Art and Culture

Getting Fletch Wrong

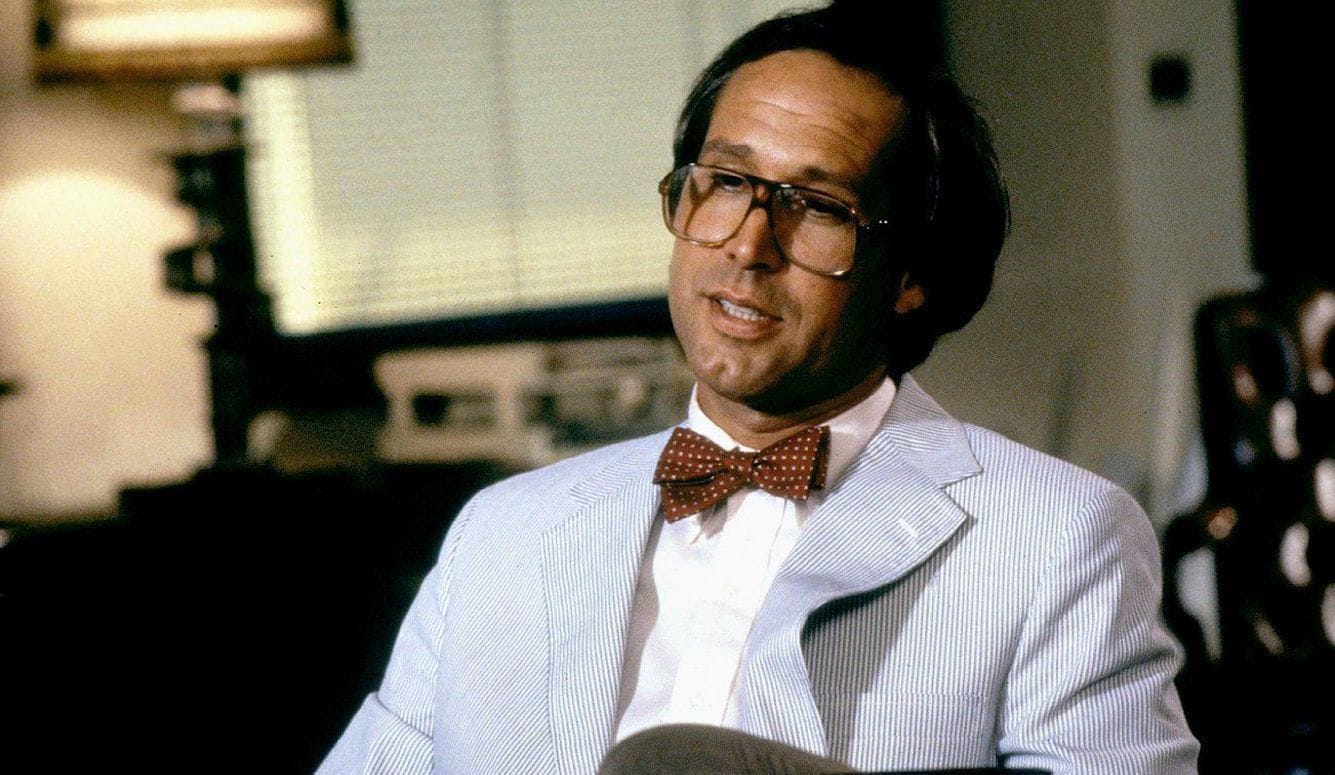

Jon Hamm’s portrayal is an improvement on Chevy Chase’s goofball routine, but still bears little relation to the amoral cad in Gregory McDonald’s novels.

Earlier this month, Miramax brought us Confess, Fletch, the latest cinematic incarnation of the wise-ass investigative reporter first brought to the screen by Chevy Chase and director Michael Ritchie in the 1980s. Ritchie’s 1985 film Fletch is now widely regarded as a cult classic, and in 2008, a group of Los Angeles Times writers voted it the 23rd best film set in Los Angeles over the previous quarter-century, alongside gems like L.A. Confidential, Boogie Nights, The Big Lebowski, and The Player.

In 1999, the New York Post’s Jonathan Foreman reported that Fletch had become all the rage on American college campuses:

“It’s huge,” Chase tells The Post. “I would get calls from colleges like Amherst and Williams when I was back in L.A. a few years ago. And I actually spoke to a [film studies] class at one of those colleges by speaker phone! Here I was, talking to a class of 200 people—and you know, it’s not ‘Lawrence of Arabia.’”

The 1989 sequel (also starring Chase and directed by Ritchie) was not as successful, earning 10 million dollars less at the box office on an identical budget. Nevertheless, it was still reasonably profitable and Universal was eager to make a third film. In the mid-1990s, the studio approached director Kevin Smith to make a threequel, but that effort ended in development hell. When Universal lost the rights to the property, they were scooped up by Miramax in the early 2000s, and Smith was assigned to midwife the project—possibly an origin story starring either Jason Lee or Ben Affleck. It never came to pass, which is a shame; taking Fletch back to his 1970s origins still strikes me as a great idea.

Fletch was the creation of novelist and journalist Gregory McDonald. The son of a CBS Radio newsman, McDonald was born in 1937 and grew up in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, an upscale community about 40 miles west of Boston. After he graduated from Harvard in 1958, McDonald became a schoolteacher for a few years before taking up journalism and spending six years (1966–73) as a staff reporter on the Boston Globe. His start in newspapers roughly coincided with the beginnings of the New Journalism, which employed novelistic devices, outright invention, and first-person stories in which the reporter was an active participant. The best-known practitioners of this form—Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Hunter S. Thompson, Truman Capote, George Plimpton—would all become bestselling authors and avatars of the Nixon-era zeitgeist.

McDonald clearly aspired to join their ranks. He never gained much fame as a journalist, but in 1985, after his mystery novels had become bestsellers, his publisher brought out a collection of his best newspaper stories called The Education of Gregory McDonald. McDonald himself wanted to give it the more gonzo title of “Souvenirs of a Blown World” and when it was republished by a small press years later, that was the name it was given. McDonald’s journalism was less “inventive” than, say, the rantings of Hunter S. Thompson, but it was New Journalism nonetheless. Here are a few of his opening lines:

The night Martin Luther King was shot I rode through the black ghetto in a taxi. I had been told to stay out of the ghetto that night.

and

We were drinking Scotch in milk at a small table in a waterfront dive, soldier Claude Smith and I. He was all pressed and shining in a new uniform, new ribbons, his wounds freshly dressed, these few days before his discharge.

and

It was midnight and we were under an adobe arch beside a swimming pool on a ranch outside Dallas, Texas, and Big John Wayne was wearing his head rug, a loose khaki shirt, and pants pressed like I had never seen pants pressed before—all the way up to his belt in back.

As the son of a traditional reporter, McDonald had a foot in both journalistic camps, the establishment and the gonzo. He admired the conventional reporting of Neil Sheehan at the New York Times, who broke the Pentagon Papers story, and of Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward at the Washington Post, who broke the Watergate scandal. Having failed to transform himself into a cross between Sheehan and Thompson, he decided to invent a character who was just that, named Irwin Maurice Fletcher—“Fletch” to his friends.

The first book in the series, also called Fletch, was published in 1974 by Bobbs-Merrill. The hardback edition was a modest success, but the paperback edition, published the following year by Avon Books, became a phenomenon. This may have had something to do with the paperback’s unusual cover, which reproduced a lightly edited transcript of the book’s opening dialogue:

“What’s your name?”

“Fletch.”

“What’s your full name?”

“Fletcher.”

“What’s your first name?”

“Irwin. Irwin Fletcher. People call me Fletch.”

“Irwin Fletcher, I have a proposition to make to you. I will give you a thousand dollars just for listening to it. If you decide to reject the proposition, you take the thousand dollars, go away, and never tell anyone we talked.”

“Is it criminal?”

“Of course.”

“Fair enough. For a thousand bucks I can listen. What do you want me to do?”

“I want you to murder me.”

Fletch said, “Sure.”

How many lovers of pulp crime fiction could resist an opening like that? The paperback edition sold so well that Avon Books took the unprecedented step of outbidding Bobbs-Merrill for the rights to the book’s sequel. Having made Fletch a pop-cultural juggernaut, Avon didn’t want to wait a year while Bobbs-Merrill reaped the rewards of the sequel’s hardback edition. So, Confess, Fletch was published in 1976 as a paperback original and duly became another huge success. Both books were handed Edgar Awards by the Mystery Writers of America (the former for Best First Novel by an American Author and the latter for Best Paperback Original Novel), the only time that a novel and its immediate sequel won Edgars.

Coincidentally, the same year Bobbs-Merrill published the first of McDonald’s Fletch books, Holt Rinehart and Winston published The Big Kiss-Off of 1944, the first book in a series about the exploits of Private Eye Jack LeVine. That novel was written by Andrew Bergman, who would go on to write the script for the first Fletch film. Bergman’s book got the more auspicious start, earning plaudits from Ross Macdonald and Jack Higgins, but Fletch would win the awards and sell millions of copies. Though he was no Raymond Chandler, Gregory McDonald was capable of writing amusing dialog and quick, striking character sketches. Plus, he was a devious plotter.

Hollywood immediately showed an interest. The film rights to the first novel were purchased in 1974 by a small production company that hoped to partner with Columbia Pictures on an adaptation. After Columbia passed on the idea, an independent producer named Jonathan Burrows acquired the rights and shopped the idea around to nearly every major studio in Hollywood, as well as a bunch of minor ones. At various times, Burt Reynolds, Mick Jagger, Jeff Bridges, Charles Grodin, Richard Dreyfuss, Barry Bostwick, and George Segal were connected with the project. Chevy Chase was also offered the title role, but his agent turned it down without consulting him.

By the time the film finally got made and released, the book series was winding down. The last two of McDonald’s nine Fletch novels—Fletch Won and Fletch, Too—were published in 1985 and 1986, respectively, and McDonald was on auto-pilot by then. Those books actually occur first in chronological order (Won and Too, get it?), but they add little to Fletch’s backstory and consist almost entirely of dialogue. Though ostensibly set in the Southern California of the first novel, they seem to take place in Anytown, USA, since McDonald makes no effort to create a sense of place. (McDonald rebooted the series in the 1990s with Son of Fletch and Fletch Reflected, but these focus on Fletch’s illegitimate son, Jack, and aren’t generally regarded as canonical.)

Unfortunately, most of what made the first seven Fletch books such a pop-fiction phenomenon in the 1970s and early ’80s is missing from the film adaptations. For a start, the Fletch who made his literary debut in 1974 is in his 20s. He claims to be 29, but throughout the first novel, several characters insist that he looks younger. He seems to be about 25 but lies about his age in an attempt to be taken more seriously. Chevy Chase was born in 1943, and would have been a good choice to play Fletch in the 1970s, but by 1985, he was 42 years old (although he could pass for a man in his early 30s).

A bigger problem is that the filmmakers turned Fletch into Chase rather than vice versa. This was an understandable choice since Chase was then a hugely popular film star and original cast member of Saturday Night Live, whose talent for physical comedy and pratfalls had made the clumsy goofball his signature role. In his memoir, Which Lie Did I Tell?, screenwriter William Goldman recalls being hired to write the script for Memoirs of an Invisible Man in 1986, when Ivan Reitman was slated to direct and Chase was to star. By the time the film went into production several years later, both Reitman and Goldman had been replaced. Goldman noted that his script didn’t attempt to give the main character much depth because, “Bright as Chase was, he had not gotten famous playing drunks or scientists or death row convicts, he had become so playing a goof who had trouble with stairs.” And so, in the 1985 film, Fletch became a bit of a buffoon. Audiences didn’t seem to mind, but he bore little relation to McDonald’s creation.

In the book, I.M. Fletcher is an investigative reporter for a Southern California newspaper called the News-Tribune. For weeks, he has been living on a secluded stretch of beach populated by drug addicts and their mysterious dealer, Fat Sam. Crime writers who set their novels in Southern California often gave fictional names to real cities. Thus, Raymond Chandler’s detective Philip Marlowe operated in Bay City (recognizable as Santa Monica) and Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer operated in Santa Teresa (Santa Barbara). In an apparent effort to mimic this tradition, Gregory McDonald doesn’t identify Fletch’s home turf as Los Angeles, and refers to places such as The Beach and The Hills as if they are actual towns. The millionaire Alan Stanwyk who hires Fletch to kill him is said to live in The Hills (most likely Beverly Hills). By never referring to LA itself but instead referring only to various smaller, fictionalized cities within the county, McDonald is able to give his novel a small-town feel.

Fletch is described as being “as skinny as an alley cat,” and he has a gift for unobtrusively blending into crowds, frequently under a false name. McDonald’s Fletch employs pseudonyms that are designed to be forgotten—they almost always begin with John and end with a last name so unpronounceable that others don’t even bother trying to remember it: Utrelamensky, Yahmenaraleski, Zalumarinero, and so forth. When asked his occupation, he gives what he deems to be an equally forgettable response—“insurance,” “furniture,”—and when asked his hometown, he says “Butte, Montana.” No one, McDonald explains, “cared to inquire too deeply into either the furniture business or Butte, Montana. He believed himself absolutely unmemorable.” And although he fought in Vietnam and won a Bronze Star for bravery, when asked about his military service, Fletch always says he served in the Aleutians, an island chain in Alaska, because “no one cared about the Aleutians.”

When Gregory McDonald died in 2008, the New York Times obituary noted that, “Despite his acclaim, Mr. McDonald shunned the limelight. On airplanes, trapped next to seatmates who asked what he did, he would reply that he was in the insurance business. That preempted further interrogation.” Fletch, like his creator, doesn’t like to be noticed. But as portrayed by Chevy Chase, he seems to go out of his way to draw attention to himself. When asked his name, he’ll often give the name of someone famous, such as Ted Nugent, and he frequently wears elaborate disguises. Sneaking around a hospital dressed as a doctor, he keeps bumbling his name and dropping his clipboard, so he doesn’t escape attention, he attracts it. At the end of the film, he hands his boss an expense account that includes receipts for disguises like a gorilla suit and a nun’s habit.

The showy comic performance limns a character who is the exact opposite of the Fletch in McDonald’s novel. In the film’s sequel, 1989’s Fletch Lives, Chase mugs even harder, going the full Jerry Lewis. When first we see him, he is dressed in a French maid’s outfit, complete with blonde wig and fake breasts, in order to eavesdrop on a meeting of Greek-American mobsters, and an elderly letch follows him into the women’s bathroom to pinch his ass. Later we’ll see him dressed as a Ku Klux Klansman, Civil War General Robert E. Lee, and an evangelical preacher of color. As for his aliases, he uses Billy Jean King, Elmer Gantry, Bobby Lee Schwartz, and Ed Harley (while trying to pass himself off as the owner of the Harley Davidson Company to impress a violent motorcycle gang). Needless to say, none of this came from any of McDonald’s novels. The sequel’s script, by Leon Capetanos, is “original” in Hollywood-speak—meaning it isn’t an adaptation of one of McDonald’s novels—but there is very little originality in it.

Chase’s performance isn’t even Hollywood’s biggest betrayal of McDonald’s book—the whole character is reconceived. Chevy Chase’s Fletch may be a deadbeat divorcee who owes alimony to his two ex-wives and casually ogles women, but for the most part, he doesn’t cross any major ethical or legal lines. The same cannot be said for McDonald’s Fletch, who frequently behaves like a scumbag. Inexplicably, his two ex-wives remain fond of him and hope to reconcile with him someday, even though one of them divorced him after he threw her beloved cat out of their seventh-floor apartment window. Not only does he owe them both money, he takes a perverse pleasure in tormenting them. But this kind of spiteful misbehavior pales in comparison with the exploitative relationship he develops with a vulnerable young drug addict named Bobbi, who is written out of Ritchie’s film entirely.

When Fletch was published, Nixon’s war on drugs was raging and young people across the country were still heeding Timothy Leary’s advice to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” This dynamic helped widen the generation gap between boomers and their elders (back then, the media recognized only two generations—the old and the young). McDonald was 37 in 1974, neither exactly young nor old, which meant he didn’t have to choose a side in the culture war. Although the junkies at The Beach and their supplier Fat Sam are all portrayed sympathetically, McDonald doesn’t minimize the horrors of the needle and the damage done. Michael Ritchie’s film, on the other hand, is a light comic farce for the Reagan era, and he evidently didn’t wish to darken the mood by exploring the ugly side of addiction, so the drug dealing we see in the film appears to be largely victimless.

Bobbi’s full name is Roberta Sanders, but we don’t learn that until the end of the novel when McDonald reproduces her obituary. Fletch rents a shack on The Beach and goes out of his way to make Bobbi’s acquaintance. We learn that she has run away to Southern California from her home in Illinois, probably hoping to become a Hollywood starlet or, failing that, a rock-n-roll groupie. Instead, she ends up on The Beach hooked on heroin. She knows every junkie there, so Fletch invites her to live with him so he can ply her for information. But Bobbi doesn’t know that Fletch is an investigative reporter. She thinks he’s a 26-year-old fellow user, and fairly quickly, their relationship becomes sexual.

Here’s how Fletch describes her to his editor, Clara Snow (in the films, his editors are men): “Bobbi is as cute as a button, only sexier. She is fifteen, blond, with a beautiful, compact little body.” Snow asks him, “Aren’t you afraid of the law, Fletcher? A fifteen-year-old?” To which he responds, “If there is no one to complain for a kid, the law don’t give a shit.” Later, in a different context, he blithely remarks, “[A]s Pappy used to say about violating virgins, ‘Son, if you’re not the first, someone else will be.’” Although Bobbi is an addict who turns tricks with random strangers to pay for her habit, Fletch makes no effort to help her because he needs her as a source for his story.

The most moving exchange in the book takes place between Fletch and Bobbi at bedtime:

Still sitting, he lifted off his T-shirt. When he stood up to take off his pants and turn off the light, she got into the bedroll. He joined her.

She said, “Are you really twenty-six?”

“Yes,” he lied.

“I’ll never be twenty-six, will I?”

“I guess not.”

“How do I feel about that?” she asked.

“I don’t know.”

She said, “Neither do I.”

Bobbi is so young and so lost that she has to ask Fletch how she feels about things. A few days later, her prediction is fulfilled:

When Fletch woke at a quarter to three Monday morning, he found Bobbi lying in the sleeping bag beside him. He had not heard or felt her come in. It took him a moment to realize she was dead.

The back of his scalp tingling, he scrambled out of the sleeping bag.

As he knelt in the moonlight beside her, his scream choked with horror.

Her eyes appeared to have receded entirely into her head. Her left arm was puffy at the elbow and shoulder. She showed no vital signs.

He guessed she had overdosed.

He spent until dawn ridding the room of every sign of her.

Fletch buries Bobbi’s body in a secret location on The Beach. Days later, he’ll place an anonymous call to the police as part of a plan to implicate a corrupt police chief in her death. McDonald understands that in a capitalist society, the law of supply-and-demand makes the illegal-drug trade so profitable that even some of those paid to fight it don’t want to see it eradicated. As the source of the tainted heroin Fat Sam has been peddling, the cop is indeed culpable in the spate of overdose deaths ravaging the community. But Fletch’s callous indifference to Bobbi’s wellbeing makes him at least as responsible—a transgression for which he pays no price. At the end of the novel, Fletch flies to Rio de Janeiro with three million dollars packed into two suitcases that belonged to the late Alan Stanwyk. He didn’t murder Stanwyk, but the money he has stolen rightly belongs to Stanwyk’s widow and child. Fletch doesn’t care—he’s happy to take the money and run.

Fletch has more in common with 21st-century TV anti-heroes like Tony Soprano, Dexter Morgan, Barry Berkman, Walter White, Omar Little, Logan Roy, and Don Draper than he does with Chase’s incarnation. Now is the perfect time for Hollywood to give us an I.M. Fletcher as Gregory McDonald first imagined him: cruel, selfish, crooked, abusive, and amoral, but a gifted investigative reporter when he chooses to be. Still, that would have required a period piece. Fletch’s original milieu—the era of Vietnam, Chappaquiddick, Watergate, gonzo journalism, heavy drug use, government wiretaps, fake plumbers, unlawful CIA operations, “Never trust anyone over thirty,” etc.—isn’t just incidental to the books, it infuses nearly every aspect of them. It was an era when ordinary Americans began questioning institutions that had long been sacrosanct.

Confess, Fletch, the second book in the series, is an attack on American expertise, specifically in the crooked East Coast art world, and Greg Mottola’s new adaptation is a lot better than either of its predecessors. Not only is Jon Hamm a better actor than Chase, he’s also a better comic actor. He doesn’t need to fall down a flight of stairs or slap on a silly wig to make an audience laugh, and the film is surprisingly faithful to McDonald’s novel. Though set in contemporary America, the film’s plot plays out like a 1970s comic whodunit. Smart phones, GPS systems, laptops, and other 21st-century accoutrements play only a small role in the unraveling of the central mystery, and many of the film’s plot twists rely on old-school props—fireworks, paint cans, a rowboat. Hamm’s Fletch doesn’t wear any silly disguises, and the fake names he gives are so unmemorable that even he forgets them, sometimes inconveniently.

About the only nod to the Chevy Chase films is Fletch’s omnipresent Los Angeles Lakers hat (something never mentioned in the books). Hamm wears it in nearly every scene, but in this film, unlike the earlier two, the hat actually plays an important role in the plot. Of course, Jon Hamm is 51 years old (although, like Chase, he can pass for a man 10 years younger) and he’s certainly not “skinny as an alley cat.” No longer the walking Brooks Brothers advertisement he was during his Mad Men days, Hamm’s dad bod suits this updated version of Fletch, who has apparently sired a few children and is fluent in such contemporary parenting tropes as “the Ferber method” of sleep training. This is all very entertaining, but it’s light years away from the Fletch of the books, a reprehensible cad whose preferred method of putting a child to sleep is to get her high and then have sex with her.

In the final scene of Mottola’s film, a character played by John Slattery (who played Hamm’s boss in Mad Men, and plays his former boss here) asks Fletch to investigate ruthless octogenarian media mogul Walter March, who has just booted his son from the head of his media empire. This is a teasing reference to 1978’s Fletch’s Fortune, the third book in the series, in which Fletch is coerced by two men identifying themselves as CIA agents into bugging a gathering of elite American journalists they want to blackmail. When March is found murdered, every journalist at the gathering is a suspect, but McDonald again uses his story to disparage elites and their vaunted expertise. At one point, Fletch explains, “Experts are the sources of opinions. People are the sources of facts.”

Although many Americans now seem to hold traditions, institutions, and experts in contempt, the post-Watergate era was different. Traditional establishment journalists had attained cult hero status after the Vietnam war proved to be just as unwinnable as the Pentagon Papers had suggested it would be, and after Nixon had been forced to resign due, in large part, to aggressive reporting of his transgressions. Crusading investigative reporters like Fletch, regardless of their personal failings, were still admired by large numbers of ordinary people.

Now, however, America has so many media outlets and so many “journalists” that few people still believe in the idea of a non-partisan traditional press. Today, one man’s crusading investigative reporter is another man’s Democratic Party propagandist. Despite being a good journalist, Fletch would quickly be cancelled today, if not for having had sex with a 15-year-old drug addict, then for throwing a house-cat out of a seventh-story window. In order to give us a Fletch that isn’t sanitized, Hollywood would need to situate him back in his natural habitat. He really only makes sense as a baby boomer back in the 1970s.

Mottola’s coda indicates that Miramax is hoping his film will be the first in a profitable new franchise. I hope so too, but my hopes aren’t high. Only three other people were in attendance at the noon showing I saw the day it opened, and all of them gray-haired old boomer men like me. That’s not a demographic that generally supports successful contemporary film franchises. Perhaps if Mottola and Miramax had set the film back in the 1970s and hired some young heartthrob to play a more faithfully morally ambiguous version of Fletch, things might have been different. Someone like Miles Teller might have breathed new life into Fletch. As it is, the character seems to be running on fumes.