Politics

Beyond Davos

If the Davos crowd has demonstrated anything, it is the futility of their posturing.

Few annual events produce more paranoid commentary than the World Economic Forum’s recently completed Davos conference. The WEF, founded in 1971, has not only become the favored target of lunatic spinmeisters like Alex Jones and right-wing zealots like Glenn Beck but also of Fox News and many conservative activists. It is widely regarded as the place where a terrifying “Great Reset” has been plotted by the mighty—a plan hatched behind closed doors between sips of champagne and forays onto the slopes. The South African reporter Lara Logan even claimed (falsely) that the new Speaker of the House, Kevin McCarthy, was selected at Davos.

“WEF is a sitting target (of misinformation)—very expensive to attend, invitation only,” said Claire Wardle, co-director of the Information Futures Lab at Brown University. “It’s playing out the foundation of every conspiracy theory, which is that the world is being controlled by a secret elite and you’re not part of it.” But suspicions like these misunderstand the problem. A transformation of the world economy is occurring, but not because a bunch of elite business, political, and media folk preen on stage while enjoying Swiss comforts. Rather, the world is changing because the tectonic plates governing economics and politics have moved, and they are likely to continue moving.

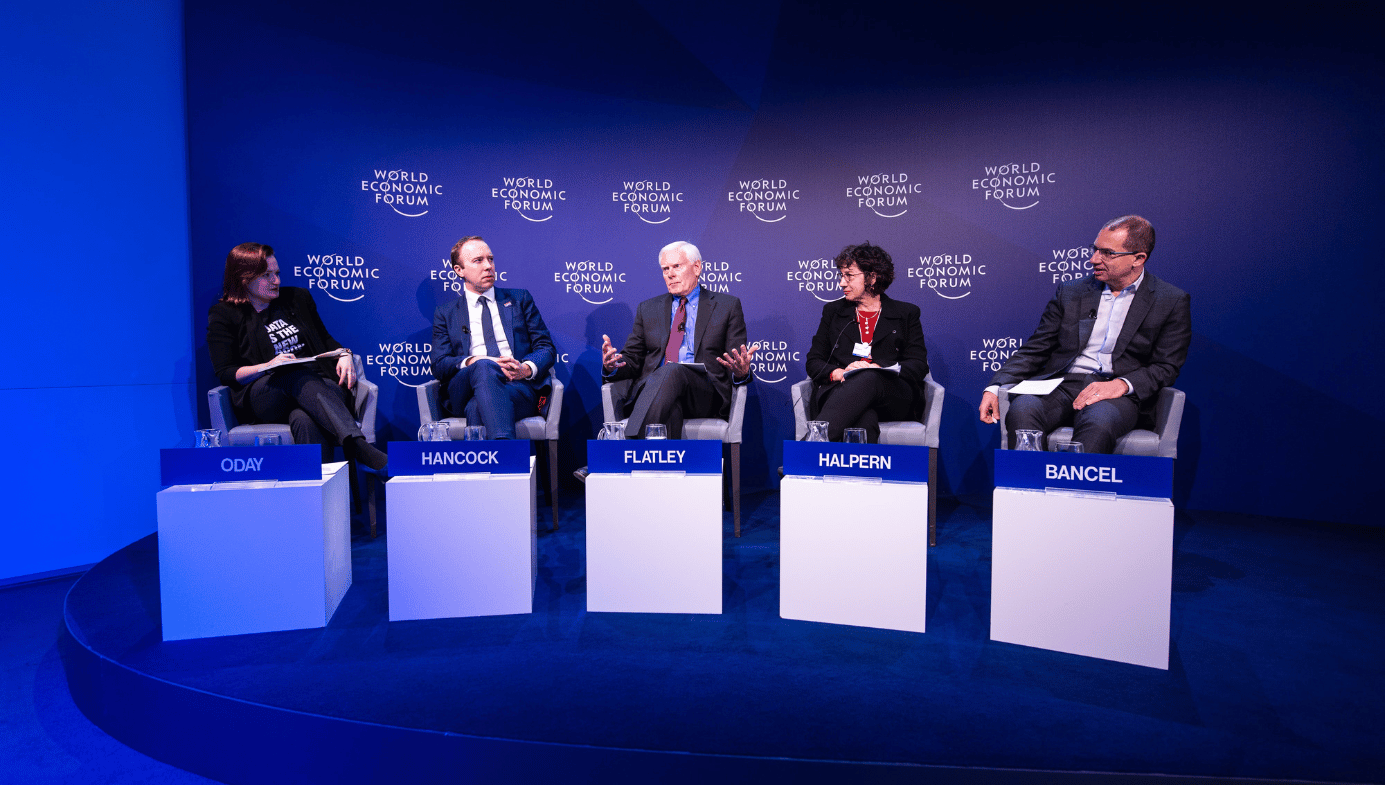

The establishment avatar

The populist conspiracy theorists mistake showmanship for reality. Cambridge legal professor Antara Haldar notes that Davos is not really a place where important decisions are taken. It represents a symbolic “avatar” for the elites. If the Davos crowd has demonstrated anything, it is the futility of their posturing. They lack the ability to influence the leaders of countries like India and China, much less places like Iran, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Some of the leaders of these countries may speak and consort with the Davos crowd, but they clearly do not listen to them. Nor do the West’s middle classes, who are proving reluctant to embrace an environmental agenda that threatens immiseration.

The WEF is unable to affect the global future outside the narrow confines of their own gilded circles. “On its face, Davos appears to be a meeting out of touch with the times, focused more on privilege than social change, economic displacement, or cross-cutting global challenges,” noted the Brookings Institution in 2020. Rather than an expression of real power, Davos reflects the continued rise of the publicity-mad business leader, first identified by Daniel Bell a half-century ago. Prior generations of business had embraced Western culture and national identity and placed some priority on addressing the needs of larger society. The new corporate elite, however, is unmoored from religion and family and this is transforming the foundations of middle-class culture.

More than anything, Davos demonstrates not power—it has no legislative or regulatory power—but the relentless search for prestige and recognition. It is no more real in its effects than a Kabuki play.

Aristocracy redux

The elites gathered at Davos may spout progressive ideas, but they actually represent something more like a return to the kind of hierarchy associated with feudalism. After nearly a half-century of expanded social mobility, Western economies have become increasingly stratified, with economic power concentrated in ever fewer hands. In the past decade, the proportion of US real estate wealth held by middle- and working-class owners fell substantially. “In 2010,” reports the Wall Street Journal, “high-income homeowners held 28% of all U.S. housing wealth. By 2020, that figure rose to 42.6%.” In the last decade, “about 71% of the increase in housing wealth was gained by high-income households, according to a report released Wednesday by the National Association of Realtors.”

This is a global phenomenon. Housing prices have risen “three times faster than household median income over the last two decades,” according to the OECD. And housing, it finds, “has been the main driver of rising middle-class expenditure.” In the next generation, those who purchase houses will be doing so through what one writer calls “the funnel of privilege.” Millennials who received bequests inherited more money than many workers make in a lifetime. “Inherited wealth will make a comeback,” predicts the economist Thomas Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Inheritance as a share of GDP in France, he writes, grew from roughly four percent in 1950 to 15 percent in 2010. The growing importance of inherited assets is even more pronounced in Germany, Britain, and the United States.

These trends were evident long before anyone had ever heard of Klaus Schwab. What Davos does—for both the conspiracy nuts and the general public—is provide a garish stage for a bifurcated class structure. In the United States, in recent decades, wealth gains have been concentrated among the top 0.1 percent—roughly 150,000 people. Since the mid-1980s, the share of national wealth held by those below the top 10 percent has fallen by 12 percentage points, the same proportion that the top 0.1 percent gained. A British parliamentary study projects that, by 2030, the top one percent will expand their share to two-thirds of the world’s wealth, with the biggest gains overwhelmingly concentrated in the top 0.01 percent.

Davos did nothing to create this reality, but it has provided a global platform for the two sectors—finance and tech—that dominate the new aristocracy. The movement to impose unprecedented environmental and other strictures would not be so concerning were the financial sector not becoming more concentrated—the number of banks “has declined by more than 2,300 during the past 20 years, with most of this decline happening in the past 10 years.” The five largest banks control over 45 percent of all assets in the US, up from under 30 percent about 20 years ago. Europe has experienced a slower but similar consolidation.

But the real game-changer has been tech. Silicon Valley, once an exemplar of competitive capitalism, is morphing into a Gargantua of giant firms with market power unprecedented in modern times. For example, Google and Apple account for nearly all mobile browsers worldwide, while Microsoft controls 90 percent of all PC operating system software. Three tech firms now account for nearly two-thirds of all online advertising revenues, which comprises the vast majority of all ad sales.

Mike Malone, who has chronicled Silicon Valley over the past quarter-century, believes the industry has lost much of its egalitarian ethos; the new masters of tech, he argues, have shifted from “blue-collar kids to the children of privilege.” “An intensely competitive industry,” he suggests, has become enamored with the allure of “the sure thing” backed by massive capital. If there is a potential competitor, they simply buy it. We can see this clearly in the evolution of artificial intelligence (AI), which, rather than spark a wave of new startups, is now becoming dominated by a few large firms.

Equally worrisome: these mega-tech firms now have a stranglehold on communications and dialogue, even though their stocks have plummeted and layoffs enacted. There is already evidence that AI is being designed with political biases, particularly on climate issues. Other critical spheres, such as cloud services and ownership of underwater fiber-optic cables, have fallen into fewer hands. Like the feudal system, power and knowledge is narrowly concentrated, which bodes ill for innovation but well for the preservation of hierarchy; they have become, notes Michael Lind, the epicenter of “the new corporate tyranny.”

The new clerical class

Like the aristocrats of feudal times, this new ruling class needs the constant approval of the enlightened. In the Middle Ages, this role was played by the Catholic Church, and in the eastern reaches, Orthodoxy. The correlation between the aristocracy and the upper echelons of the Church was intimate, with bishops often living, like the aristocrats, in elaborate castles and enjoying many of the pleasures—notably luxuries and sex—associated with the upper classes.

In the Medieval era, the Church and its educational system worked to eliminate heterodoxy and support the reigning social order. This included promoting poverty and chastity, while encouraging people to send their children to serve in the priesthood or as nuns. This value system, of course, did not govern the behavior of lords and elite prelates, for whom indulgences and prayers could make up for misdeeds.

Today, this role is taken by a secular equivalent that Samuel Taylor Coleridge called “the clerisy”—the inheritors of the role once played by Europe’s clergy. Today’s clerics may lack the coherence or spiritual power of Christianity, but they instruct the masses how to live, nonetheless. This is achieved largely through lavishly supported nonprofits promoting the cultural agenda of the progressive Left, notably on issues of gender and “anti-racism.” But the most powerful commitment has been to the green agenda, promoted with massive donations from the top levels of both corporate and inherited wealth. As Robert Bryce has demonstrated, green non-profits in 2021 received well over four times as much as those advocating for the use of nuclear energy or fossil fuels.

This, too, reprises feudal themes. Just as the aristocrats of the Middle Ages financed elaborate cathedrals, monasteries, and nunneries to promote Christianity and insure themselves against damnation, the massive funding of a green establishment today imposes burdens on the middle and working classes while providing huge opportunities for investment banks. Davos’s greatest accomplishment has arguably been to demonstrate, and celebrate, the merger of these two ascendent classes.

The diminution of the middle class

In the Middle Ages, religion was employed to maintain the social order and dismiss dissenting thoughts, including from within the clergy. In our times, the massive funding of the climate movement plays a similar role, pressing the universities and scribbling classes to adhere to the party line. Although extreme in its consequences, this does nothing to harm—and may even enhance—the power of the ruling class.

At the same time, the current green policies threaten to constrict middle- and working-class aspirations. As the climate movement has grown richer, it has become more puritanical and extreme in its policies. Some see the need for a “climate lockdown” or at least an economic policy that values climate mitigation over all other concerns. No longer can we, as President Obama suggested, use natural gas as a transition fuel or even nuclear power, which has the greatest potential for generating clean energy. Instead, the middle and working classes, must suffer a policy that assures high energy costs and wipes out blue-collar jobs or drives them to other countries.

Although the Davos crowd and their allies across the West talk incessantly about democracy, their agenda can only be imposed in an autocratic manner. Environmentalism accomplished many great things—such as cleaning up air and water pollution—that benefited people in general. But contemporary green policies increasingly see people as the “problem”—it is the lifestyles of the masses that will need to be reined in if we are to “save the planet.” By seeking to squelch future growth, the current drive to “net zero,” as Deutsche Bank’s Eric Heymann has noted, will likely require a “a certain degree of eco-dictatorship” and have catastrophic effects on middle-class living standards.

Certainly, the ambitions of the “Great Reset” embraced at Davos trigger hostility to the liberal global order. Some, such as those examined in historian Tara Zahra’s Against the World, see any rebellion as comparable to ideas that helped spark the rise of fascism a century ago. Policies that enjoin the end of middle-class property ownership are promoted. The slogan “You’ll own nothing. And you’ll be happy”—an idea that led the WEF’s 2016 predictions about 2030—might sound like socialism, but it actually just means that more of the world will be owned by someone else, notably the corporate aristocracy or, perhaps in some places, the state, as is increasingly the case in Europe.

Simply put, the Western middle and working classes are being offered not a better future but permanent propertyless serfdom. Generally, the green approach to housing policy seeks to take people out of their cars and pack them into dense urban areas, where they will become permanent renters. This would be another win for the oligarchy, but a disaster for the middle orders. Roughly three-quarters of Americans, according to one recent study, consider home ownership an essential or critical part of being middle class.

3/ More than 70% of Americans see "being able to support your family on one parent’s income" as "Essential" or "Important" to being in the middle class (men: 73%, women: 69%), which puts it right at the top of the list next to affording health insurance and owning your own home. pic.twitter.com/hyUWiqHFSI

— Oren Cass (@oren_cass) February 15, 2023

The shift from expanded property ownership to rentership is not only proceeding in the United States and even historically egalitarian Australia. In the United Kingdom, “only a third of Millennials own a home, compared with almost two-thirds of Baby Boomers at the same age,” and at least one-third of British millennials are likely to remain renters for life.

A post-Western era?

The optics of the Davos conference might seem to imply the supremacy of the Western elites but they obscure the actual shifts in global power. During the Middle Ages, Europe was largely a backwater, well behind in innovation, power, and culture to China, India, and the Islamic world for the better part of a millennium. To be sure, some leaders in the developing world may attend the conference, and even genuflect towards both the “net zero” and cultural agenda of the progressive West. But in reality, few will adopt these approaches, given their own cultural proclivities and economic needs.

Rather than demonstrating the power of our elites, Davos exposes the growing chasm between them and the developing world. Their ability to shape the world order is clearly in decline. Powerful states like China, Russia, and India, as well as much of Africa, hardly share the gender politics of the West. Russia has again embraced Orthodoxy, along with nationalism, as its raison d’etre, while China seeks to get “sissy men” off television, along with anyone who violates the puritanical edicts of the Communist Party.

But the most consequential break is over green ideology. Restrictions imposed by global institutions like the World Bank on the use of gas, coal, and nuclear power are not widely embraced in the developing world. During the IPCC Glasgow conference, India’s prime minister Narendra Modi said that India will only address climate change by 2070, a remark in line with the Indian Energy Minister’s comment in 2015 that India would resist “Western carbon imperialism.” Pakistan has already announced its own program of rapid fossil-fuel development, centered around coal.

Moves by the European Union to impose carbon taxes on developing country exports—now driving coal consumption to record levels—seem likely to speed the creation of an alternative economy capable of existing outside Europe and North America. The Ukraine war has only widened divisions between Western elites and developing countries. India, most of Latin America, and Africa have avoided the sanctions regime while following China’s lead by embracing state-directed capitalism, using coal and other polluting fuels, and buying Russian raw materials at discounted rates.

Rather than a world reflecting the values celebrated at Davos, we could be seeing the emergence of an alternative order centered more on Moscow, Delhi, Beijing, Lagos, and even Tehran as opposed to New York, London, or Paris, much less Switzerland. As green austerity weakens the West’s economies and their middle orders, China continues to seek to replicate its ancient role at the center of the world, this time by dominating not only goods manufacturing but also such key technologies as solar panels and, perhaps, nuclear power.

Time to stop the clown show

Davos’s high-end clown show may have little longterm effect—except on the fevered minds of conspiracy theorists—due to its utter impracticality. The opposition from the developing world, as well as from large swaths of the domestic middle class, undermines the notion that societies can be easily “reset” as desired. Elites may be happy to see once-advanced economies like that of the UK de-industrialize, but this development may spark opposition from those who still produce goods, grow food, and develop reliable energy systems.

The enlightened plutocrats at Davos may talk planetary austerity for the developing countries and their own middle orders, but they do not want to do without their own luxuries. The hard-pressed classes may be less than willing to put up with this. After all, it’s hard to sign onto an austerity regime urged by people who own numerous properties, private jets, and yachts. This discordance is made worse by the fact that many of the loudest advocates for investment in China, easily the world’s largest polluter, are Davos denizens like Michael Bloomberg and executives from Goldman Sachs.

Davos Man has, Antara Haldar argues, “a people problem”—a lack of “social skills” that bodes ill for him in the long run. Much of the media associates the disaffection this produces with the far-Right, but resentment strengthens populists on both sides of the spectrum. The notion that the world is controlled by a “secretive” elite, notes one recent survey, is embraced by Brexit Party members, left-leaning Scots and Welsh nationalists, and members of the Labour Party. One-third of Conservatives believe in such conspiracies.

But Davos represents more than catnip for conspiracy theorists. It symbolizes broader trends toward a privileged autocracy that people—both in the developed and the developing world—of most political persuasions reject. Rather than rule by unelected bureaucrats and ever more powerful NGOs, people have a natural tendency to see responsibility vested in their elected representatives.

Ultimately, human beings do not readily submit to arbitrary control from the kind of people who gather at Davos, particularly if they are expected to lower their living standards, and those of their offspring, to feudal levels. “Happy the nation whose people have not forgotten how to rebel,” wrote the British historian R.H. Tawney. Whether people in the West or the developing world can muster the will to assert our place as engaged citizens will determine the kind of world our children inherit.