Politics

A Party in Turmoil

Only more pragmatic leadership can renew the SNP and help repair Scotland.

What will the 40 percent (and falling) of Scots separatists do now that their vehicle for independence is spluttering to a halt? Like a clapped-out old car, rust is creeping up its innards, parts of it are falling off, and an incompetent driver is at the wheel who seems to have neither a map nor a clear sense of direction.

For a short time, the Scottish National Party (SNP) led the most vibrant movement of its kind in the modern world, secure in its moral and civic purpose and outperforming all other campaigns for secession. Catalonian separatists are disheartened and disunited while the campaign for the Bavarian independence in Germany was only able to muster 1.7 percent of the vote in the last general election. The SNP’s authoritarian leadership, on the other hand, has managed to keep splits and factionalism to a minimum—until recently, at least.

The case for the independence of what was a sovereign state until the 18th century was pressed with unwearying fervour, larded with flattery of the Scots’ genius and contempt for the (English-dominated) Westminster government. For nearly two decades, the UK-wide parties—Conservative, Labour, and Liberal Democrat—had been consigned to the futile sidelines of political power. Two-thirds of Scots voted to remain in the European Union during the 2016 Brexit referendum, and the SNP’s pledge to rejoin upon winning independence was seen as a way of righting a terrible wrong.

But look at the state of the SNP now. The Scottish police—the eight regional divisions of which the nationalist government controversially collapsed into a national network—are investigating the party. The SNP’s long relationship with its accountants has been terminated by the firm itself, which is refusing to work on the central party’s accounts or those of its Westminster parliamentary party. According to one newspaper report, senior SNP members believe that the arrest of Nicola Sturgeon, the former First Minister, is “imminent.”

SNP members of the Scottish parliament (MSPs), released from the discipline its leadership once imposed, are now noisily objecting to policies they were once compelled to support. One long-loyal MSP, Fergus Ewing, has mounted a swingeing attack on his party’s coalition partner, the tiny Green party, calling them “wine bar pseudo-intellectuals.” The Greens’ policy of phasing out North Sea oil exploration, which the SNP had adopted, Ewing maintains, would cost Scotland “hundreds of thousands of jobs.”

The SNP’s two leaders during the period in which it came to dominate Scots politics were routinely lauded as the two finest politicians in the British Isles, rhetorically inspiring and strategically brilliant. Alex Salmond—party leader from 1990 and First Minister from 2007 to 2014—was the architect of the modern party. His former deputy and protégé, Nicola Sturgeon, was First Minister and party leader from 2014 to March of this year. These two political figures were especially admired by English leftists, who tend to believe that their own country is mired in imperial nostalgia.

Salmond fell heavily from grace after his 2014 resignation, having failed to win what he billed as a “once in a generation” national consultation on the question of Scottish independence. Fifty-five percent of Scots voted No to secession, which was not an overwhelming defeat for the SNP, but an unequivocal rejection of their argument just the same. It was the kind of loss that only someone like Trump could declare a victory. That setback besmirched the once-shining reputation of a politician who had spent the young 21st century visiting a series of humiliations on both the UK government and the Scottish Labour Party. As the SNP took over the national geist, it had swallowed up Labour’s voters leaving the party practically extinct as an electoral force north of the border.

Now saddled with the unfamiliar reputation of a loser, worse was to come for Salmond. In late 2017, he was faced with serious allegations of sexual predation made by 10 female party and government officials. To general surprise, a jury found Salmond not guilty, but the picture that emerged of the former leader during the trial was not a flattering one. Aides felt he could not be trusted with unchaperoned women, and Salmond’s own lawyer was filmed on a train calling his client a “bully” and a “sex pest.” Not unreasonably, Salmond suspected—although he was unable to prove it—that Sturgeon had orchestrated the charges on him.

Salmond based himself largely in London, the city he had once denounced for treating Scotland as a colony. An admirer of Vladimir Putin, he was contracted to present a chat show for the Russian propaganda channel RT. That gig began in 2017, three years after the seizure of Crimea, and only ended (or rather, was suspended “until further notice”) on February 24th, 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine. Earlier that week, Nicola Sturgeon had said she was “appalled” that her former boss was continuing to host a show on the channel and called for RT to be banned.

Surgeon was, at that time, still widely admired as a radical social democrat, dedicated to cleansing Scotland of its association with imperial England. As a woman of militant passion, she continued to whip up a fervent popular desire to leave a UK which was caught in what the influential nationalist writer Tom Nairn called the “chronic disorder of imperial decline.” While Salmond’s reputation went into a tailspin, Sturgeon seemed to be in absolute command of her public persona and her party.

But now Sturgeon has fallen hard too—even more publicly than Salmond and perhaps more consequentially. She has pulled parts of the SNP’s structure down with her, and what remains is still trembling. A few days after her resignation, her husband and SNP CEO, Peter Murrell, was arrested at their home as part of an investigation into alleged fundraising irregularities, and taken to a Glasgow police station for over 11 hours of questioning. He was eventually released pending further enquiries. Last week, the party Treasurer, Colin Beattie, was also arrested. He resigned three days later.

Much is now speculation, and tough Scots laws penalise anything beyond the publicly available facts. But we know that a top-of-the-range, £110,000 motor-home, bought with party funds and stored unused for two years in Murrell’s mother’s garden, was taken away by the police while they dug up the Murell-Sturgeon garden. And we know that more than £600,000 was raised by the party, ostensibly to fund a new campaign for independence that never took place. Where did the money go? No other use of the funds has been made public (although it might be argued that the existence of the SNP is itself a campaign for independence, a line which might be used in a future legal action). Much else remains unknown, suspected but unpublishable—at least for now.

New: Former SNP treasurer Colin Beattie speaking to reporters at Holyrood today:

— Andy Philip (@andydphilip) April 25, 2023

- 'didn't know' about campervan purchase

- SNP is a 'going concern', not in the red.

And in an unusual twist... being under artillery fire in Beirut 'was worse' experience than police investigation.

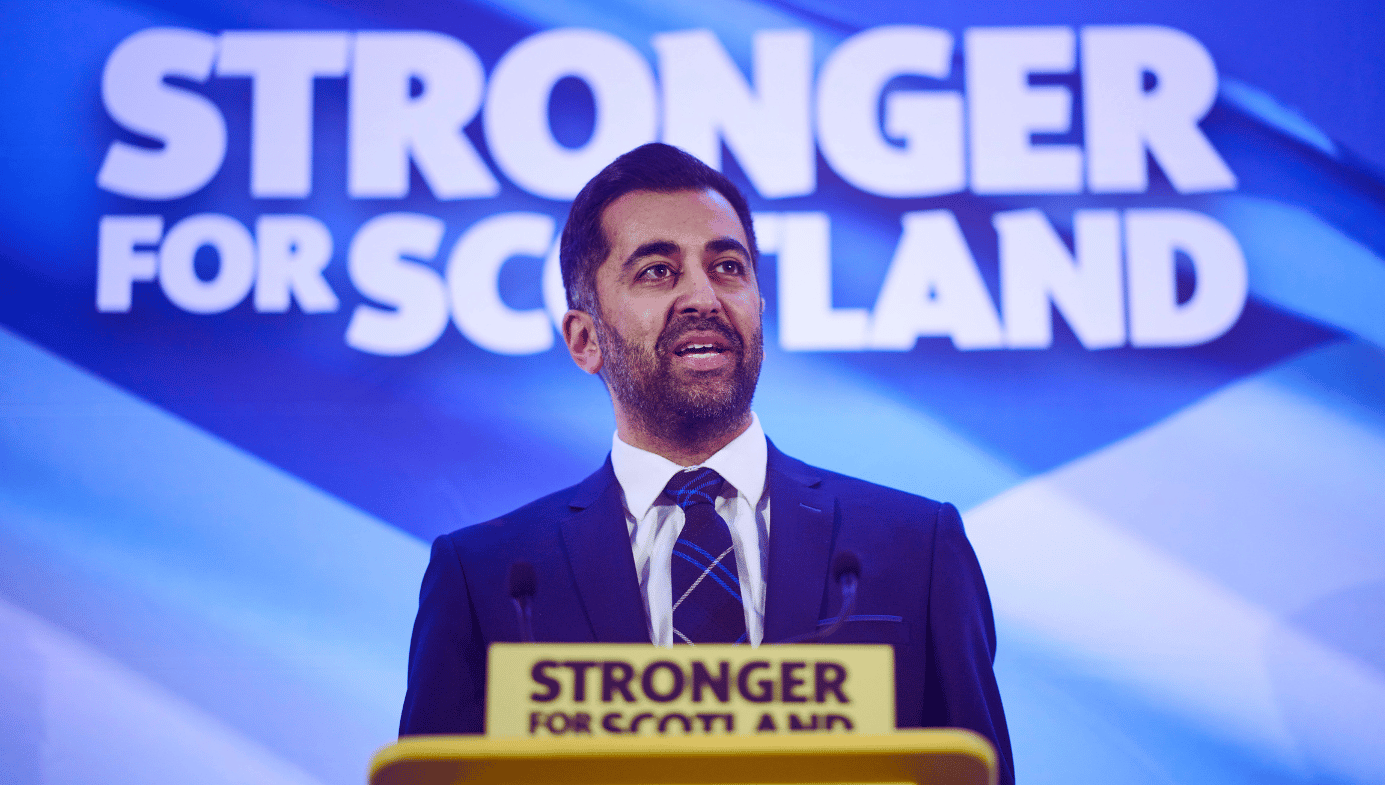

Sturgeon was replaced as party leader and First Minister by Humza Yousaf—the former Justice Secretary, Transport Secretary, and Health Secretary. Yousaf is a close associate of Sturgeon and was her chosen successor, but he cannot offer the evangelical fervour and inner-party thuggery so capably displayed his two predecessors. I spoke—off the record—to several longtime SNP members, and they all despaired of his leadership even as they affirmed their continued adherence to the party and its main goal.

On Tuesday, Yousaf attempted to change the subject with a rousing speech—his first as leader in the Parliament. But before he made it to the safety of the chamber, he was mobbed by journalists who ignored the expected substance of his address in favour of questions about corruption, criminal charges, sackings, falling membership, and support for independence. Rather than simply snapping “No comment” as his predecessors would have done, Yousaf gave a flailing response that was immediately represented as “weak”—a view now shared by a plurality of Scots. His speech turned out to be unremarkable in any case, largely delaying unpopular or expensive policies, and he left the chamber having changed nothing.

Many Scots parliamentarians who voted for one of the other two SNP leadership candidates now argue that Sturgeon’s patronage would have been a liability for Yousaf had the vote been held after her resignation, and especially after the cascade of legal problems. They speculate that Kate Forbes, the former Financial Secretary and the contest’s narrow loser (with 23,890 votes to Yousaf’s 26,032), would have won instead.

If Yousaf is deposed and Forbes installed in his place, a route for salvation might open up that has reverberations beyond Scotland. It all depends on Forbes, who is a politician with the rare ability to shift perceptions and policies. She is young, telegenic, highly educated (a BA and an MSc in history), recently married, and has just given birth to her first child. She is also a member of the Scottish Free Presbyterian Church, familiarly known as the Wee Frees, a 19th-century splinter from the Church of Scotland, which cleaves to an absolute faith in the gospels. Her faith demands the most rigorous moral standards of its adherents, and it is now gaining members, unlike the much more liberal Church of Scotland.

In Forbes’s fundamentalist church, there can be no sex before marriage, no countenancing of abortion, no recognition of the equality of homosexuals with heterosexuals, and no approval of transitioning from one gender to another. In short, Forbes would likely brook no acceptance of practices and tolerations which have become part of the British liberal consensus. Indeed, over the past few years, it has become clear that robust disapproval of any of these positions can attract police attention in the UK and even charges.

Until now, the SNP has loudly proclaimed its endorsement of all these relatively new attitudes, most controversially pledging to make gender transitioning easier. Many MSPs are, like Sturgeon, devotees of the new forms of liberalism and suspicious of religion’s claims. That was why they opposed Forbes. She was frank about her religious beliefs and commitments during her leadership campaign, and parliamentarians and party members worried that, as leader, she would not be able to separate policy from faith.

For her part, Forbes insisted that she would not seek to change her party’s policies on abortion and equality, even though she believes contemporary sexual ethics to be abominations. In this respect, she is in a similar position to Yousaf, whose Muslim faith is scarcely less conservative than that of the Wee Frees. That is, no doubt, why he absented himself from the parliamentary vote on gender identity. But perhaps due to his status as a member of an ethnic minority, Yousaf’s religious principles were not subject to the same scrutiny as those of Forbes during the SNP leadership campaign.

During that campaign, Forbes was scathing about Humza’s failures in his ministerial posts. More guardedly—but still unmistakably—she insisted that independence would be financially dicey and that business enterprise (in which Sturgeon had shown little interest) would have to be nurtured if Scotland wanted to gamble on independence. Only this, she maintained, would allow the country to return to—let alone surpass—the standard of living that large UK subsidies have allowed it to enjoy.

Forbes seems to believe that independence is a way to break with a kind of politics that treats voters as consumers in need of constant reassurance. Instead, they must be treated as citizens required to make informed choices and—in the event of independence—commit themselves to the hard work and thought needed to create a new kind of public life. This, in turn, would ensure that things would, in time, improve.

Forbes has the will to tell her party that it can use the powers of governance to convince voters to support the central economic, political, and moral questions of our time. She understands the need to involve Scots—nationalists and unionists alike—in working through these questions. She could bring people from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland into the debate, setting an example of open politics that recognises the smallness of Scotland’s differences with the rest of the UK. She perceives the need for cooperation at a time when fear of the future is high and cannot be calmed by threadbare rhetorical assurances that all is well when it is not.

That would be a model from which others could learn. And if it ended without a majority for independence, but with new relationships in these islands—well, it might mean that the Scots delivered a new kind of enlightenment, from which all could benefit. An outcome like that would be more important to the lives of ordinary people than more of the same under a new flag.