Education

The Stanford Rape Hoax

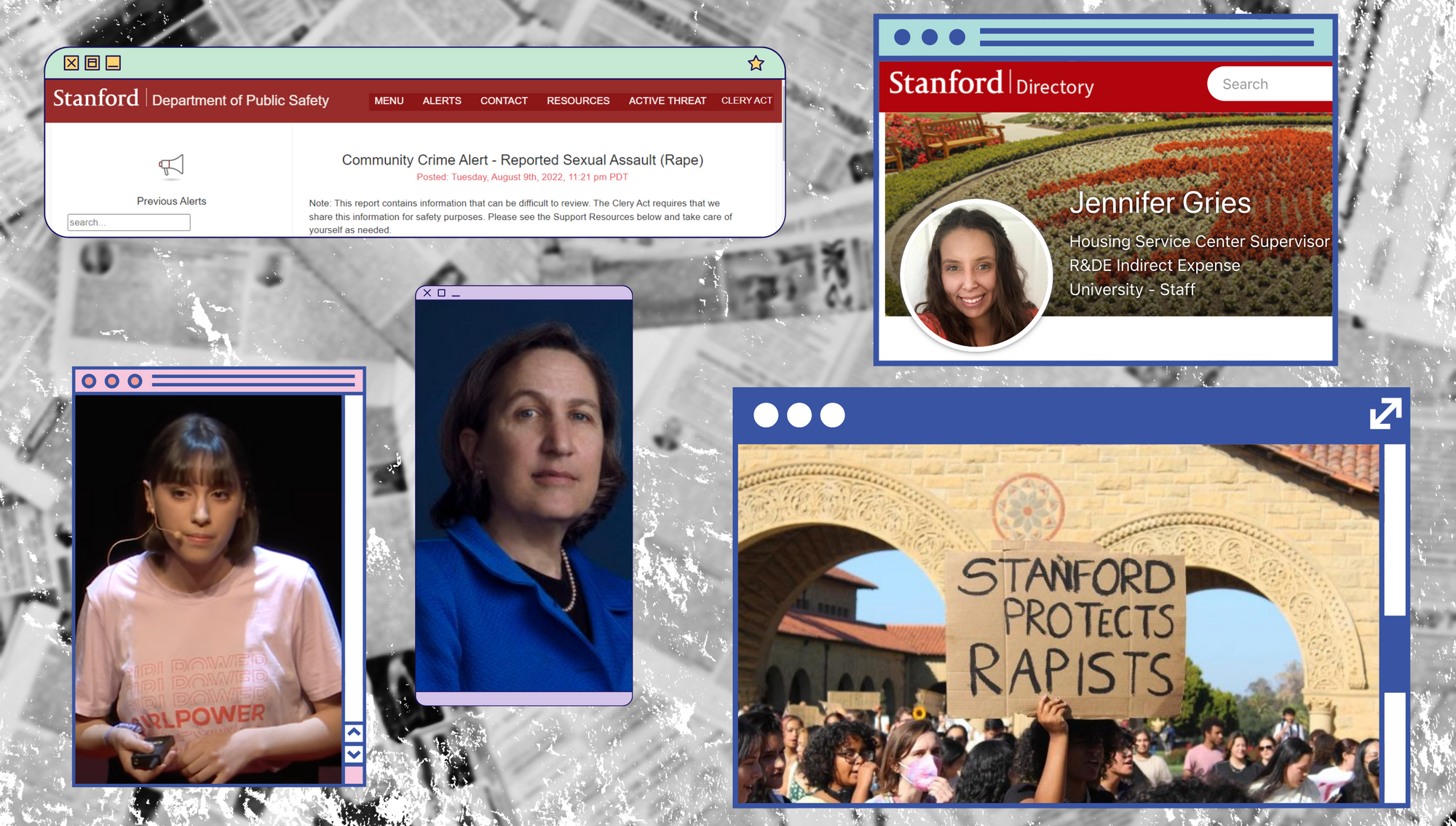

Jennifer Gries used claims of rape to punish a co-worker. Activists at Stanford used her lies for their own purposes.

Jennifer Ann Gries, a 25-year-old housing-services supervisor at California’s Stanford University, appears to lack the critical-thinking skills and good judgement demanded by her job description. For some reason, she was surprised when her claims of being forcibly raped on-campus drew a lot of attention.

Inept as she was, she nevertheless managed to create a climate of fear among the students that exacerbated their hostility to campus administrators, while the university paid out over $300,000 in investigation and security costs. Stanford activists, meanwhile, used the rape scare—both when Gries’s claims were believed to be genuine, and even when they were proven to be false—to advance their own agendas. Their actions reveal a great deal about the state of sexual politics at one of the United States’ most prestigious universities.

The first rape claim

On August 9th last year, Gries went to the Santa Clara Valley Medical Center near the university and claimed that “she was raped by an unknown assailant” at the student-residence complex where she worked. (Unless stated otherwise, all quotes and descriptions of Gries’s allegations and the investigations into them are taken from the Statement of Facts I obtained from the Santa Clara District Attorney’s office). Gries reported that a black male grabbed her in the Wilbur Hall parking garage and told her not to scream. She alleged that he then took her to a nearby bathroom and raped her.

The Valley Medical Center is staffed with nurses who are trained to assist and examine victims of sexual assault. It was at this same hospital that Chanel Miller, then aged 22, awoke under the fluorescent lights early one morning in January 2015, not knowing where she was. She learned that two male graduate students had intervened and grabbed a Stanford student who was dry humping her as she lay passed-out on the ground outside a fraternity house party.

In Know My Name, her New York Times bestselling memoir, Miller described the “surreal” experience of the forensic exam which followed. “How nuts was that?” she later exclaimed to her sister. “They stuck so much stuff into my hoo-hoo. I can’t even…” In addition to the physical exam and the repetitive interviews, there is a lot of paperwork involved in investigating sexual assault. “A stack of papers were set in front of me,” Miller recalled. “My arm snaked out of the blankets to sign. If they explained what I was consenting to, it was lost on me. Papers and papers, all different colors, light purple, yellow, tangerine.”

Following her exam, Miller was interviewed by a detective from the Stanford Department of Public Safety (DPS), the police force in-all-but-name for the university. Unlike Miller, who was a campus visitor, Jennifer Gries was an employee of Stanford. She claimed to have been vaginally and anally raped and subjected to coercion, so she must have been examined for scratches and signs of bruising as well as sexual assault. But she initially declined to speak to the DPS, as was her right.

If Jennifer Gries understood the meaning of the word “perjury,” it did not prevent her from putting her name to an application for a payout from the California Crime Victim Compensation Board. She was eligible for up to $70,000. Her reluctance to speak to the DPS notwithstanding, Gries wanted her claim of violent rape by a stranger to be investigated. It was her “plan,” she told a friend by text message, to make life “a living hell” for a certain male co-worker. So she signed her name to acknowledge that she understood the nurses were obliged to report the assault.

Once notified, the Stanford DPS was in turn obligated by the Clery Act to notify the 36,500 staff, faculty, and students that an adult female had reported being raped by an adult male near Wilbur Hall.

Local media covering the story contacted Stanford Law Professor Michele Dauber for comment. Dauber had recently spearheaded a successful drive to recall Judge Aaron Persky after he gave Brock Turner, the student who assaulted Chanel Miller, a six-month sentence, of which Turner served three. Dauber declined to comment on the new rape report but she did observe that, “Forty-three percent of our female undergraduate students experience sexual violence during their time at Stanford, and the number is highest for freshmen.”

That alarming assertion was allowed to pass unchallenged, but Heather Mac Donald debunked the allegedly astronomic rates of campus rape in an article for City Journal back in 2008. Statistics of this kind depend on the definition of sexual assault used, but the most disturbing figures circulated by activists ostensibly raising awareness of a campus rape epidemic do violence to common sense. After all, if 43 percent of female undergraduates were really being raped or violently assaulted at Stanford, no parent in their right mind would send their daughter there. But think of young people at the height of their youthful vitality, living in coed housing, add alcohol; then ask the females if they have experienced any coercive, non-consensual, or unwanted sexual contact whatsoever over four years, and 43 percent seems like an underestimate.

After Gries’s rape claim, the Stanford community received more emails from university staff, trying to reassure everyone but also acknowledging that they had no more information to divulge. A week later, Gries revealed to DPS that she had seen her attacker on campus before. The DPS investigator urged Gries to name her assailant, both to reassure the Stanford community and to remove the cloud of suspicion hanging over other black men on campus. As one graduate student commented on the student paper website: “I am the only Ph.D Black male student in my department. When I read this story in August, I was afraid that my colleagues and professors would take a second look at me. I had to look over my shoulder.” But Gries refused to provide the name of her alleged assailant. She would only give a description and insist that the public was not in danger.

Title IX and other discontents

Stanford DPS beefed up security on the 8,180-acre campus. An editorial in the student newspaper, the Daily Stanford, reported that the university’s social-media app, Fizz, was alive with outrage. The author, undergraduate Diya Sabharwal, wrote: “The reported rape from Aug. 9 felt like a last straw for me, catalyzing me to write this article and express my anxiety after a summer of learning to numb my senses.” She then turned to her main topic: under-reported sexual assault on campus. “The truth is that many more assaults happen than are ever reported.” Stanford now found itself fielding anxious queries from the parents of students.

Criticism of the university was led by Sexual Violence Free Stanford (SVFree), a student group whose activities often brought them into conflict with university authorities. One of the group’s leaders is Sofia Scarlat, who has been a high-profile feminist activist since her teen years. Scarlat was a freshman when she went to Stanford Hospital for medical care in 2021. She reported that a male student offered to escort her home from a party, but instead took her to his dorm room and forced himself on her. She says she waited for five hours in the emergency department, then gave up and left because there was no special nurse on duty and not even adequate privacy to discuss what had happened to her. She decided not to file a complaint with the university or the police, fearing the emotional trauma of the process.

Following that experience, Scarlat focused her energies on attacking the university. SVFree’s chief issue in 2021 was a tough new alcohol and drug policy on campus intended to curb bingeing and underage drinking. Activists worried that students coming forward to report sexual assault in the context of alcohol abuse would be deterred by the risk of disciplinary action or expulsion. At a convocation ceremony that September, SVFree had hoisted a large banner upon which the words “Stanford Protects Rapists” were emblazoned in red paint.

“Stanford Protects Rapists”: Students protest new drug and alcohol policy at Sophomore Convocation https://t.co/KRVrGKY7Qo

— Ruth Starkman @[email protected] (@ruthstarkman) September 20, 2021

In the end, Stanford officials capitulated and revised the policy: “Should a sexual assault victim report an assault, any ongoing alcohol violation process will be halted; and if a process has been completed, any finding or consequences will be rescinded.” It remains to be seen whether incentivizing claims of sexual assault to avoid expulsion from the third-ranked university in the nation will have any effect on campus crime statistics. Of course, the administrators did wonder if they were creating such an incentive. Dauber, who also pressed for revisions, waved the concern away: “This is based on a rape myth, that women lie about rape.”

It should be noted that SVFree do not dismiss attempts to educate undergraduates about abusive relationships and risky situations as “victim-blaming.” They advocate preventative measures and demand that the university implement a training program called Flip the Script, which teaches students self-defence techniques and asks them to examine their own feelings and actions. There is impressive evidence that this actually works, and the program has been offered on a limited basis at Stanford. But the COVID years interrupted the ability of its Canadian designers to train those who implement the program.

University counsellors and mediators frequently find themselves dealing with tangled issues of sex, consent, and relationships. Advocates for due process have long criticized the use of Title IX, originally created to protect civil rights, as a non-judicial vehicle for adjudicating sexual misconduct complaints. Interestingly, 43 percent of male undergraduates think the university would conduct a “fair” investigation, while only 29 percent of female undergraduates think so, even though the architects of the process were openly biased against accused males.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) revealed in 2011 that the training material for “Stanford jurors” claimed that if the accused was “act[ing] persuasive and logical,” that was a sign of guilt and “they should be ‘very, very cautious in accepting a man’s claim that he has been wrongly accused of abuse or violence.’” When new regulations were mandated in 2020, Dauber argued that complainants should not be subjected to cross-examination by a representative of the accused. “Students routinely said that it was the high burden of proof and cross-examination that most intimidated them away from trying to get accountability.”

Dauber has proposed the following thought experiment: suppose that 40 percent of the undergraduates were stabbed at their time at Stanford, and administrators wanted to know the size of the puncture, or asked the victim why weren’t they wearing a thicker coat. However, the analogy falls apart since administrators wouldn’t be asked to rule on whether the victim consented to be stabbed. It is one thing for Professor Dauber and SVFree—explicitly set up by and for survivors of campus assault—to presumptively assume the guilt of the accused and to advocate for their agenda. It is quite another thing for the Title IX process to be tilted against the accused.

Even after federal revisions to the policy, bias is still evident. FIRE notes that Stanford still does not extend an explicit presumption of innocence to accused students. The handout explaining the Title IX process is written for accusers, not for the accused. And although it’s probably just an unfortunate oversight, a number of the links on the section of the Stanford Title IX website offering “Help for accused students” direct browsers to blank pages.

The second rape claim

None of this, strictly speaking, has anything to do with the Jennifer Gries hoax, except that Gries’s claims, while alarming the students and drawing widespread attention, actually worked against the efforts of campus activists to draw attention to acquaintance rape as a crime that is no less heinous than stranger rape.

Gries believed the co-worker she targeted for punishment had led her on with “false intentions.” In other words, she believed that he was interested in her, and she was disappointed and angry when she discovered that he was not. In March 2022, Gries retaliated with a complaint of sexual harassment against him. Her claim was dismissed as unsubstantiated and Gries was reassigned to work in a different area, away from the accused.

After the HR complaint was set aside, Gries moved on to her first false rape charge. When the DPS failed to arrest her co-worker based on her description, Gries repeated the performance on Friday, October 7th. This time, she went to a different hospital (Stanford Hospital) and spoke to a different nurse. She alleged that a black man had entered her office and dragged her down to the basement where he raped her vaginally and anally in a storage closet. She was examined and swabbed and again she was informed that her nurse was obliged to report the crime to the authorities. Again, she applied for crime-victim compensation funds and again she refused to provide a statement to the police.

Stanford officials responded to the second report with a campus-wide email explaining that they had no further details. Rather than risk any implication that they were blaming the victim for not speaking up, the message went on:

There are a variety of reasons why a victim may not disclose information about a crime. Many victims need time to process what occurred; for some, the trauma of a crime impacts their ability to recall information. Currently, the victim who reported being assaulted yesterday has chosen not to share information about the crime with the police at this time. This also remains the case for the August report, which remains under investigation.

The imperative to validate the victim gave Gries a convenient cover for remaining silent. Dauber attributed the victim’s silence to the failings of her university: “Stanford has consistently failed to hold perpetrators accountable for these kinds of offences, and that has led to the complete collapse of trust by survivors.” But no explanation would placate the Daily Stanford’s opinion-page editor, Joyce Chen. Itemizing a litany of Stanford’s “continual failures” to deal adequately with sexual assault, Chen alleged that the university “chooses to shirk blame and silence our anger.” The spectre of a rapist on campus, she added, was “terrifying and extremely traumatic,” and her university was placing the onus on the victim and leaving vulnerable students to protect themselves with pepper spray.

“Stanford University, accomplice to rape,” and more chants rang throughout Friday afternoon, as scores of protestors charged Main Quad with demands for accountability and action from the administration. The protest follows a string of recent reports of sexual violence on campus. pic.twitter.com/CVQHEYovLb

— The Stanford Daily (@StanfordDaily) October 14, 2022

Stranger rape is comparatively rare on university campuses. In a 2017 essay for the women’s website Verily, Ashley McGuire reported that “82 percent of reported on-campus rapes” in 2014 “happened in student housing.” When asked by the local NBC affiliate to comment on the second stranger rape on campus in three months, Professor Dauber and an SVFree activist instead used the opportunity to talk about the reluctance of students to come forward to report sexual assault.

Dauber noted that the rate of student reporting at Stanford was lower than the national average, while SVFree’s Eva Jones remarked that, “The first thing [Stanford] can do is start improving their relations with reporting and fixing their abysmal Title IX reporting process.” Neither was asked what the Title IX reporting process had to do with an anonymous rapist who, if caught, would surely be booked into the county jail, not scheduled for a Title IX hearing. Dauber only touched on the stranger rape to tell a local news program that the university needed to install better safety measures such as security cameras and panic buttons. “Stanford offices typically have only one door, so it is easy to trap an individual.”

Given how activists speak about Title IX, it is perhaps unsurprising that a majority of female undergraduates surveyed in 2019 reported that they don’t trust the process or its outcomes. Scarlat has described the process as “excruciating” and declined to use it, which allowed her alleged abuser to go unpunished. She did, however, detail her experience in a lengthy essay for the student newspaper last October, in which she was able to present her version of events (without naming her alleged attacker) uncontested. She did so, she wrote, in response to “[T]he horrific acts of rape … such as Friday’s assault or the previous one reported in Wilbur parking lot in August.”

Gries’s claims now allowed Scarlat to accuse Stanford of retraumatizing its own students and condoning rape: “Stanford has created a structure in which, at every step of the way, you as a student and as a survivor stand absolutely no chance against the institution’s power, influence, and desire to hold onto both of those things at the expense of students’ lives.” Scarlat and her SVFree cohorts promptly organized a protest march and rally which prominently featured the slogan “Stanford Protects Rapists,” which the activists had used since at least 2016, six years earlier.

Media reports that the protest occurred “in the wake of” the second alleged rape left the impression that students were accusing their university of protecting the unknown rapist, perhaps through a lack of diligence. But an episode of the Stanford Daily podcast featuring excerpts of the rally speeches reveals a different agenda, and it was not to show solidarity with the then-unknown victim or other victims of stranger rapes. One speaker actually accused Stanford of using the rapes to distract students from the reality that such attacks by strangers were rare:

Most rapists on this campus are raping people that they know, people that they keep going to class with, people that they see at protests, see in frat parties, and obviously Stanford doesn’t want anybody to think about any of that, which is why they are using the recent rapes that are feeding into the “stranger rapist” idea to kind of just push this under the curtain.

In fairness to SVFree, the protest was an “open mic" event so the organizers might not have endorsed all the opinions expressed or agreed that they were strategically helpful. As for demanding more police resources to catch the rapist, the speakers declared (to loud chants of “Fuck the police!”) that law enforcement were part of the problem. “I’m an international student from Turkey,” one speaker announced, referring to the increased police presence on campus. “[T]hey’re fucking everywhere. Not only do I hate cops, I have very personal experience with police brutality, as a queer person, as a feminist. … It’s literally our trauma [that] is being put in our faces every time we see them.”

“Let it be known,” another speaker declaimed, “that [campus] security will not stop the existing 40 percent of undergraduate women-identifying students from being assaulted in their four years … and it is not the solution to ending sexual assault on our campus.” Expel rapists! the students chanted. Fire rapists! Expel cops! Protect survivors!

“We encourage victims of sexual violence to come forward.”

At the rally, Scarlat repeated the message of her Daily Stanford editorial. Stanford officials, she said, always encourage students to “lean on the resources that Stanford has made available to them because they’re there.” (This brought a chorus of boos and jeers from the protestors.) She continued:

[T]hose resources are not only inadequate but they are built in a way to discourage survivors and to enact further violence upon them, to retraumatize. … So I urge you not to believe the statements the university [has] made because the reality is that once you become a survivor here, there is nothing that Stanford does to actually protect you. Their image and their reputation and the future of your rapist will always come first and that needs to change.

By “the future of your rapist,” Scarlat was referring to the fact that students found responsible for sexual misconduct are suspended for varying periods of time, or moved to different housing. A few withdraw from Stanford voluntarily, but according to SVFree, only two students have ever been expelled. Although the Stanford DPS does pass cases on to the DA’s office for review, the DA (with the notable exception of the Brock Turner case) declines to prosecute. “Prosecutors can be particularly cagey about going after sex assailants in the university setting, where assaults often involve alcohol and take place between acquaintances at parties rather than ‘stranger danger in the bushes,’” Dauber told the Palo Alto Daily Post in 2019.

Now there did appear to be a “stranger danger in the bushes” threat at Stanford, or at least everyone thought so. But unlike other high-profile rape hoaxes, neither the victim, “an adult female,” nor the supposed rapist, a black male, could conveniently advance a larger narrative. In the 2006 Duke Lacrosse case, the falsely accused were athletes, and in a now-discredited 2014 Rolling Stone article, a female student claimed to have been gang-raped at a fraternity. Varsity athletes and campus fraternities are low-hanging fruit for advocates concerned about “rape culture” on campus.

In a letter to Judge Persky concerning Brock Turner’s sentence, Dauber (quoted here) claimed that, “students who have committed sexual assault at Stanford ‘typically have participated in athletics.’” Dauber has said that she would like to see fraternities eliminated nationwide, noting on her Twitter account: “One federal study found that if a female undergraduate attends 1 frat party per month it raises her odds of being raped by 38 percent.” (Dauber has since deleted her Twitter account, possibly as a result of the backlash she received for some intemperate tweets about the Amber Heard/Johnny Depp trial, during which she was an ardent supporter of Heard and made disparaging remarks about Depp’s female attorney.)

As campus activists continued to vent their anger at university officials, Stanford spokesmen could only reiterate that they cared about victims of sexual violence: “Our fervent, continuing goal is to provide care and support for survivors of sexual violence at Stanford, to hold perpetrators of sexual violence accountable, and to ensure a safe campus community that is free of violence.” The university also urged “anyone who may have information related to [the second rape claim] to share it with the Department of Public Safety.”

And in fact, an important witness did come forward to provide the information that dealt the final blow to Gries’s credibility. Investigators learned that at the time of Gries’s HR complaint against her co-worker, she had told a friend that he had impregnated her with twins but that she had miscarried. Medical records revealed this to be a lie and Gries was confirmed as a fabulist. This was the same friend to whom Gries confided that she was “coming up with a plan.” Gries told her that she was going to “stand up for myself” and punish her co-worker so he would be “shitting his pants for multiple days.”

In early November, a detective from DPS asked Gries if the man she had named in the human resources complaint was her attacker, and warned her that they would speak to anyone who knew both Gries and her colleague. In response, Gries began to cry and hyperventilate. She broke off the interview, later claiming that she had to go to the emergency department.

Gries’s target duly provided his whereabouts at the times of the two alleged assaults and told investigators that his relationship with Gries had never been sexual. He added that the HR process “scarred” him and “caused him extreme stress during a time when he was caring for his gravely ill mother, who later passed away.” “This is disgusting,” he said of the ordeal Gries had put him through. “I don’t feel human. I don’t feel human at all.” He must have known, perhaps even as early as August 9th, that Gries was trying to implicate him in a violent rape, but he was not vindicated for nine months.

“A sensitive and difficult matter”

On January 24th, 2023, Gries finally admitted that she had made everything up. But she was not arrested until mid-March, when it was reported that she had “been charged with two felony counts of perjury and two misdemeanor counts of knowingly inducing another person to give false testimony pertaining to a crime.” The reasons for the delay may never come to light and may be purely procedural. However, both the Santa Clara District Attorney and the university were clearly concerned that charging Gries would send the wrong message. “Our hearts go out to legitimate sexual assault victims who wonder if they will be believed,” said DA Jeff Rosen in his statement announcing the arrest.

The general public was not about to protest the arrest of a woman for making false claims, but Rosen must have realized that he’d receive criticism from one particular quarter. Dauber publicly questioned Rosen’s “judgment” in charging Gries, and said she was especially concerned that Rosen’s office had disclosed that Gries’s rape-kit test results had found no male DNA and were therefore “not consistent with her story.” “[T]he publicity about those charges … will chill victims from seeking forensic medical exams,” she said. In a campus-wide email, university officials were evidently uneasy about raising the “sensitive and difficult matter” that a woman had lied about being raped, emphasizing that false claims of rape were “extremely rare,” while sexual assault remained “prevalent both at Stanford and in our broader society.”

Advocates who understand the value of using statistics to make their arguments—one-in-five, one-in-four, 40 percent—speak of the “chilling effect” as a truth universally acknowledged, not as a statistic. Dauber might take some reassurance from the 2019 Stanford student survey which revealed that when female students who experienced coercive sexual contact were asked why they didn’t come forward for help, only 8.4 percent chose “I didn’t think anyone would believe me” as a reason, while 53.3 percent chose “I could handle it myself,” and 54.2 percent said their experience wasn’t that serious. (Students could choose multiple reasons from a dozen choices, including “other.”)

On March 15th, the same day that Gries was arrested, the Daily Stanford published an opinion piece co-authored by Stanford alumna Dr. Jennifer Freyd. Freyd exploited the publicity around the rape scare—at the very moment it was being discredited—to add her support to the campaign against Stanford for its “institutional betrayal.” She had visited the campus on previous occasions to give presentations of her research into precisely this topic. In the eyes of the Stanford activists, the university was failing to acknowledge the gravity of the sexual-assault crisis on campus and offering insufficient support and validation to students who experienced or claimed to have experienced sexual assault. While changing male attitudes and behavior is certainly one of their end goals, their ire was consistently directed first and foremost at the university administration.

Freyd is well acquainted with the controversy surrounding false accusations. Years ago, she accused her father of sexually abusing her, after she began to experience visions that she interpreted to be repressed memories of molestation. In response, her parents established the False Memory Syndrome Foundation at a time when many parents were being accused of heinous crimes by adult children in “recovered memory” therapy. Freyd has maintained that her memories are authentic; her father has vehemently denied them. A wave of lawsuits would later bring an end to therapeutic confidence in recovered memory therapy.

Freyd is now the founder of The Center for Institutional Courage, an organization dedicated to overcoming institutional betrayal. Ross Cheit, a professor who believes that some defendants in the notorious ritual abuse cases of the 1980s were actually guilty, serves on the board. The motto of the social workers and police detectives, who turned up hundreds of alleged cases of Satanic ritual abuse in a modern-day witch hunt, was “Believe the children.” (I was involved in reporting on the “Satanic panic” and wrote about the cases of accused people, some of whom are still in prison.)

Freyd’s assumption throughout her editorial is that a caring and courageous institution will preemptively assume that all sexual-assault complainants are genuine, and that a failure to do so amounts to a betrayal that worsens their pain and trauma. To question a survivor’s account is to assault her anew. As Christina Hoff Sommers has warned, girls today are being taught a new iteration of feminism on campus: “[A] new trauma-centered feminism has taken hold. Its primary focus is not equality with men—but rather protection from them. This new ethic of fear and fragility is poisonous and debilitating.”

Adopting Freyd’s recommended approach would make a mockery of due process, as a number of readers pointed out below the line. A couple of commenters also noted that she undercut her own argument by referencing Gries’s claims, which had fallen apart on the day her article appeared. It had just been demonstrated, in a way no-one was likely to forget, that women can and do sometimes lie about rape. “It’s a tricky balancing act,” wrote one commenter. “On the one hand, sexual abuse can not be tolerated, and those who are subjected to it deserve justice. On the other hand, the accused deserve due process and an assumption of innocence. Railroading the accused will not help anyone. It’s a pity this article addressed only one side of this.” “Could it be,” asked another, “that Stanford is not intending to shield perpetrators, but instead is just not able to determine who perpetrated what?”

False accusations, feminist activists insist, are so vanishingly rare that they do not merit meaningful consideration. In fact, the true number of false accusations is difficult to determine, since not every accusation is tested in a court of law. Dauber did at least allow that the “allegations” against Gries were “troubling,” but Sofia Scarlat was evidently not in the mood for a rethink. Instead, she reacted to Gries’s arrest by flinging another bad-faith accusation at her university, asking students to “think critically about how Stanford might use this scenario … to protect Stanford as a school rather than protect survivors.”

SVFree also seized upon the word “allegation” to describe an accusation that has been made but not proven, although it is unlikely that they will make a habit of drawing attention to this distinction in future. They posted a statement on Instagram after Gries’s arrest, calling her attempts to incriminate an innocent man in a heinous crime “an unfounded allegation” and defensively explaining that their October protest was not specifically related to the rape panic Gries had caused, but was “a protest against Stanford’s institutional betrayal of survivors. … We reassert our demands for … the immediate removal of students and staff found responsible for sexual assault from campus.”

Aye, there’s the rub. What is meant by “found responsible”? Who makes the finding? How is that finding made, especially if students boycott the Title IX process? Does it require more than an allegation, especially since SVFree’s statement reaffirms that the organisation “will continue to, and always, believe survivors”? It seems that just as Stanford’s law students have difficulty with free speech, Stanford’s anti-rape activists still have problems with due process.