Politics

Israel’s Perilous Moment, Then and Now

Herf tells the complicated and often surprising story of the internal political struggles in Western capitals, as well as in the halls of the United Nations, that erupted at the end of the Second World War.

A review of Israel’s Moment: International Support for and Opposition to Establishing the Jewish State, 1945–1949 by Jeffrey Herf, Cambridge University Press, 500 pages (April 2022)

On November 29th, Israel will commemorate the 75th anniversary of the UN resolution dividing British mandatory Palestine into two independent states, one Jewish and one Arab. Next May, Israelis will celebrate the 75th anniversary of their nation’s Declaration of Independence. Yet these jubilee events will be marred by the reality that the Jewish state’s most determined enemies have never accepted the UN partition plan, otherwise known as the “two state solution” for resolving the conflict. In Ramallah on the West Bank and on Israel’s Northern and Southern borders, the tattered banner of Palestinian rejectionism still flies. That also means there is no end in sight to the murderous terrorist attacks against civilians in the heart of Israel.

The Palestinian narrative of the Nakba (an Arabic word meaning “catastrophe” or “disaster”) has acted as an accelerant on this fire. It depicts the UN partition resolution as a Western imperialist plot, backed by powerful Jewish financial interests, which then led to the dispossession and expulsion of the land’s indigenous people, and this account remains at the heart of the school curriculum taught at UN-administered Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza. Palestinian leaders of all stripes continue to insist that the only recompense for this historically unprecedented crime is to grant millions of so-called refugees the “right of return” to their original homes in Israel. In other words, the Nakba also implies the end of Israel as a Jewish state.

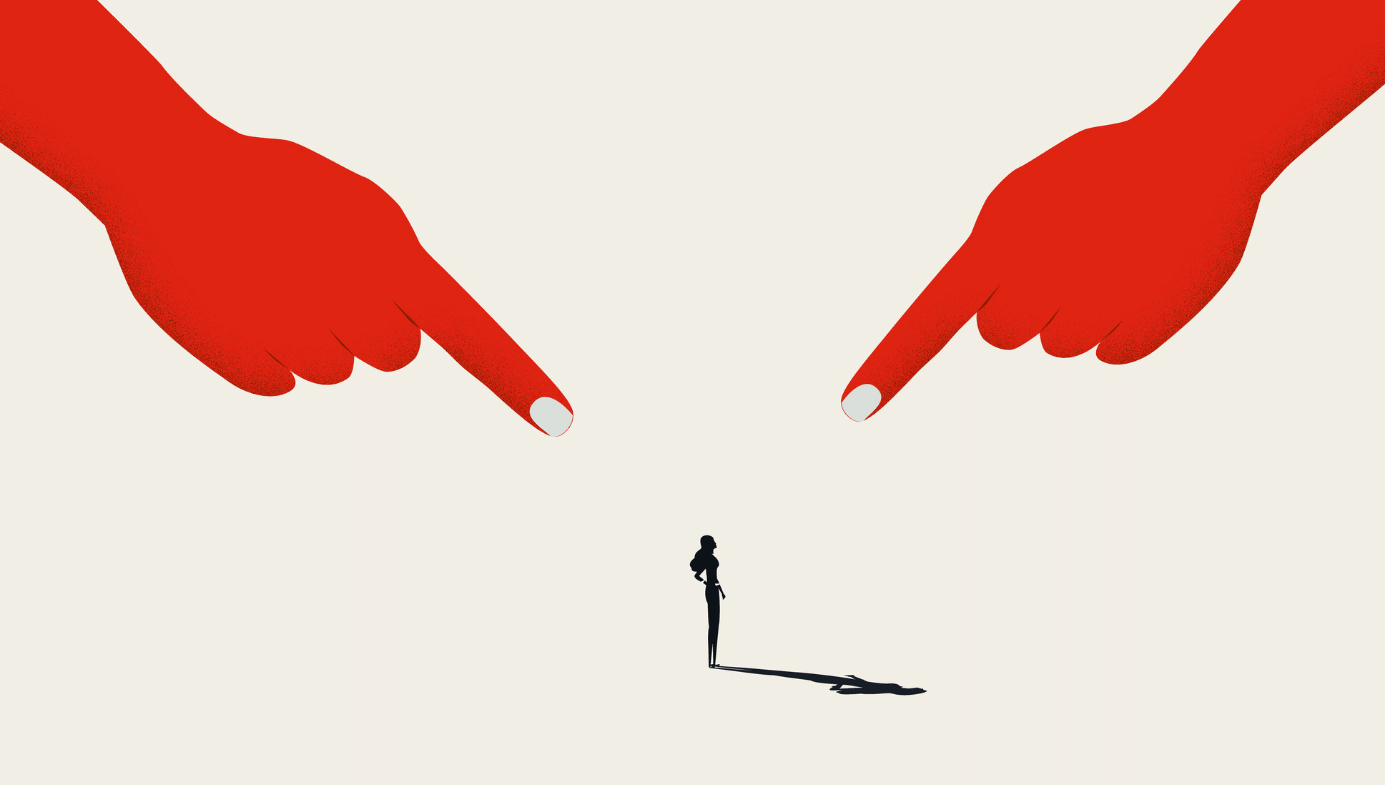

Despite its absurd historical revisionism and political impracticality, the Nakba narrative has managed to capture the imagination of much of the international Left and become a vector for antisemitism. At elite campuses across America, “progressive” students now routinely chant the slogan “Palestine from the River to the Sea” and equate support for Israel with racism.

This is the grim present-day background that makes Jeffrey Herf’s new book, Israel’s Moment, so timely and essential. The author is a distinguished historian of modern Germany whose previous work has focused on the affinities between the Nazis’ revolutionary antisemitism and modern Islamist ideologies propagated by groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas, al-Qaeda and the theocratic regime in Iran—a connection largely ignored in Middle East scholarship in the West.

In an earlier volume, Nazi Propaganda in the Arab World (2010), Herf relied on newly released German archival material to reveal startling new details about the wartime collaboration between the Nazi regime and Haj Amin al-Husseini, the preeminent leader of the Palestinian Arabs in the 1920s and ’30s. In 1921, the British mandatory government anointed Husseini as Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, charged with overseeing the city’s Islamic holy places. In the 1930s, the Mufti contemplated an alliance with the Nazis and sent Palestinian youth delegations to the Führer’s Nuremberg rallies.

After leading the violent Arab revolt against British forces in Palestine, Husseini escaped to Nazi Germany in 1940. In wartime Berlin, he helped organize the Nazi propaganda broadcasts transmitted across the Arab world. At an early audience with the Führer, he was informed about plans for the Final Solution and declared himself impressed. He then founded the Islamic Institute and issued a canonical statement emphasizing the symbiosis between Nazism and Islam, rooted in the Koranic prescription that “the most hostile people are the Jews.”

The Mufti also did some traveling on behalf of his wartime hosts. In Yugoslavia, he helped Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler establish a Waffen SS division for Bosnian Muslims, and became one of the brains behind German espionage operations in the Arab world. Had Rommel not been stopped at El Alamein, the Nazis might have conquered Palestine and the Mufti would likely have supervised the physical eradication of the Jewish community there.

Now, in Israel’s Moment, Herf tells the complicated and often surprising story of the internal political struggles in Western capitals, as well as in the halls of the United Nations, that erupted over the “Palestine question” after the end of the war. Delving deeply into American and French archival material, Herf challenges much of the conventional wisdom about how an independent Jewish state emerged in Palestine in 1948. Among its many benefits, Herf’s book exposes the big lie at the heart of the Nakba narrative—that Israel was created as a Western imperialist or colonialist outpost:

Contrary to four decades of Soviet, Arab state, Islamist and Palestinian nationalist propaganda, Zionism was not a product or tool of British or American imperialism. ... From 1945 to 1949 the Zionists had four primary foes: the Atlee-Bevin Labour government in London; former Nazi collaborators leading the Arab Higher Committee; the reactionary Arab regimes of the time and their allies in British, American and European oil corporations; and the national security establishment of the United States.

Herf also shows that the most passionate political support for Jewish statehood “came overwhelmingly from American liberals and left liberals, French socialists and between 1947 and 1949 from communists in France and the Soviet bloc, especially in Czechoslovakia.”

Herf begins his book by returning to Haj Amin al-Husseini’s nefarious activities during the war. These are important because, after the Mufti was captured by French military forces in 1945, the debates among the victorious Western allies about what to do with him turned out to be a prelude to the internal political struggles in those countries over the creation of the Jewish State.

American progressives and leftists who later pushed for Israel’s independence first came together to launch a public campaign to bring the Mufti to justice for his collaboration with the Nazis and for possible war crimes. But Husseini was shielded from prosecution by high-level government officials in the US and France who were determined to protect Western influence in the Arab world. In Washington, the sudden concern for the Mufti’s safety came from the same anti-Zionist faction within the Truman administration that later tried to block the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

After capturing Husseini in May 1945, the French government placed him under “house arrest” in a villa outside Paris. The Yugoslav government then requested that the Mufti be extradited to face trial for the war crimes he committed in the Balkans. French Foreign Ministry documents unearthed by Herf explain why this was never going to happen. A diplomatic memo put the matter quite directly: If the French government complied with the extradition request from Yugoslavia, or indeed from any other allied government, “we would unleash a new wave of hostility against us in all the Arab countries, and would also deprive ourselves of the interesting and fruitful contacts that the Mufti maintains with important figures from the Arab world.”

In June 1946, French security forces guarding the house where Husseini was detained conveniently left the door open and he “escaped” to Egypt. The Mufti was granted asylum by King Farouk and received a rapturous reception upon his return. In Cairo, he was greeted as a conquering hero by the founder of the islamofascist Muslim Brotherhood, Hassan al-Banna. The Mufti, al-Banna declared, was a great leader who “challenged an empire and fought Zionism with the help of Hitler and Germany. Germany and Hitler are gone, but Amin al-Husseini will continue the struggle.”

Within months, Husseini was reinstated as Chairman of the Arab Higher Committee, officially recognized in international forums as representing the Palestinian Arabs. After the passage of the UN partition resolution in November 1947, Al-Banna and Husseini combined forces and sent thousands of fighters into Palestine to begin the war against the Yishuv (the organized Jewish community in British mandatory Palestine) with the intent of aborting the Jewish state.

Summing up this sorry chapter in postwar Western diplomacy, Herf writes that the refusal of the Allies to hold Husseini accountable for his crimes “made it more likely that the Mufti and his associates would return to the political stage and at the international stage at the UN, oppose any compromise with the Jews, start the war against the Jews in November 1947, urge the Arab states to invade the new state of Israel in 1948 and stimulate hatred of the US and the western democracies.”

Other historians of this period (most notably Allis and Ronald Radosh in their 2009 book, A Safe Haven: Harry S. Truman and the Founding of Israel) have recounted President Truman’s steadfastness in championing statehood for the Jews, even against powerful internal opposition. To this history, Herf adds the most detailed account yet of just what Truman was up against from within his own administration. It is not an uplifting story.

High-level officials at the State Department, the CIA, and the Pentagon formed an informal anti-Zionist caucus that sought to undermine the president’s announced policies and block the emergence of an independent Jewish state. All too often, they succeeded in damaging Israel during its struggle for survival. The caucus first tried to stop implementation of the UN partition plan, even after the president had officially endorsed it. As a State Department memo put it in January 1948: “Our vital interests in those areas [the Arab Middle East] will continue to be adversely affected to the extent that we continue to support partition.” State Department officials urged the administration to cooperate with Great Britain in intercepting the ships carrying Jewish Holocaust survivors to Palestine.

The anti-Zionist caucus successfully pushed for a US arms embargo during the Palestine conflict which ended up hurting only Israel. That’s because the Jordanian Arab Legion, the most effective fighting force among the six invading Arab armies, was fully armed and led by British military forces. The military balance was restored only when Czechoslovakia agreed to send advanced military equipment to Israel. The anti-Zionist US officials were convinced the Jewish state couldn’t survive a war against the Arab armies, but when the Jews actually began winning, they threw their support behind UN mediator Folke Bernadotte’s proposal to take the Negev region away from Israel and give it to the Arabs.

The unofficial leader of this opposition faction was George F. Kennan, director of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff. During his long career as a government foreign policy expert, Kennan managed to exemplify the best and worst tendencies of the existing foreign policy establishment. While serving as the number two US embassy official in Moscow during World War II, he wrote the famous “long telegram” to his superiors in Washington predicting that the Stalin regime would pursue an aggressive and expansionist policy in Europe and that it could only be “contained” through active US countermeasures. Rewarded for his prescient analysis of Soviet behavior, Kennan was brought home by the Truman administration and installed as director of the State Department’s newly established Policy Planning Staff.

As Herf shows, it was partly because of the exigencies of fighting the Cold War that Kennan and many of his colleagues misread the postwar politics of the Middle East. The foreign policy establishment was caught off guard when the Soviet Union suddenly reversed course after two decades of ideological anti-Zionism and championed partition at the United Nations. That policy switch reinforced Kennan’s belief that a Jewish state in the Middle East would be harmful to America’s strategic interests in the Cold War.

Kennan and other US officials even came to believe the fantastic rumor (more accurately, the conspiracy theory) that the Soviets were sending thousands of communist agents into the new state in order to help establish a bridgehead for its own imperial ambitions in the Middle East. As a result, the FBI began investigating Jewish American volunteers serving in Israel’s defense forces for possible communist connections.

Incredibly, the New York Times, not especially friendly to Zionism then or now, fell for this canard and ran a front-page story headlined: “Red ‘Fifth Column’ for Palestine Feared as Ships Near Holy Land.” This was Cold War McCarthyism even before Joe McCarthy (though when Senator McCarthy did appear on the scene, he targeted the same State Department for harboring communists and spies).

Herf provides excerpts from a series of headshaking memos by Kennan and his staff who argued that support for a Jewish State would make American containment of Soviet communism more difficult. One document warned that “any assistance the US might give to the enforcement of partition would result in deep seated antagonism for the US in many sections of the Moslem world over many years.” Another referred to “the adverse effect on Aramco and Tapien of the Pro Zionist Policy of the United States Government. All Arabs resent the actions of the present United States administration as unfriendly to them.” Another high-ranking State Department official, Samuel K.C. Kopper, circulated his analysis that the partition plan was “unworkable” and the administration “should abandon its support for partition.”

It’s hard to imagine an operation more brazen, elitist, and anti-democratic than the Kennan group’s effort to reverse an American President’s carefully considered and publicly announced policies. Thankfully, the administration’s anti-Zionists were unable to achieve their goal of scuttling partition and sending the Palestine issue back to the United Nations. Despite intense pressure from almost the entire national security establishment, Truman held his ground and recognized the new state of Israel within hours of its formal declaration of independence.

Nevertheless, the Kennan faction managed to undermine the new state in significant ways, while encouraging the Arabs with false hopes that they could actually win their war against the Jews. Israel’s first government wasn’t fooled by the hoopla over US recognition. Herf reports that, when the war for independence was won, Prime Minister Ben Gurion told US Ambassador James McDonald that “if the Jews had been dependent on the United States for survival in the 1947–1948 war they would have been exterminated.”

If George Kennan is the main villain of Jeffrey Herf’s book, the heroes are a determined group of journalists who spoke out about the plight of Jewish Holocaust survivors blocked from entering Palestine. These writers then championed the Zionist project in several daily newspapers and in the pages of highbrow liberal magazines such as the Nation and the New Republic. Herf spends about 50 pages telling their story—arguably the most honorable chapter for liberal and leftwing American journalism in the 20th century.

The brightest stars in this constellation of pro-Zionist journalists were Freda Kirchwey, longtime editor of the Nation, and the legendary reporter I.F. Stone. Stone covered the Jewish refugee crisis in Europe after the Holocaust and then Israel’s war of independence for PM, the most influential progressive newspaper of the 1940s. Kirchwey, meanwhile, turned her venerable progressive weekly (founded in 1865) into a journalistic battle-tank fighting for the Jewish people after the Holocaust. She published dozens of major essays by a wide array of well-known writers and public officials supporting Zionist aspirations, including several by Stone. The series kicked off in 1945 with a fiery article by Senator Robert Wagner (a Democrat representing New York) denouncing Britain’s anti-Zionist policies and calling Jewish Palestine “the most successful pioneering effort in human history.”

Before the UN General Assembly was scheduled to vote on the partition resolution, the Nation submitted a lengthy report to all the voting member states titled, “The Arab Higher Committee: Its Origins, Personnel, and Purposes.” Supervised by Kirchwey, the report urged UN members to vote for partition and concluded by calling Husseini’s Arab Higher Committee “an almost exact equivalent in Middle Eastern terms, of the cabal that ruled Hitler’s Germany.” The theme that the Palestinians were led by Nazi collaborators was also stressed in many of the dispatches and essays that I.F. Stone wrote for PM and the Nation.

In his survey of the pro-Zionist journalism of the time, Herf devotes a lot of attention to Stone’s reports of the voyage he took aboard an “illegal” ship carrying Holocaust survivors to Palestine and the ship’s attempts to dodge the British Naval blockade. Stone’s personal dispatches were a spectacular example of courageous journalism, and the widely praised book he wrote about his experience, Underground to Palestine, had a big impact on the American debate over the Jewish State.

It’s too bad that Herf doesn’t discuss Stone’s next book, This is Israel, published in late 1948 by a major US publishing house. In my view, this second volume was even more important to the pro-Israel cause than his first. In Underground to Palestine, Stone expressed a preference for a bi-national state in Palestine that would satisfy the aspirations of both Jews and Arabs. But by the time Stone returned to Israel in May 1948, just as the Jewish state was about to be invaded by the Arab armies, he realized that no compromise was possible and that Israel had to win the war or die.

This Is Israel opens with a glowing forward written by Bartley Crum, publisher of PM. Crum writes that through Stone’s account of the Jews’ struggle for independence, “we Americans can warm ourselves in the glory of a free people who made a two-thousand-year dream come true in their own free land.” Indeed, Stone’s text reads like a heroic epic intended to generate support for the Israeli war effort. He calls the young state a “tiny bridgehead” of 650,000 faced by 30 million Arabs. “Arab leaders made no secret of their intentions,” Stone writes, and then quotes the head of the Arab League, Abdul Rahman Azzam, as follows: “This war will be a war of extermination and a momentous massacre which will be spoken of like the Mongol massacres and the Crusades.”

Significantly, Stone blames Haj Amin al-Husseini and the Arab Higher Committee for creating the Palestinian refugee crisis. The Palestinian leaders reminded him of the fascists he had fought with his pen since the Spanish Civil War, and he ticks off the names of Nazi collaborators leading Palestinian military units attacking Jewish settlements after passage of the UN partition resolution. “German Nazis, Polish reactionaries, Yugoslav Chetniks, and Bosnian Moslems flocked [into Palestine] for the war against the Jews,” Stone writes.

Though it’s not part of Jeffrey Herf’s book, I found myself thinking about the historical ironies that led the major political players during the struggles over the creation of Israel to eventually switch sides. Perhaps the most consequential example of this turnabout occurred when the Stalin regime reverted to its historical anti-Zionism, even criminalizing Zionist activism. Alarmed by the euphoric reception Golda Meir received from Russian Jews during her ambassadorial visit to the USSR in 1948, Stalin began to obsess about the threat posed to the Soviet Union by Jewish disloyalty. As a result, the Soviets unleashed the big lie that Israel was actually a creation of Western imperialism—propaganda that the Arab world was happy to embrace.

Six years later, the British and French governments collaborated with Israel in a joint military action against Egypt to obtain free passage through the Suez Canal, an operation aborted following pressure from the Soviet Union, the UN, and the US. But from the Kennedy and Johnson administrations onwards, successive American governments began to cast a friendlier eye on Israel as a potential military ally in the Middle East.

The most radical ideological change of direction regarding Israel occurred within the ranks of American journalism. By the late 1960s, the Nation had turned into a hot bed of anti-Israel commentary, as had many other leftist and liberal publications. In an essay for the New York Review of Books after Israel’s victory in the Six Day War, I.F. Stone, by now an icon of American journalism, castigated the Zionists for “moral myopia” and their lack of compassion for the Palestinians. Henceforth, most of the liberal media would dwell endlessly and disproportionately on Israel’s imperfections.

None dared recall that, only a few years before, Stone and the editor of the Nation had forensically documented the collaboration between the Palestinian Arab leadership and the Nazis, nor that these left-wing journalists had once argued passionately that the birth of Israel was one of the great moral triumphs of the 20th century. It is to Jeffrey Herf’s credit as an historian and scholar that he has provided this important reminder of who actually defended and opposed international justice for the Jewish people 75 years ago.