Art and Culture

The Hammett and Chandler of Gay Detective Fiction

How the books of George Baxt and Joseph Hansen changed the genre.

The Baby boomers often get the credit (or the blame) for having revolutionized popular music, popular cinema, and popular fiction, dragging them out of the doldrums of the 1950s and rejuvenating them with infusions of sex, drugs, profanity, violence, and rock and roll. They also began to explore the lives of certain people—gays, lesbians, racial minorities, drug abusers, etc.—who were largely ignored by the pop culture of previous generations. This, of course, isn’t true, and it gives the boomers too much credit. The boomers benefitted from this revolution but they didn’t start the fire, as baby-boomer Billy Joel famously acknowledged. Many of the key players in the cultural revolutions of the 1960s and beyond were born in the 1920s and 1930s: Kurt Vonnegut, Timothy Leary, Norman Mailer, Allen Ginsberg, Arthur Penn, Sam Peckinpah, Philip K. Dick, Ken Kesey, Elvis Presley, Richard Brautigan, Hunter S. Thompson, and so forth.

I have previously celebrated the contributions that Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset (1922–2012) made to literature in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s by fighting censorship laws that had previously made it illegal to sell books such as Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, and D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Earlier this year, I commemorated the 100th birthday of John Mortimer, another child of the 1920s who did far more than most boomers to help liberalize the popular culture of the English-speaking world. And now, the summer of 2023 brings us two more important centenaries to celebrate.

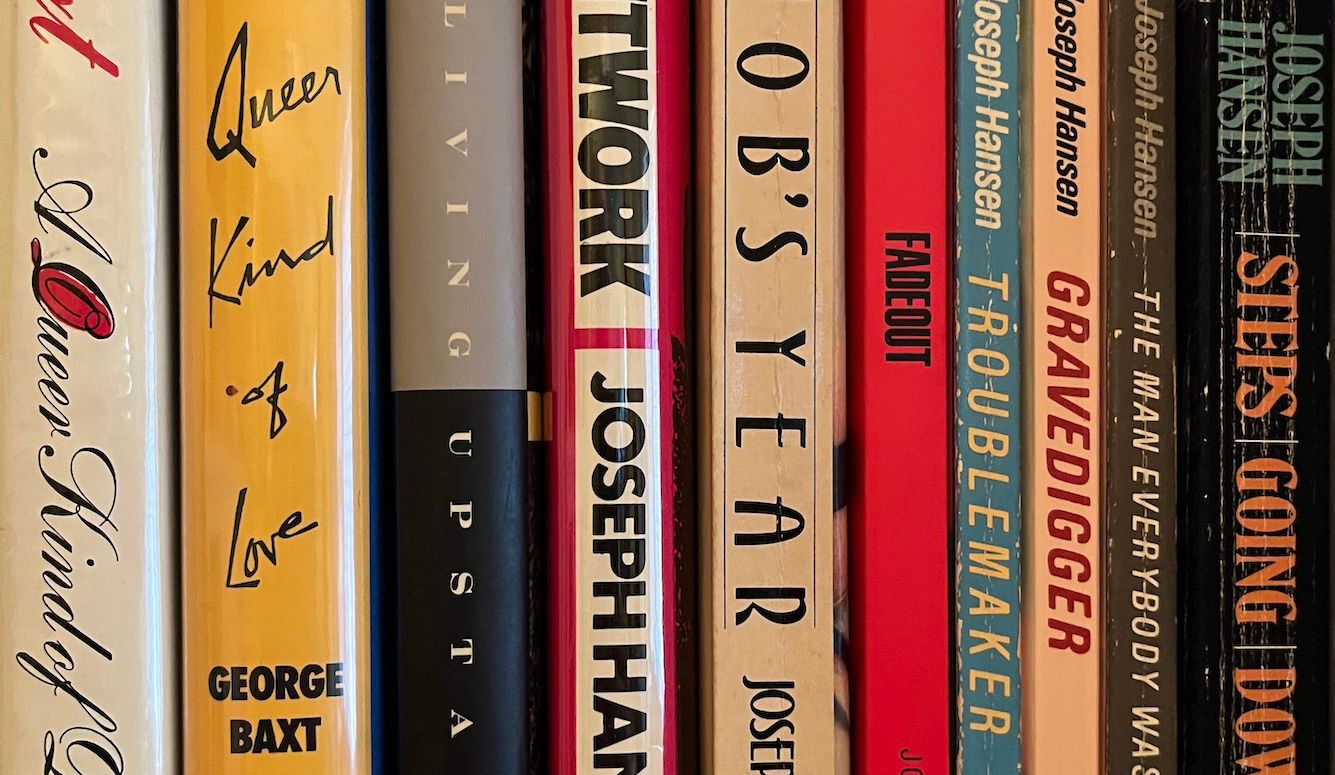

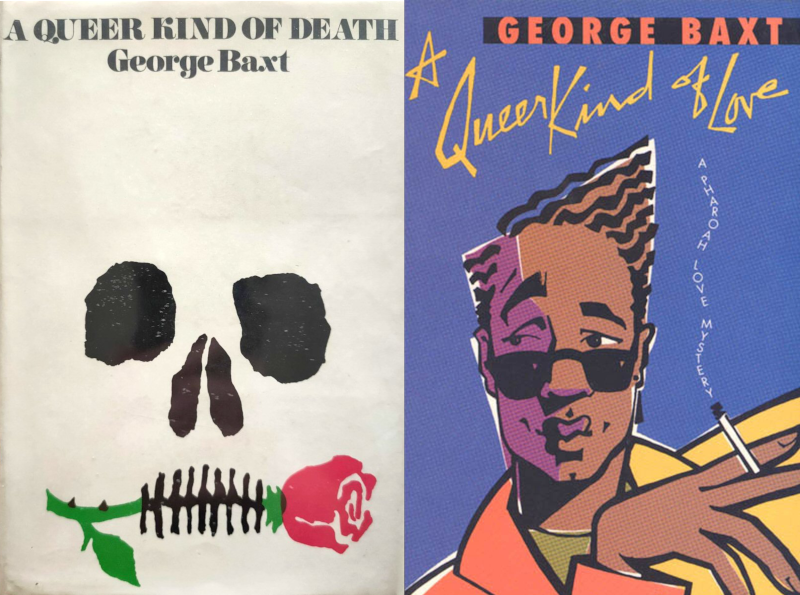

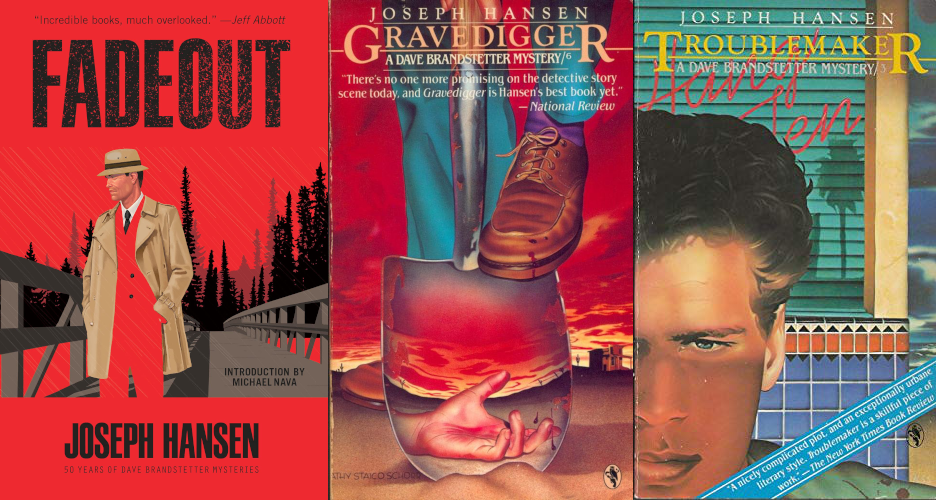

George Baxt, born June 11th, 1923, and Joseph Hansen, born July 19th, 1923, have been called the Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler of gay American detective fiction—each created a series of mystery novels featuring a gay protagonist long before doing so became commonplace. The two men were born about a month apart and died about a year apart (Baxt in 2003; Hansen in 2004). Baxt introduced his gay African-American NYPD detective, Pharoah Love, in a novel called A Queer Kind of Death, which was published in 1966 by Simon and Schuster. Hansen introduced Dave Brandstetter, a gay investigator for Medallion Insurance Company, in the 1970 novel Fadeout, published by Harper and Row. But the novels and their detective protagonists could hardly be more different.

As the name suggests, Pharoah Love (yes, his first name looks misspelled) is a rather flamboyant character. Love (and nearly everyone he interacts with) seems to be a party animal, and he spends more time in bars and nightclubs than at the police precinct building where he works. It is possible that a lot of the people who read A Queer Kind of Death back in the 1960s didn’t even realize that he was gay. Though Love is immediately attracted to murder suspect Seth Piro (he’s moved when he sees Piro crying at the funeral of the murdered man, Ben Bentley), and though Love and Piro eventually become friends and begin talking about moving in together, Baxt never spells out that these men are homosexuals (Piro is married, but he and his wife have separated). Most of the characters appear to be bisexual, but an unsophisticated reader without much experience of the New York queer scene might not have picked up on just how gay much of the cast is. This isn’t because Baxt lacked the courage to make the homosexuality more overt. In 1966, it just wasn’t possible to publish an explicitly homosexual mystery novel with a mainstream press like Simon and Schuster. But no contemporary reader with an ounce of worldliness could fail to see just how queer the book is.

Unfortunately, the novel, though brave, isn’t all that good. One problem is that Love works the word “cat” into nearly every single sentence in a way that just doesn’t seem authentic. Certainly “cat” was a fairly commonplace slang term among the beatnik crowd and lovers of jazz music. You can find plenty of old books, films, and TV shows in which the characters use it. It was a mainstay of Sammy Davis Jr.’s vocabulary, as well as the vocabularies of plenty of other black musicians. But it seems to have been the only bit of hipster slang with which Baxt was familiar. And he has Love using it in odd ways. When inquiring about the sister of the late Ben Bentley, he asks Seth Piro: “What’s with Sister cat?” Pharoah uses that peculiar construction all the time.

“I got to meet that Ella cat real soon.”

“Did she know Sister cat?”

“What time does the Ida cat open for business?”

“Hey, bartender cat.”

“Well, Ida cat, since I like you, I’m going to tell you.”

Of course, he also uses “cat” the way that a contemporary speaker might use “man,” or “bro,” or “dude.”

“I beg to differ, cat. The Food and Drug Administration has a law that says that peyoti [sic] can be used only by a doctor’s prescription. And it is illegal to bring peyoti across state lines for the use of non-Indians. And the deceased was bringing peyoti in from Mexico for use right here in New York. Cat, that means crossing an awful lot of state lines. And somebody was putting up the money for that dead cat’s trips.”

Every page of Baxt’s novel has more cats than an urban animal shelter. In a 1966 review of the novel, Kirkus Reviews’s anonymous critic wrote:

Reader cat, this is all about the death of Ben Bentley, cat (fag, peyote connection, procurer, blackmailer) as it affected switch-hitting Seth (with whom he’d broken up) and Seth’s wife (they’d both shared) and some of the strangest cats of all (a rich recluse and her fag brother) and a Negro detective, Pharoah Love, who not only digs Seth—he becomes his cat baby—but also makes a cat-egorical imperative of all this campy, ofay nonsense. As for the mystery, forget it—and as for the readers—it’s for those who don’t find high drag a drag.

Baxt deserves credit for being a pioneer. But nowadays his book doesn’t come across as especially enlightened. Even Pharoah Love is a problematic hero. He first met Ben Bentley while working undercover to catch male prostitutes. He tells Seth Piro, “I was on the decoy patrol. You know—hang out in fag bars, fag toilets, fag movie houses and make an arrest every now and then. I’ll admit the deceased was pretty drunk the night I pulled him in, but we were a little hungry for entries on the police blotter that week so I collared him.” And, in the end, when Love learns (spoiler alert) that it was Seth Piro who murdered Ben Bentley, he lets someone else take the rap for the murder.

By this point, Love and Piro are living together and Love has no intention of letting a mere murder interfere with his sex life. That’s not an especially good look for American fiction’s first openly gay detective. Over the next 30 years, Baxt published four more Pharoah Love crime novels. I haven’t read them all, but I have read 1994’s A Queer Kind of Love, the penultimate novel in the series, and I am happy to relate that it is largely “cat”-free. But judging from online reviews, the second and third books in the series—1967’s Swing Low Sweet Harriet and 1968’s Topsy and Evil—share many of A Queer Kind of Death’s shortcomings. Both A Queer Kind of Love and 1996’s A Queer Kind of Umbrella were nominated for the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Mystery Fiction, which suggests that, by the ’90s, Baxt had finally turned his gay detective into a character that gay readers could be proud of.

In the late 1960s, however, not all gay readers were happy with Pharoah Love, and Joseph Hansen appears to have been one of them. I haven’t found any absolute proof of this, but Hansen seems to have created his own mystery series as an antidote to the Pharoah Love series. Why do I think this? First of all, there is the name of Hansen’s detective. It would be hard to come up with a less flamboyant name than Dave Brandstetter. It is reminiscent of John Utrelamensky and all of the other instantly forgettable aliases used by the protagonist of the Fletch crime novels. Likewise, while most of the Pharoah Love novels employ the word “queer” in their titles, the Brandstetter novels sound fairly generic: Fadeout, Death Claims, Troublemaker, Gravedigger, Nightwork, etc.

In a 2005 tribute to Hansen published in Mystery File, contributor Richard Moore notes:

Joseph Hansen was an experienced writer well into his 40s when the first Dave Brandstetter novel Fadeout appeared in 1970. The novel was written in 1967 (Hansen said the delay was due to the homosexual background) just a year after George Baxt published A Queer Kind of Death, which featured a black, homosexual detective Pharaoh Love. In a 1984 article in The Armchair Detective, Hansen noted that Love was “far from being a hero.” While not saying outright that he created Brandstetter in response to Love, Hansen did write that he “…set out to write about a decent, upright, caring kind of man, though a man without illusions, a tough-minded veteran insurance investigator who was, as The New Yorker remarked ‘thoroughly and contentedly homosexual.’”

Hansen didn’t want Brandstetter to be a homosexual insurance investigator. He wanted him to be an insurance investigator who happened to be homosexual (Hansen hated the term “gay,” though in his later novels he reluctantly began using it). And he succeeded. The novels bear a strong resemblance to the Lew Archer novels of Ross Macdonald, a detective series that was enjoying great popularity when the first Brandstetter novel was published in 1970. Archer was born around 1916 and Brandstetter in the early 1920s. Both men served in the military during World War II. Both men are residents of Southern California and their cases often take them to small towns outside of the Los Angeles area. But Hansen once noted in an interview that he was bothered by the fact that Ross Macdonald hadn’t given Archer much of a backstory. So, he set out to subvert that crime-fiction convention by giving Brandstetter a fairly detailed personal history. As Fadeout opens, we learn that Brandstetter’s lover of 20 years, Rod Fleming, has recently died of cancer, and that Brandstetter is nearly suicidal with grief. Over the course of the novel we learn how Brandstetter and Fleming first met, how their courtship played out, how their relationship worked despite the fact that they had very different personality types (Rod, the extrovert, loved show tunes while Dave, a more buttoned-down type, preferred classical music).

By the end of the novel, Brandstetter will be tentatively entering into a romantic relationship with a painter named Doug Sawyer. Brandstetter and Sawyer eventually end up living together. In later novels, Sawyer will be replaced in Brandstetter’s affections by Christian, who runs a Polynesian restaurant called The Bamboo Raft. Later on in the 12-book series, we will learn a bit about Mel Fleischer, who became Brandstetter’s first lover when they were both still in high school. We will also be introduced to Cecil Harris, the young black man who will eventually become the next great love of Brandstetter’s life, second only to Rod in his affections. Though he appeared in 18 novels and many short stories, Lew Archer remained something of a cipher throughout his many adventures. Not so Dave Brandstetter. His loves, his losses, his emotions, his tears—Hansen hides none of this from us.

Though Brandstetter has a fairly active sex life, Hansen wisely chose not to include much description of sexual activity in the books. I say this not because I’m squeamish about gay sex but because the sex scenes in most of the pulp detective fiction of the era were generally awful. John D. MacDonald was considered one of the best crime writers of the 1960s and ’70s. He could describe a fistfight nearly as well as Hemingway could describe a bullfight. But when he tried to write a sex scene for his hero Travis McGee, the results were often laughably bad. Consider, for instance, this passage from the 1968 novel The Girl in the Plain Brown Wrapper:

So into the tempos and climates of it again, bodies familiarized now. Fragments. Like things glimpsed at night from a moving train. Dragging whisper-sound of palm on flesh. Deep, deep, slow-thick into the clench of honey, clovery oils, nipples pebbled, lift-clamp of thigh, arrhythmic flesh-clap fading into tempo reattained, held long and longer and longest, then beginning quivorous [sic] hesitation at the end of the deepening, richening beat, a shifting of her, mouth agape, furnace breath, tongue curl, grit of tooth against tooth, hands then cup and pull the rubberous buttocky pumping, her bellows breath whistling exploding the words against my mouth—“Love you. Love you. Love you.” Then somehow opening more, taking deeper, pulling, demanding, a final grinding moaning agony of her, requiring me to drive, batter, cleave, without mercy. Then slowly toppling. The long slope. Hearts trying to leap from chests…

You get the idea. There is no rubberous buttocky pumping in a Dave Brandstetter novel. But somehow the reader comes away with a better idea of Brandstetter’s love life than they are ever likely to get of Travis McGee’s from reading a John D. MacDonald novel. For all of the athletic feats McGee manages to execute in the bedrooms of various scorching hot women, the reader gets very little notion of what, if anything, any of these sexual partners mean to McGee.

The Brandstetter books are one of the hidden gems of 20th-century American crime fiction. Joseph Hansen didn’t write with the poetic flair of, say, Raymond Chandler, but he was at least as gifted a prose stylist as Ross Macdonald. And Brandstetter is a more fully developed character than almost any other American detective of the era. The novels are not fiendishly clever in their plotting. As in the Archer novels, the protagonist tends to knock on a lot of doors, interview various suspects and witnesses, and gradually fill in the pieces of the puzzle. And like the Archer novels, the detective gets lied to a lot and frequently has to return to confront a suspect or witness with evidence of their lies. He may have to do this three or four times before he gets the straight scoop. The solutions to the mysteries can sometimes be a bit far-fetched, but that is another common trope of the genre.

The appeal of the American detective novel, circa 1940–80, was its predictability. These novels tended to take place in a world that made sense. Crime was a problem, sure, but it generally occurred for a reason. And if a police detective or PI was smart and dogged enough, he could usually figure out exactly how and why it happened, and he would bring the bad guy to justice in the end. Few writers employed this formula to greater effect than Joseph Hansen. Dave Brandstetter didn’t specialize in cases involving homosexual victims or suspects, but his ability to recognize closeted gays and lesbians often gave him an advantage over the cops. He is able to see possible motives for blackmail, extortion, or even murder that might be invisible to a detective with no gaydar. His books often feature other homosexual characters but they are no likelier to be angels or demons than any of the heterosexual characters in the story.

The 1970s were a high-water mark for American TV detectives, with all sorts of intriguing PIs making their debuts. Audiences were offered rumpled detectives (Columbo), fat detectives (Cannon), old detectives (Barnaby Jones, the Snoop Sisters), young detectives (Richie Brockleman), ex-con detectives (Rockford), ex-cop detectives (Harry O.), ex-priest detectives (Sarge), Jewish detectives (Lannigan’s Rabbi), blind detectives (Longstreet), smoking hot detectives (Charlie’s Angels), cowboy detectives (McCloud), black detectives (Tenafly, Shaft), and nearly every other variety of detective, including Lew Archer, who was portrayed by Brian Keith in a short-lived series based on Ross Macdonald’s books.

But American TV audiences were not given a gay detective. Ironically, one of the most popular TV crime series of the decade was McMillan & Wife, which starred Rock Hudson, one of Hollywood’s most successful gay actors. But Hudson’s homosexuality was a secret to most of the world, and the character he played was not only heterosexual, he was one of the few detectives of the era who was happily married. According to an excellent profile of Joseph Hansen in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Joseph Hansen was approached in the late 1970s by some Hollywood studio executives who wanted to option the film rights to the Brandstetter books. The execs had only one major demand—they wanted to make Brandstetter a heterosexual. Hansen turned them down, and probably lost a great deal of money in the process.

Now would be a great time for a revival of interest in Hansen and his Brandstetter novels, but contemporary mores would probably produce a backlash against both. The Brandstetter books were written at a very different cultural moment. We learn in Fadeout that Rod Fleming once owned a fashionable furniture shop. One of his employees, a Mexican-American woman, had a six-year-old boy named Anselmo. She had no babysitter, so she often brought Anselmo to work with her, where he would nearly die of boredom. Brandstetter stopped by one day and took a shine to poor Anselmo. After that, he began taking the boy to Dodgers games, Disneyland, and elsewhere. He brought him crayons, coloring books, ice cream, cookies, games, puzzles, toys, and other gifts. The two became very close, despite the 28-year difference in their ages.

Later, when Anselmo is 12, Brandstetter meets him at a party that Rod is hosting at a country club. While showering in a cabana near the swimming pool, Brandstetter sees Anselmo peeking into the showers and examining his naked body. This doesn’t surprise him. He has always suspected that Anselmo was gay. A few weeks after Rod’s death, Anselmo, now 17, comes to Brandstetter’s home and lets him know that he’d like to replace Rod as his lover. Brandstetter tells him that it won’t be possible, that Anselmo is too young for such a relationship with a 45-year-old man. But Anselmo is insistent:

“No!” the boy shouted it, meant it. “I’ve been in love with you from six years old. Sure. I didn’t know it was love. I didn’t know what it was. Just a feeling like you were the best, you know? The greatest. I used to wait for you to come to the shop. … And when Rod threw that party and my mom told me you’d be there, I begged her to take me. To see you. I had to ditch school and she didn’t like it. But she let me go because I bugged her so. And then I knew. I was in love with you. That day … You took a shower. You were beautiful, naked. I wanted to get in with you.”

Eventually Brandstetter will relent to Anselmo’s entreaties. Near the end of the novel, the 45-year-old insurance investigator will find himself in bed with the 17-year-old truant. And Hansen will tell the reader that, “Anselmo kissed him with a hungry child’s mouth.”

Contrary to what people nowadays say about the relationship between a 17-year-old girl and a 42-year-old man in Woody Allan’s 1979 film Manhattan, sex between teenage girls and grown men was not an unusual trope in the pop culture of the ’70s. In Breezy, a Clint Eastwood film released three years after the publication of Fadeout, William Holden plays a 55-year-old man who has a sexual adventure with a 17-year-old hippy chick played by Kay Lenz. No one raised an eyebrow (perhaps because few bought a ticket). The 1969 film Twinky (sometimes titled Lola, and sometimes London Affair) tells the story of a 38-year-old writer (played by Charles Bronson, who was actually 48 at the time) who marries a 16-year-old girl (Susan George, who was 19). Norman Thaddeus Vane’s screenplay was autobiographical, based on his own marriage, at the age of 38, to a 16-year-old girl. In 1971, Cher released a single called “Gypsys, Tramps, & Thieves,” about a 16-year-old girl who is impregnated by a man in his 20s. It flew to number one on the American pop charts and became the biggest selling single MCA had ever released up to that time.

In the 1974 episode of Columbo called “Swan Song,” Johnny Cash plays a 40-something singer having an extramarital affair with a woman more than half his age, an affair that began when she was only 16. None of this was particularly shocking to most Americans of the 1970s. But I suspect that Dave Brandstetter having sex with a minor, whom he has apparently been “grooming” since the boy was six, would not sit well with a lot of contemporary readers. In a review of Hansen’s novel Job’s Year (a standalone book not featuring Brandstetter), a Goodreads user wrote of Hansen’s work:

In each of the 3 books I’ve read, a main male character somewhere between late 30s and mid 50s has romantic feelings for a 16-year-old boy and acts on them. In 2 of the books, it is the boy who first comes on to the main character, and the protagonist treats the boys like adults, so this decreases the ick factor, but doesn’t erase it. The boy in this book seems the most immature and boyish of the three, which made this the creepiest.

Since this was not unusual in heterosexual literature of the mid-20th century, it seems that Hansen is being held to a higher standard than his contemporaries because he was gay. But Hansen’s entire project was about taking the tropes of heterosexual pop fiction and giving them a gay twist. That seemed to be understood in the 1970s, even by conservatives. My paperback copy of Gravedigger carries this blurb from a National Review writer: “There’s no one more promising on the detective story scene today, and Gravedigger is Hansen’s best book yet.”

Joseph Hansen’s biography is nearly as interesting as his fiction. He was married for 51 years to artist Jane Bancroft, who was a lesbian. Such pairings weren’t all that rare back before same-sex marriage was legal. Often it allowed gays and lesbians to put on a public appearance of heterosexuality, granting them a freedom from suspicion that might not be offered to a 50-year-old man or woman who had never married. Back in the 1940s and ’50s, when a man who had been married for 30 years told friends he was going on a fishing vacation with a buddy, it raised few eyebrows. But a never-married man going off for a weekend trip with another man might provoke gossip. In Hansen’s case, the marriage doesn’t appear to have been merely a guise. As his New York Times obituary noted, Hansen insisted that his marriage was that of “a gay man and a woman who happen to love each other,” and they remained married until Bancroft’s death in 1994. (The union produced one child, Barbara, who later transitioned and became Daniel James Hansen.)

Plenty of fictional detectives in the Western tradition—Auguste Dupin, Nero Wolfe, Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, etc.—have been described by various literary scholars as “coded gay,” meaning they were given certain traits (Poirot’s fussiness about his appearance, Wolfe’s and Holmes’s distaste for female company, etc.) that would have suggested to sharp readers of bygone eras that these men and women were homosexuals without the author having to say so. But not until George Baxt and Joseph Hansen came along did any American writers have the courage to create a series of novels about an openly gay detective.

Baxt kicked open the door of American popular fiction, ushered in his gay detective Pharoah Love, and told him to make himself at home. But it was Joseph Hansen who filled the house with offspring. At Goodreads, a list entitled “Gay Detective Cop Books” contains 237 titles and it is far from exhaustive. In 2021, the website Crime Reads published an essay called “24 Queer Crime Novels To Read All Year Long.” Most contemporary queer detectives seem to trace their lineage back to Dave Brandstetter, whose homosexuality is just one of many character traits. Pharoah Love once told an acquaintance, “I’m a cat like all the other cats, baby.” But I suspect he was just a little too over-the-top to be embraced as a model by the authors of most contemporary gay mystery novels. And I suspect he’d be okay with that.