigenous geopolitical landscape

What follows is the ninth instalment of The Nations of Canada, a serialized project adapted from transcripts of Greg Koabel’s ongoing podcast of the same name, which began airing in 2020.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, two separate yet related developments took place in what would become eastern Canada. The first was a sudden explosion in exchange between European traders and Algonquin-speaking fur trappers on Canada’s Atlantic coast. French, English, and Basque visitors had long been doing a decent side business while pursuing their main purpose of fishing or whaling, exchanging iron tools or scrap metal for animal skins. However, the 1580s witnessed a significant increase in the scale of this trade. For the first time, ships were sailing across the Atlantic for the express purpose of procuring furs.

Meanwhile, for the Innu and Mi’kmaq living along the Atlantic coast, the period brought the beginning of a dramatic change in economic and social conditions. For decades, they too had seen the fur trade as a supplement to the seasonal exploitation of fish and game resources. But now a new economic model was becoming viable. And in many ways, it was more attractive than the old model.

Time that had previously been spent fishing, hunting caribou and other game, or crafting stone tools and pottery, was now better spent hunting the animals that Europeans were interested in, such as lynx, fox, marten, and, most of all, beaver. Those skins could be traded for food, metal tools, and copper kettles far in excess of what domestic production could manage. In microeconomic terms, they were leveraging the power of comparative advantage.

However, it was not all good news. The more dependent on European trade these peoples became, the more susceptible they were to abrupt swings in the European fur market, not to mention the political and military pressures that European powers were able to apply.

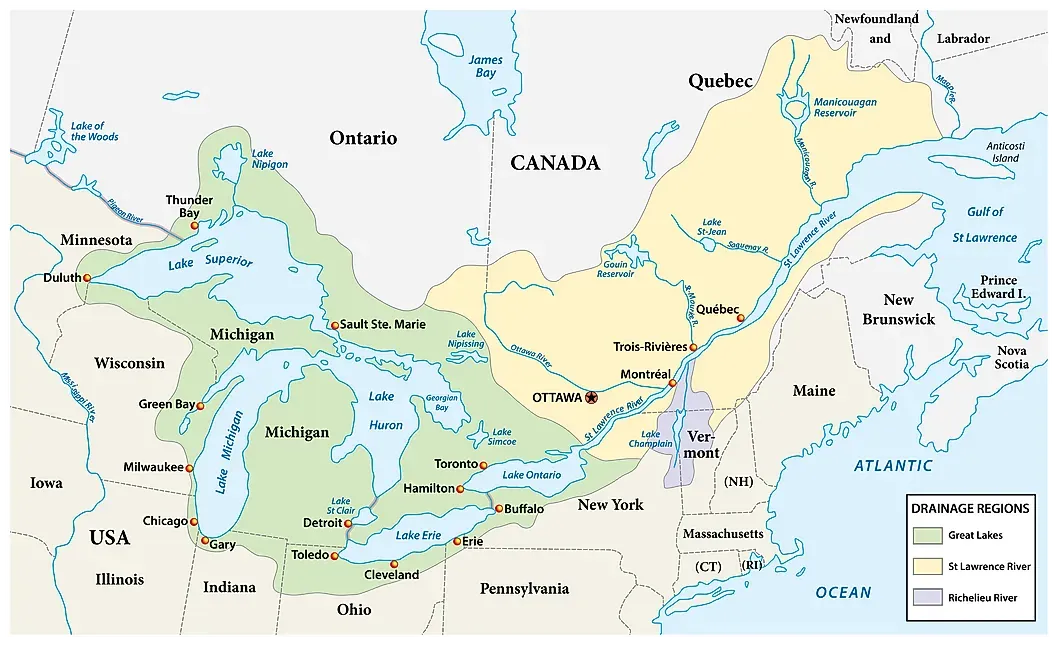

The second development took place a few hundred kilometers inland, up the St. Lawrence River that Jacques Cartier had explored (and named) a half century earlier. The main Indigenous players in this narrative were the same ones whom Cartier met at Stadacona and Hochelaga (modern Quebec City and Montreal, respectively). Or, more accurately, their children and grandchildren.

There’s no record of any European following Cartier up the river for about a generation after the failed French colonization attempts of the 1540s. So researchers have had to reconstruct the events that followed through a mixture of archaeology, historical hearsay, and guesswork.

The upper St. Lawrence and Great Lakes region witnessed massive turmoil in the decades that followed Cartier’s visits—so much so that by the time the French visited the area again at the end of the sixteenth century, they found a political landscape that Cartier would have found unrecognizable.

One of the more important debates among historians is whether these two stories were related to one another. Did European demand for fur send shock waves through the economic and political networks of eastern Canada in the late sixteenth century? Or were the Iroquoian speakers of the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence region being affected by their own historical currents, which were only marginally affected by Europeans at this point.

Historians have traditionally assumed that European contact must have been the dominant factor. In the absence of any other documented explanations, the thinking has gone, the draw of European commerce must be taken to be the most logical explanation for the geopolitical changes that disrupted Indigenous communities—especially given what we now know about the enormous role Europeans would play in the seventeenth century and beyond.

But archaeologists, who are less constrained by the limits of documentary evidence, present a different narrative of events. They have found little evidence that the economic changes happening in the Maritimes had much effect on life in the upper St. Lawrence or Great Lakes. Instead, they generally view the turmoil of the second half of the sixteenth century as rooted in long-running conflicts within the Iroquoian confederacies.

But first, let’s take a look at the fur trade. Why did Europeans suddenly become interested in North American creatures such as the beaver?

In fact, beaver pelts already had a long history as a valuable commodity in the European market. Up until the late sixteenth century, however, buyers had not been looking west, across the Atlantic, but east to Russia, where the Eurasian beaver (a species that is now nearly extinct) was hunted for its prized fur.

A beaver’s winter coat consists of an outer layer of long, coarse hairs that guard against water and dirt, and an inner coat of fine inner hairs that act as insulation. That’s not a unique fur system among animals. What makes the beaver special is that those inner hairs are ideally suited for making felt. They are remarkably resilient, and can withstand the strenuous working and re-working that felting requires far better than other furs.

This made beaver fur particularly sought after by hatters, who worked with large quantities of felt. In fact, the hatters sat at the end of a long supply chain that began in Russia. Removing the outer guard hairs of a beaver pelt without damaging the valuable inner hairs was delicate work. And Russians treated the process as a trade secret, tightly controlling exports out of the Baltic Sea port of Narva.

The fishermen and whalers who’d been plying the Canadian coast for much of the sixteenth century recognized that the furs the locals offered up for trade were an alternative source for beaver pelts. What’s more, the Innu, Mi’kmaq, and other Indigenous peoples who dealt in furs had discovered their own effective technique for removing guard hairs.

“Technique” is probably not the right word, however. It was customary for Indigenous peoples to turn beaver furs into coats, which would eventually wear thin after a year or two. For your average Mi’kmaq garment wearer, this was the end of the story. For the keen-eyed European fisherman, however, this was just the beginning: Months of continuous use and friction usually wore the guard hairs away. And so by the time the coat had lost its value to the Innu, it had became a great prize for the Europeans. In effect, the people of the Maritimes were achieving through hours and hours of daily life what Russian craftsmen achieved through focused expertise. It was, by necessity, incidental labour. If you actually paid someone to work over beaver pelts in the same way, the cost would have been astronomical.

Despite the happy discovery of feltable beaver furs in Canada, however, the fur trade was conducted on a relatively small scale for almost a century following the first sustained European contact. As noted above, Basque, French, and English visitors bartered for furs only as a complement to their primary activities of fishing and whaling.

In any case, the Innu and Mi’kmaq traders could not match the volume put out by the Russians at Narva. They were exchanging their worn-out coats in ad hoc meetings with fishermen, not gearing their economy and society toward fur production. At least, not yet.

Nor was there much infrastructure back in Europe to support large-scale fur commerce in this part of the world. The merchants and companies that specialized in the fur trade were all eastern-facing, their networks concentrated in the Baltic. And the ports that outfitted voyages to the Canadian coast, such as Saint-Jean-de-Luz and La Rochelle, had little experience dealing with furs.

Nevertheless, the foundations of a larger market were being built. This required the Europeans to adapt themselves to Indigenous methods of trade, which differed from the purely transactional economy of the early modern urban bourgeoise back in Europe. Trade with the Indigenous Maritime populations took the form of a free exchange of gifts between friends. The line between personal and commercial relationships was blurred, and trade agreements often were solidified by ritual adoption into a tribe, or even marriage.

The character of Indigenous commerce grew out of the pre-existing trade links between the various groups that populated eastern Canada long before the arrival of Europeans. Located deep in the interior of the continent, the Wendat Confederacy (later to become known as the Huron) conducted a thriving trade with the Algonquin-speaking hunters who bordered their lands. Mutual hospitality and kinship ties were crucial to these trade networks. Being a generous host won a man tremendous prestige within his community, and a bond of kinship was the only way to ensure the safety and security of traders travelling far from home.

The fishermen and whalers who crossed the Atlantic every year developed a certain familiarity with this (to them) alien approach to commerce. For instance, changing your price due to shifts in supply or demand might make sense to the market-oriented mindset of a trader in La Rochelle. But it could be seen as offensive to an Innu counterpart who read the smaller gifts on offer as a sign that their friendship was suddenly less valued than it had been in the past.

In addition to learning the metaphorical language of Indigenous commerce, the European visitors also had to pick up the actual languages of the Algonquin speakers. Again, pre-European trade relationships provided a head start. Although Algonquin speakers all belonged to the same broad language group, not every tongue was mutually comprehensible—even putting aside the Iroquoian speakers further inland. And so most groups had adopted so-called “trade languages” with terms borrowed from multiple languages to ensure mutual comprehension, a process similar to the adoption of a lingua franca among traders in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea during the Middle Ages. By the 1580s, the Innu and Mi’kmaq—not to mention the Inuit further north—had extrapolated from this tendency by adapting European words into their speech. (It was especially common to borrow from the Basques, whose language is the origin of some words that survive in Indigenous languages to this day.)

The ingredients were there for a new supply chain to emerge. And the only thing preventing large-scale exploitation of this market was inertia. If you were an established European fur merchant, why risk investing in an enterprise you’d have to build from the ground up, when there were safe, steady profits to be had in Russia?

It took a major disruption of the Russian fur trade for Europe to turn its attention to Canada. Specifically: In 1581, during the Livonian War, a Swedish army conquered Narva from the Russians. Deprived of a Russian port from which to import its beaver pelts, the European fashion industry frantically searched for an alternative.

The first to seize the opportunity were French merchants operating out of Normandy. Fishermen from the Norman port of Dieppe had been making the annual trip to Canada for years. But now the merchants of nearby Rouen also got interested. Crucially, Rouen sat on the Seine, a few miles upriver from the coast, on the main route to Paris, home to one of the densest concentrations of hatters in Europe. In the 1570s, groups of Norman merchants had started organizing the first voyages dedicated solely to the fur trade, experiments that took off once the Russian trade was interrupted.

The Norman traders focused on the area around Cape Breton, which now comprises the eastern part of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, mostly because that was the region that Dieppe fishermen had been working for decades. The fur traders relied on the local knowledge of men who’d been going there their whole adult lives.

At Cape Breton, the Normans traded with the Mi’kmaq, who had demonstrated an enthusiasm for trade as far back as Cartier’s first voyage five decades earlier. They quickly adapted to the arrival of large-scale buyers, and began gearing their economy toward trapping at the expense of fishing. Trade presented a more efficient way to acquire food, and the Mi’kmaq diet shifted toward biscuits and the dried peas the French brought with them. Even more prized were iron weapons and tools. Very quickly, the Mi’kmaq developed a significant military advantage over their local rivals.

Other Europeans moved to mimic the Normans. The English, who’d jealously guarded their fishing grounds off the Atlantic side of Newfoundland, sought to establish trade with the Beothuk who lived on the island. (As discussed back in the fourth instalment of this series, the Beothuk had learned to fear Europeans, having had a brutal run-in with Portugal’s Gaspar Corte-Real). Blazing the trail for the English was Humphrey Gilbert, a well-connected gentleman out of Devon with a history of Atlantic adventures.

Gilbert was the half-brother of the romantic adventurer Walter Raleigh, who was planning a colonial project in Virginia around the same time. Being a bit of a dreamer himself, Gilbert had gambled big on Martin Frobisher’s expeditions (which we covered in the last instalment), and (like many other people) had lost a lot of money. But that didn’t deter Gilbert from trying again.

He had a novel strategy for raising money for his new project—a real challenge after Frobisher’s disaster had soured English investors on Canadian enterprises. Gilbert turned to England’s Catholic population, an insecure minority in the kingdom who’d come under political suspicion amid the hostility between the Protestant Queen Elizabeth and his most Catholic Majesty, King Philip II of Spain. (The Spanish Armada was just a few years away.)

The idea was for the Newfoundland colony to be a place where English Catholics could practice their faith openly, without fear of reprisals from the state or their neighbours—a sort of Catholic version of the Puritan migration that would later flow to Massachusetts. The fund-raising campaign worked, and by 1583 Gilbert had a slew of Catholic investors lined up.

But politics intervened. England’s Privy Council decreed that any Catholic seeking to re-locate to the New World would have to pay heavy fines first. Meanwhile, the self-proclaimed protector of England’s Catholics, Philip II of Spain, also discouraged any colonization effort, which he deemed a violation of Spanish claims to the Americas. Moreover, Philip felt that English Catholics would be more useful to him in England, where they could act as a fifth column in the event of a Spanish invasion. As a result, most of Gilbert’s Catholic investors backed out, though it would not be the last time that England’s Catholics looked for salvation in Newfoundland.

As a fallback, Gilbert assembled a crew out of criminals and opportunistic rogues (alongside his half-brother Walter Raleigh) and set out for Newfoundland in the summer of 1583, undeterred. The crossing took longer than expected, and Raleigh’s ship had to turn back home due to lack of supplies. But in August, Gilbert arrived at St. John’s, which had become the home base for the English fishing fleet.

There, Gilbert encountered his first obstacle: English fishermen weren’t inclined to respect Gilbert’s claims of authority over them, notwithstanding the official documents that had been given to him by the Queen. Mostly, this was because one of Gilbert’s captains was a notorious pirate who’d spent the previous year raiding ships in the area. It didn’t help that Gilbert attempted to levy taxes from all ships plying the nearby waters.

Eventually, the fishermen bent to the power of the state that was backing Gilbert’s enterprise. But they did so reluctantly, and provided no support for a permanent settlement. Within a few weeks, Gilbert determined that he didn’t have the supplies necessary to establish a colony. His men seemed more interested in pillaging fishing vessels than building a settlement (or, for that matter, following Gilbert’s orders). By the end of August, he decided to head home.

The return trip was an even worse disaster. Of the three ships remaining in his fleet, one ran aground in the treacherous waters off Sable Island, off the coast of Nova Scotia. A second went down in the middle of the Atlantic, with the loss of all souls (including Gilbert himself). The only ship to make it home was the Golden Hind—the ship Francis Drake had used to circumnavigate the globe three years earlier.

Gilbert’s voyage was not quite as financially costly as Frobisher’s misadventures had been, but it was a fiasco all the same. English settlement in the region would have to wait.

Even if Gilbert had been successful, however, Newfoundland was not an ideal place to engage in trade. The Beothuk who lived in the interior of the island were far less interested in interacting with Europeans than the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia. As noted above, contact at the beginning of the sixteenth century had been brutal, and numerous attempts to establish relations with the Beothuk in the future would prove futile.

The one group of Europeans who did manage to emulate, and even surpass the Normans were the ubiquitous Basques. Part of this had to do with developing trends in whaling. After decades of good hunting, the main Basque whaling grounds in the Strait of Belle Isle, which separates the Labrador Peninsula from Newfoundland, were becoming less bountiful. It’s possible that the whalers were too efficient for their own good, depleting the local stock. But a change in climate might have been the real culprit. The earth was entering a period of global cooling, and the whales may have been adapting their habits to the changing environment.

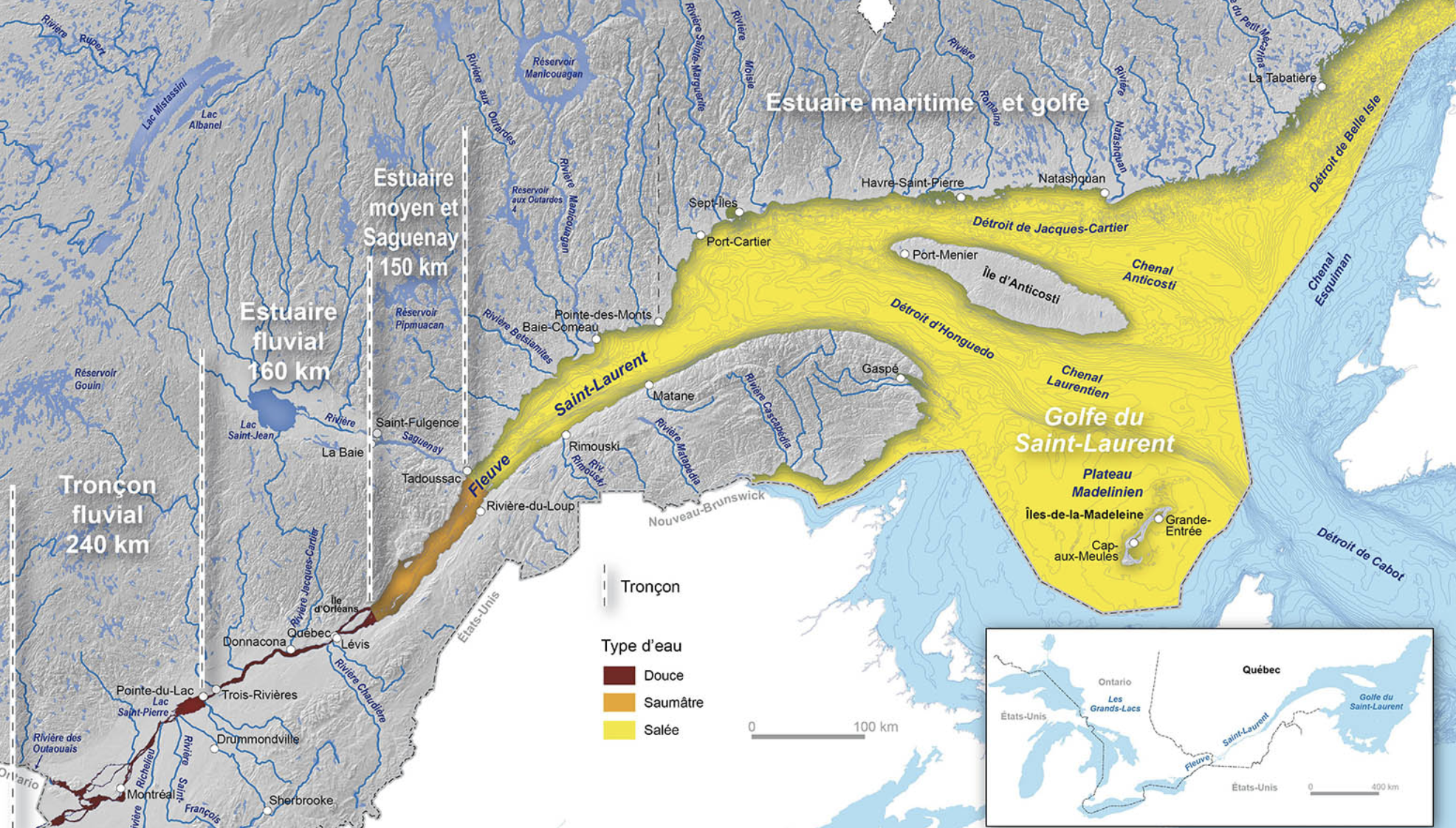

Either way, by the 1580s, the Basques were responding to the decline in the annual whale hunt by moving further afield. Many Basques pushed into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in search of whales, some even into the mouth of the river itself. The largest of their new whaling stations was at the (appropriately named) Île aux Basques, an island about 200 kilometers northeast of where the river narrowed decisively at Stadacona—near (what would become) the town of Rivière-du-Loup. The channel there was 30 kilometers wide and played host to an ample supply of whales.

But more importantly, the Basques had managed to position their whaling station right next to the central hub of an expansive, continental trade network. Across the St. Lawrence from Île aux Basques sat Tadoussac, long used as a meeting place for various Indigenous peoples. The site was ideally suited for the coming together of nations for a few reasons. First, it sat on a kind of borderline. To the south and west lay land suitable for the corn-growing societies of the Iroquoian confederacies. And to the north lay the rugged Canadian Shield, populated by the hunting nations of the Algonquin speakers.

Tadoussac was a natural place for cultural and economic exchange between these two social models, being surrounded by the natural highways that made long-distance travel possible in the massive interior of eastern Canada. As the glaciers slowly retreated thousands of years ago, they left a complex network of lakes and rivers in their wake. The mighty St. Lawrence River was the great superhighway, cutting through the land for more than 500 kilometers between Stadacona and Lake Ontario. But the great hinterland to the north was also drawn into the network by a web of smaller tributaries that fed into each other, and, eventually, the St. Lawrence.

Extending west was the Saguenay River, the terminus of a series of waterways that extended northwest out to Hudson Bay, around 800 kilometers away. (The French name for the river derived from the fictional, extravagantly wealthy Kingdom of Saguenay, which Indigenous people had convinced Cartier lay over the horizon.) For the Europeans camped at Île aux Basques, that meant access to a potential flow of fur that dwarfed anything the Mi’kmaq were capable of producing from their territory in Nova Scotia. Here, finally, was the commodity that would make European intervention in mainland Canada financially viable.

By the 1580s, the Basques had four whaling stations on Ile aux Basques, and just like in the Strait of Belle Isle, there is evidence that they employed Indigenous labour on these sites. These working relationships likely facilitated trade, and the Basques quickly realized the potential of the Saguenay River.

The Innu, who inhabited the lands to the northeast, were just as quick to see the benefits of controlling the spigot for a whole continent’s worth of fur. If the Europeans had learned a great deal about Indigenous trading practices over the past century, the Innu had likewise become avid students of European commerce. Most of all, they understood the value of their status as middlemen situated between source and buyer. In the following decades, the Innu would pursue a dogged policy of maintaining this privileged position. They politely, but firmly, refused to guide adventurous Europeans up the Saguenay (thus sustaining myths about what lay beyond). At the same time, they spread tales of European viciousness and cruelty into northern Indigenous communities: Better for you to just send your furs downriver and let the Innu handle the face-to-face trade with these dangerous foreigners.

During this period, some of the Basques dropped whaling entirely and switched to exclusively trading in fur. Among the most prominent was Martin de Hoyarçabal (often rendered as Martin Oihartzabal), a French mariner based in the Basque port of Saint-Jean-de-Luz. In the winter of 1586-87, he became the first European fur trader we know of who stayed in the St. Lawrence all year round. The evidence of the business he conducted is scant, but records in Saint-Jean-de-Luz indicate that Hoyarçabal habitually cleaned out the port’s supply of copper kettles (very popular items among the Innu). His ships often carried iron axes, swords and knives as well, which were plentiful enough in Basque country as it was one of the leading metal-working regions of Europe.

It didn’t take long for other Europeans to see the commercial opportunity the Basques were exploiting. And in the absence of any kind of state-backed authority, competition often turned violent. In the summer of 1587, four ships out of St. Malo were captured and burned by Basque rivals.

Such lawlessness was not conducive to commerce. But Spain was at war with England, and its naval resources were stretched too thin for ships to be sent off to Canada. Meanwhile, France was still embroiled in its disastrous Wars of Religion. And so while the fur trade was certainly profitable, it was also dangerous business.

In these early days, in fact, most attempts to bring order to the fur trade came from the Innu rather than the Europeans. In an effort to secure their role amid an uncomfortably uncertain state of affairs, multiple Innu leaders sent their sons to Europe to cement relationships with their trading partners. Unlike the abductions engineered by Cartier and Frobisher, these quasi-trade delegations were voluntary. In fact, they were a key part of traditional Indigenous trading practices. Until an alliance was confirmed through mutual displays of hospitality, such bonds were seen as easily broken. This was part of the reason why the Stadaconans had been so offended by Cartier’s desire to press on to Hochelaga rather than staying in their village. Playing host to a visitor, especially over an entire winter, was an extremely meaningful step in forging bonds in the Indigenous world.

But despite the obvious commercial benefits of the Canadian fur trade, and Innu attempts to craft more formal trade arrangements, the boom of the 1580s proved to be short-lived. The lack of law and order in the Gulf of St. Lawrence discouraged all but the most adventurous of investors. And at the end of the decade, the enterprising Dutch established a new access point for Russian fur—the arctic port of Archangel. The fur trade in the St. Lawrence region slowed, but it did not disappear. By now, it had become a permanent feature of the regional economy, with dedicated fur traders dropping anchor next to fishermen and whalers.

For the Europeans, the fundamental dilemma was as follows. In order to provide the stability necessary to encourage large-scale trading overall, someone would have to establish a permanent colony in the area, run by individuals capable of enforcing the law—a project that would require massive up-front costs. But each individual trader had a short-term incentive to oppose such a scheme. As long as you weren’t the one losing your cargo to raiders, the laissez-faire status quo was better than a situation in which government agents were taking protection money from you in the form of taxes.

At this point, I will turn to the second, parallel story that I’ll be covering in this instalment, involving the other end of the St. Lawrence, where the Iroquoian-speaking confederations had been thrown into flux.

When Jacques Cartier’s nephew, Jacques Noël, followed in his uncle’s footsteps four decades later and sailed up the St. Lawrence in 1585, he found that the villages of Stadacona and Hochelaga had disappeared. Where once there had been thriving communities, now the river was an abandoned wilderness. As noted above, a popular inference is that the introduction of European trade goods had revolutionized the economic and political relationships between the Indigenous nations of the region. In the vicious competition for access to European goods (especially iron weapons), the Iroquoian villages along the St. Lawrence had been destroyed by more powerful rivals in the Great Lakes.

But the timeline that archaeologists have subsequently constructed casts serious doubts on this theory. We know that by the time Europeans started re-tracing Cartier’s steps up-river in the 1580s, Stadacona and Hochelaga had been abandoned for quite some time. And yet there is scant evidence that European trade goods made their way to the Wendat or the Iroquois in significant amounts before the fur boom of the 1580s.

In other words, when the Hochelagans and Stadaconans were dispersed (probably some time in the 1560s or 1570s), the flow of Europeans goods up the St. Lawrence was, at best, a trickle. It doesn’t seem likely that the wholesale destruction of communities in the region would have been sparked by such minor commercial activity.

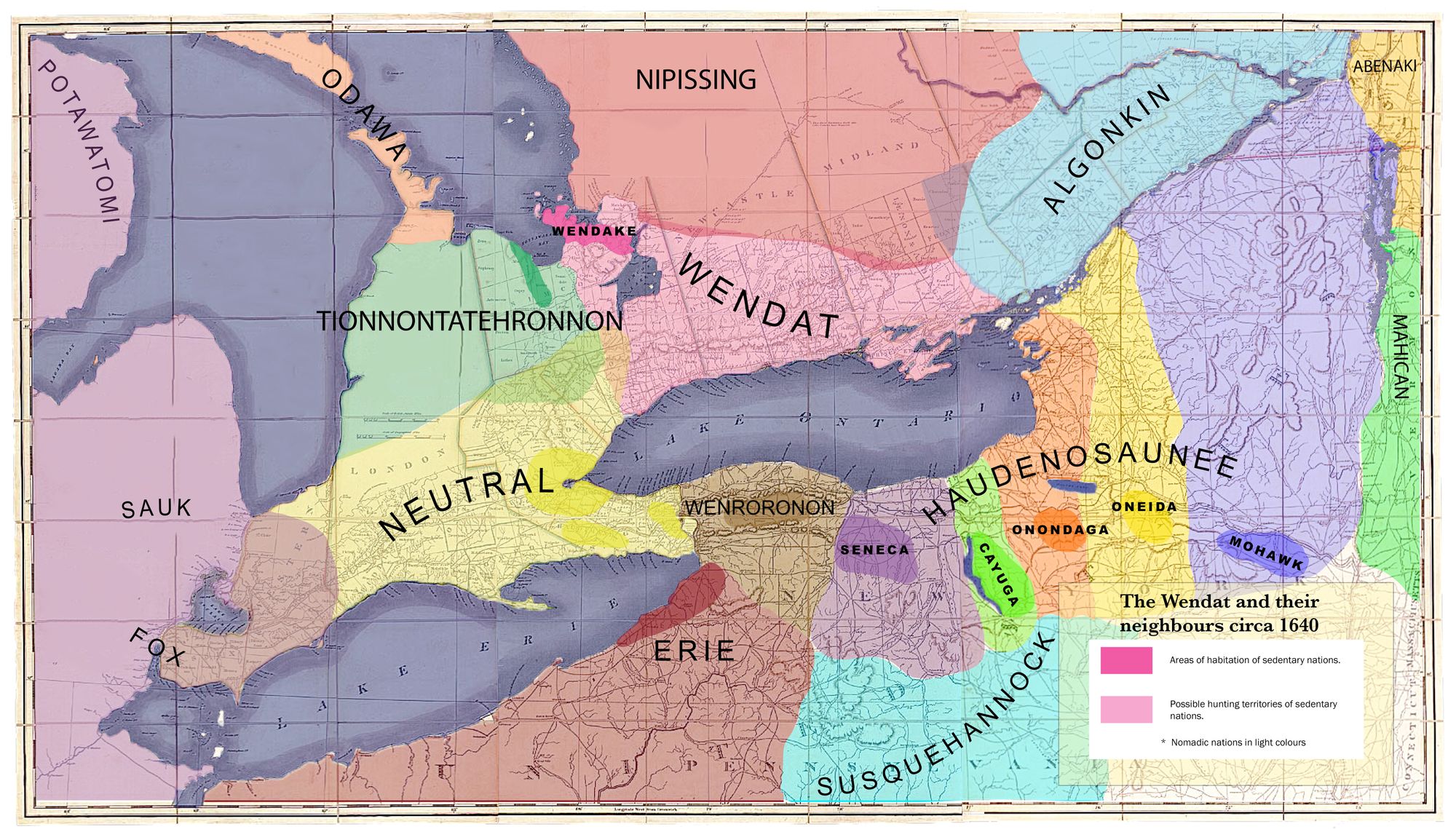

Over the past few generations, historians have pursued an alternative explanation that focuses on pre-existing tensions within the Iroquoian-speaking world. As discussed in the third instalment, the upper St. Lawrence and Great Lakes region was populated by Iroquoian-speaking corn farmers. Over the course of the fifteenth century, these various societies underwent a process of consolidation. Villages grew in size, and then allied with one another, largely in pursuit of collective security. With women dominating the agricultural work that drove the economy, men increasingly built their identities around warfare. And the greater concentrations of people in villages, along with the political ties between those villages, meant that the Iroquoians could wage a more organized form of warfare than their hunter/gatherer neighbours.

The highest level of political organization was the Confederacy, a cross between a mutual defensive pact and a dispute-resolution forum. Several of these Confederacies dotted the landscape around the Great Lakes, each with its own distinct characteristics. The two most important were the Wendat Confederacy, nestled between Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe, and the Five Nations Iroquois Confederacy, hugging the south shore of Lake Ontario (in modern New York State). These were the two superpowers of the Iroquoian world.

The Iroquoians who are the focus of our mystery, the St. Lawrence villagers of Stadacona and Hochelaga, were on the periphery of this world. The easternmost nation of the Iroquois Confederacy, the Mohawk, sat nearby, on the south bank of the St. Lawrence. The Wendat were further removed, with their homeland sitting more than 500 kilometers from Hochelaga. But Wendat influence spread through a web of trade routes among the Algonquin speakers of the north. And one of those main routes, through the Ottawa Valley, linked up with the St. Lawrence at Hochelaga.

In other words, both the Iroquois and the Wendat had an interest in the Upper St. Lawrence. That interest could take many forms. And due to the structure of sixteenth-century Iroquoian societies, one of those forms, inevitably, was war. Demonstrating prestige in war was one of the main ways men established their status in the community. (A second way was through liberal generosity, best accomplished by distributing the spoils of war among your neighbours.)

When Jacques Cartier visited Stadacona, he noted that the village leaders talked of a perpetual war to their west. This was not a European-style war of conquest, but a kind of continuous campaign of low-level raids and counter-raids, fueled by social pressures and a never-ending cycle of revenge for past violence. What, then, elevated this kind of war to a scale capable of dispersing entire villages?

It’s possible that a variety of factors severely weakened the St. Lawrence villages in the middle of the sixteenth century, leaving them especially vulnerable to attacks from their more powerful neighbours.

Lying on the margins of the corn-friendly Great Lakes/St. Lawrence region, Stadacona and its upriver neighbours stood to suffer the most from a downturn in climate. Marginal land could quickly become insufficient to support the existing level of population, forcing disruptive adaptations. And there is some evidence that in the mid-to-late sixteenth century, there was significant cooling in this region.

And while there’s not much evidence of European goods making their way up the St. Lawrence before 1580, they were becoming common among the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia. And European iron (especially in the form of weapons) likely altered the balance of power in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Remember that, as part of their mixed economy, the Stadaconans made an annual trip to the mouth of the river, where they competed with Algonquin speakers such as the Mi’kmaq for the best fishing grounds. It’s possible that the Mi’kmaq, increasingly better armed with iron axes and other weapons, exerted greater control over resources in the area. The result would have been both a loss of manpower and restricted access to resources.

Finally, it’s possible that European diseases may have ravaged the St. Lawrence villages, while leaving the Iroquoians deeper inland relatively unscathed. During Cartier’s attempt at colonization in the 1540s, the French observed an infectious disease running through Stadacona. Whatever the disease was, it was not as devastating as the epidemics that would later tear through the Indigenous world in the seventeenth century. Nor did European visitors note any diseases among the coastal populations in subsequent years. But it is plausible that European-borne diseases were already spreading in the region. If so, the St. Lawrence Iroquoians would have been more likely to be affected than the Confederacies that lay deeper within the continental interior.

If the Stadaconans and Hochelagans had their economic base undermined by a changing climate and increased competition from the Maritimes, and their manpower depleted by disease, then they may have lost confidence in the security of their villages. If they could not adequately protect themselves against raids from their neighbours, their only option would be to abandon their settlements. Some may have split into smaller groups and adopted the hunting and fishing techniques of their Algonquin-speaking neighbours. Others could have taken advantage of kinship ties with neighbouring bands and joined new groups. Still others may have been more forcibly assimilated by Wendat or Iroquois warriors.

We simply will never have definitive evidence for the fate of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. But many years later, Europeans did witness just such a dispersal of an indigenous society, when the French-allied Wendat Confederacy collapsed in the mid-seventeenth century. The strategies adopted by those refugees offer a plausible template for how the Stadaconans and Hochelagans may have reacted to their own changing circumstances many decades earlier.

Archaeologist Joyce Wright argues that a significant portion of the St. Lawrence refugees ended up in the Wendat Confederacy. In the second half of the sixteenth century, Hochelagan and Stadaconan pottery styles start appearing in Wendat settlements in large numbers. Wright speculates that this was the result of an organized migration. She further suggests that this movement of people was the result of war.

All of the St. Lawrence-style pottery Wright discovered among the Wendat was intended for food storage—objects created by women. She could find no evidence of St. Lawrence-style clay tobacco pipes, objects exclusively crafted by men. Wright’s tentative conclusion is that the Wendat conquered the St. Lawrence villages, killing or dispersing the men, and adopting the women and children.

Other scholars see the Iroquois Confederacy as the more likely culprit. The compelling evidence here is not so much archaeological as deductive. Conflict between the Iroquois and the St. Lawrence villages makes more sense than a Wendat conquest, the argument goes. The Mohawk were virtual neighbours to the Hochelagans, and the hinterland along the river was some of the best hunting territory in the region. Competition may have led to violence.

Also, the Iroquois were far more dependent on hunting to supplement their agriculture than the Wendat. The Wendat traded their surplus corn with Algonquin-speaking hunters, getting meat and furs in exchange. The Iroquois, on the other hand, were surrounded by fellow farmers, and so had fewer opportunities for mutually beneficial trade. Securing good hunting grounds was a more existential problem for the Iroquois than for the Wendat.

From this perspective, the newcomers to the Wendat Confederacy may have been more like refugees being granted asylum, rather than prisoners of war.

Another answer to the mystery of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians has emerged from the study of the Algonquin-speaking nations that lived to the north of the river. In particular, there is evidence of Iroquoian cultural influences on the Algonquin speakers who lived in the valley of the Ottawa River—the waterway that connected the Wendat to the St. Lawrence at Hochelaga. It is possible that this was the result of generations of trade with the Wendat Confederacy. But it is also plausible that a sizeable group of Hochelagans and Stadaconans abandoned their villages and migrated up the Ottawa Valley in the sixteenth century, eventually adopting the economic and social practices of the Algonquin speakers.

Whatever happened to the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, their absence would have a profound effect on Canadian history. After the disappearance of the river villages, the upper St. Lawrence became a kind of no-man’s land. Rather than supporting permanent settlements, the region played host to rival hunting parties and raiding bands. Algonquin speakers from the Ottawa Valley, Innu from Tadoussac, and Mohawk from the south, all criss-crossed the terrain.

Which provided an unexpected opportunity for the Europeans who were suddenly taking a renewed interest in the St. Lawrence River at the end of the 16th century. Here was fertile land, well situated on one of the world’s great waterways, which hosted multiple powers locked in violent competition.

There was an opportunity here for a relatively small group of outsiders to wield a tremendous influence. If someone could settle the St. Lawrence, then act as a broker, subtly influencing the balance of power in the region, a colonial empire might be built inexpensively through diplomacy, rather than conquest.

Here is where our two stories intertwine. The common theme running through both is opportunity. The fur trade held out the possibility of immense profits to whoever could establish a functioning market, while the unoccupied St. Lawrence offered a geopolitical window of opportunity for anyone shrewd enough to fill the local power vacuum for their own purposes.