Review

The Eyes of the Storm

A historic diary in pictures, which just happens to belong to Sir Paul McCartney.

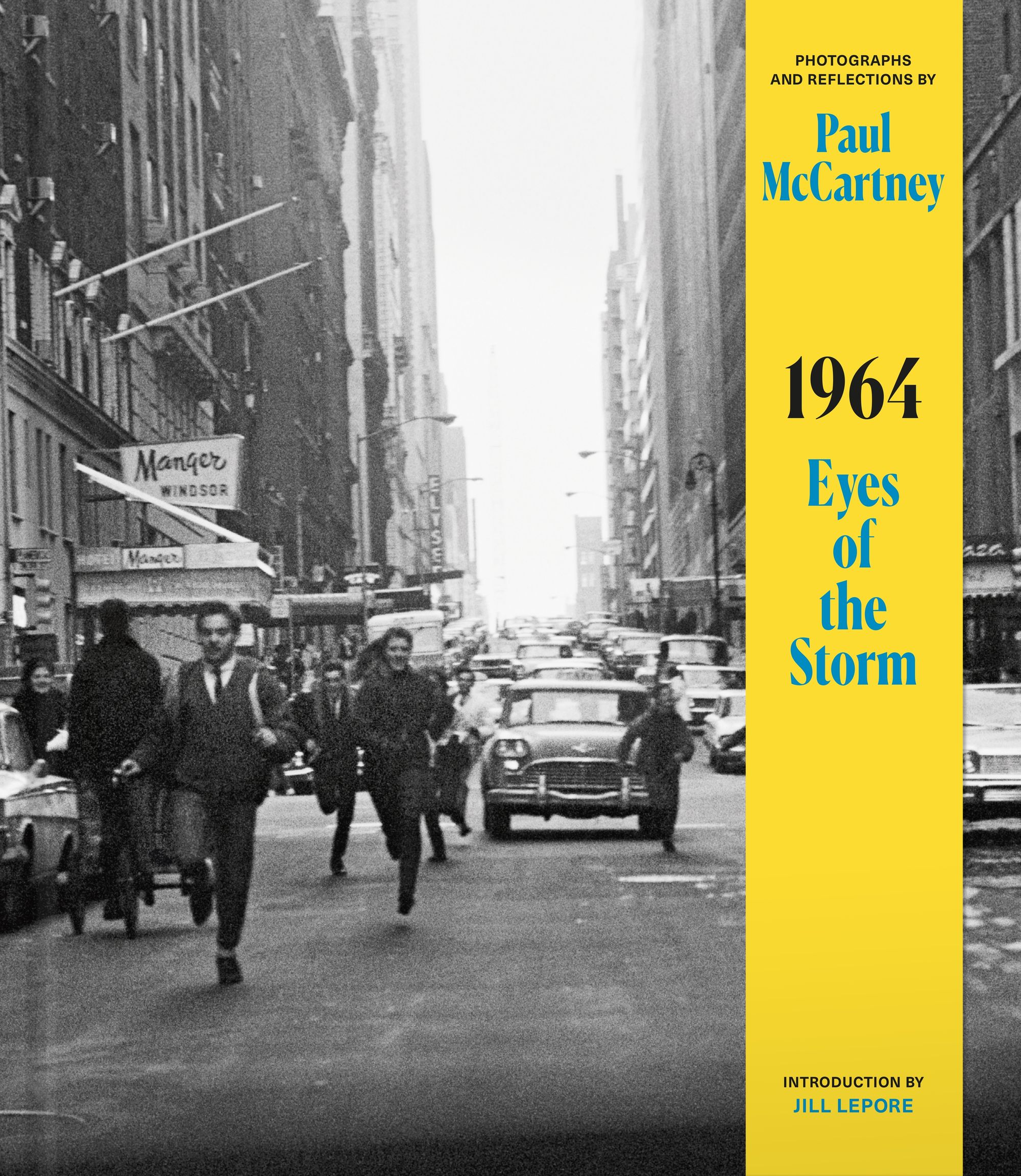

A review of 1964: Eyes of the Storm by Paul McCartney (Allen Lane, June 2023).

Paul McCartney Photographs 1963–64: Eyes of the Storm

Exhibition. National Portrait Gallery, London (28 June–1 October 2023).

More times than he can count, Paul McCartney has been asked to write an autobiography. Time after time, he has declined. The iconic Beatle has never kept a diary or a notebook either—“what I do have are my songs,” he has argued, “hundreds of them, which, I’ve learned, serve much the same purpose”: candid, intimate glimpses of singular moments in time—much like the thousands of photographs he has taken over the years, which are personal, uncontrived, and uniquely telling.

Paul McCartney has been taking pictures all his life: from his Liverpool childhood days, when he used his parents’ Kodak Brownie, to the stellar heights of Beatlemania and the music-infused decades that followed.

Eyes of the Storm is a new book and National Portrait Gallery exhibition of photographs taken by the wide-eyed, young McCartney over four momentous months in The Beatles’ lives. Recently discovered in McCartney’s archives, they are an intimate, hitherto-unseen record of the band’s journey through five cities and on one milestone transatlantic flight, at the end of which, Paul, John, George, and Ringo became the most famous musicians on the planet—“more popular than Jesus.”

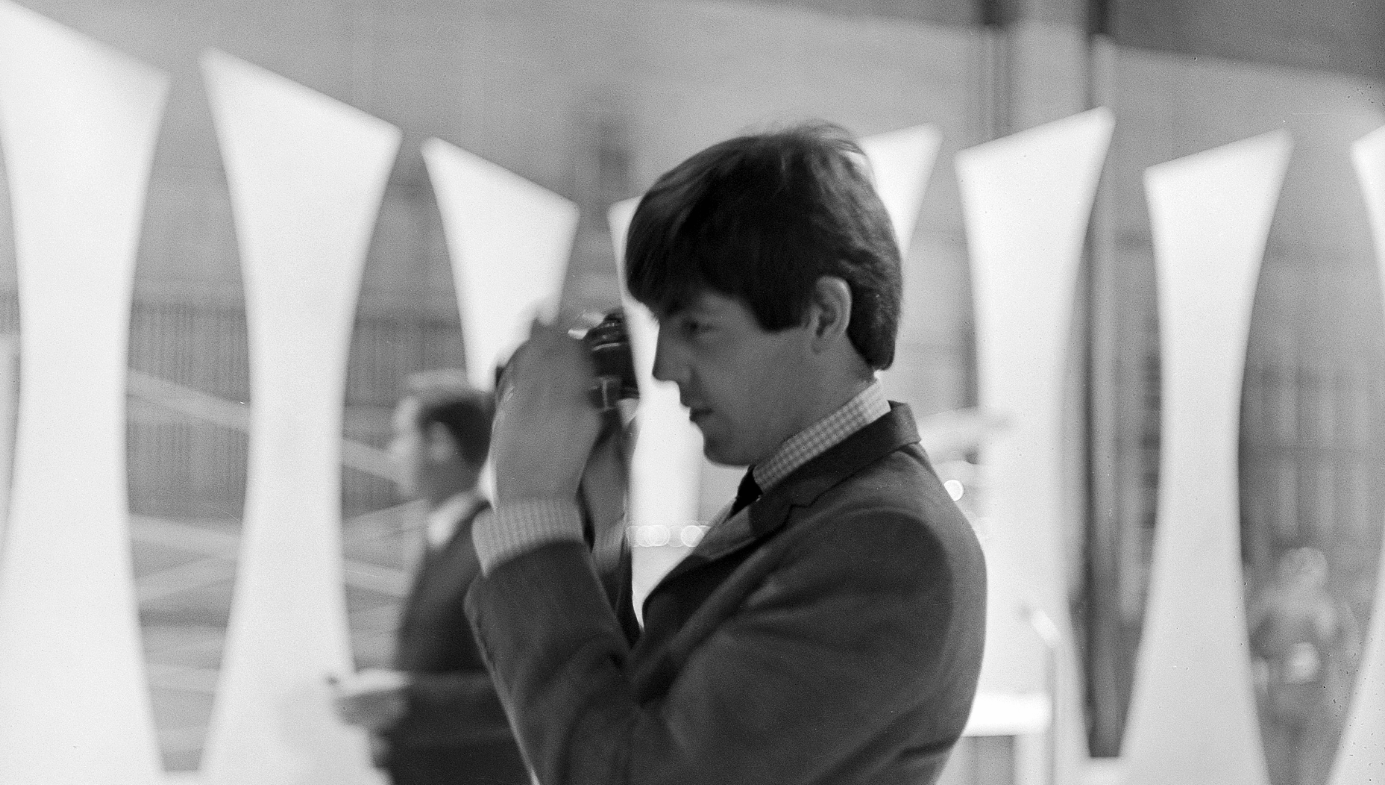

Starting in November 1963, the boys travelled from Liverpool to London, Paris, New York, Washington, and Miami, and each step of their journey was captured on McCartney’s Pentax SLR. “From the moment he acquired a camera in the autumn of 1963,” explained the exhibition’s curator Rosie Broadley, “McCartney documented his life with The Beatles”: with portraits of George, John, and Ringo; family members; screaming fans; press photographers; street scenes; cityscapes; and the band’s entourage, “an extended cast of characters usually overlooked,” including roadies Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall; chauffeur Bill Corbett, who drove their Austin Princess; publicist Tony Barrow; and Freda Kelly, who ran the fan club.

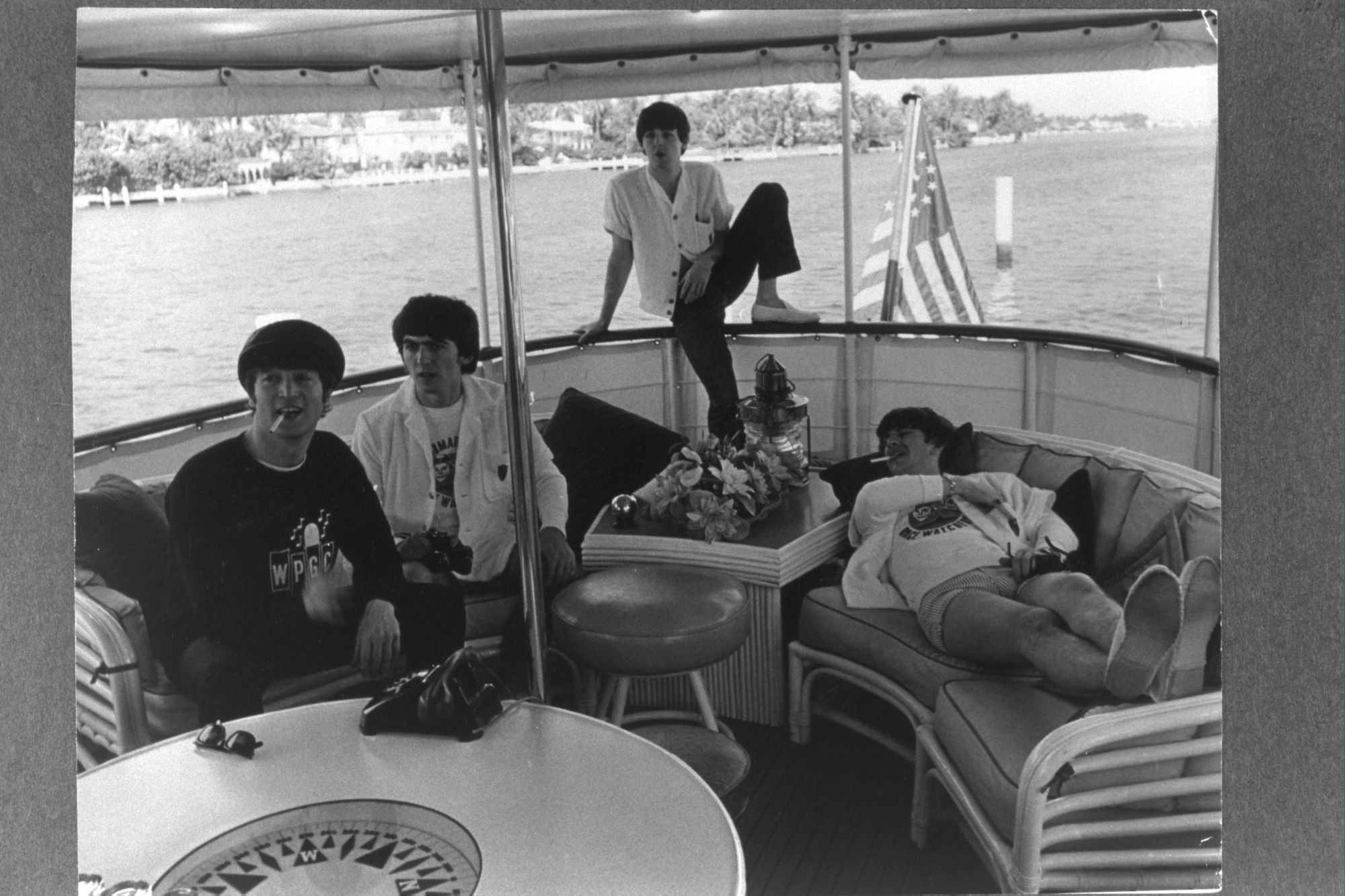

“Everywhere I went, I just took pictures,” McCartney told Broadley: on stage, backstage, in hotel rooms, on board a plane, from a moving car and a speeding train—recording intimate moments that only a Beatle could capture, from a relaxed Brian Epstein laughing, and Ringo napping in a chair, to an in-car shot of John wearing a pair of thick glasses he only wore in private—“as soon as girls were around he took them off,” explained McCartney. “Press photographers couldn’t get there—or if they did, John would start hamming it up, but because it was me he didn’t care.”

There are on- and off-stage photos of fellow performers; portraits of George’s sister and his parents, Louise and Harry; of Cynthia Lennon; Judy Lockhart Smith of Parlophone Records, who later became George Martin’s wife; Juke Box Jury presenter David Jacobs; and many other characters caught up in the Beatlemania storm. In London in 1963, McCartney captured sensual black-and-white portraits of then girlfriend Jane Asher, in whose family home he was staying. There is also the distinctively English view from the back of the Ashers’ house and a photo of Jane’s brother Peter, who inspired the song “A World Without Love,” which would go on to replace “Can’t Buy Me Love” at Number 1 in the UK charts. “Not only did the Ashers give me a home away from home,” writes McCartney in the book, “but it was full of interesting people and conversations.” There was a piano in McCartney’s bedroom and another in the living room, where Jane’s mother taught piano. “One of her students had been a young gentleman named George Martin,” who, some years later, would become The Beatles’ legendary producer.

“There is a sense of intimacy and trust in these photos,” said National Portrait Gallery director Nicholas Cullinan, “a real tenderness and vulnerability. The informality and intimacy of these portraits is what makes then so unique.” There are off-guard, unaffected shots of what McCartney calls “a tight-knit group,” immersive photographs “only one of us would have been able to get”: the boys in their dressing rooms getting ready to go on stage at Liverpool’s Finsbury Park Astoria; John in front of a mirror; an exhausted George sleeping on the plane to New York; Ringo in make-up; John with his eyes fixed on a lucky female fan, who had been allowed into their dressing room; George curled up in a chair, deep in thought; John “remaining serene” as commotion ensues around him—and more.

Interspersed throughout are shots of workmen encountered along the way. On route to Washington, from a moving train, McCartney photographed a worker, spade in hand; in New York, he photographed on-duty policemen who were keeping the peace; in Miami, he photographed an airport worker playing air guitar, clearly thrilled to have The Beatle’s lens focusing on him. “Anyone else might have thought, ‘Oh well, there’s just a guy who’s come to fix the aeroplane or get it ready for take-off,’” McCartney told Broadley. “[But] being from the working classes, I'd relate to them. My family and I did that, we all did menial work, so I know a bit about what’s inside the heads of those people, because I was one, too”—a point he later raised with Stanley Tucci on the National Portrait Gallery’s all-too-brief Eyes of the Storm podcast. McCartney resented the kind of middle- and upper-class condescension towards working-class folk depicted in “that Monty Python sketch.” He talked about “very clever people” in his family who “never made it—it was ‘just an insurance clerk’ or whatever, but they were very clever and had a lot of knowledge.”

But it wasn’t just workmen who greeted McCartney’s camera with a smile—countless press photographers are seen playfully gesturing, smiling widely as they catch sight of McCartney’s camera pointing at them. “By 1963, The Beatles were facing cameras everywhere they looked,” explained Broadley, “and at that point, the camera itself becomes a motif in McCartney's photographs. In Paris and New York, he turns his lens on the photographers themselves, crowded into the foreground and jostling for a shot. Despite the apparent intensity of these situations, when all lenses are turned on McCartney, there is also playfulness—the photographers seem delighted that McCartney has noticed them,” and is taking their picture.

“This would not happen today,” Tucci told McCartney, referring to one photographer, clearly “delighted to have the tables turned on him,” his arms spread wide and a huge smile on his face. “Press were lovable Rogues,” replied McCartney. “Now they’re just rogues.”

America: When Everything Changed

“The photographs derive from a three month period,” NPG curator Rosie Broadley told Quillette, “from the moment Paul McCartney acquired a new Pentax 35mm camera to the band’s last few days in America. They went from UK Beatlemania to becoming global superstars. It was a real historic turning point for them, for music, and for the idea of fame.”

In Liverpool and London, they performed in venues that included the Finsbury Park Astoria and the Palladium—“these are all interiors, dressing rooms in these little cinemas. You can see the kind of kitchen sink aesthetic in these photographs.” But then they go to Paris, where the mood is quite different. McCartney turns to cool Paris street scenes, elegantly dressed locals, and posed shots of the boys. It is while in Paris that they get a telegram saying that they have reached Number 1 in the US with “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and greenlighting the yearned-for trip to the US. “I knew that we would only go to America once we had a Number 1,” explains McCartney, “I’ve seen it before, bands going there and just fizzling out.”

In February 1964, the four kids from Liverpool departed from Heathrow to the sound of thousands of fans’ excited screams. In New York, more ecstatic, screaming fans awaited, along with hitherto-unseen hysteria. The Beatlemania storm was in full force.

“We have a room at the exhibition that is devoted to their arrival,” said Broadley. “Thousands and thousands of people welcomed them. That has never happened before.” From the back of the band’s car, McCartney photographed the awe-struck crowds and the local police, against a background of distinctive high-rise New York architecture.

“We all know what Beatlemania looked and sounded like from the outside,” commented Cullinan, “Through these shots, we know what it looked and felt like for the four pairs of eyes that lived and witnessed it first-hand.” It was on New York’s West 58th Street that McCartney captured an epic image of the fans excitedly chasing the band’s car. The city’s iconic skyscrapers frame the striking shot. “The crowds chasing us in A Hard Day’s Night,’” notes McCartney, “were based on moments like this.”

At John F. Kennedy Airport, they gave the famously upbeat press conference that has become part of Western cultural folklore. The National Portrait Gallery exhibition wisely plays the playful exchange with the press on a loop. It is an arresting moment, as you gaze at the somewhat childish innocence that is about to be lost, the lighthearted, thoroughly English boys, in their suits and ties, with their thick “it’s not English, it’s Liverpudlian” accent, using humor as they face the brazen questions of the New York press. The four wisecracking guys had no idea what was unfolding. The historic, unprecedented magnitude of the brewing Beatlemania storm could not have been foreseen by anyone. Two days later, they played on The Ed Sullivan Show, watched by 73 million viewers, and then gave their first US concert at the Washington Coliseum. Back in New York, they gave two shows at Carnegie Hall before flying to Florida for another appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, watched by 70 million viewers. Almost overnight, the four kids from Liverpool became global icons—unknown to themselves, the Beatles had invented fame.

“You all had the greatest sense of humour—a great sense of irony, which has disappeared a little bit in our world,” Tucci told McCartney. But it is not just the sense of irony that has been lost—it is the positive attitudes of the journalists and press photographers, the vinyl album covers that were works of art, the boys’ innocence and—most notably—the photographic medium itself, which has been transformed. These were different times.

“It was a different era for photography,” explained McCartney. “There was none of that ‘it’s in the back of the camera,’ where you can instantly see what you’ve taken, which I think was actually better because now it’s just too easy.”

Analogue photography was a laborious process. There were no instant images to look at. “You had just 36 shots captured on a negative that had to be sent for processing,” added McCartney. “You had no idea what you actually captured” until days later, when the negative and the contact sheet came back. “It made you really think about it,” replied Tucci. “Do I like that image? Why do I like that take? And then, how does that fit together with all the other pieces? Just like this exhibit—how do all these pieces work together? And it’s something that’s disappeared now.”

So divorced is today’s photography from the 1964 process that the NPG has created a video for visitors, demonstrating the time-consuming, skilled art of pre-digital photography. “There are contact sheets all around the exhibition and in the book,” said Broadley. “We had to explain to people what these are. In 1964, there were no image previews or instant results. In fact, it’s worth pointing out that none of the photographs actually existed when we were looking at the images because they were only preserved as negatives and contacts. One of the most magical parts was when we had the works printed—it was the first time that not only we had seen them large, but it was actually the first time that Paul McCartney himself had seen these photographs as prints.”

This night-and-day contrast between the photography of the 1960s and today’s photography brings to light the significance and uniqueness of these shots. “McCartney was able to take photographs that were genuinely snapshots,” commented critical theorist and fellow Liverpudlian Paul A. Taylor, “whereas we now live in a time where everything is being videoed. They are not genuine snapshots because they’re not a unique moment in time—they are a continual, endless tsunami of images. In The Beatles’ time, images just weren’t so prevalent.”

The Beatles’ first visit to the US took place when the nation was still mourning the assassination of President John F. Kennedy the previous November. “It was a few months after that that we came to America, and people were feeling it,” reflected McCartney. “Without meaning to, we kind of lifted a lot of people out of the doldrums. They were saying, ‘Oh, there’s something to smile about and to dance for,’ because the mood of the country was quite sombre.” Historian Jill Lepore’s introduction to the Eyes of the Storm book also touches on the group’s impact: “Commentators often suggest that, for many, particularly the young, the Beatles’ performances reignited the sense of excitement and possibility that momentarily faded in the wake of the assassination and helped pave the way for the revolutionary social changes to come later in the decade.” Several years later, the boys would refuse to play before a segregated audience and McCartney would write the iconic “Blackbird.”

Blue Skies and Sapphire Seas

In Miami, the last stop on The Beatles’ historic journey, McCartney captured some of the most memorable shots. At the airport, he captured an epic image of countless fans huddled together to greet the band—it’s Beatlemania Bedlam in all its glory, with beauty queens lined up in the center, people hanging from staircases and rooftops, covering every inch of space, as baffled policemen try to keep the peace. “The detail in this photograph is amazing,” said Broadley, who urges people to take the time to examine the pictures and soak in the atmosphere. “Someone even brought a chimp to greet them.”

Also in Miami, there is a close-up of a policeman’s gun and munition, which shocked the boys. “We were from England,” noted McCartney. “We never saw a policeman carrying a gun before. It was jaw-dropping.”

Under the Miami sun, McCartney switched from black-and-white film to highly saturated, deep, luscious color. “The colours were so vibrant,” he writes in the book, describing the sunny city.

“Miami,” he notes, “even in early February, was all blue skies and sapphire seas. I switched to Kodachrome film to do it justice.”

Here, McCartney captured the boys and entourage enjoying the sun, being silly, jumping into pools, and relaxing poolside. “Images taken in the UK are mostly interior scenes, and the group appear sullen,” reflected Broadley. “In America, the group appear transformed, leaping into a swimming pool, laughing and playing it cool in dark glasses.” One of McCartney’s favorite Miami photographs features George by the pool, in cool shades, “living the life—he’s got a bit of a tan; he’s got the shades; he’s got the drink being handed to him by a beautiful girl in a stunning bikini—and then he’s just 20.”

A Special Moment in Time

Eyes of the Storm is a captivating document that records an extraordinary chapter—not just in the Beatles’ own history, but in the history of Britain and the world. Through the journey, we see the four boys’ transformation into global icons, as witnessed from the inside.

Why Eyes of the Storm? “The four of us were like the eyes looking out at the storm,” relates McCartney, “and then you had the cameramen, who were eyes looking in on us, and then it was the audience or the fans—so everywhere you went, there were eyes in the storm.”

There is magic in the Eyes of the Storm. It is McCartney’s wish that “people see the wonder of the period and the kind of innocence of it all”—and they do. As you walk through the show, and as you flick through the book, you get a sense that, yes, the boys wanted fame and basked in it, but that it was always about the music. Indeed, just several years later, when the Beatlemania storm proved too engulfing, and girls’ screams were drowning out the sound of their instruments, the boys made the decision to focus on studio recordings. The world has girls’ deafening screams to thank for the eternal music that transpired as a result.

Eyes of the Storm makes you reflect on the staggering transformation of Western culture over the past six decades—never more evident than in the change to the medium of photography itself. As you watch the explanatory video about the analogue photography process, you realize that ours is an age of instant gratification, endless retakes, and easily corrected results.

There is no “album cover experience,” said Tucci, reflecting on vinyl covers that you studied “for hours and hours” as “you put the record on again and again.” “Album covers were works of art,” agreed McCartney. They were very special, as was photography. “People would have an evening when they showed their photographs to everyone,” he added. “I take pictures on my phone now, but I ask you—when are you going to look at them?”

The National Portrait Gallery should be congratulated for putting so much thought and effort into Eyes of the Storm and not settling for a ‘best of’ selection of prints. After all, these photos are guaranteed attention for their historical value and the iconic stature of their creator. The curators put together a strong story that evolves and engages, as visitors follow the protagonists from one city to another. As they progress, they witness the eruption of Beatlemania, the evolution of the boys themselves, as well as McCartney’s photographic mastery. The soft infusion of sound from the video of the famous Kennedy airport press conference is a stroke of genius—by that point, even if you are not a fan, you will fall for the lads’ boyish charm and feel their excitement as their strong Scouse accents clash with those of the hardy locals. The demonstration of the time-consuming analogue printing process is a gamechanger, too. Those who pause to watch the video will be entranced at the sight of the image slowly appearing on the blank print, as it develops in a chemical bath. McCartney’s handwriting on the walls adds a personal touch, while the contact sheets let visitors view the original photo “session” in its 36-frame entirety, and see which images were “blown up” for the exhibition.

A Photographic Diary

“For McCartney, taking pictures was driven by the same creative impulse as songwriting,” concludes Broadley in the Eyes of the Storm book. “It was what was happening, and it was exciting,” McCartney told her, “so taking pictures of it, writing songs about it—it was all good stuff.”

Eyes of the Storm is a historic diary in pictures, which just happens to belong to Sir Paul McCartney. The book enhances the personal diary aspect with McCartney’s own recollections and reflections on the transformative journey.

Eloquent and insightful, it reveals personal information that both expert fans and Beatles novices will find fascinating—from how The Beatles haircut was born, why fans threw Jelly Beans at them mid-show, and what McCartney thinks of guns, to the invention of 50s rock n’ roll, how Paul and John hitchhiked to Paris, why “without the music of Elvis, Buddy Holly, Little Richard, The Everly Brothers, there wouldn’t have been The Beatles,” what it feels like to be chased by fans, and how success granted The Beatles total creative freedom.

“It is clear from the photographs that The Beatles were a real cultural phenomenon in Britain and beyond, but also one of lasting significance,” Broadley told Quillette.

“By the end of 1964,” McCartney writes in the book, “we had to admit that we would not just fizzle out, as many groups do. We were in the vanguard of something more momentous: a revolution in the culture.” That is “something we might have felt in some primal, unconscious way, but that is a realm that would be taken up later by rock critics and historians”—such as Jill Lepore, who wrote the book’s introduction, and rock critic Ian Fordham, who describes The Beatles as “a Leviathan—a cultural Colossus, whose influence on their musical contemporaries was wholly unprecedented and remains unsurpassed.” Eyes of the Storm provides a magical, front row seat to the singular, historically unique Beatles phenomenon in the making.