Art and Culture

An Egregious Misreading of History

In his first book, Philip Ewell employs mistranslations and deceptively edited quotations to defame Viennese-Jewish music theorist Heinrich Schenker.

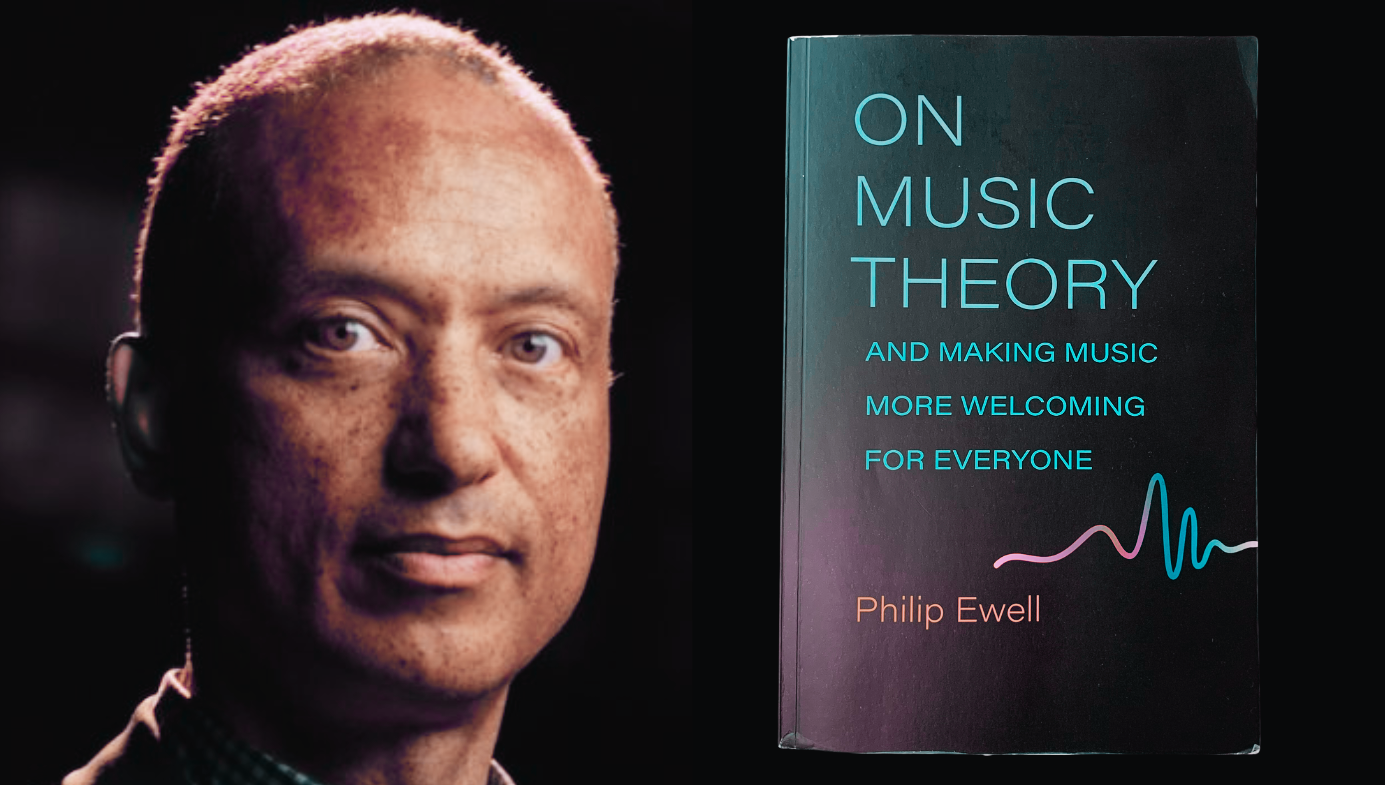

A review of On Music Theory, and Making Music More Welcoming for Everyone by Philip A. Ewell, 332 pages, University of Michigan Press (April 2023)

Music theorist Philip Ewell became a leading antiracist scholar in the disciplines of musicology and music theory after he delivered a plenary talk at the annual meeting of the American Society of Music Theory in November 2019. In On Music Theory, and Making Music More Welcoming for Everyone, his first book, Ewell elaborates on his views about racism and white supremacy in music.

Ewell joins many other scholars in criticizing the historic division within American academic music studies between European music and music of non-European cultures as evidence of deep-seated institutional racism. He also points to music theory’s historic lack of attention to music by POC and women. For Ewell, institutional racism in the discipline of music theory reflects the all-pervasive use of a “white racial frame,” a term he borrows from the sociologist Joe Feagin. Although Ewell focuses on anti-BIPOC racism in the field of music theory, he also includes a chapter about antisemitism in classical music that he deems central to the message of his book. He quotes journalist Bari Weiss’s definition of antisemitism as follows:

I think of [antisemitism] as an ever-morphing conspiracy theory in which Jews play the starring role in spreading evil in the world. … Antisemitism successfully turns Jews into the symbol of whatever a given civilization defines as its most sinister and threatening qualities. … [O]ne must realize what is at the core of this conspiracy theory: blaming Jews for the ills of a society, something that happens often at times of upheaval and social strife. (p242)

However, Ewell’s book is itself a prime example of this conspiratorial thinking. He structures his argument as an exposition of racism and white supremacy in society as a whole, and in music in particular, all of which he links to the Viennese-Jewish music theorist Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935).

Schenker was a musicologist and a theorist. He published a meticulous edition of Beethoven’s piano sonatas and developed a method of graphic musical analysis that articulates the relationship between harmony and counterpoint in a musical composition. Schenker serves as a useful pawn in Ewell’s argument because his ideas have been employed, in watered-down fashion, throughout the field of American music theory for the past 40 years. Ewell does not simply attribute racist sentiments to Schenker; he claims that through Schenker’s baleful influence, they have been transmitted throughout the musical world, poisoning the entire discipline.

Schenker, racism, and antisemitism

Ewell employs mistranslations and deceptively edited quotations in order to connect Schenker to the most loathsome aspects of racism in American and European history. He relates his exposition of Schenker’s alleged crimes to the 1619 Project, which serves as a model for his own proposal to date the history of racism in music theory to 1855. That was the year that Arthur de Gobineau’s Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines (“Essay on the Inequality of Human Races”) was published.

Ewell’s fabrication of evidence concerning Schenker’s supposed interest in Gobineau’s treatise is typical of his method. He begins by quoting music theorist Thomas Christensen’s discussion of 19th-century musicologist François-Joseph Fétis’s interest in Gobineau’s Essai:

The writings on race of Arthur de Gobineau may be an extreme example of this [racial] bias, with his adulation of the pure blood of the great white Aryan race and his dire warning about racial miscegenation leading to the decline of Western civilization, but they are nonetheless a sobering indicator. All the more sobering is to discover that Fétis owned a copy of Gobineau’s notorious tract and evidently made much use of it. (p29)

Ewell links both Fétis and Gobineau to Schenker, citing mentions of Gobineau in Schenker’s diary, letters, and his 1921 essay “The Mission of German Genius” to prove that Schenker embraced the racism of Gobineau’s Essai (p30). Schenker, however, never seems to have read Gobineau’s Essai. Rather, he read Gobineau’s lament on France’s defeat in 1870 and his novel Les Pléiades (1874). In his diary, Schenker recorded his judgment of Gobineau’s lament, expressing his oft-repeated accusations about the superficiality of the French:

Have read Gobineau’s France’s Fate in the Year 1870—an almost un-French piece written by a Frenchman, who is not afraid to detect and articulate the essence or truth he perceives within the French soul. … [H]e might have arrived at the conclusion that the French soul,—innately, as well as due to its impious pride—is destined to remain fixed in the realm of the perfunctory and the prosaic, and from there will surely tend to excess in all directions. (diary entry, July 7th, 1918)

In “The Mission of German Genius,” Schenker cites France’s Fate in the Year 1870 in a rant about the defeat of Germany in World War I, without any racial insinuations:

[I]t is thoroughly perverse to picture oneself demoted to common house servant, even yard dog, forced to show servility and self-deprecation (utterly inappropriately) toward one of those nations [English, French, Italians, Slavs], for example, in deference to the constant mistrustfulness displayed by the French people,—one has only to read all about this in The Fate of France in the Year 1870 by Gobineau, a Frenchman.

Why, we may ask, did Schenker have such an obsessive hatred of the French? While Schenker repeatedly enunciated vociferous German nationalist sentiments versus the French in his publications, his letters and diaries provide a different motive. Schenker, as a Jew, despised the French because of the bitter, drawn-out Dreyfus Affair (1894–1906), to which he returned repeatedly in his diary. In 1899, when Captain Alfred Dreyfus was convicted of treason for the second time, Schenker wrote, “At the end of the 19th century, good Catholic Frenchmen are burning the Jew Dreyfus at the stake of perjuries!” (diary entry, September 1899). Shortly after World War I began, Schenker returned to the Dreyfus Affair as proof of the French predisposition to deception and treachery: “This involuntary desire for the truth, after the fact, is reminiscent of the Dreyfus Affair; even in those days the French nation made a great fuss over their love for the truth, but of course only after they had defiled themselves with the most dishonorable orgy of perjury” (diary entry, August 26th, 1914).

Schenker hated the Russians with equal fervor, due to the relentless Russian persecution of the Jews throughout his lifetime: the restrictive May Laws of 1882, which precipitated the emigration of over two million Jews from the Russian Empire; numerous pogroms throughout the Empire that took place over a period of four decades; the Beilis blood libel case of 1913, in which a Jew was accused of ritual murder (the murder of a Christian child to use its blood in Jewish religious ritual); and the Russian expulsion of the entire Jewish population of Habsburg Galicia, Schenker’s home province, during World War I. In 1913, Schenker mentioned the Beilis ritual murder trial with horror in his diary: “In Kiev a ritual murder trial is taking place in which the law is, from the outset, quite obviously supporting the ritual murder [charge]! The mere fact of the matter … is an indictment of the Russian nation and at the same time a guilty verdict against it!” (diary entry, October 9th, 1913).

Ewell, a specialist in Russian music theory, criticizes Schenker for his condemnation of the Russians. He uses Schenker’s contempt for the relentless oppressors of his fellow Jews to create a narrative in which Schenker supposedly derided the Slavs because of their racial inferiority to German Aryans, thus “proving” Schenker’s adherence to Nazi racial ideology (p97). Ewell gives his attack on Schenker a novel twist by conscripting Russians into his intersectional BIPOC/LGBTQ alliance, asserting that the music of the Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) is undervalued in Western Europe and America because he would have been considered non-white: “Rimsky-Korsakov was both white and male, though as a Russian Slav and Eastern Orthodox, he would probably not have been considered white during his lifetime, neither in Europe nor in the United States” (p78).

In his publications, Schenker vigorously supported German culture as well as German political and military goals. He repeatedly invoked a list of “German greats,” a rhetorical device that has led many scholars to accuse him of German racialist nationalism. Schenker’s enumeration of the great figures of German culture echoed his Jewish contemporaries, such as the renowned German-Jewish philosopher Hermann Cohen (1842–1918). In 1915, during World War I, Cohen published Deutschtum und Judentum in an attempt to demonstrate the spiritual unity between Germans and Jews. Like Schenker, Cohen enumerated a list of German “greats”: “We not only produced Kant and Goethe, but also Schopenhauer and Nietzsche … not only Mozart and Bach and Beethoven, but also Wagner.”

In private, however, Schenker expressed deep apprehension about the Germans. In 1932, he described Sholem Asch’s Von den Vätern, a portrait of traditional Jewish shtetl life, as “documentary” evidence that could serve as a source for the battle against antisemitism (diary entry, January 21st, 1932). Schenker’s strident support for Germany was a function, not of German ethnic chauvinism and racism, but of his marginal status as a member of a stigmatized minority that vainly aspired to participate on equal terms in the majority culture. In a 1933 letter to his student Oswald Jonas, Schenker wrote, “If this musical revelation [interest in Schenker’s theories] will come about better and more easily, provided we desist from offending the musical heathens, let us avoid anything that is unnecessary … two Jews [Jonas and Schenker] at once would be too much for antipathetic minds.”

Ewell contends that Schenker drew up a list of 12 great (primarily German) composers, to which white music theorists have been in thrall ever since. According to the music theorist William Rothstein, however, Schenker’s “list” was actually compiled by Sylvan Kalib in 1973, 38 years after his death. One of the major concerns of Schenker’s students and early disciples was to broaden the applicability of his method to early music, 20th-century music, and the operas of Richard Wagner, rather than addressing only a narrow canonical repertoire. Ewell does not appear to realize that Schenker denigrated Wagner precisely because he abhorred German racialist nationalism. He repeatedly attacked Wagner as both a musical and moral failure, writing of Wagner’s “seriously compromised humanity” and mocking the notion that Wagner was a genius: “For the sake of a Wagner, the world is prepared to conceive a type of genius that lies even beyond the realm of goodness; it would surely not concede the same for a true genius—who of course would need no such thing” (diary entry, May 23rd, 1913).

Schenker’s “racist” quotations

The heart of Ewell’s argument is a series of quotations taken from Schenker’s publications, letters, and diary that purport to illustrate his racism. For instance, he quotes “The Mission of German Genius” to establish Schenker’s antiblack racism:

Is it not the League of Nations that also, for example, placed the filthy French in such oafish control of Germany’s Saarland, and permitted in the regions occupied by them the ignominy of its black troops—the advance party of its genitalitis, of the flesh of its flesh, of the cannibal spirit of its spirit.

Ewell comments:

In this last quotation, note the homoerotic fetishization and objectification of the black male body, in speaking of the genitals and “flesh of its flesh,” that was common in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe and that represents a further dehumanizing of blacks. Such fetishization and objectification of the black body were also mainstays of biological racism, of course. Schenker’s linkage of blacks with cannibalism, promoting the vile stereotype of the “African savage,” should only be understood as a grotesque pathology. (p99)

Ewell, however, abbreviates the quotation to obscure its meaning:

Is it not the League of Nations that also, for example, placed the filthy French in such oafish control of Germany’s Saarland, and permitted in the regions occupied by them the ignominy of their black troops—the advance party of their [French] genitalitis, of the flesh of their flesh, of the cannibal spirit of their spirit—and similarly allowed all the impudent incursions by Czechs, Poles, Yugoslavs, etc.? Then, prudently, after fifteen years, by which time of course Italian and French banditry will have eradicated all trace of German character from the stolen territory, the League will step onto the world stage full of moral righteousness and cynically offer those regions the right to self-determination. [my italics]

Schenker was clearly denouncing the “cannibal French” (a term he uses on other occasions as well)—not their black troops—for their encroachment on German territory, but Ewell attacks Schenker for expressing antiblack racist fantasies.

Ewell also singles out Schenker for his assertion that blacks are not capable of ruling themselves, “acknowledging his belief that blacks, incapable of self-governance, are the lowest form of human being—in fact, subhuman in Schenker’s understanding” (p97). Schenker was a loyal subject of the Emperor Franz Joseph and a vocal advocate of monarchical government. Like all 19th-century conservative political theorists, he evoked the murder and mayhem generated by the French revolution in order to condemn democracy as a destructive ideology. In the contested text, Schenker wrote that all human beings—not only black Africans—are incapable of self-governance:

Since we have deviated from nature, no longer hop around on branches and nourish ourselves on grass and the like, but instead have entered into the artifice of a state, it is out of the question that humankind can come to terms with it. If Mozart, Beethoven, were to compose a state according to his feeling for primordial laws, then it would work, but the mass does not even know that it is a matter of an artifice which, as such, needs falsifications, not to mention that in its lack of talent the mass would find means, particularly today, when even negroes proclaim that they want to govern themselves because they, too, can achieve it (!?) [my italics; Ewell’s quotation in bold] (letter to August Halm, September 25th, 1922)

Schenker employed the term “Aryan” only as a form of abuse. In 1929, he wrote in his diary of “Aryan extortion” (diary entry, August 2nd, 1929); in 1933, of “Aryan shrewdness” (diary entry, September 29th, 1933). Nevertheless, Ewell seizes on Schenker’s use of the term Menschenhumus to prove the latter’s adherence to German racialist nationalism (p96). In his draft of a letter to Wilhelm Furtwängler, Schenker discussed the concept of Humus in terms that show it to be, in his usage, a function of education, rather than the expression of a racist ideology:

So, for example, nothing would be simpler than to begin as early as the lowest school classes with ear-training [Hören-Lehren]. … Thousands of children, who are otherwise lost to music, could be won over anew to it in this way and form the artistic humus [Kunst-Humus] that you seek. (letter draft to Furtwängler, November 11th–16th, 1931)

The word Menschenhumus was employed by German writers with liberal as well as conservative views. For example, in the novel Laudin und die Seinen (“Laudin and His Family,” 1925), the Jewish novelist Jakob Wassermann (1873–1934) used it to describe a prerequisite for liberalization of social attitudes and legal restrictions regarding marriage and sexuality.

Ewell contends that Schenker recoiled from racial mixing and describes Schenker’s belief that “‘Race’ is good, ‘inbreeding’ of race, however, is murky,” as “biological racism” (letter from Schenker to Anthony van Hoboken, January 13th, 1934, p154). It would be more accurate to translate this sentence as “‘Race’ is good, ‘inbreeding’ [breeding within the group; in German, Inzucht], however, is dismal [trüb].” Ewell cites this statement without realizing that Schenker is attacking the concept of racial purity, rather than endorsing it. Twenty years earlier, at the height of World War I, Schenker had acerbically addressed the tragedy of racial prejudice:

The fact that one race hates another proves only that one recognizes the purely animalistic only in the other race, not in one’s own. … To recognize the animal in oneself is something that Nature seems to have made impossible from the outset. … If, then, a European comes across a Japanese, then the ape-like quality of the latter comes all the more decisively to his consciousness, but the less he can recognize it in himself. (diary entry, April 22nd, 1915)

Schenker and the Nazis

Having seemingly demonstrated Schenker’s racism with a series of quotations from his writings, Ewell then proceeds to link him directly to Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. In this way, Ewell believes that he can provide incontrovertible proof that Schenkerian analysis is founded on presuppositions so deeply racist—even genocidal—that they discredit the entire edifice of American music theory: “As further proof, I cite Schenker’s letter in praise of Adolf Hitler, a letter he wrote to his pupil Felix-Eberhard von Cube in May 1933, four months after Hitler’s rise to the German chancellery” (p102). He continues, “Schenker’s praise of Hitler should be unsurprising to anyone who knows Schenker’s writings intimately” (p103).

On the contrary—anyone who “knows Schenker’s writings intimately” will be aware that he repeatedly referred to the Nazis with alarm and contempt, beginning in 1923 (diary entry, August 20th, 1923). In the letter to which Ewell refers, Schenker denounces the Nazis for their persecution of the Jews: “I have been informed of [his friend Moritz] Violin’s situation from time to time by his sister [Fanny Violin], without his knowing it; she recounted terrifying things!” (letter to Cube, May 14th, 1933).

Ewell points to Schenker’s praise for Hitler’s destruction of the German Communist Party as proof of his Nazi allegiances, but many Germans hoped that the Nazis and Communists would neutralize each other, a development that would permit a return to political stability. For example, in a February 1933 letter, the renowned German-Jewish philosopher Martin Buber (1878–1965) suggested that the Nazis “will be sent to fight the proletariat, which will split their party and render it harmless for the time being.” On July 5th, 1933, Schenker wrote optimistically in his diary, “From Mozio [Schenker’s brother Moritz]: he … reports on … the beginning of the decline of the National-Socialist Party in Germany.”

Ewell goes even further in his effort to connect Schenkerism to the Nazis by drawing a loose analogy between Schenker and Jonas Noreika, a Lithuanian war criminal responsible for the murder of almost 2,000 Jews:

In a gripping account of her own grandfather’s Nazi past, Sylvia Foti unpacks history’s revisionism. … Her grandfather, Jonas Noreika, was executed by the Soviets in 1947. … In a telling passage … that can relate directly to Schenkerian revisionist history and to music theory’s consistent whitewashing of Schenker’s transgressions, Foti writes of a four-part process that occurs in creating a national hero out of a complicated figure like her grandfather. (p119)

In addition to linking Schenker to Hitler and the Nazis, Ewell compares Schenker’s refugee students to the American Nazis of the German-American Bund:

As a final example of these links [between American racism and Nazi ideology] and of just how prevalent racist and German nationalist thought was in pre-World War II America, the period in which Schenkerism began in the United States, see Marshall Curry’s short video documentary of a 1939 pro-Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden. (p104)

The first university course expressly about Schenker analysis was not offered until after World War II, when Adele T. Katz taught at Teachers College, Columbia University; “Schenkerism” did not find wide acceptance in the American academic world until the 1980s, not the 1930s. In 1946, the musicologist Paul Henry Lang wrote, “Schenker—and his fervent disciples even more—attack all those who find beauties that cannot be proved by logic or be reduced to their constituent atoms.” Strange as it may seem today, during the mid-20th century, the elegantly descriptive Essays in Musical Analysis by the British musicologist Donald Francis Tovey (1875–1940) took pride of place in the English-speaking world.

Antisemitism, American racism, and Schenker

In On Music Theory, Ewell engages with the problem of antisemitism along with many other forms of prejudice. Quoting Bari Weiss’s definition, he insists on the uniqueness of both Jewish identity (p241) and the scourge of antisemitism (p242): “It’s important not to confuse antisemitism with racism and to have a clear understanding of just what antisemitism is if one is to combat it” (p241). Nevertheless, Ewell relies on reductive racial definitions of antisemitism that harmonize with his general thesis. Subsuming antisemitism to racism and “white supremacy,” Ewell connects the persecution of blacks in America to the Holocaust, citing James Q. Whitman’s book Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (p10). Whitman attempts to show that the Nazis based their anti-Jewish legislation on the corpus of American racist laws, but he also provides evidence that the Nazis looked back to medieval Christian anti-Jewish restrictions.

Having established Schenker’s Nazi affinities to his own satisfaction, Ewell uses Whitman’s tenuous historical parallels to create an analogy between Schenker and the American composer and white supremacist political activist John Powell. By employing this strategy, Ewell links his denunciation of Schenker to the struggle against antiblack racism in America, a line of reasoning that he extends by comparing Schenker’s refugee students to the American Nazis:

In “Unequal Temperament: The Somatic Acoustics of Racial Difference in the Symphonic Music of John Powell,” Lester Feder unpacks the depths to which white supremacy suffused Powell’s music, and how, like Schenker, Powell himself insisted that his white supremacist beliefs belonged together with his racist beliefs. … Finally, Feder stresses the importance of the German tradition to an American white supremacist like Powell, which comports with the story of Schenker’s American beginnings in the 1930s and 1940s. (p117)

While Ewell compares Schenker to Powell, he neglects to inform the reader of Powell’s collaboration with the black nationalists of his day. Powell befriended the black nationalist activist Marcus Garvey (1887–1940), who in turn, supported Powell’s proposed antimiscegenationist legislation. In November 1925, Garvey wrote:

Mr. Powell and his organization sympathize with us even as we sympathize with them. … I unhesitatingly endorse the race purity idea of Mr. Powell and his organization. … I am asking you, my friends and co-workers, to hear Mr. Powell, whom I have invited to speak to you. (Negro World, November 7th, 1925, in The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, Vol. VI, September 1924–December 1927, p252)

Good Jews and Jewish antisemites

The suggestion that Ewell’s ideas reflect ideological antisemitism within the American black community lies at the center of the Schenker controversy (p157). In response to criticism, Ewell argues that only “patriarchal white supremacy” can be the source of antisemitism: “Again, there is but a single culprit in this American conflagration of hate: the patriarchal white supremacy that has formed our country since its founding in 1776, a supremacy rooted in mythologies of white-male greatness and exceptionalism” (p251). Extending this idea, Ewell maintains that Schenkerians have employed the “white racial frame” to delegitimize condemnation of his crimes by appealing to his Jewish identity as a “get out of jail free” card:

Ever since Schenkerism became a thing in the United States his proponents have used Schenker’s Jewishness as a shield against unwanted criticism, thus creating the “victim narrative” … a narrative that allowed music theory’s white racial frame to turn a reprehensible figure like Schenker into a more palatable figure and, in extreme circumstances, something of a hero. (pp155–56)

Ewell maintains that criticism of his work by Jewish scholars is itself antisemitic, designed to divide blacks from Jews, and Jews from each other:

Though the antiblack sentiment of [Timothy L.] Jackson’s comment is obvious, a less obvious sentiment is the antisemitic one. With this statement, Jackson seeks, in my opinion, to divide not only blacks and Jews, but Jews themselves into two groups, namely, those who will defend Schenker and Schenkerians, and those who will defend Philip Ewell. This subtler message, with the intent of dividing Jews is, simply put, antisemitic, and such attempts at division should be called out when they rear their ugly head. (p252)

Having hypothesized a malicious Jewish attempt to divide the Jewish community, Ewell includes Schenker among the culprits, selectively quoting from a lengthy diary entry from 1915 about the poor Jews of Habsburg Galicia. “Schenker’s beliefs in ‘better circles of people,’” Ewell remarks, “Jews’ lack of ‘good manners,’ and an undesirable ‘Jewish residue’ are remarkably antisemitic sentiments” (pp252–53). Characteristically, Ewell omits a key sentence that reverses the meaning of the text: “Anyone who lives, like them, from hand to mouth, under the most difficult conditions—hated, despised, and ostracized, persecuted, burdened usually with a large family, and underestimated in what they do best (as, for example, in their education)—will find no disposition to assimilate in their shattered being” (diary entry, September 29th, 1915).

Philip Ewell’s coupling of Schenker with the Nazis in order to discredit the discipline of music theory is just one manifestation of the current crisis in American society. The ready acceptance of his egregious misreading of history demonstrates the popularity of reductive notions about race and social justice and the all-pervasive presentism that dominates contemporary academic discourse. Sadly, it also demonstrates the persistence of the mythical image of the Jew in contemporary America.