Art and Culture

Belafonte Reappraised

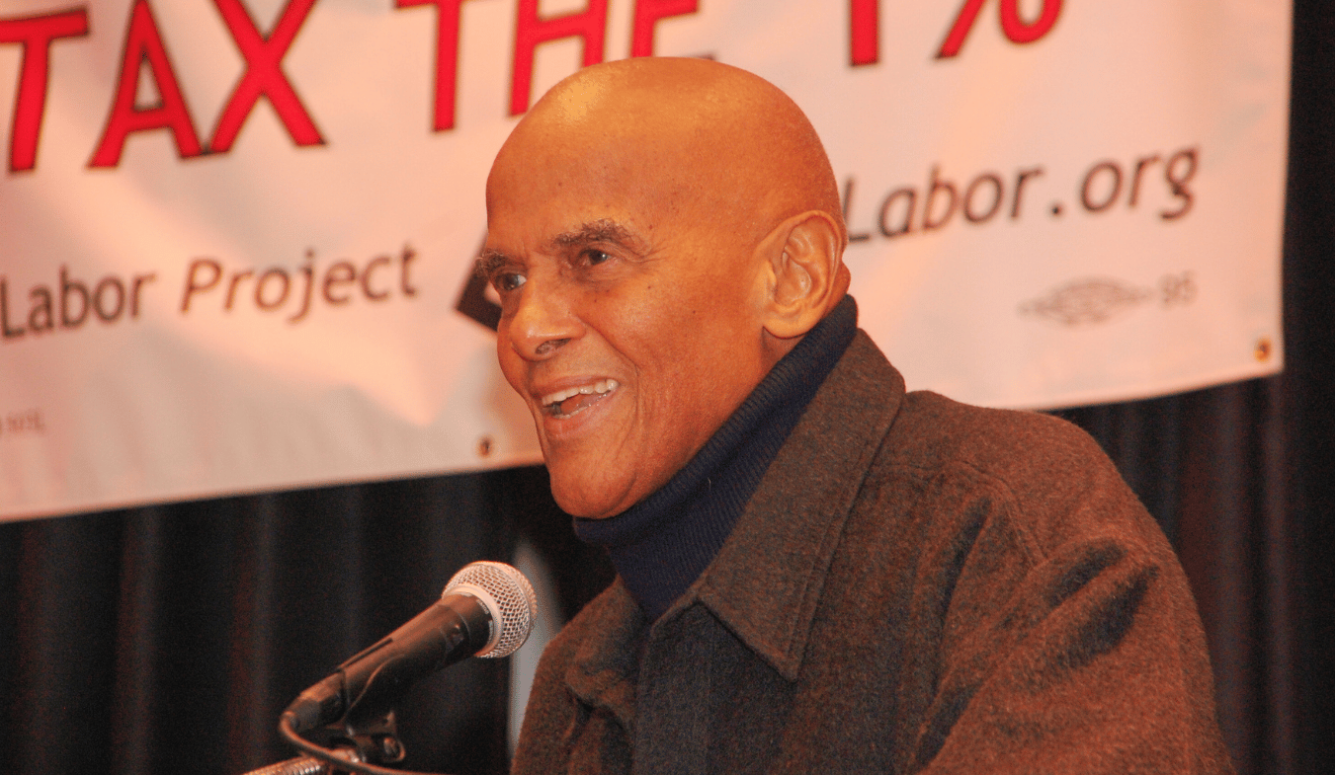

Neither hagiographers nor haters of the late musician, actor, and activist have managed to get him right.

Harry Belafonte’s death at the age of 96 on April 25th produced a cascade of laudatory reminiscences and obituaries. All of these rightfully emphasized his contribution to American music—African-American folk music and calypso music of the Caribbean islands, in particular—and to the nonviolent Civil Rights movement of the 1960s led by Martin Luther King, Jr. By the time the Civil Rights movement arose in the 1950s and 1960s, Belafonte had already become a major recording artist and star. His 1956 LP Calypso was the first gold record, selling over a million copies in the United States alone, and remaining at the top of the Billboard album chart for 31 weeks.

Belafonte used his newfound wealth to fund the Civil Rights movement, and continued to do so for the rest of his life. He was also a prominent promoter of a cultural boycott of apartheid South Africa in the 1980s, and responsible for organizing the all-star recording of ‘We Are the World’ to raise money for African famine relief. His obituary in the New York Times summarized his achievements like this:

At a time when segregation was still widespread and Black faces were still a rarity on screens large and small, Mr. Belafonte’s ascent to the upper echelon of show business was historic. He was not the first Black entertainer to transcend racial boundaries; Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald and others had achieved stardom before him. But none had made as much of a splash as he did, and for a while no one in music, Black or white, was bigger.

About his commitment to social justice and civil rights, the Times added:

Early in his career, he befriended the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and became not just a lifelong friend but also an ardent supporter of Dr. King and the quest for racial equality he personified. He put up much of the seed money to help start the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and was one of the principal fund-raisers for that organization and Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

So far, so good. Others made the same points in their own way, and most slipped into hagiography. In the New Yorker, Amanda Petrusich also treated Belafonte’s political life as unblemished, noting that, besides the Civil Rights movement, he supported “H.I.V./AIDS prevention and treatment, the abolition of nuclear weapons, education, the end of apartheid, and more. Most recently, he served as a co-chair of the Women’s March on Washington, held the day after Donald Trump’s Inauguration.” Well, okay. But did Belafonte, I want to ask, have anything to say about the antisemitism of some of the leaders of the Women’s March, and the attention it received? And did he commit himself to any political causes that a wiser soul might have thought twice about before endorsing?

Very few obituarists could bring themselves to say anything negative about his public life. Jonathan V. Last, editor of the anti-Trump website The Bulwark, included a brief and uncritical appreciation in his “Triad” newsletter. Even the conservative Washington Examiner devoted most of its Belafonte obituary to praise, including just a few short lines of criticism:

Belafonte never lost his appetite for a fight. He was deeply involved in the opposition to apartheid in South Africa. Less nobly, he had kind things to say about Fidel Castro and most uncharitable things to say about George W. Bush; such ill-considered and (worst of all) blandly predictable far-left pronunciamentos were unworthy of a genuine civil rights icon.

A number of rightwing websites responded to these tributes with hatchet jobs, offering perfunctory praise before moving on to their real point—that Belafonte was simply a tool of the Communists. In the Federalist, Ron Capshaw promised to reveal, “What Corporate Media Won’t Tell You About Lifelong Communist Harry Belafonte.” Capshaw acknowledges, with apparent reluctance, that “in some ways he was an admirable figure,” but the main thrust of his article is that Belafonte supported communist regimes when they were “at their bloodiest.”

That is an exaggeration. The pre-Gorbachev Soviet Union was certainly repressive, but nothing like as murderous as it was during the genocidal Stalin era. And Capshaw probably ought to have mentioned that Belafonte insisted in his bestselling 2011 memoir that he had never been a communist. Nevertheless, whether or not Belafonte was ever a member of the American Communist Party, he certainly moved in communist circles, and over a lifetime of activism, he managed to get a lot of things profoundly wrong.

What, then, is the truth about Harry Belafonte’s politics? Were they reprehensible, or are attacks like Capshaw’s simply McCarthyite attempts to tarnish the posthumous reputation of an American hero?

A proper understanding of Belafonte’s political views must begin by considering the influence of the man he called his artistic and political mentor—the late African-American actor and bass-baritone, Paul Robeson. I have written a great deal about Robeson’s life, including a lengthy analysis for the American Interest, in which I argued that Robeson squandered his reputation with his lifelong devotion to the Soviet Union and Stalin.

No one defended Stalin and attacked his critics more vehemently than Robeson. American blacks, he argued, had to pay regular homage to Soviet totalitarianism because the Soviet Union’s very existence gave American blacks “the chance of our achieving our complete liberation.” Upon Stalin’s death, he wrote that the dictator had “charted the direction of our present and future struggles.” I concluded that by “holding to his life-long support of the Soviet Union, which he regarded as the freest country on earth, Robeson took as an ally a totalitarian regime that was the enemy of the very goals in which he believed.”

Robeson’s membership of the Communist Party was proven after his death. But when he was asked about it by the House Un-American Activities Committee, he offered these duplicitous words: “What do you mean by the Communist Party? As far as I know it is a legal party like the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. Do you mean a party of people who have sacrificed for my people and for all Americans and workers, that they can live in dignity? Do you mean that party?”

Belafonte was also accused of being a communist, and in his memoir, he flatly denied it:

I went to lectures at the Jefferson School at Sixth Avenue, which openly billed itself as an institute of Marxist thought affiliated with the American Communist Party. [It was actually the official school of Marxist-Leninism, run and owned by the CPUSA.] … I liked the spirit of brotherhood that those meetings nurtured. But I never signed on as a member of the American Socialist or Communist Party, or even viewed myself as a fellow traveler, as the jargon of the day had it. Perhaps the notion of joining anything held me back.

This is disingenuous. While we have no evidence that Belafonte was ever a CPUSA member, as Robeson’s preeminent disciple, he was certainly a fellow traveler. Belafonte also corroborated my analysis of Robeson: “About Stalin and communism,” he wrote, “[Robeson had] begun to have his doubts, especially as Russian artists that he’d met began to disappear, but the last thing he wanted was to give J. Edgar Hoover and the rest of his U.S. prosecutors any reason to crow.” And unlike Robeson, Belafonte wrote that, had the FBI asked him about his loyalty to the US, he would have responded: “I was loyal to America and its Constitution. … I no more advocated the downfall of the United States Government than they did. When I spoke out on political issues, it was with the full understanding and appreciation that I lived in a democracy where I could express those views.” This unambiguous statement is not one that many communists would have made.

Belafonte’s career took off just as Robeson’s was coming to an end, by which point, America was a very different place. Robeson’s popularity surged during WWII—the years of the US-Soviet alliance against Nazi Germany and fascism—when his pro-Stalin views did not hurt his growing fame and celebrity. Belafonte’s fame coincided with the peak of Wisconsin Senator Joe McCarthy’s influence and power, an era historians call “the second Red Scare.” The livelihoods and reputations of many artists were pitilessly destroyed during this period. But America was not the communist bloc. No one was thrown into anything approximating the Soviet Gulag, nor was anyone murdered for their views like most of the leaders of Czechoslovakia, who were found guilty of treason and hanged by the same regime they had served. But as the Cold War began, Belafonte proved to be a willing supporter of almost every major communist-inspired cause.

The most important of these was the public support he offered to the third-party candidacy of Henry A. Wallace in the 1948 election. Wallace ran as a “peace” candidate and as a defender of Soviet foreign policy. His Progressive Party boldly opposed American racism, of course, and Wallace showed guts by campaigning in the southern states, with the stipulation that he would only speak before integrated audiences. As Belafonte explained in a 1998 PBS interview, “No one spoke up against the racist laws that existed with any effectiveness who was aspiring to office. So we had to create a new forum … creating the Progressive Party and Henry Wallace … gave a lot of us a place around which to rally, a place around to which articulate our grievances, a place around which to do analysis and to do outreach.”

Belafonte either ignored or was ignorant of the real reason that the Soviets told their American comrades to form a new party and break with the Democrats—it allowed American communists to campaign in support of Soviet foreign policy. And as historian Thomas Devine subsequently demonstrated, the Progressive Party was formed and run by communists. Its leader, C.B. “Beanie” Baldwin, was a secret member of the CPUSA. As a result, Belafonte was temporarily blacklisted. When TV host Ed Sullivan, the most important supporter of talent at that time, heard about this, he asked Belafonte for a meeting.

Belafonte admitted that he was indeed a member or participant of every group Sullivan mentioned. But, he added, “as an American and as a human being, I lend my energy and my time to end hate, to end racism, to look for a better day for all of us.” He explained that Lincoln and Jefferson were his abiding inspirations, and he refused to disavow his political commitments “for the privilege of being on your program.” Then he walked out. To the surprise of many contemporary observers, Sullivan went ahead and booked Belafonte anyway, and his subsequent appearances allowed him to avoid the treatment meted out to radical singers like Pete Seeger, who was kept off US TV until the ’60s.

Is it likely that Belafonte was a member of the American Communist Party? Many of his associates, including Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, were members, but none of them, except for playwright Lorraine Hansberry, openly acknowledged it. Bob De Cormier was an indispensable part of Belafonte’s entourage for years, acting as his musical director, conductor, arranger, and director of the Belafonte Singers. I knew De Cormier well—he was my high-school and summer-camp music teacher, and director of the Jewish Young Folksingers, of which I was a part. He was also a communist and the FBI knew it, which is why he was credited on records and in programs for many years as Bob Corman. De Cormier later admitted his membership of the Communist Party, but like many of his contemporaries, he denied it for years—long after the blacklists were discontinued. So the fact that Belafonte denied that he had been a Communist Party member doesn’t tell us very much. But if he was not an official member, he certainly had a bad habit of behaving like a dupe of the totalitarian Left.

The American Communist Party was not slow to exploit the problem of racism during the first half of the 20th century, evidenced by segregation, discrimination, and the lynching of black Americans. Such things, communists argued, were proof of the moral bankruptcy of the United States’ political system, which they compared to the supposedly anti-racist record of the Soviet Union. Consequently, American blacks joined the CPUSA in droves on the understanding that they would forge a partnership for proletarian revolution with the wider working class. Initially, the Party favored an independent new nation for American blacks in the so-called “Black Belt” of the South, where they were deprived of the right to vote. It was not until the late 1950s that Moscow instructed the US Party to abandon that policy and to work instead with the emerging Civil Rights movement. The Party quickly expelled Harry Haywood, a leading black communist who continued to support the “Negro Nation” theory, and promoted integrationists in his place.

Most famously, the CPUSA fought to prove the innocence of the so-called “Scottsboro Boys,” nine young black hobos pulled off a freight train in Alabama and accused of raping two white women in 1931. They were convicted and sentenced to death by an all-white jury in a trial held in Scottsboro. Under the auspices of its legal arm, the International Labor Defense, the American Communist Party offered legal assistance and support. Following multiple appeals, the case eventually came before the Supreme Court in October 1932. The Court reversed the guilty verdicts, ruling that they had violated the due-process clause of the US Constitution. The State of Alabama ordered new trials, but one of the alleged victims retracted her testimony and admitted that no rape had taken place. Undeterred, Alabama continued to pursue prosecution and eventually secured the conviction of four of the accused, who were handed lengthy prison sentences. It wasn’t until 2013 that Alabama finally granted them a symbolic posthumous pardon.

Long years of Communist Party activism fighting racial injustice attracted the support of many black Americans, particularly in the arts and entertainment. During the 1930s and ’40s, even Duke Ellington, as Terry Teachout recorded in an essay for Commentary, appeared at events run by various CPUSA front groups. “Like many other blacks,” Teachout observed, “he appreciated the Communist Party’s stance against racism, and his sentiments were widely shared in Harlem.” Which is why Ellington threw his support behind the New York City Council candidacy of the African-American Communist Party leader Benjamin J. Davis in 1943.

In his first memoir, Jackie Robinson acknowledged the major role played by the Daily Worker’s sportswriter Lester Rodney in getting him on the Brooklyn Dodgers’ team. Scores of other prominent black artists operated in the CPUSA milieu. During the 1950s, I saw Dizzy Gillespie appear as the headline act at a benefit gig held by a prominent communist front group. And yet, during this period, Gillespie also went on State Department tours of Europe intended to show Europeans that—contrary to Soviet propaganda—black Americans’ participation in the arts was appreciated. Gillespie was evidently unconcerned by this apparent contradiction.

All of which is to say that Belafonte’s closeness to the Communist Party was hardly unusual. He was appreciative of the opportunities the communists gave him at the beginning of his career, but this often required wilful naiveté or ignorance of the truth. When Martin Luther King said he would break ties with his principal fundraiser and advisor Stanley Levison after Attorney General Bobby Kennedy informed him that Levison was a communist, Belafonte was outraged. Levison, he wrote in his memoir, was a “brilliant tactician and tireless fundraiser” and he insisted that Kennedy’s allegation was false. He became a secret conduit between King and Levison, even working behind the scenes helping Levison write King’s speech for the March on Washington. But as historian David Garrow has demonstrated, Levison was not only a communist, he also acted as the chief money man for the CPUSA. Most writers believed that Levison had severed his ties with the Party in 1957 because he felt it had become ineffective. Garrow shows that Levison was still involved with major Party figures until 1963.

Another of King’s close advisors, Jack O’Dell, was also an important communist figure and a full-time staff member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the civil rights group to which King belonged. Belafonte wrote that King told him: “Everyone knew of his youthful support of communist-related causes.” But the idea that he was a Party member, King continued, “was just [J. Edgar] Hoover’s fantasy; O’Dell had no involvement with the American Communist party.” It was Levison, Garrow notes, who installed O’Dell as head of the SCLC office in New York City. Evidently referring to Levison and O’Dell, King later told his advisor, Bayard Rustin, a pacifist and social democrat, that: “There are things I wanted to say renouncing Communism in theory but they would not go along with it. We wanted to say that it was an alien philosophy contrary to us but they wouldn't go along with it."

It is interesting to compare the speeches King and Belafonte gave when they spoke at different times in East Germany. King spoke at a Lutheran Church in the communist state in September 1964. Historian Paul Kengor writes:

King made two allusions to the wall, built just three years earlier. “For here on either side of the wall are God’s children, and no man-made barrier can obliterate that fact,” he said at one point. And then later: “Wherever reconciliation is taking place, wherever men are ‘breaking down the dividing walls of hostility’ which separate them from their brothers, there Christ continues to perform his ministry.” Here was affirmation of the inherent, God-given dignity of all human beings, regardless of whether communism denied that dignity, denied that God and denied free passage from East to West.

The East German authorities had hoped, his official translator noted, that by exposing American racism, King would provide the regime with fodder for propaganda. Instead, King used a Christian message to compare the suffering of the East Germans to that of American blacks. By detailing the nonviolent struggle of blacks in the US, King was asking his audience to mount their own resistance. After the speech, the church chorus sang, “Go Down Moses,” an allusion to the Jews escaping slavery in Egypt for the promised land. The message was obvious, which is probably why the authorities decided not to print or distribute King’s speech, even though they had publicized it beforehand.

When Belafonte spoke in East Germany in October 1983, at a “World Peace Concert” run by the official communist youth organization there, he offered a quite different message. He publicly endorsed the Soviet “peace campaign” for unilateral Western disarmament, at a time when the Soviets had placed SS-20 missiles in the German Democratic Republic. And as the New York Times reported, he “attacked the American invasion of Grenada and also criticized the scheduled NATO weapons deployment” of Pershing 2 missiles in West Germany, approved by both Jimmy Carter and his successor Ronald Reagan. In short, Belafonte delivered a speech in a Stalinist prison state supporting Soviet foreign policy in the Cold War. He may have believed that he was doing his bit for human liberty and brotherhood, but his platform was provided by a regime whose secret police waged a perpetual witch-hunt against its entire population.

It is no wonder that Leo Cherne, then head of the International Rescue Committee, rejected a suggestion that the group honor Belafonte. But Cherne went too far. Belafonte, he told the IRC Board, “played a significant relief role in Ethiopia at a time when Ethiopia was under the control of the left wing dictator Mengistu, at the very time that the Castro military forces were playing an active support role.” Years ago, I quoted Cherne’s remarks in an op-ed about Belafonte for the New York Post. I subsequently mentioned them again in a post on PJ Media. I should have looked into it more closely. In this instance, Cherne let his anticommunism obscure what Belafonte actually felt about Mengistu.

In fact, Belafonte saw through the Ethiopian dictator. Mengistu’s charm, he wrote in his memoir, masked “a little Napoleon,” who was “was responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of Ethiopians, many of them children.” If Mengistu preferred not to give this impression, it was simply because he was dependent upon Western aid. Belafonte went to Ethiopia because he hoped to persuade Mengistu’s regime to allow that aid to reach the country’s people. He was not in any way trying to legitimize his authoritarian and pro-Soviet regime.

Unfortunately, Belafonte’s political judgment was extremely erratic. His criticism of conservative black Americans, and even moderate Republicans like the late Colin Powell, is well-documented and predictable. But he also was extremely critical of Barack Obama. In 2017, he told the Daily Beast’s Richard Porton that high expectations among progressives had been misplaced because the president “failed the test” of actually implementing progressive measures. He even announced that Obama lacked “a moral compass,” because “he could have stepped above the political fray and made courageous statements about laws regarding homeland security such as the Patriot Act that are still on our books.” And, of course, Belafonte was unable to resist the “socialism of the fools.” In 2017, he joined Angela Davis, Alice Walker, Danny Glover, and others as co-signatory to an open letter urging a group of athletes not to travel to Israel and to lend their support to the Palestinian fight against the Jewish State.

In his memoir, he acknowledged: “I remained not just liberal but an unabashed lefty. I was still drawn to idealistic left-wing leaders … who seemed to embody the true ideals of socialism.” Unfortunately, the leaders he came to admire the most were totalitarians. With dismaying predictability, he traveled to Venezuela in 2006 to sing the praises of Hugo Chavez, a man who made use of Fidel Castro’s support and secret police. Chavez’s despotic cult of personality would soon crater the economy of his once prosperous state. But in the speech he gave there, Belafonte said that Chavez “seemed far more complex than the swaggering” figure portrayed in “the Western media.” He also claimed that millions of Americans supported Chavez’s socialist revolution. As CBC reported:

“No matter what the greatest tyrant in the world, the greatest terrorist in the world, George W. Bush says, we’re here to tell you: Not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of the America people support your revolution,” Belafonte told Chavez during [a radio and television] broadcast.

“We respect you, admire you, and we are expressing our full solidarity with the Venezuelan people and your revolution,” he added.

Chavez wrecked his country’s economy, ended freedom of the press, and had arrested any Venezuelan who challenged his rule. And yet Belafonte, like many credulous Western radicals, believed Chavez’s state to be more democratic than his own.

Unsurprisingly, Belafonte also was a fan of Fidel Castro, who had built a gruesome one-party communist state in Cuba, and who suppressed all dissidents and permitted no one to run for any office who was not a member of the country’s Communist Party.

Like the New Left, Belafonte replaced the Old Left’s love of the Soviet Union with love of the USSR’s client states in Latin and Central America. In his memoir, he had this to say about Cuba and Castro:

To me, Fidel Castro was still the brave revolutionary who’d overthrown a corrupt regime and was trying to create a socialist utopia. Our trade blockade pleased the right-wing Cuban-American community in Miami, but who were those angry partisans? A lot of them were cogs in the corrupt Batista machine who’d lost their plunder and were still mad about it! Long after the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban missile crisis, I still felt the United States should forge an alliance with Cuba that benefited both countries and gave Castro enough space to make his experiment work.

By the time he wrote that, Cuba’s dismal human rights record was hardly a secret. Imprisoned dissidents included Cuban socialists, social-democrats, trade unionists, and independent self-proclaimed radicals. Belafonte made many trips to visit Castro and Cuba. On one of these, he addressed a rally honoring the Rosenbergs, telling his audience that the Castro regime was “exemplary of the principles the Rosenbergs fought and died for.” He did not seem to mind that their conviction for “conspiracy to commit espionage” was occasioned by supplying military and atomic information to Stalin’s regime, rather than for a commitment to principles of human rights or democracy.

Belafonte must have known about—or even seen—the 1984 documentary Improper Conduct directed by Orlando Jiménez-Leal and Academy Award-winning Cuban-born cinematographer Néstor Almendros. When it was broadcast on PBS, the New York Times reviewer called it “something very rare in films—an intelligent attack on Fidel Castro’s Cuban revolution, mostly as recorded in interviews with 28 Cuban exiles, including former members and supporters of the Castro regime.” The film featured not just regular citizens, but also many “distinguished writers, journalists, playwrights, doctors, poets and painters”—the kinds of artists whom Belafonte cherished in the United States, and who were particularly vulnerable to repression in a police state like Cuba.

Belafonte ignored the early arrest and imprisonment of the US Comandante William Alexander Morgan, the subject of both a PBS documentary and a New Yorker profile, as well as the arrest and decades of imprisonment suffered by another Cuban comandante, Huber Matos, who made the mistake of disagreeing with Castro’s drift towards communism. Those who wanted to know what was really going on in Cuba had plenty of evidence from the start that Castro was building a totalitarian regime based on Marxism-Leninism. If Harry Belafonte saw none of this, it is because he chose to look the other way.

Belafonte was a mass of contradictions. He paid his dues pushing a cart in the streets of the garment industry, and worked hard to become a world-famous singer, actor, and activist. He supported the emerging Civil Rights movement led by Martin Luther King, Jr., but then funded the more radical young upstarts who formed the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) who ended up advocating a radical program of “Black Power.” They ridiculed King as “de Lawd” and installed the revolutionary antiwhite agitator Stokely Carmichael as their leader. Belafonte sought to help the SNCC and King understand each other, but failed. He worked for African freedom, but often uncritically championed new black leaders in Africa who were anything but democrats, claiming that Seke Touré of Guinea “had no choice but to accept aid for his desperate country from the Soviet Union and China.” In his eyes, the US unjustly used that development to shun Guinea as “a communist satellite.”

Like most of us, Harry Belafonte was a deeply imperfect man. At times, he tried to work through his illusions. At others, he retrogressed and sounded like any other communist apologist—a man who called himself a progressive and insisted that communist regimes reflected his values despite copious evidence to the contrary. As he aged, he fell back on old bromides, just as Robeson had done throughout his life. But the lives of complex figures like Harry Belafonte and Paul Robeson are unsuited to either uncritical adulation or thundering condemnation. As we assess their maddeningly inconsistent legacies, we should do so in a spirit of truth and understanding—no matter how impressive their achievements were or how painful some of their choices may have been.